subsecref \newrefsubsecname = \RSsectxt \RS@ifundefinedthmref \newrefthmname = theorem \RS@ifundefinedlemref \newreflemname = lemma \newrefthmname=Theorem ,Name=Theorem \newrefpropname=Proposition ,Name=Proposition \newrefdefname=Definition ,Name=Definition \newreflemname=Lemma ,Name=Lemma \newrefcorname=Corollary ,Name=Corollary \newrefasmname=Assumption ,Name=Assumption \newrefappname=Appendix ,Name=Appendix \newrefclaimname=Claim ,Name=Claim

Well-conditioned Primal-Dual Interior-point Method for Accurate Low-rank Semidefinite Programming††thanks: Financial support for this work was provided by NSF CAREER Award ECCS-2047462 and ONR Award N00014-24-1-2671.

Abstract

We describe how the low-rank structure in an SDP can be exploited to reduce the per-iteration cost of a convex primal-dual interior-point method down to time and memory, even at very high accuracies. A traditional difficulty is the dense Newton subproblem at each iteration, which becomes progressively ill-conditioned as progress is made towards the solution. Preconditioners have been proposed to improve conditioning, but these can be expensive to set up, and fundamentally become ineffective at high accuracies, as the preconditioner itself becomes increasingly ill-conditioned. Instead, we present a well-conditioned reformulation of the Newton subproblem that is cheap to set up, and whose condition number is guaranteed to remain bounded over all iterations of the interior-point method. In theory, applying an inner iterative method to the reformulation reduces the per-iteration cost of the outer interior-point method to time and memory. We also present a well-conditioned preconditioner that theoretically increases the outer per-iteration cost to time and memory, where is an upper-bound on the solution rank, but in practice greatly improves the convergence of the inner iterations.

1 Introduction

Given problem data and and , we seek to solve the standard-form semidefinite program (SDP)

| (1a) | ||||

| (1b) | ||||

| assuming that the primal problem (1a) admits a unique low-rank solution | ||||

| (1c) | ||||

| and that the dual problem (1b) admits a strictly complementary solution (not necessarily unique) | ||||

| (1d) | ||||

Here, denotes the space of real symmetric matrices with the inner product , and signifies that is positive semidefinite. We assume without loss of generality that the constraints represented by are linearly independent, meaning implies . This assumption restricts the number of constraints to . Both of these conditions are mild and are widely regarded as standard assumptions.

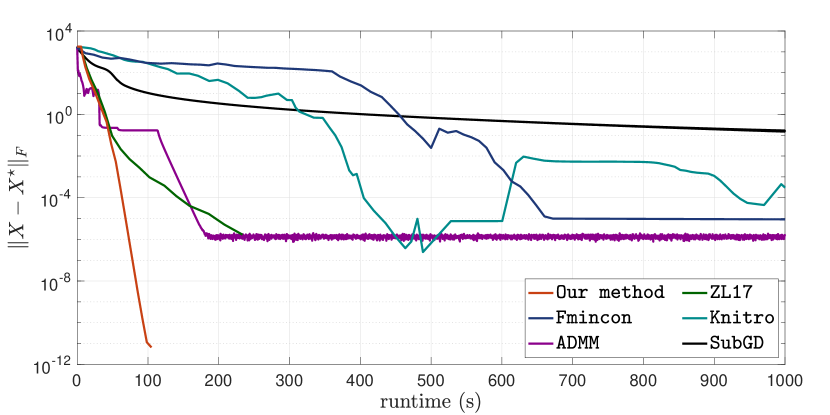

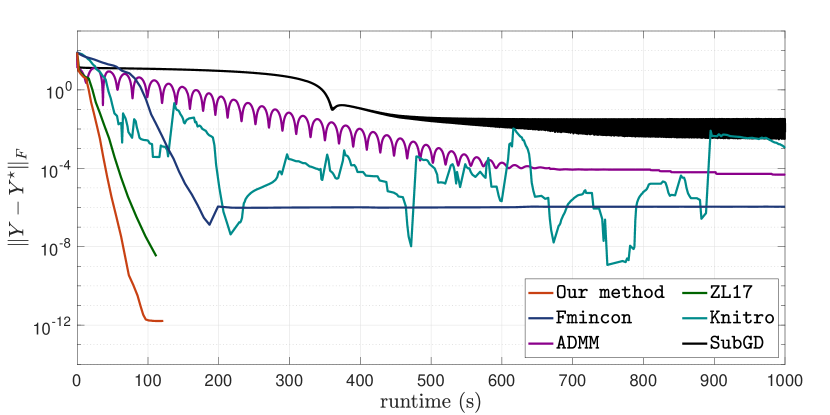

Currently, the low-rank SDP (1) is most commonly approached using the nonconvex Burer–Monteiro factorization [12], which is to factorize into an low-rank factor , where is a search rank parameter, and then to locally optimize over . While this can greatly reduce the number of optimization variables, from down to as low as , the loss of convexity can create significant convergence difficulties. A basic but fundamental issue is the possibility of failure by getting stuck at a spurious local minimum over the low-rank factor [11]. Even ignoring this potential failure mode, it can still take a second-order method like cubic regularization or a trust-region method up to iterations to reach second-order optimality over , where a primal-solution with duality gap can (hopefully) be extracted [11]. In practice, the Burer–Monteiro approach works well for some problems [10, 38, 20], but as shown in Fig. 1, can be slow and unreliable for other problems, particularly those with underlying nonsmoothness.

In this paper, we revisit classical primal-dual interior-point methods (IPMs), because they maintain the convexity of the SDP (1), and therefore enjoy simple and rapid global convergence to duality gap in iterations. IPMs are second-order methods that solve a sequence of logarithmic penalized SDPs of the form

while progressively decreasing the duality gap parameter after each iteration. Using an IPM, the cost of solving (1) is almost completely determined by the cost of solving the Newton subproblem at each iteration

| (2a) | |||

| (2b) | |||

| in which the scaling point and the residuals are iteration- and algorithm-dependent. In fact, using a short-step strategy (with fixed step-sizes) [36, Theorem 6.1], solving the SDP (1) to duality gap costs exactly the same as solving an instances of (2) to accuracy. By paying some small per-iteration overhead, long-step strategies (with adaptive step-sizes) can consistently reduce the iteration count down to 50-100 in practice [47, 42]. | |||

Instead, the traditional difficulty faced by IPMs is the high cost of accurately solving the Newton subproblem (2) at each iteration. This difficulty arises due to need to use a scaling point that is both dense and becomes increasing ill-conditioned with decreasing values of . Although our technique is more broadly applicable, we will focus this paper on the primal-dual Nesterov–Todd scaling [35, 36], which is computed from the current iterates as follows

| (2c) |

and appears in popular general-purpose IPM solvers like SeDuMi [41], SDPT3 [46], and MOSEK [34]. The ill-conditioning in makes it increasingly difficult to solve (2) to sufficiently high accuracy for the outer IPM to continue making progress. Therefore, most IPM solvers, like those listed above, solve (2) by directly forming and factorizing its Karush–Kuhn–Tucker equations. Unfortunately, the density of renders these equations dense, irrespective of any sparsity in the data and . For SDPs with constraints, the cost of solving (2) by the direct approach is time and memory, hence limiting to no more than about 200.

In this paper, we instead solve (2) using a preconditioned iterative approach, as a set of inner iterations within the outer IPM iterations. Our main contribution is to use the low-rank structure in (1) to provably reduce the cost of computing a numerically exact solution to (2) to time and memory, where is a search rank parameter as before, and is the machine precision. Critically, these complexity figures hold even for SDPs with constraints. This matches the per-iteration costs of second-order implementations of the Burer–Monteiro method, but we additionally retain the iteration bound enjoyed by classical IPMs. As we now explain, our main challenge is being able to maintain these complexity figures even at high accuracies, where becomes very small, and becomes extremely ill-conditioned.

1.1 Prior work: Spectral preconditioning

By taking advantage of fast matrix-vector products with the data , an iterative approach can reduce the cost of solving the Newton subproblem (2) to as low as time and memory. However, without an effective preconditioner, these improved complexity figures are limited to coarse accuracies of . The key issue is that the scaling point becomes ill-conditioned as . Iterating until the numerical floor yields a numerically exact solution to (2) that is indistinguishable from the true solution under finite precision, but the number of iterations to achieve this grows as . Truncating after a much smaller number of iterations yields an inexact solution to (2) that can slow the convergence of the outer IPM.

Toh and Kojima [45] proposed the first effective preconditioner for SDPs. Their critical insight is the empirical observation that the scaling point becomes ill-conditioned as only because its eigenvalues split into two well-conditioned clusters:

| (A0) |

Based on this insight, they formulated a spectral preconditioner that attempts to counteract the ill-conditioning between the two clusters, and demonstrated promising computational results. However, the empirical effectiveness was not rigorously guaranteed, and its expensive setup cost of time made its overall solution time comparable to a direct solution of (2), particularly for problems with constraints.

Inspired by the above, Zhang and Lavaei [53] proposed a spectral preconditioner that is much cheaper to set up, and also rigorously guarantees a high quality of preconditioning under the splitting assumption (A0). Their key idea is to rewrite the scaling point as the low-rank perturbation of a well-conditioned matrix, and then to approximate the well-conditioned part by the identity matrix

Indeed, it is easy to verify that the joint condition number between and is bounded under (A0) even as . Substituting into (2) reveals a low-rank perturbed problem that admits a closed-form solution via the Sherman–Morrison–Woodbury formula, which they proposed to use as a preconditioner. Assuming (A0) and the availability of fast matrix-vector products that we outline as (A3) below, they proved that their method computes a numerically exact solution in time and memory. This same preconditioning idea was later adopted in the solver Loraine [27].

In practice, however, the Zhang–Lavaei preconditioner loses its effectiveness for smaller values of , until abruptly failing at around . This is an inherent limitation of preconditioning in finite-precision arithmetic; to precondition a matrix with a diverging condition number , the preconditioner’s condition number must also diverge as . As approaches zero, it eventually becomes impossible to solve the preconditioner accurately enough for it to remain effective. This issue is further exacerbated by the use of the Sherman–Morrison–Woodbury formula, which is itself notorious for numerical instability.

Moreover, the effectiveness of both prior preconditioners critically hinges on the splitting assumption (A0), which lacks a rigorous justification. It was informally argued in [45, 44] that the assumpution holds under strict complementarity (1d) and the primal-dual nondegeneracy of Alizadeh, Haeberly, and Overton [2]. But primal-dual nondegeneracy is an excessively strong assumption, as it would require the number of constraints to be within the range of

In particular, it is not applicable to the diverse range of low-rank matrix recovery problems, like matrix sensing [37, 17], matrix completion [15], phase retrieval [18], that necessarily require measurements in order to uniquely recover an underlying rank- ground truth. It is also not applicable to problems with constraints, which as we explained above, are the most difficult SDPs to solve for a fixed value of .

1.2 This work: Well-conditioned reformulation and preconditioner

In this paper, we derive a well-conditioned reformulation of the Newton subproblem (2) that costs just time and memory to set up. In principle, as the reformulation is already well-conditioned by construction, it allows any iterative method to compute a numerically exact solution in iterations for all values of . In practice, the convergence rate can be substantially improved by the use of a well-conditioned preconditioner. Assuming (A0) and the fast matrix-vector products in (A3) below, we provably compute a numerically exact solution in time and memory. But unlike Zhang and Lavaei [53], our well-conditioned preconditioner maintains its full effectiveness even at extremely high accuracies like , hence fully addressing a critical weakness of this prior work.

Our main theoretical results are a tight upper bound on the condition number of the reformulation and the preconditioner (3.3), and a tight bound on the number of preconditioned iterations needed to solve (2) to accuracy (3.5). These rely on the same splitting assumption (A0) as prior work, which we show is implied by a strengthened version of strict complementarity (1d). In 3.1, we prove that (A0) holds if the primal-dual iterates used to compute the scaling point in (2) satisfy the following centering condition (the spectral norm is defined as the maximum singular value):

| (A1) |

In particular, the restrictive primal-dual nondegeneracy assumption adopted by prior work [45, 44] is completely unnecessary. By repeating the algebraic derivations in [30], it can be shown that (A1) holds under strict complementarity (1d) if the IPM maintains its primal-dual iterates within the “wide” neighborhood [48, 35, 6]. In turn, most IPMs that achieve an duality gap in iterations—including essentially all theoretical short-step methods [35, 36, 43] but also many practical methods like the popular solver SeDuMi [41]—do so by keeping their iterates within the neighborhood [42]. In Section 7.1, we experimentally verify for SDPs satisfying strict complementarity (1d) that SeDuMi [41] keeps its primal-dual iterates sufficiently centered to satisfy (A1).

Under (A1), which implies the splitting assumption (A0) adopted in prior work via 3.1, we prove that preconditioned iterations solve (2) to accuracy for all values of . In order for the reformulation and the preconditioner to remain well-conditioned, however, we require a strengthened version of the primal uniqueness assumption (1c). Concretely, we require the linear operator to be injective with respect to the tangent space of the manifold of rank- positive semidefinite matrices, evaluated at the unique primal solution :

| (A2) |

This is stronger than primal uniqueness because it is possible for a rank- primal solution to be unique with just constraints [2], but (A2) can hold only when the number of constraints is no less than the dimension of the tangent space

Fortunately, many rigorous proofs of primal uniqueness, such as for matrix sensing [37, 17], matrix completion [15], phase retrieval [18], actually work by establishing (A2). In problems where (A2) does not hold, it becomes possible for our reformulation and preconditioner to grow ill-conditioned in the limit . For these cases, the behavior of our method matches that of Zhang and Lavaei [53]; down to modest accuracies of , our preconditioned iterations will still rapidly converge to accuracy in iterations.

Our time complexity figures require the same fast matrix-vector products as previously adopted by Zhang and Lavaei [53] (and implicitly adopted by Toh and Kojima [45]). We assume, for and , that the two matrix-vector products

| (A3) |

can both be performed in time and storage. This is satisfied in problems with suitable sparsity and/or Kronecker structure. In Section 7.1, we rigorously prove that the robust matrix completion and sensor network localization problems satisfy (A3) due to suitable sparsity in the operator .

1.3 Related work

Our well-conditioned reformulation of the Newton subproblem (2) is inspired by Toh [44] and shares superficial similarities. Indeed, the relationship between our reformulation and the Zhang–Lavaei preconditioner [53] has an analogous relationship to Toh’s reformulation with respect to the Toh–Kojima preconditioner [45]. However, the actual methods are very different. First, Toh’s reformulation remains well-conditioned only under primal-dual nondegeneracy, which as we explained above, makes it inapplicable to most low-rank matrix recovery problems, as well as problems with constraints. Second, the effectiveness of Toh’s preconditioner is not rigorously guaranteed; due to its reliance on the PSQMR method, the Faber–Manteuffel Theorem [22] says that it is fundamentally impossible to prove convergence for the preconditioned iterative method. Third, our set-up cost of is much cheaper than Toh’s set-up cost of ; this parallels the reduction in set-up cost achieved by the Zhang–Lavaei preconditioner [53] over the Toh–Kojima preconditioner [45].

We mention another important line of work on the use of partial Cholesky preconditioners [7, 24, 4], which was extended to IPMs for SDPs in [5]. These preconditioners are based on the insight that a small number of ill-conditioned dimensions in the Newton subproblem (2) can be corrected by a low-rank partial Cholesky factorization of its underlying Schur complement. However, to the best of our knowledge, such preconditioners do not come with rigorous guarantees of an improvement.

Outside of SDPs, our reformulation is also inspired by the layered least-squares of Bobrovnikova and Vavasis [9]; indeed, our method can be viewed as the natural SDP generalization. However, an important distinction is that they apply MINRES directly to solve the indefinite reformulation, whereas we combine PCG with an indefinite preconditioner to dramatically improve the convergence rate. This idea of using PCG to solve indefinite equations with an indefinite preconditioner had first appeared in the scientific computing literature [29, 25, 39].

We mention that first-order methods have also been derived to exploit the low-rank structure of the SDP (1) without giving up the convexity [14, 51, 49]. These methods gain their efficiency by keeping all their iterates low-rank, and by performing convex updates on the low-rank iterates while maintaining them in low-rank factored form . While convex first-order methods cannot become stuck at a spurious local minimum, they still require iterations to converge to an -accurate solution of (1). In contrast, our proposed method achieves the same in just iterations, for an exponential factor improvement.

Finally, for low-rank SDPs with small treewidth sparsity, chordal conversion methods [23, 28] compute an accurate solution in guaranteed time and memory [54, 52]. Where the property holds, chordal conversion methods achieve state-of-the-art speed and reliability. Unfortunately, many real-world problems do not enjoy small treewidth sparsity [32]. For low-rank SDPs that are sparse but non-chordal, our proposed method can solve them in as little as time and memory.

Notations

Write as the sets of real matrices, real symmetric matrices, positive semidefinite matrices, and positive definite matrices, respectively. Write as the column-stacking vectorization, and as the Kronecker product satisfying . Write and as spectral norm and Frobenius norm, respectively. Let denote the basis for the set of vectorized real symmetric matrices . We define the symmetric vectorization of as

We note that for all . Like the identity matrix, we will frequently suppress the subscript if the dimensions can be inferred from context. Given , we define their symmetric Kronecker product as so that holds for all . (See also [2, 45, 44] for earlier references on the symmetric vectorization and Kronecker product.)

2 Background: Iterative solvers for symmetric indefinite equations

2.1 MINRES

Given a system of equations with a symmetric and right-hand side , we define the corresponding minimum residual (MINRES) iterations with respect to positive definite preconditioner , and initial point implicitly in terms of its Krylov optimality condition.

Definition 2.1 (Minimum residual).

Given and and , we define where

and and and .

The precise implementation details of MINRES are complicated, and can be found in the standard reference [26, Algorithm 4]. We only note that the method uses memory over all iterations, and that each iteration costs time plus the the matrix-vector product and the preconditioner linear solve . In exact arithmetic, MINRES terminates with the exact solution in iterations. With round-off noise, however, exact termination does not occur. Instead, the behavior of the iterates are better predicted by the following bound.

Proposition 2.2 (Symmetric indefinite).

Given and and , let Then, we have in at most

where .

2.2 PCG

Given a system of equations with a symmetric and right-hand side , we define the corresponding preconditioned conjugate gradient (PCG) iterations with respect to preconditioner not necessarily positive definite, and initial point explicitly in terms of its iterations.

Definition 2.3 (Preconditioned conjugate gradients).

Given and , we define where for

and and .

We can verify from 2.3 that the method uses memory over all iterations, and that each iteration costs time plus the the matrix-vector product and the preconditioner linear solve . The following is a classical iteration bound for when PCG is used to solve a symmetric positive definite system of equations with a positive definite preconditioner.

Proposition 2.4 (Symmetric positive definite).

Given and , let . Then, both holds in at most

where .

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, it was pointed out in several parallel works [29, 25, 39] that PCG can also be used to solve indefinite systems, with the help of an indefinite preconditioner. The proof of 2.5 follows immediately by substituting into 2.3.

Proposition 2.5 (Indefinite preconditioning).

Given and and and and , let

| (3a) | |||

| (3b) | |||

In exact arithmetic, we have and for all .

Proof.

Therefore, the indefinite preconditioned PCG (3a) is guaranteed to converge because it is mathematically equivalent to PCG on the underlying positive definite Schur complement system (3b). Nevertheless, (3a) is more preferable when the matrix is close to singular, because the two indefinite matrices in (3a) can remain well-conditioned even as . As the two Schur complements become increasingly ill-conditioned, the preconditioning effect in (3b) begins to fail, but the indefinite PCG in (3a) will maintain its rapid convergence as if perfectly conditioned.

3 Proposed method and summary of results

Given scaling point and residuals , our goal is to compute and in closed-form via the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker equations

| (Newt-) |

where , and then recover . We focus exclusively on achieving a small enough as to be considered numerically exact.

As mentioned in the introduction, the main difficulty is that the scaling point becomes progressively ill-conditioned as the accuracy parameter is taken . The following is a more precise statement of (A1).

Assumption 1.

There exist absolute constants and such that the iterates , where , satisfy

with respect to that satisfy and .

Under 1, the eigenvalues of split into a size- cluster that diverges as , and a size- cluster that converges to zero as . Therefore, its condition number scales as , and this causes the entire system to become ill-conditioned with a condition number like .

Lemma 3.1.

Proof.

Write and and , and let denote the matrix geometric mean operator of Ando [3]. Substituting the matrix arithmetic-mean geometric-mean [3, Corollary 2.1] inequalities and into yields

which we combine with and to obtain

The first row yields for , and and . We can select a fixed point and combine the second row to yield

which is valid for all . In particular, if we choose such that , then and . ∎

To derive a reformulation of (Newt-) that remains well-conditioned even as , our approach is to construct a low-rank plus well-conditioned decomposition of the scaling matrix

First, we choose a rank parameter , and then partition the orthonormal eigendecomposition of the scaling matrix into two parts

| (4a) | |||

| Then, we choose a threshold parameter and define | |||

| (4b) | |||

| (4c) | |||

| (4d) | |||

The statement below characterizes this decomposition.

Proposition 3.2 (Low-rank plus well-conditioned decomposition).

Proof.

We propose using an iterative Krylov subspace method to solve the following

| (5a) | |||

| and then recover a solution to (Newt-) via the following | |||

| (5b) | |||

Our main result is a theoretical guarantee that our specific choice of in (4) results in a bounded condition number in (5a), even as . Notably, the well-conditioning holds for any rank parameter ; this is important, because the exact value of is often not precisely known in practice. The following is a more precise version of (A2) stated in a scale-invariant form.

Assumption 2 (Tangent space injectivity).

Factor with . Then, there exists a condition number such that

Theorem 3.3 (Well-conditioning).

The most obvious way to use this result is to solve the well-conditioned indefinite system in (5a) using MINRES, and then use (5b) to recover a solution to (Newt-). In theory, this immediately allows us to complete an interior-point method iteration in time and memory.

Corollary 3.4.

Given , suppose that 1 and 2 hold with parameters . Select and , and define as in (4). Let

and recover and from (5b). Then, the residual condition (Newt-) is satisfied in at most

for all with a logarithmic dependence on . Moreover, suppose that and can be evaluated in at most time and storage for all and . Then, this algorithm can be implemented in time and storage.

In practice, while the condition number of the augmented matrix in (5a) does remain bounded as , it can grow to be very large, and MINRES can still require too many iterations to be effective. We propose an indefinite preconditioning algorithm. Below, recall that denotes the -th iterate generated by PCG when solving using preconditioner and starting from an initial .

Assumption 3 (Fast low-rank matrix-vector product).

For and , the two matrix-vector products and can both be performed in at most time and storage.

Corollary 3.5.

Given , suppose that 1 and 2 hold with parameters . Select and , and define as in (4). Let where , and let

where is chosen to satisfy , and recover and from (5b). Then, the residual condition (Newt-) is satisfied in at most

where and , with no dependence on . Under 3, this algorithm can be implemented with overall cost of time and storage.

As we explained in the discussion around 2.5, the significance of the indefinite preconditioned PCG in 3.5 is that both the indefinite matrix and the indefinite preconditioner are well-conditioned for all via 3.3. Therefore, the preconditioner will continue to work even with very small values of .

In practice, the iteration count predicted in 3.5 closely matches experimental observations. The rank parameter controls the tradeoff between the cost of the preconditioner and the reduction in iteration count. A larger value of leads to a montonously smaller and faster convergence, but also a cubically higher cost.

4 Proof of Well-Conditioning

Our proof of 3.3 is based on the following.

Lemma 4.1.

Suppose that . Then,

where .

Proof.

Block diagonal preconditioning with yields

Let and . We perform a block-triangular decomposition

where . Substituting and yields . The desired estimate follows from . ∎

Given that is already assumed to be well-conditioned, 4.1 says that the augmented matrix is well-conditioned if and only if the Schur complement is well-conditioned. 3.2 assures us that is always bounded as , so the difficulty of the proof is to show that also remains bounded.

In general, we do not know the true rank of the solution. If we choose , then both terms and will become singular in the limit , but their sum will nevertheless remain non-singular. To understand why this occurs, we need to partition the columns of into the dominant eigenvalues and the excess eigenvalues, as in

| (6) |

We emphasize that the partitioning is done purely for the sake of analysis. Our key insight is that the matrix inherents a similar partitioning.

Lemma 4.2 (Partioning of and ).

Given in (6), choose , let and . Define

Then, there exists permutation matrix so that where

and where

Proof.

Let without loss of generality. For any and , we verify that

where we have partitioned and appropriately. Next, we verify that

∎

Applying 4.2 allows us to further partition the Schur complement into blocks:

In the limit , the following two lemmas assert that the two diagonal blocks and will remain nonsingular. This is our key insight for why will also remain nonsingular.

Lemma 4.3 (Eigenvalue bounds on ).

Proof.

Lemma 4.4 (Tangent space injectivity).

Given , let and let to be its orthogonal complement, and define where and . Then, we have where

Proof.

Let . The characterization of where and in 3.2 yields

Step (a) follows from with . Step (b) is by substituting . ∎

In order to be able to accommodate small but nonzero values of , we will need to be able to perturb 4.4.

Lemma 4.5 (Injectivity perturbation).

Let have orthonormal columns. Then,

We will defer the proof of 4.5 in order to prove our main result. Below, we factor . We will need the following claim.

Claim 4.6.

Under 1, .

Proof.

Proof of 3.3.

Write for . Under 1, substituting 4.6 into 4.5 with and taking from 2 yields

In particular, if , then and

| (7) |

This implies via the steps below:

Indeed, substituting from (7) and from 4.3 and yields

The second line uses the hypothesis to bound

Otherwise, if , then substituting from 3.2 and yields

Finally, for all ,

Substituting and into 4.1 with the following simplification

yields the desired bound. ∎

We now turn to the proof of 4.5. We first need to prove a technical lemma on the distance between orthogonal matrices. Below, denotes the set of orthonormal matrices.

Lemma 4.7.

Let and satisfy and . Then,

Proof.

Let Define where is the usual SVD. The choice of yields

Step (a) is because our choice of renders . Step (b) is because of , which follows from . The proof for follows identical steps with the choice of . ∎

5 Solution via MINRES

Let us estimate the cost of solving (5) using MINRES, as in 3.4. In the initial setup, we spend time and memory to explicitly compute the diagonal matrix , and to implicitly set up via their constituent matrices , and . Afterwards, each matrix-vector product with can be evaluated in time and memory, because and

Therefore, the per-iteration cost of MINRES, which is dominated by a single matrix-vector product with the augmented matrix in (5a), is time and memory, plus a single matrix-vector product with and . This is also the cost of evaluating the recovery equation in (5b).

We now turn to the number of iterations. 2.2 says that MINRES converges to residual in iterations, where is the condition estimate from 3.3, but we need the following lemma to ensure that small residual in (5a) would actually recover through (5b) a small-residual solution to our original problem (Newt-).

Lemma 5.1 (Propagation of small residuals).

Given where and and . Let

| (8) |

Then, and satisfy the following

| (9) |

where .

Proof.

Define as the exact solution to the following system of equations

Our key observation is that the matrix has two possible block factorizations

| (10) | ||||

| (11) |

where is via the Sherman–Morrison–Woodbury identity. We verify from (10) and (11) respectively that

and . Now, for a given , the associated errors are

and these can be rearranged as

It follows from our first block-triangular factorization (10) that

It follows from our second block-triangular factorization (11) that

We obtain (9) by isolating the first two block-rows, rescaling the first block-row by , and then substituting as an exact solution. ∎

6 Solution via indefinite PCG

Let us estimate the cost of solving (5) using indefinite PCG, as in 3.5. After setting up in the same way as using MINRES, we spend time and memory to explicitly form the Schur complement of the preconditioner

where . This can be done using matrix-vector products with and , which under 3, can each be evaluated in at time and memory:

where and . After forming the Schor complement , the indefinite preconditioner can be applied in its block triangular form

as a linear solve with , and a matrix-vector products with each of and , for time and memory. Moreover, note that under 3, each matrix-vector product with and costs time and memory. Therefore, the per-iteration cost of PCG, which is dominated by a single matrix-vector product with the augmented matrix in (5a) and a single application of the indefinite preconditioner, is time and memory.

We now turn to the number of iterations. 2.5 says that indefinite PCG will generate identical iterates to regular PCG applied to the following problem

with preconditioner and iterates that exactly satisfy

Plugging these iterates back into (5a) yields

and plugging into 5.1 and 2.4 shows that the recovered from (5b) will satisfy

where . We use the following argument to estimate .

Claim 6.1.

Let satisfy . Then

Proof.

We have because . We have because . ∎

Therefore, given that holds by hypothesis, it takes at most iterations to achieve , where

Finally, we bound and .

7 Experiments

We perform extensive experiments on challenging instances of robust matrix completion (RMC) and sensor network localization (SNL) problems, where the number of constraints is large, i.e., . We show that these two problems satisfy our theoretical assumptions and therefore our proposed method can solve them to high accuracies in time and memory. This is a significant improvement over general-purpose IPM solvers, which often struggle to solve SDP instances with constraints to high accuracies. Direct methods are computationally expensive, requiring time and memory to solve (2), and iterative methods are also ineffective, as they require iterations to solve (2) due to the ill-conditioned in . In contrast, our method reformulates (2) into a well-conditioned indefinite system that can be solved in time and memory, ensuring rapid convergence to a high accuracy solution.

All of our experiments are performed on an Apple laptop in MATLAB R2021a, running a silicon M1 pro chip with 10-core CPU, 16-core GPU, and 32GB of RAM. We implement our proposed method, which we denoted as Our method, by modifying the source code of SeDuMi [41] to use (5) to solve (Newt-) while keeping all other parts unchanged. Specifically, at each iteration, we decompose the scaling point as in (4) with the rank parameter for some fixed , and then solve (5) using PCG as in Corollary 3.5 with chosen as the square of median eigenvalue of . We choose to modify SeDuMi in order to be consistent with the prior approach of Zhang and Lavaei [53], which we denoted as ZL17.

In Section 7.1, we empirically verify our theoretical results using RMC and SNL problems, which include Assumptions 1, 2 and 3; the well-conditioned indefinite system predicted in Theorem 3.3; the bounded pcg iterations predicted in Corollary 3.5; and the cubic time complexity. In Section 7.2, we compare the practical performance of Our method for solving RMC and SNL problems.

Robust matrix completion.

Given a linear operator , the task of robust matrix completion [16, 31, 21] seeks to recover a low-rank matrix from highly corrupted measurements , where is a sparse outlier noise, meaning that its nonzero entries can have arbitrary large magnitudes. RMC admits the following optimization problem

| (12) |

where the norm is used to encourage sparsity in , the nuclear norm regularizer is used to encourage lower rank in , and is the regularization parameter. In order to turn (12) into the standard form SDP, we focus on symmetric, positive semidefinite variance of (12), meaning that , and the problem is written

| (13) |

In the remainder of this section, we set and according to the “matrix completion” model, meaning that where is the matrix that randomly permutes and subsamples out of elements in . In each case, the ground truth is chosen as in which is orthogonal, and its elements are sampled as . We fix in all simulations. A small number of Gaussian outliers are added to the measurements, meaning that where except randomly sampled elements with .

Sensor Network Localization.

The task of sensor network localization is to recover the locations of sensors given the location of anchors ; the Euclidean distance between and for some ; and the Euclidean distance between and for some . Formally

| (14) | ||||

where and denote the set of indices for which and is specified, respectively. In general, (14) is a nonconvex problem and difficult to solve directly, but its solution can be approximated through the following SDP relaxation [1, 8]

| (15) | ||||

The sensor locations can be exactly recovered through when the SDP relaxation (14) is tight, which occurs if and only if [40]. In this experiment, we also consider a setting of SNL problem for which the outliers are presented, meaning that the distance measurements and are corrupted by outlier noise and . Here, and are nonzero only for a very small subset of pairs and , respectively. The SNL problem with outlier measurements can be solved via the following SDP

| (16) | ||||

In the remainder of this section, we generate ground truth sensor locations and anchor locations from the standard uniform distribution. We fix and for all simulations. We randomly select out of indices to be in , and out of indices to be in . Gaussian outliers and are added to the distance measurement for all and for all , respectively. Here, except randomly sampled elements with , and except randomly sampled elements with . For simplicity, we use to denote the number of constraints and to denote the number of outliers in (16).

7.1 Validation of our theoretical results

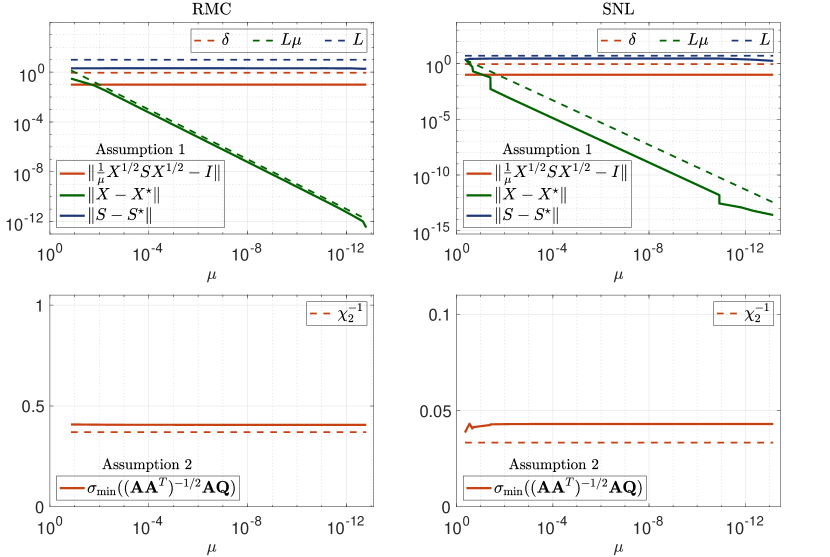

Assumptions 1 and 2.

We start by verifying Assumptions 1 and 2 hold for both RMC (13) and SNL (16) problems. In Figure 2, we empirically verify both assumptions using a small-scaled RMC problem, which is generated with , and a small-scaled SNL problem, which is generated with . As shown in Figure 2, both assumptions hold for the RMC and SNL problems with and , respectively. For these results, we run Our method and extract the primal variable , dual variable , and scaling point at each iteration. For each , and , the corresponding is chosen such that , and the corresponding matrix is constructed as in (4) with the rank parameter .

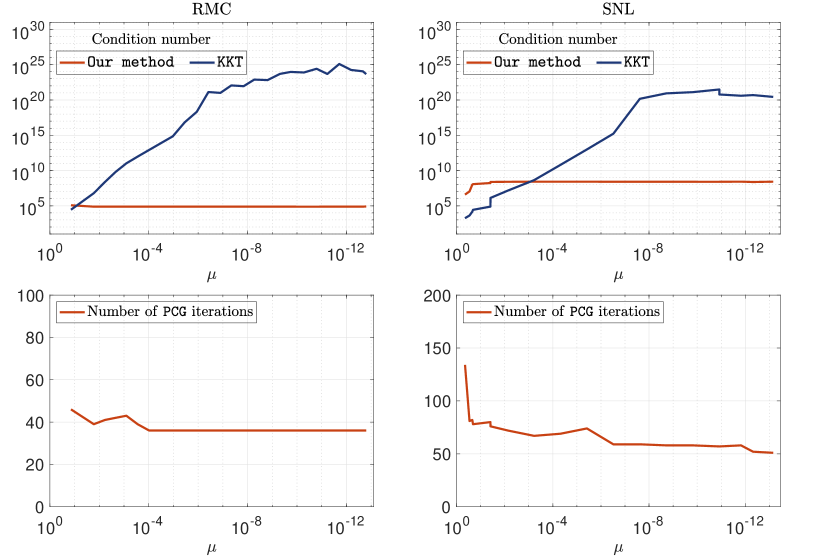

Bounded condition number and PCG iterations.

As the two assumptions hold for both problems, Theorem 3.3 proves that the condition number of the corresponding indefinite system (5) is bounded and independent of . Additionally, Corollary 3.5 shows that the indefinite system can be efficiently solved using PCG, and the number of iterations required to satisfy residual condition (Newt-) is independent of .

In Figure 3, we plot the condition number of our indefinite system (5) and the KKT equations (Newt-), as well as the number of PCG iterations required to satisfy residual condition (Newt-) with respect to different values of . We use the same instance of RMC (13) and SNL (16) in Figure 2. For each problem, we extract and as in Figure 2. For each pair of and , the corresponding indefinite system is constructed as in (5) using the rank parameter , and the corresponding KKT equations are constructed as in (Newt-). We run PCG to solve the indefinite system until the residual condition (Newt-) is satisfied with . In both cases, we see that the condition number of the indefinite system is upper bounded, while the condition number of the KKT equations (Newt-) explodes as . (We note that it becomes stuck at due to finite precision.) The number of PCG iterations for satisfy residual condition (Newt-) is also bounded and independent of .

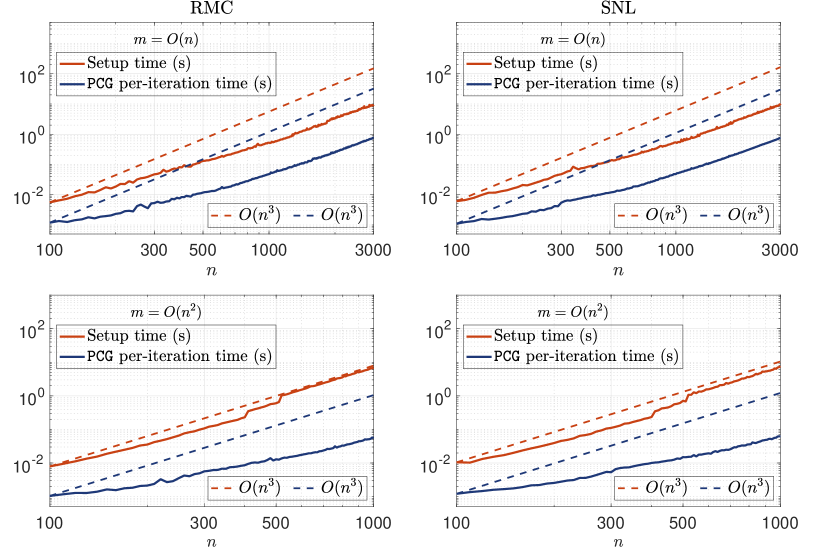

Cubic time complexity.

Finally, we verify Our method achieves cubic time complexity when Assumption 3 holds and , with no dependence on the number of constraints . We first prove both RMC (13) and SNL (16) satisfy Assumption 3. Given any and . For RMC, it is obvious that both and can be evaluated in time and storage. For SNL, by first paying time to calculate , observe that

can all be evaluated in time. (Notice that in SNR.) Therefore, when , which is common in real-world applications where there are typically more sensors than anchors, both and can be evaluated in time and storage.

In Figure 4, we plot the average setup time for the indefinite system (5) and the average per PCG iteration time against for both RMC and SNL problem. Specifically, the setup time includes: the time to decompose and construct in order to implicitly setup , , and as in (4); explicitly form the Schur complement via matrix-vector product with and ; and compute the Cholesky factor of . We consider two cases, and , in order to verify the time complexity of Our method is indeed invariant to . For both problem, we set the number of constraints to be for the case of , and for the case of . As we are interested in measuring the run time of Our method for solving the standard form SDP (1a), we fix to eliminate all the LP constraint in (13) and (16). As shown in Figure 4, the setup time and per PCG time exhibit cubic time complexity for both problems.

7.2 Comparison against other approaches

| Our method | MOSEK | ZL17 | ADMM | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error | Time | Error | Time | Error | Time | Error | Time | |||

| 100 | 3000 | 12 | 1.2s | 2.5s | 1.6s | 24.6s | ||||

| 100 | 4000 | 24 | 1.0s | 5.3s | 1.7s | 25.9s | ||||

| 100 | 5000 | 48 | 2.2s | 6.8s | 2.2s | 152s | ||||

| 300 | 40000 | 50 | 21.7s | 1853s | 31.3s | 84.2s | ||||

| 300 | 42500 | 100 | 23.9s | 2218s | 42.0s | 48.5s | ||||

| 300 | 45000 | 150 | 32.1s | 2310s | 67.9s | 50.1s | ||||

| 500 | 115000 | 100 | 127s | Out of memory | 154s | 103s | ||||

| 500 | 120000 | 200 | 138s | Out of memory | 260s | 180s | ||||

| 500 | 125000 | 300 | 127s | Out of memory | 233s | 314s | ||||

| 1000 | 400000 | 150 | 1011s | Out of memory | 2253s | 522s | ||||

| 1000 | 450000 | 300 | 954s | Out of memory | 1675s | 594s | ||||

| 1000 | 500000 | 450 | 1106s | Out of memory | 1458s | 1027s | ||||

In this section, we compare the practical performance of Our method for solving both robust matrix completion and sensor network localization problems.

Robust matrix completion.

First-order methods, such as linearized alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) [50, 19], can be used to solve (12) via the following iterations:

| (17) | ||||

where , is the step size, , denotes the projection of onto a set of rank- matrices, and is the soft-thresholding operator. While fast, the convergence of ADMM is not guaranteed without additional assumption on , such as requiring to be incoherent in the context of matrix completion. This makes it less reliable for obtaining high accuracy solutions.

Alternatively, the Burer–Monteiro (BM) approach can be applied by substituting where and . Unfortunately, as we explained in the introduction, the Burer–Monteiro approach is not able to solve the problem satisfactorily as it would either solve the problem by substituting into (12) or (13). The former is an unconstrained nonsmooth problem, which can be solved via subgradient (SubGD) method with step-size and . The latter is a constrained twice-differentiable problem, which can be solved via nonlinear programming (NLP) solver like Fmincon [33] and Knitro [13]. But in both cases, local optimization algorithms can struggle to converge, because the underlying nonsmoothness of the problem is further exacerbated by the nonconvexity of the BM factorization.

A promising alternative is to solve (13) via general-purpose IPM solver such as MOSEK [34]. However, general-purpose IPM incurs at least time and memory, which is concerning for problem instances with measurements.

Instead, we present experimental evidence to show that Our method is the most reliable way of solving RMC to high accuracies. We start by demonstrating the efficiency and efficacy of Our method by solving a large-scaled RMC, which is generated with . In Figure 1, we plot the reconstruction error against runtime for Our method, ZL17, Fmincon, Knitro, ADMM and SubGD. Here, the maximum rank parameter for Our method, and the search rank for Fmincon, Knitro, ADMM and SubGD are all set to be . We initialized Fmincon, Knitro and SubGD at the same initial point that is drawn from standard Gaussian, and initialized ADMM at . The step-size of ADMM and SubGD is set be and , respectively. From Figure 1, we see that Our method is the only one that is able to achieve reconstruction error below . Though both ADMM and ZL17 achieves reconstruction error at the fastest rate, they cannot make any further progress; ADMM becomes stuck and ZL17 becomes ill-conditioned. Comparing to nonlinear programming solvers, both Fmincon and Knitro eventually reach the same reconstruction error similar to ZL17 but at a significantly slower rate than Our method. Finally, SubGD converges extremely slowly for this problem.

In Table 1, we solve several instances of RMC problems using Our method, MOSEK, ZL17 and ADMM, and report their corresponding reconstruction error and runtime. For space efficiency, we omit the comparison with Knitro, Fmincon and SubGD as they generally perform worse than ADMM. In this experiment, the maximum rank parameter for Our method and the search rank for ADMM are all set to be . The number of iterations for ADMM is set to be . For all four methods, we report the best reconstruction error and the time they achieve their best reconstruction error. From Table 1, we see that Our method consistently achieves reconstruction error around in all cases, with runtime similar to ZL17. For and larger, MOSEK runs out of memory. We note that we pick the largest possible step size for ADMM that allows it to stably converge to the smallest error.

Sensor network localization.

We again demonstrate the efficiency and efficacy of Our method by solving a large-scale SNL problem, which is generated with . Similar to RMC, SNL can also be solved via Fmincon, Knitro, ADMM and SubGD. In particular, ADMM can be applied by first rewriting (16) into the standard form , and then apply (17) with . The SubGD method can subsequently be applied with the update , where , , and . Finally, both Fmincon and Knitro can be applied by substituting into (16).

In Figure 5, we plot the reconstruction error against runtime for Our method, ZL17, Fmincon, Knitro, ADMM and SubGD. The reconstruction error for SNL is defined as where . Here, the maximum rank parameter for Our method, and the search rank for Fmincon, Knitro, ADMM and SubGD are all set to be . We initialized Fmincon, Knitro and SubGD at the same initial point that is drawn from standard Gaussian, and initialized ADMM at . The step-size of ADMM and SubGD is set be and , respectively. From Figure 5, we again see that Our method is the only one that is able to achieve reconstruction error around at the fastest rate.

In Table 2, we solve several instances of SNL problems using Our method, MOSEK, ZL17 and Knitro, and report their corresponding reconstruction error and runtime. For simplicity, we omit the comparison with ADMM, Fmincon, and SubGD as they generally perform worse than Knitro. In this experiment, the maximum rank parameter for Our method and the search rank for Knitro are all set to be . The number of iterations for Knitro is set to be . For all four method, we report the best reconstruction error and the time they achieve their best reconstruction error. As shown in Table 2, Our method again consistently achieves reconstruction error around in all cases, with runtime similar to ZL17. For and larger, MOSEK runs out of memory.

| Our method | MOSEK | ZL17 | Knitro | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error | Time | Error | Time | Error | Time | Error | Time | |||

| 50 | 1000 | 30 | 1.0s | 0.6s | 1.1s | 7.0s | ||||

| 50 | 1150 | 40 | 0.7s | 0.5s | 0.8s | 9.2s | ||||

| 50 | 1300 | 50 | 0.6s | 0.7s | 0.8s | 14.6s | ||||

| 100 | 3000 | 60 | 2.2s | 3.2s | 3.1s | 64.4s | ||||

| 100 | 4000 | 80 | 2.9s | 4.4s | 3.4s | 53.7s | ||||

| 100 | 5000 | 100 | 4.1s | 7.8s | 3.8s | 59.2s | ||||

| 300 | 40000 | 220 | 108.5s | 1801s | 136.2s | 415.4s | ||||

| 300 | 42500 | 260 | 95.3s | 2439s | 119.3s | 275.9s | ||||

| 300 | 45000 | 300 | 117.5s | 3697s | 111.7s | 749.0s | ||||

| 500 | 100000 | 420 | 499.3s | Out of memory | 592.8s | 2548s | ||||

| 550 | 110000 | 460 | 559.4s | Out of memory | 747.7s | 1081s | ||||

| 500 | 120000 | 500 | 760.5s | Out of memory | 955.5s | 595.0s | ||||

References

- [1] A. Y. Alfakih, A. Khandani, and H. Wolkowicz, Solving euclidean distance matrix completion problems via semidefinite programming, Computational optimization and applications, 12 (1999), pp. 13–30.

- [2] F. Alizadeh, J.-P. A. Haeberly, and M. L. Overton, Complementarity and nondegeneracy in semidefinite programming, Mathematical Programming, 77 (1997), pp. 111–128.

- [3] T. Ando, Concavity of certain maps on positive definite matrices and applications to hadamard products, Linear Algebra and its Applications, 26 (1979), pp. 203–241.

- [4] S. Bellavia, J. Gondzio, and B. Morini, A matrix-free preconditioner for sparse symmetric positive definite systems and least-squares problems, SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing, 35 (2013), pp. A192–A211.

- [5] S. Bellavia, J. Gondzio, and M. Porcelli, An inexact dual logarithmic barrier method for solving sparse semidefinite programs, Mathematical Programming, 178 (2019), pp. 109–143.

- [6] S. J. Benson, Y. Ye, and X. Zhang, Solving large-scale sparse semidefinite programs for combinatorial optimization, SIAM Journal on Optimization, 10 (2000), pp. 443–461.

- [7] L. Bergamaschi, J. Gondzio, and G. Zilli, Preconditioning indefinite systems in interior point methods for optimization, Computational Optimization and Applications, 28 (2004), pp. 149–171.

- [8] P. Biswas and Y. Ye, Semidefinite programming for ad hoc wireless sensor network localization, in Proceedings of the 3rd international symposium on Information processing in sensor networks, 2004, pp. 46–54.

- [9] E. Y. Bobrovnikova and S. A. Vavasis, Accurate solution of weighted least squares by iterative methods, SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications, 22 (2001), pp. 1153–1174.

- [10] N. Boumal, Nonconvex phase synchronization, SIAM Journal on Optimization, 26 (2016), pp. 2355–2377.

- [11] N. Boumal, V. Voroninski, and A. S. Bandeira, Deterministic guarantees for burer-monteiro factorizations of smooth semidefinite programs, Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, 73 (2020), pp. 581–608.

- [12] S. Burer and R. D. Monteiro, A nonlinear programming algorithm for solving semidefinite programs via low-rank factorization, Math. Program., 95 (2003), pp. 329–357.

- [13] R. H. Byrd, J. Nocedal, and R. A. Waltz, K nitro: An integrated package for nonlinear optimization, Large-scale nonlinear optimization, (2006), pp. 35–59.

- [14] J.-F. Cai, E. J. Candès, and Z. Shen, A singular value thresholding algorithm for matrix completion, SIAM Journal on Optimization, 20 (2010), pp. 1956–1982.

- [15] E. Candès and B. Recht, Exact matrix completion via convex optimization., Foundations of Computational Mathematics, 9 (2009).

- [16] E. J. Candès, X. Li, Y. Ma, and J. Wright, Robust principal component analysis?, Journal of the ACM (JACM), 58 (2011), pp. 1–37.

- [17] E. J. Candes and Y. Plan, Tight oracle inequalities for low-rank matrix recovery from a minimal number of noisy random measurements, IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 57 (2011), pp. 2342–2359.

- [18] E. J. Candes, T. Strohmer, and V. Voroninski, Phaselift: Exact and stable signal recovery from magnitude measurements via convex programming, Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, 66 (2013), pp. 1241–1274.

- [19] Y. Cherapanamjeri, K. Gupta, and P. Jain, Nearly optimal robust matrix completion, in International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, 2017, pp. 797–805.

- [20] H.-M. Chiu and R. Y. Zhang, Tight certification of adversarially trained neural networks via nonconvex low-rank semidefinite relaxations, in International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, 2023, pp. 5631–5660.

- [21] L. Ding, L. Jiang, Y. Chen, Q. Qu, and Z. Zhu, Rank overspecified robust matrix recovery: Subgradient method and exact recovery, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34 (2021), pp. 26767–26778.

- [22] V. Faber and T. Manteuffel, Necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of a conjugate gradient method, SIAM Journal on numerical analysis, 21 (1984), pp. 352–362.

- [23] M. Fukuda, M. Kojima, K. Murota, and K. Nakata, Exploiting sparsity in semidefinite programming via matrix completion I: General framework, SIAM J. Optim., 11 (2001), pp. 647–674.

- [24] J. Gondzio, Matrix-free interior point method, Computational Optimization and Applications, 51 (2012), pp. 457–480.

- [25] N. I. Gould, Iterative methods for ill-conditioned linear systems from optimization, Springer, 2000.

- [26] A. Greenbaum, Iterative methods for solving linear systems, SIAM, 1997.

- [27] S. Habibi, M. Kočvara, and M. Stingl, Loraine–an interior-point solver for low-rank semidefinite programming, Optimization Methods and Software, (2023), pp. 1–31.

- [28] S. Kim, M. Kojima, M. Mevissen, and M. Yamashita, Exploiting sparsity in linear and nonlinear matrix inequalities via positive semidefinite matrix completion, Math. Program., 129 (2011), pp. 33–68.

- [29] L. Lukšan and J. Vlček, Indefinitely preconditioned inexact newton method for large sparse equality constrained non-linear programming problems, Numerical linear algebra with applications, 5 (1998), pp. 219–247.

- [30] Z.-Q. Luo, J. F. Sturm, and S. Zhang, Superlinear convergence of a symmetric primal-dual path following algorithm for semidefinite programming, SIAM Journal on Optimization, 8 (1998), pp. 59–81.

- [31] J. Ma and S. Fattahi, Global convergence of sub-gradient method for robust matrix recovery: Small initialization, noisy measurements, and over-parameterization, Journal of Machine Learning Research, 24 (2023), pp. 1–84.

- [32] S. Maniu, P. Senellart, and S. Jog, An experimental study of the treewidth of real-world graph data, in 22nd International Conference on Database Theory (ICDT 2019), Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik, 2019.

- [33] Matlab optimization toolbox, 2021. The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA.

- [34] MOSEK ApS, The MOSEK optimization toolbox for MATLAB manual. Version 7.1 (Revision 28)., 2015.

- [35] Y. E. Nesterov and M. J. Todd, Self-scaled barriers and interior-point methods for convex programming, Mathematics of Operations research, 22 (1997), pp. 1–42.

- [36] , Primal-dual interior-point methods for self-scaled cones, SIAM Journal on optimization, 8 (1998), pp. 324–364.

- [37] B. Recht, M. Fazel, and P. A. Parrilo, Guaranteed minimum-rank solutions of linear matrix equations via nuclear norm minimization, SIAM review, 52 (2010), pp. 471–501.

- [38] D. M. Rosen, L. Carlone, A. S. Bandeira, and J. J. Leonard, Se-sync: A certifiably correct algorithm for synchronization over the special euclidean group, The International Journal of Robotics Research, 38 (2019), pp. 95–125.

- [39] M. Rozlozník and V. Simoncini, Krylov subspace methods for saddle point problems with indefinite preconditioning, SIAM journal on matrix analysis and applications, 24 (2002), pp. 368–391.

- [40] A. M.-C. So and Y. Ye, Theory of semidefinite programming for sensor network localization, Mathematical Programming, 109 (2007), pp. 367–384.

- [41] J. F. Sturm, Using SeDuMi 1.02, a MATLAB toolbox for optimization over symmetric cones, Optimization methods and software, 11 (1999), pp. 625–653.

- [42] , Implementation of interior point methods for mixed semidefinite and second order cone optimization problems, Optim. Method. Softw., 17 (2002), pp. 1105–1154.

- [43] J. F. Sturm and S. Zhang, Symmetric primal-dual path-following algorithms for semidefinite programming, Applied Numerical Mathematics, 29 (1999), pp. 301–315.

- [44] K.-C. Toh, Solving large scale semidefinite programs via an iterative solver on the augmented systems, SIAM Journal on Optimization, 14 (2004), pp. 670–698.

- [45] K.-C. Toh and M. Kojima, Solving some large scale semidefinite programs via the conjugate residual method, SIAM Journal on Optimization, 12 (2002), pp. 669–691.

- [46] K.-C. Toh, M. J. Todd, and R. H. Tütüncü, Sdpt3–a matlab software package for semidefinite programming, version 1.3, Optimization methods and software, 11 (1999), pp. 545–581.

- [47] L. Vandenberghe and S. Boyd, Semidefinite programming, SIAM review, 38 (1996), pp. 49–95.

- [48] S. J. Wright, Primal-dual interior-point methods, SIAM, 1997.

- [49] H. Yang, L. Liang, L. Carlone, and K.-C. Toh, An inexact projected gradient method with rounding and lifting by nonlinear programming for solving rank-one semidefinite relaxation of polynomial optimization, Mathematical Programming, 201 (2023), pp. 409–472.

- [50] X. Yuan and J. Yang, Sparse and low-rank matrix decomposition via alternating direction methods, preprint, 12 (2009).

- [51] A. Yurtsever, J. A. Tropp, O. Fercoq, M. Udell, and V. Cevher, Scalable semidefinite programming, SIAM Journal on Mathematics of Data Science, 3 (2021), pp. 171–200.

- [52] R. Y. Zhang, Parameterized complexity of chordal conversion for sparse semidefinite programs with small treewidth, arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.15288, (2023).

- [53] R. Y. Zhang and J. Lavaei, Modified interior-point method for large-and-sparse low-rank semidefinite programs, in IEEE 56th Conference on Decision and Control, 2017.

- [54] , Sparse semidefinite programs with guaranteed near-linear time complexity via dualized clique tree conversion, Mathematical programming, 188 (2021), pp. 351–393.

Appendix A Proof of Proposition 3.2

We break the proof into three parts. Below, recall that we have defined as the basis matrix for on , in order to define for , and for .

Lemma A.1 (Correctness).

Let where is orthonormal, and pick . Define and . Then

Proof.

Write and . For arbitrary , it follows from that

Now, substituting yields our desired claim:

Indeed, we verify that and , where we used because . ∎

Lemma A.2 (Column span of ).

Let be orthonormal with . Define where and . Then, and where .

Proof.

Without loss of generality, let . We observe that

holds for any arbitrary (possibly nonsymmetric) and , and that for all , so . ∎

Lemma A.3 (Eigenvalue bounds on and ).

Given , write for all . Choose and , and define where and where and . Then,

Proof.

We have and . Similarly, and . We have because and while Finally, we have because . ∎