11email: [email protected] 22institutetext: AIM, CEA, CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France33institutetext: INAF - IASF Milan, via A. Corti 12, I-20133 Milano, Italy44institutetext: INAF - Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio di Bologna, via Piero Gobetti 93/3, I-40129 Bologna, Italy 55institutetext: INFN, Sezione di Bologna, viale Berti Pichat 6/2, I-40127 Bologna, Italy 66institutetext: Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics (ASIAA), No. 1, Section 4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei 10617, Taiwan 77institutetext: Université Aix-Marseille, CNRS, LAM (Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille) UMR 7326, 13388 Marseille, France88institutetext: Sub-department of Astrophysics, University of Oxford, Denys Wilkinson Building, Keble Road, Oxford, OX1 2DL, UK99institutetext: European Southern Observatory, Alonso de Cordova 3107, Vitacura, Santiago 19001, Chile1010institutetext: Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville, Cape Town, 7535, South Africa1111institutetext: Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics, Space Applications & Remote Sensing, National Observatory of Athens, GR-15236 Palaia Penteli, Greece1212institutetext: CEA Saclay, DRF/Irfu/DEDIP/LILAS, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette Cedex, France 1313institutetext: Argelander Institut für Astronomie, Universität Bonn, Auf dem Huegel 71, DE-53121 Bonn, Germany1414institutetext: INAF-Astronomical Observatory of Padova, vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy

The XXL survey

Abstract

Context. Distant galaxy clusters provide an effective laboratory in which to study galaxy evolution in dense environments and at early cosmic times.

Aims. We aim to identify distant galaxy clusters as extended X-ray sources coincident with overdensities of characteristically bright galaxies.

Methods. We use optical and near-infrared (NIR) data from the Hyper Suprime-Cam (HSC) and VISTA Deep Extragalactic Observations (VIDEO) surveys to identify distant galaxy clusters as overdensities of bright, galaxies associated with extended X-ray sources detected in the ultimate XMM extragalactic survey (XXL).

Results. We identify a sample of 35 candidate clusters at from an approximately 4.5 deg2 sky area. This sample includes 15 newly discovered candidate clusters, ten previously detected but unconfirmed clusters, and ten spectroscopically confirmed clusters. Although these clusters host galaxy populations that display a wide variety of quenching levels, they exhibit well-defined relations between quenching, cluster-centric distance, and galaxy luminosity. The brightest cluster galaxies (BCGs) within our sample display colours consistent with a bimodal population composed of an old and red subsample together with a bluer, more diverse subsample.

Conclusions. The relation between galaxy masses and quenching seem to be already in place at , although there is no significant variation of the quenching fraction with the cluster-centric radius. The BCG bimodality might be explained by the presence of a younger stellar component in some BCGs but additional data are needed to confirm this scenario.

Key Words.:

Galaxies: clusters: general – Galaxies: distances and redshifts – Galaxies: evolution – Galaxies: high-redshift – Galaxies: photometry – X-rays: galaxies: clusters1 Introduction

Galaxy clusters are the most massive gravitationally bound structures at any epoch. Clusters are dark matter dominated (% of the total mass), while a hot X-ray emitting intracluster medium (ICM) accounts for most of the baryonic mass of the cluster (Plionis et al. 2008). Stars and galaxies correspond to less than 5% of the total mass (Plionis et al. 2008). Clusters provide one of the most extreme environments in universe: infalling galaxies are stripped of their gas by the intracluster medium ram pressure (e.g. Poggianti et al. 2004, 2008, 2016, 2019; Jaffé et al. 2018; Tonnesen 2019) while the centre is one of the densest environments found in space.

The formation and evolution of the most massive giant elliptical galaxies, the Brightest Cluster Galaxies (BCGs), is intimately related to the cluster environment. Located near the gravitational centre of the galaxy cluster, they exhibit unique properties such as distinct luminosity and surface brightness profiles, and/or supersolar metallicities (e.g. Oemler 1976; Tremaine & Richstone 1977; Dressler 1978; Von Der Linden et al. 2007; Loubser et al. 2009). The classical formation scenario of these galaxies, proposed by De Lucia & Blaizot (2007), is one of early star formation (mostly before ), quickly suppressed by AGN feedback (e.g Croton et al. 2006), and of progressive, late assembly via gas-poor mergers.

At low redshifts, BCG properties are generally consistent with this picture (e.g. Stott et al. 2008, 2011; Lidman et al. 2012; Bellstedt et al. 2016; Edwards et al. 2020), although several examples of low to moderately star-forming BCGs have been reported in individual, X-ray bright clusters (e.g. Egami et al. 2006; Bildfell et al. 2008; Stott et al. 2008; Pipino et al. 2009; Loubser et al. 2009, 2016; Rawle et al. 2012; Green et al. 2016). However, there is gathering evidence against the classical scenario at : Webb et al. (2015) and McDonald et al. (2016) report evidence of significant in-situ star formation in respectively % and % of their samples. The triggering mechanism of this star formation remains unknown, although McDonald et al. (2016) suggested galaxy interactions, a possibility supported by recent simulations (Rennehan et al. 2020).

The cessation of star formation activity, referred to as quenching, plays an important role in the evolution of galaxies – both for the BCG and within the cluster environment as a whole. Indeed, galaxies appear to evolve at an accelerated rate in clusters than in the field at all redshifts (e.g. Alberts et al. 2014; Nantais et al. 2017; Foltz et al. 2018; Jian et al. 2018; Pintos-Castro et al. 2019; Strazzullo et al. 2019), although it is unclear at which redshift the passive fraction in clusters becomes greater than in the field (e.g. Strazzullo et al. 2013, 2019; Brodwin et al. 2013; Alberts et al. 2014; Nantais et al. 2017). Quenching also depends on galaxy mass in the sense that higher mass galaxies are more quenched than those of lower mass (e.g. Muzzin et al. 2012; Balogh et al. 2016; Kawinwanichakij et al. 2017; Jian et al. 2018; Pintos-Castro et al. 2019). Because the most massive galaxies typically reside in the cluster core, mass and environmental effects are difficult to disentangle (e.g. Balogh & McGee 2010; Muzzin et al. 2012; Kawinwanichakij et al. 2017; Jian et al. 2018; Pintos-Castro et al. 2019) and require large samples of well-characterised galaxy clusters.

Galaxy clusters may be identified employing a range of techniques. Optical and infrared (IR) imaging surveys identify clusters as overdensities of galaxies (e.g. Postman et al. 1996; Gladders & Yee 2000, 2005; Euclid Collaboration et al. 2019). In the case of the red-sequence algorithm (Gladders & Yee 2000, 2005), as used in the recent Spitzer Adaptation of the Red-sequence Survey (SpARCS; e.g. Wilson et al. 2006, 2009), identified overdensities display colours consistent with the red-sequence at a given redshift. However, this red-sequence selection may introduce a bias toward clusters with enhanced red galaxy populations (e.g. Donahue et al. 2002; Willis et al. 2018). An alternative approach is to identify clusters using the properties of the intra-cluster medium, either indirectly via the Suyaev-Zel’dovich effect (e.g. Zel’dovich & Sunyaev 1969; Sunyaev & Zel’dovich 1970, 1972, 1980a, 1980b; Carlstrom et al. 2002; Bleem et al. 2015) or directly via X-ray bremsstrahlung emission (e.g. Gursky et al. 1972; Sarazin 1986; Pierre et al. 2004, 2016, hereafter XXL Paper I; Willis et al. 2018). X-ray selection has been successfully used in the past to find clusters of galaxies either alone (e.g. Vikhlinin et al. 1998; Clerc et al. 2012) or with the aid of optical data (e.g. Gioia et al. 1990; Böhringer et al. 2001; Willis et al. 2013). There is tentative evidence that such clusters sometimes display smaller red-sequence galaxy populations than optically selected clusters (Donahue et al. 2002; Willis et al. 2018), but a drawback is that X-ray selected samples can exhibit a bias toward relaxed, cool core clusters (e.g. Eckert et al. 2011; Rossetti et al. 2017; Willis et al. 2018) and lower BCG-X-ray peak distances (e.g. Lavoie et al. 2016, hereafter XXL Paper XV; Rossetti et al. 2016). Hence the need for cluster studies with various, complementary selected samples (e.g. Donahue et al. 2002; Sadibekova et al. 2014; Bleem et al. 2015; Willis et al. 2018).

In this paper we employ a multi-wavelength data set constructed as part of the XMM-XXL survey to identify distant galaxy clusters and study their galaxy populations. The XMM-XXL survey covers 50 divided into two equal fields: XXL-North and XXL-South (XXL-N and XXL-S; XXL Paper I, ). Each field is constructed from a mosaic of 10 ks XMM pointings. The present paper focuses on a contiguous sub-area of the XXL-N field covering 5.3 , XMM-SERVS, which has been observed with an exposure time of 46 ks per pointing (Chen et al. 2018). This deeper sub-area of XMM data is accompanied by a range of multi-wavelength optical and IR data (see XXL Paper I, ), including a high-quality data set generated by the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA) Deep Extragalatic Observations (VIDEO) survey (Jarvis et al. 2013). We refer to the 4.5 deg2 field with overlapping deep XMM and VIDEO data as the XXL-N/VIDEO field (see Fig. 1).

This paper presents the identification and characterisation of a sample of distant galaxy clusters selected from the XXL-N/VIDEO field. In Sects. 2 and 3 we describe the identification and composition of the cluster sample. In Sect. 4, we compute the fraction of quenched galaxies within the cluster sample and as a function of salient properties such as cluster-centric distance and galaxy luminosity. In Sect. 5 we identify a sample of BCGs from the cluster sample, and investigate the properties of their stellar populations and their star formation histories. In Sect. 6 we discuss the possible causes of the variety of observed cluster quenching fractions and of the BCG colour bimodality before summarizing our main conclusions in Sect. 7. We employ a WMAP9 cosmology characterised by , , and (Hinshaw et al. 2013). At redshifts of 1 and 1.5, an angular scale of one arcminute corresponds to 489 and 518 kpc respectively. All photometry is quoted in the AB magnitude system.

The present paper relies on the new version of XXL-XMM pipeline (V4), still in development, and on the related X-ray parameters and images. Compared to the V3 pipeline dealing with individual XMM observations (on which were based all previous XXL publications), the V4 pipeline processes co‐added observations assembled into mosaics. By dealing with pointing overlaps, V4 ensures reaching the ultimate sensitivity at any position (Faccioli et al. 2018, hereafter XXL Paper XXIV). This is especially important for the VIDEO region, characterized by a high level of redundancies.

Throughout this paper, we consider that a cluster is confirmed if at least 3 galaxies within the X-ray emission have matching spectroscopic redshifts, or if an obvious BCG has a spectroscopic redshift (Adami et al. 2018, hereafter XXL Paper XX). The expression ‘unconfirmed clusters’ will be used to refer to candidate clusters with insufficient information to be spectroscopically confirmed. Cluster names with the prefix ‘XLSSC’ pertain to spectroscopically confirmed clusters only and may be found in XXL Paper XX. Prefix ‘3XLSS’ refers to X-ray sources part of Chiappetti et al. (2018, XXL Paper XXVII) catalogue. New V4 detections are labelled by the prefix ‘XLSSU’.

2 Observations and cluster detection

In this paper, we attempt to identify significant galaxy overdensities observed in optical-IR imaging data associated with extended X-ray sources. We employ the galaxy photometric redshift (from the VIDEO catalogue) distribution of positive matches to select candidate distant clusters at .

2.1 X-ray data

In short, the Xamin pipeline tests four models to characterise the detected sources, generating likelihood estimates for point, extended, double point sources, and extended plus point source; this latter model, denoted AC, is intended to flag extended sources significantly contaminated by a central AGN. The coordinates of the X-ray source presented in Sect. 3 are based on the centre of the best-fit model. Cluster sources are further classified into C1 and C2 on the basis of pipeline parameters extent and extent_likelihood. The C1 sample corresponds to an almost pure sample of bright clusters, while the C2 sample, fainter, allows for 50% of misclassified point sources (i.e. up to 50% of the sample might be point sources; see Pacaud et al. 2006; XXL Paper XXIV). False C2 are routinely excluded by the examination of X-ray/optical overlays for cluster candidates below z=1.

We mention that the choice of the numerical pipeline parameter values used to define the C1 and C2 criteria are still those based on detections performed with the V3 pipeline from simulated individual XMM observations. These criteria will be revised when the final V4 is fully validated and applied to mosaic simulations. However, we do not expect drastic changes in the class parameters, since they are based on likelihoods. This situation does not impact the current study, because it does not explicitly involve the cluster selection function at any stage.

2.2 Optical and near infrared photometry

The VIDEO observations consist of IR imaging undertaken with the VISTA telescope in the photometric bands. In the XMM-SERVS field, these observations reach 5 depths of at least 25.1, 24.7, 24.2, and 23.8 mag within 2 arcsecond circular apertures for respectively (Adams et al. 2020). The VIDEO catalogue also contains additional imaging data consisting of the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope Legacy Survey Deep-1 field (CFHTLS-D1) and of the deep ‘layer’ of the Hyper Suprime-Camera (HSC) Subaru Strategic Program (HSC-SSP, Aihara et al. 2018a, b). The ultra-deep ‘layer’ of HSC-SSP overlaps with the XMM1 field. The photometric redshift analysis included in the catalogue employs an i-band selected source list where photometry in additional bands is obtained by applying SExtractor to astrometrically-matched pixel data at other wavelengths. In addition, we employ HSC-SSP and VIDEO photometry from this catalogue to study the properties of candidate cluster member galaxies directly. The HSC-SSP deep data have 5 limiting magnitudes of 25.4 and 24.6 respectively in the and bands, and the ultra-deep data have limiting magnitudes of 26.4 and 26.3 (Adams et al. 2020).

Photometric redshifts for sources in the VIDEO catalogue are computed using the LePhare photometric redshift code (Ilbert et al. 2006). The code employs the COSMO template set (Ilbert et al. 2009), including 32 templates from Polletta et al. (2007) and from Bruzual & Charlot (2003). Dust attenuation follows a Calzetti et al. (2000) law, and intergalactic medium absorption treatment is based on Madau (1995). Further details are provided by Adams et al. (2020).

2.3 Identification of galaxy clusters

We perform four steps to select candidate clusters from our X-ray sample, following a similar procedure to that of Willis et al. (2013). Each step is summarised below:

-

1.

Convolve the photometric redshift histogram for bright galaxies with a matched Gaussian filter chosen to match the properties of redshift peaks of spectroscopically confirmed clusters. Galaxies are selected to be brighter than the characteristic luminosity, , along the line-of-sight of each X-ray source (i.e. a one arcmin radius aperture centred on the X-ray best-fit model centre).

-

2.

Identify overdensities corresponding to a bright galaxy excess of , and display the position of potential members on colour images together with X-ray emission contours.

-

3.

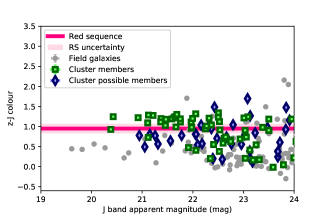

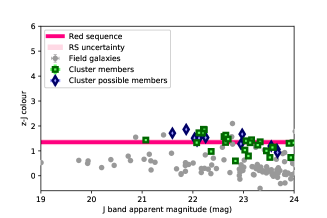

Examine the and colour-magnitude diagrams of each candidate cluster.

-

4.

Employ a Gaussian model of the photometric redshift distribution of selected overdensities to estimate a refined mean cluster redshift and its standard deviation.

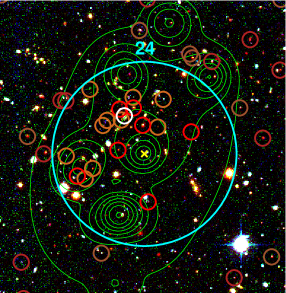

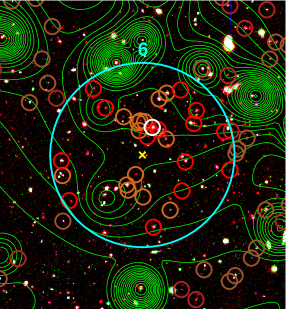

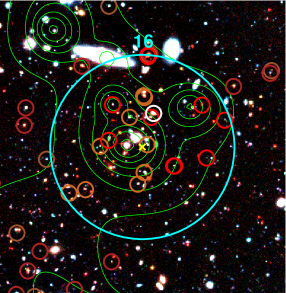

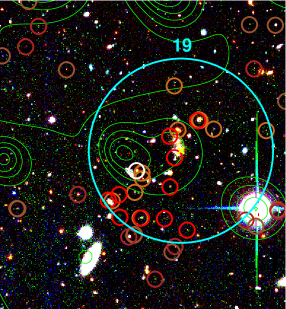

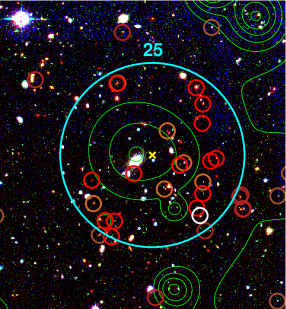

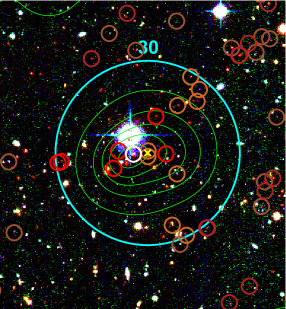

Figure 2 presents a visual summary of these four steps. Similar images of the other candidate clusters are presented in Appendix B.

The first step of the identification process is to select galaxies and active galactic nuclei (AGN) that might be associated with each X-ray sources. We select the galaxies and AGN sources employing their goodness-of-fit when compared to stellar, galactic, and AGN templates (see Jarvis et al. 2013). Because galaxies in clusters are more likely to host radio-loud AGN than field galaxies (Best et al. 2007), we keep AGN and discard only the star-like objects. Then, we select objects within one arcmin of the considered X-ray detection. We refer to these objects as the field-of-view galaxies.

We select bright galaxies in the field-of-view employing luminosity function arguments: we compute the apparent magnitude of , assuming in the band using Cirasuolo et al. (2010) with no evolution from to and a -correction described by the bandwidth term. Galaxies brighter than the expected apparent magnitude at their photometric redshift are retained. We apply a further photometric cut based on the 5 depth of VIDEO band, discarding any galaxy fainter than 23.8. The latter cut is important beyond , where is fainter than the VIDEO 5 limit.

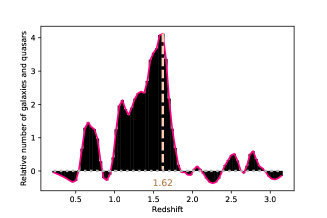

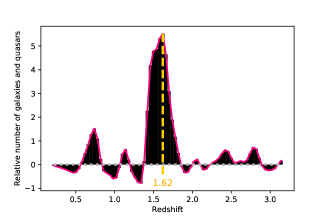

Selected field-of-view galaxies are then binned in photometric redshift space, over the interval . Galaxies are sampled in bins of 0.04 in photometric redshift since this is the redshift iteration step employed in the photometric redshift analysis. We then use the catalogue distribution to perform a background subtraction, applying the same selection steps described above and scaling the number distribution by the relative size of our field-of-view compared to that of the full the catalogue, i.e.

| (1) |

where is the number of galaxies in a particular redshift bin in our field-of-view, is the number of galaxies listed in the catalogue in the corresponding redshift bin after applying the same cuts, is the one arcminute radius we use to select galaxies associated with an X-ray detection, and is the catalogue area.

To identify structures in the photometric redshift histogram along the line-of-sight to each extended X-ray source we employ a matched Gaussian filter with a FWHM equal to 0.12 in redshift (i.e. 3 bins). The properties of the Gaussian profile are based upon the unfiltered redshift peaks associated with spectroscopically confirmed clusters.

2.4 Overdensity assessment

We perform a visual inspection of all C1, C2, and AC X-ray sources that display a signal consistent with galaxies at a single photometric redshift. We typically employ images from CFHTLS and VIDEO with candidate members indicated in addition to X-ray emission contours (see Fig. 2). We further generate and colour magnitude diagrams of each candidate cluster to determine if a red sequence is present.

The overdensity finding method provides a first estimate of the candidate cluster redshift based on the median redshift of the highest bins (see Fig. 2, bottom left panel). To refine this estimate, we model each candidate redshift signal as a Gaussian employing the 13 central bins of the non-filtered redshift signal. We then use the Gaussian mean as the cluster redshift and the standard deviations as a estimate of the uncertainty.

3 The cluster sample

| # | Nearest objecta | Flagsb | RA | Dec | Sign. | Notes | ||||

| (degrees) | (degrees) | () | () | |||||||

| 1 | 3XLSS J022222.9-044043 | US | 35.595 | -4.679 | 3.9 | 0.80 | 0.77 | - | - | g |

| 2 | XLSSC 184 | C | 35.312 | -4.207 | 7.4 | 0.80 | 0.81 | - | ||

| 3 | XLSSC 071 | C | 35.639 | -4.966 | 6.4 | 0.83 | 0.83 | - | ||

| 4 | 3XLSS J022432.9-044742 | U | 36.137 | -4.796 | 5.1 | 0.83 | 0.90 | - | ||

| 5 | 3XLSS J022135.2-051811 | C | 35.399 | -5.305 | 8.4 | 0.85 | 0.84 | - | ||

| 6 | XLSSU J021947.4-050841 | U | 34.948 | -5.145 | 5.0 | 0.86 | 0.89 | - | ||

| 7 | XLSSC 015 | C | 35.928 | -5.034 | 8.2 | 0.87 | 0.86 | - | ||

| 8 | XLSSC 064 | C | 34.632 | -5.018 | 9.2 | 0.89 | 0.87 | - | ||

| 9 | 3XLSS J022557.1-042845 | U | 36.489 | -4.480 | 4.0 | 0.90 | 1.05 | - | ||

| 10 | 3XLSS J022156.1-053049 | U | 35.483 | -5.513 | 3.8 | 0.91 | 0.95 | - | ||

| 11 | 3XLSS J021945.5-044831 | U | 34.935 | -4.814 | 4.9 | 0.91 | 0.92 | - | ||

| 12 | XLSSU J022530.3-042544 | C | 36.376 | -4.429 | 5.9 | 0.87 | 0.92 | - | ||

| 13 | 3XLSS J022804.6-045351 | U | 37.020 | -4.898 | 4.3 | 0.93 | 0.86 | - | ||

| 14 | XLSSU J022051.0-050958 | N | 35.213 | -5.166 | 6.6 | 0.97 | - | h | ||

| 15 | 3XLSS J022103.0-045524 | U | 35.260 | -4.924 | 5.1 | 0.97 | 1.10 | - | ||

| 16 | 3XLSS J022739.0-045830 | N | 36.909 | -4.976 | 3.9 | 0.99 | - | - | ||

| 17 | 3XLSS J022044.7-041713 | N | 35.185 | -4.287 | 4.1 | 1.00 | - | - | ||

| 18 | XLSSC 044 () | US | 36.141 | -4.235 | 4.9 | 1.00 | 1.13 | - | - | h |

| 19 | XLSSC 124 () | NS | 34.419 | -4.862 | 3.9 | 1.00 | - | - | - | h |

| 20 | XLSSC 029 | C | 36.016 | -4.225 | 8.3 | 1.06 | 1.05 | - | ||

| 21 | XLSSC 005 | C | 36.785 | -4.300 | 5.6 | 1.04 | 1.06 | - | ||

| 22 | XLSSC 192 () | NS | 34.507 | -5.023 | 4.6 | 1.08 | - | - | - | h |

| 23 | 3XLSS J022027.0-043538 | N | 35.111 | -4.595 | 4.7 | 1.09 | - | - | ||

| 24 | 3XLSS J022222.9-044043 | US | 35.595 | -4.679 | 4.0 | 1.12 | - | - | - | g |

| 25 | XLSSC 141 () | NS | 34.356 | -4.659 | 4.9 | 1.21 | - | - | - | - |

| 26 | XLSSC 046 | C | 35.762 | -4.605 | 9.0 | 1.18 | 1.21 | - | ||

| 27 | 3XLSS J022003.6-045142 | N | 35.016 | -4.861 | 5.1 | 1.44 | - | - | ||

| 28 | 3XLSS J022255.1-043508 | N | 35.726 | -4.587 | 4.5 | 1.45 | - | - | ||

| 29 | 3XLSS J022100.4-042327 | N | 35.250 | -4.392 | 4.2 | 1.48 | - | - | ||

| 30 | 3XLSS J022207.4-044532 | N | 35.529 | -4.758 | 3.9 | 1.49 | - | - | ||

| 31 | XLSSU J022105.6-043935 | N | 35.265 | -4.656 | 4.1 | 1.54 | - | - | ||

| 32 | 3XLSS J022010.3-050701 | N | 35.043 | -5.117 | 5.5 | 1.57 | - | - | ||

| 33 | 3XLSS J022806.4-044803 | N | 37.025 | -4.797 | 4.9 | 1.79 | - | - | ||

| 34 | JKCS 041 | C | 36.683 | -4.694 | 8.2 | 1.63 | 1.80 | - | ||

| 35 | 3XLSS J022734.1-041021 | N | 36.891 | -4.174 | 4.0 | 1.93 | - | - | ||

| a Nearest confirmed cluster or X-ray source. If the nearest object is a confirmed foreground cluster, its spectroscopic redshift, , is given. | ||||||||||

| b C: spectroscopically confirmed cluster; U (for unconfirmed): not spectroscopically confirmed, but listed as a candidate cluster in the literature; N: New candidate cluster; S: superposition with a low redshift confirmed cluster or with another candidate | ||||||||||

| c The uncertainties on the photometric redshifts are estimated to 0.02 at and 0.14 at | ||||||||||

| d Spectroscopic redshifts (flag C) reported from Pierre et al. (2006); Willis et al. (2013); Andreon et al. (2014); XXL Paper XX | ||||||||||

| e Tentative or photometric redshifts (flag U) reported from Finoguenov et al. (2010); Durret et al. (2011); Wen & Han (2011); Licitra et al. (2016); XXL Paper XX | ||||||||||

| f We do not compute a X-ray luminosity for clusters marked S (superposition), because their X-ray emission might be a blend of foreground and background emission. | ||||||||||

| g Archival spectroscopic observations available. | ||||||||||

| h Gemini GMOS observations under proprietary time. | ||||||||||

3.1 Sample selection

We processed a total of 284 extended X-ray detections within the XXL-N/VIDEO region. This parent sample generated a sample of 35 candidate distant galaxy clusters. Table 1 and Fig. 3 present these clusters, each of which represents a detection with a significance of approximately four galaxies or more in a photometric redshift bin satisfying (see also Fig. 1). Of these 35 candidate clusters, ten are spectroscopically confirmed while 15 are presented here for the first time. Ten additional candidates have been previously identified as distant clusters but, to our knowledge, never spectroscopically confirmed (see Olsen et al. 2007; Finoguenov et al. 2010; Durret et al. 2011; Wen & Han 2011; Licitra et al. 2016; XXL Paper XX).

Nine of the confirmed cluster detections were confirmed by prior spectroscopy (e.g. Pierre et al. 2006; Willis et al. 2013; XXL Paper XX), including one at (Andreon et al. 2014). With the spectroscopic redshifts listed in the CESAM database111http://cesam.lam.fr/xmm-lss/ (XXL Paper XX), we were able to confirm one additional cluster (candidate 3), bringing the total number of confirmed cluster to ten. All of these X-ray detections meet our candidate clusters criteria.

Four confirmed distant clusters in this area (Pierre et al. 2006; Papovich et al. 2010; XXL Paper XX), are not part of our sample because their coordinates do not correspond to a V4 C1, C2, or AC detection. This is the case for a cluster (Papovich et al. 2010). Although IRC-0218A and our detections at similar redshifts possess comparable masses (IRC-0218A is ), IRC-0218A X-ray emission is completely dominated by a point source (Pierre et al. 2012).

We nevertheless applied our optical/IR detection criteria to those four clusters. Two clusters satisfied these criteria, including IRC-0218A, and were included in our photometric redshift accuracy assessment (see the following section). The clusters XLSS J022609.9-043120 and XLSSC 203 (see Pierre et al. 2006; XXL Paper XX) located respectively at and , did not satisfy them. Because V4 works on co-added and thus deeper images, we expect its source characterisation to be more reliable.

3.2 Photometric redshift accuracy

To estimate the reliability of our photometric redshift estimates for the candidate clusters, we compared the spectroscopic redshift of 12 confirmed clusters in the field (6 clusters listed in XXL Paper XX, four from Pierre et al. 2006; Papovich et al. 2010; Willis et al. 2013; Andreon et al. 2014, and 2 others confirmed clusters in the XXL-N/VIDEO area) to the photometric redshift generated by the cluster finding procedure. Figure 4 shows the result of this comparison. At , the differences between the photometric and spectroscopic redshifts fall well within the photometric redshift error estimates. These error bars represent the standard deviation of the best-fitting Gaussian model. For the two high-redshift clusters, the photometric redshifts seem to underestimate the spectroscopic values. Therefore, we calculate the root mean square (RMS) of the and clusters separately. We obtained 0.02 and 0.14 respectively. For now on, we will use these RMS values as the uncertainties on the photometric redshifts.

3.3 Clusters estimated masses

Following a similar methodology than the second data release of XXL, we used scaling relations to provide mean parameters estimate for clusters for which the data quality is not enough to perform a direct spectral fit. A detailed description is provided in Sect. 4.3 of XXL Paper XX, and we provide a brief overview here. We estimated count-rates in the pn data in the [0.5-2] keV band within 300 kpc of the cluster centre using the Bayesian approach to fixed aperture photometry measurement outlined in Willis et al. (2018). We then converted this count-rate to the corresponding X-ray luminosity by adopting an initial gas temperature, a metallicity fixed to 0.3 times the solar value (as tabulated in Anders & Grevesse 1989), and the cluster spectroscopic (when available) or photometric redshift. With the same initial guess of the temperature, we estimate from the mass-temperature relation constrained from a subset of 105 XXL clusters that have both measured HSC lensing masses and X-ray temperatures (see Umetsu et al. 2020). We stress that here we use a relation, obtained using the Bayesian regression scheme implemented in the LIRA package (Sereno 2016; Sereno et al. 2016), and not the relation reported in Umetsu et al. (2020). The luminosity is then extrapolated from 300 kpc to assuming a -model for the cluster emissivity with parameters . Then a new temperature is evaluated using the best-fit result for the luminosity-temperature relation quoted in Table 6 of XXL Paper XX (XXL fit). The iteration on the gas temperature is stopped when the input and output values agree within 5%, and in general the process converges after 2-3 steps. The uncertainties on the derived parameters and in particular the masses, are obtained by propagation of errors on the scaling parameters, including the measured correlation among them.

3.4 Other clusters in XXL-N/VIDEO

There are 54 previously confirmed clusters either within or overlapping with the XXL-N/VIDEO field (XXL Paper XX). Of these, 47 are located at with the remaining seven clusters located at . These seven clusters correspond to a surface density of 1.6 distant clusters per square degree. This number represents a lower limit because some known clusters associated with an extended X-ray detection (e.g. JKCS 041, a z=1.803 confirmed cluster Andreon et al. 2014) are excluded of (XXL Paper XX) compilation.

Adding all our detections would bring up this number to approximately 8.2 clusters per square degree, with a flux limit of in the [0.5-2] keV band (Chen et al. 2018). This represent 3.6 times and 0.51 times the surface densities reached by Willis et al. (2013) and Finoguenov et al. (2010) respectively, with depths of and in the [0.5-2] keV band.

4 Quenching and star formation in clusters

The fraction of quenched galaxies in a sample of distant, X-ray selected galaxy clusters has the potential to provide an unbiased view of the star formation conditions in massive, virialised structures. In this section, we compute the fraction of quenched galaxies within the XXL-N/VIDEO distant cluster sample, focussing on the clusters at , because the catalogue 5 magnitude limit restricts the number of selected galaxies beyond that redshift. We achieve this employing four related analysis techniques, intending to investigate whether each provides consistent results. Only the galaxies brighter than the 5 limit in J and are used in these computations.

-

1.

The first employs the colour histogram of background corrected galaxies in the field of each candidate cluster. This colour space distribution is then modelled using two Gaussian functions to represent the red sequence and the blue cloud (see Fig. 5).

-

2.

The second method employs the same background corrected colour distribution as above but employs a single colour cut to divide the distribution into quenched and star-forming galaxies.

-

3.

The third method selects cluster galaxies using photometric redshift and then applies the boundary method used in method (2) above.

-

4.

The fourth method is similar to method (2) with the additional constraint that each galaxy (including the background) must be brighter than at the candidate cluster redshift. The evolutionary k-correction is computed using method 1 results (see Fig. 6).

4.1 First quenching method

The first step consists of defining the appropriate area within which to select field-of-view galaxies for each cluster. Some studies (e.g. Wetzel et al. 2012; Pintos-Castro et al. 2019) analyse the quenched/star-forming fraction up to several virial radii. However, since several of our fields appear to contain secondary overdensities, we choose to restrict our analysis closer to the cluster centre, namely within a radius of 1.35 Mpc around the X-ray coordinates. A radius of 1.35 Mpc corresponds to approximately 1.5 times the value of for a galaxy cluster (Chen et al. 2007) and to an angle of 2.76 arcminutes at . We further select galaxies with a photometric redshift between 0.60 and 2.04, both in the cluster field and background catalogue, and sample the resulting distributions into 0.04 wide bins in colour.

We then correct this field-of-view distribution using the same method as applied in Eq. 1. Visual inspection reveals that the resulting colour distribution is bimodal (see Fig. 5). We model this bimodal colour distribution using two Gaussian functions – one representing the red sequence and the other the blue cloud. In some fields we note that the background correction is either too large or too small to yield to a clear bimodal distribution, resulting in poor fits or even in a non-convergent fitting algorithm (candidate 7). In such cases, we adjusted the background correction by up to 20% before determining whether the adjusted background results in an improved fit. Figure 5 presents the effect of an unadjusted background on the colour distribution on two typical field. Although both the too high and too low cases are presented, the former concerns only four clusters. One of these clusters is confirmed (candidate 3) and two others (including the case presented in Fig. 5) are among the sample of other photometric studies (see Olsen et al. 2007; Wen & Han 2011; Licitra et al. 2016). Thus, most of them are unlikely to be false detections.

Three of the eight clusters with an increased background lie in overlaps between two VIDEO footprints and have thus, according to Jarvis et al. (2013) longer exposure times. Moreover, two additional clusters are in the XMM1 field, which is part of the ultra-deep layer of HSC-SPP survey and thus possess 1 to 1.5 mag deeper photometry in the i and z band (see Adams et al. 2020).

The quenched fraction is then computed as the integral of the best-fitting red sequence Gaussian profile, divided by the sum of the integrals of the blue cloud and red sequence Gaussian profiles.

Some clusters were removed from the analysis. We removed 1, 4, 10, 21, and 24 since there are indications of more than one overdensity along the line-of-sight to each of these X-ray sources. Candidate clusters at were also removed, resulting in a sample of 21 candidate clusters.

Next, we investigate whether the Gaussian modelling produces consistent average star formation histories, i.e. whether the red sequence colour can be described adequately by a simple stellar population model. We used Flexible Stellar Population Models (FSPS; see Conroy et al. 2009; Conroy & Gunn 2010; Foreman-Macke et al. 2014), modelling the red sequence stellar population with an exponentially decreasing star formation rate characterised by an -folding timescale , displaying solar metallicity and no dust. We generated a grid of models with two free parameters: we tested 100 formation redshifts between 4 and 16, and 100 values between 0.1 and 2.5 Gyr for a total of 10000 models. The model providing the best fit has a formation redshift of 16 with a characteristic time of 1.19 Gyr and a reduced , corresponding to a rejection probability of 24%. The red sequence displayed on the CMD plot in Fig. 2 is based on this model. The associated uncertainty is the standard deviation of the difference of red sequence colours, as predicted by the model, and the Gaussian modelling results. We also used this fit to compute the evolutionary and K-correction associated with the characteristic luminosity used in method 4.

4.2 Other quenching methods

The second method to identify quenched galaxies employs the same colour binning and background subtraction procedure as employed by Gaussian method described above. We specify the colour where the blue and red Gaussian models are equal as the boundary between the red sequence and the blue cloud. We further restrict the colour interval by rejecting any galaxy redder than 2.5 times the standard deviation of the red Gaussian or bluer than 2.5 times the standard deviation of the blue Gaussian. Where those boundaries fall within a colour bin we perform a fractional calculation within the affected bins.

The third method does not include the area-corrected background subtraction used in the first two methods but instead selects cluster members based on their photometric redshift. Any galaxy within the field-of-view and with a redshift consistent with the cluster mean redshift plus or minus 1.5 times its standard deviation (calculated in Sect. 2.4) is considered as a cluster member. We then selected the red sequence and blue cloud members using the colour boundaries defined in method two.

All the methods described above employ the 5 limit of the VIDEO catalogue in J and bands as a magnitude selection threshold. The fourth quenching method is essentially the same as method 2 yet with an evolving magnitude limit based upon the values of in J and bands computed using our best-fitting FSPS model for the red sequence, i.e. including both an evolutionary and -correction (see Fig. 6). As in Sect. 2.3, we assume a characteristic absolute magnitude of -22.26 at (see also Cirasuolo et al. 2010).

A comparison between method 1 and the other methods is presented in Fig. 7. Each method generates similar quenched fractions compared to method 1. Within the limited variation of the approaches taken by each method, this indicates that the quenched fractions are robust from method to method. The few clusters for which the quenched fractions obtained by method 1 are more than 1.5 times the standard deviation above or below the mean are identified and highlighted. For now on, we will focus on method 4 results.

4.3 Quenching results

Figure 6 shows the quenched fraction results of the fourth method and indicates that there is a wide variety of quenching levels within the interval . The wide range of computed quenched fractions is nominally consistent with the expectation expressed in Sect. 1 that the X-ray selection of galaxy clusters should be less biased to the properties of their member galaxies than optical/IR overdensity methods.

We next test whether, despite the range of quenched fractions, there is a consistent variation of quenched fraction as a function of cluster-centric distance within the sample of clusters as a whole. We computed the quenched fraction for each cluster within three equal radial annuli out to 1.35 Mpc. We then computed the mean cluster quenched fractions as a function of radius into two groups based upon the total quenched fraction, i.e. we stacked those clusters quenched at the level greater than the median quenched fraction into one group and those quenched at less than the median level into another.

We then investigated if the quenched fraction depends upon galaxy luminosity. We computed the quenched fraction in three bins of luminosities (0.5 to 1 , 1 to 2 , and 2 to 4 ). Once again, the results for each cluster are stacked on the basis of their overall quenching level. This test is limited to because beyond this 0.5 falls below the 5 magnitude cut.

Figure 8 displays no significant trend between the mean quenched fraction and the cluster-centric radius, especially for the highly quenched half of the sample. We note however a slight increase of the quenched fraction toward the centre of the lowly quenched cluster, suggesting a weak dependence of the quenched fraction with the distance. The bottom panels of Fig. 8 show that more luminous galaxies are more quenched, although the variation is less pronounced in highly quenched clusters.

5 Brightest cluster galaxies

To identify candidate BCGs within each galaxy cluster we noted initially that 80% of BCGs are located within 0.1 virial radii of the cluster X-ray emission peak (Lin & Mohr 2004). They are usually – but interestingly not always (e.g. Lange et al. 2018) – the most luminous galaxy in the cluster. We therefore selected galaxies within 225 kpc of the X-ray detection coordinates where this distance corresponds to approximately 15% of the virial radius of a cluster (we added an extra 5% to account for possible offsets between the X-ray best-fit model centres and the X-ray emission peaks). We then applied a luminosity cut to select galaxies brighter than 3 in J and bands (using the model computed in Sect. 4.1 to compute evolutionary effects and a full -correction). If the luminosity cut resulted in less than three candidate BCGs, we extended the cut to 2.5 . If there still remained less than three galaxies, we enlarged our search radius to 450 kpc. We implemented this three candidate limit because we noticed that some fields contained faint stars misclassified as galaxies or quasars in the VIDEO catalogue.

To identify spurious candidates we next performed a visual check of the BCG candidates, paying special attention to the brightest and second brightest candidates. We also flagged (but did not remove) candidates with unreliable photometry, such as candidates within the halo of a star or blended sources. We then created , , and colour magnitude diagrams of the central 225 kpc of each cluster to determine which candidate BCGs displayed colours consistent with the cluster redshift. This step also conferred the benefit that it identified galaxies with magnitudes and colours comparable to the 2 most luminous candidates that might have been missed by the previous cuts. We then selected up to three potential BCGs within each cluster. In most clusters considered, a single BCG candidate is prominent. In cases with more than one candidate BCG, we used the band luminosities to select the most likely BCG, followed by projected cluster-centric distance if band magnitudes were similar. When possible, we used the CESAM spectroscopic database to check the redshift of our selected BCG candidates and make adjustments in the case of obvious inconsistencies with the estimated cluster redshift.

We compared our BCG list to Wen & Han (2011), XXL Paper XV, and Ricci et al. (2018, hereafter XXL Paper XXVIII), although we have respectively only 15, 1, and 5 clusters in common. Those three studies have slightly different BCG selection criteria: Wen & Han (2011) use the i, , or the r band depending on the data available, while XXL Paper XV and XXL Paper XXVIII respectively use z and i’ band photometry as their main selection criterion. Each uses larger search radii and, in the case of XXL Paper XXVIII, a stricter photometric redshift cut.

We found the same BCGs for 11 of the 15 shared candidates with Wen & Han (2011). When our selection disagrees, Wen & Han (2011) BCG is either fainter than our selected candidate (candidates 13 and 18), possesses an incompatible spectroscopic redshift (candidate 12), or is an obvious foreground galaxy (candidate 1). For candidate 20, the only common candidate with XXL Paper XV, our BCG selection agrees. In the case of clusters in common with XXL Paper XXVIII, 4 of the 5 common clusters have matching BCGs (candidates 3, 8, 20, and 21). For candidate 2, they selected our second-best BCG candidate, which, unlike our chosen candidate, possesses a spectroscopic redshift. However, XXL Paper XXVIII preferred candidate is fainter than our chosen candidate in i, z, J, and band.

As a final step, we employed FSPS to generate a suite of stellar population models which we compared to the colours of our total sample of BCGs as a function of redshift. We tested 100 different formation redshifts between 3 and 16, in combination with 100 different metallicities between 0.1 and 5 . We assumed a instantaneous starburst, no dust extinction, and a Salpeter initial mass function (Salpeter 1955). We then tested the effect of including a third free parameter, using ten different formation redshifts and 50 metallicities within the same intervals as above. We first tested the effect of dust, with 25 dust obscuration percentages covering 0 to 99.3%, calculated as a power law with a -0.7 index. We also investigated the effect of permitting a dust-free exponentially decreasing star formation rate (SFR) employing 25 values between 0.004 and 1 Gyr.

We limited the stellar population modelling to BCGs drawn from clusters in the interval and also removed BCGs with unreliable photometry. We also excluded candidate 10 because no suitable BCG candidate was identified. We thus performed our fits with a sample of 23 BCGs. The models described above generates fits characterised by reduced (hereafter noted ) approximately equal to 3.5. The left panel of Fig. 9 presents these best fitting models and their associated confidence intervals. An examination of that Fig. indicates that the single model fits might well be averaging two groups of BCGs, namely a group with red colours and a comparatively bluer group. We will refer to these groupings as red and blue BCGs. None of the BCGs in the blue sample is bluer than the red sequence model, displayed as a magenta dotted line in Fig. 9. This discrepancy is discussed further in Sect. 6.2.

We find that none of the fitted stellar population models appears to capture the overall slope of colour versus redshift for the combined BCG sample. However, we noted with interest that the stellar population model of Lidman et al. (2012) appears to provide an effective method to segregate the red and blue BCGs. We therefore segregated the red and blue BCGs employing the colour difference with respect to the Lidman et al. (2012) model colours as a function of redshift (see Fig. 10, left panel). Having split the BCGs into red and blue on the basis of this criterion we then applied the FSPS fitting procedure described above to both populations and performed a final check of the BCG colour evolution versus redshift with respect to the best-fitting red and blue models (Fig. 10, centre and right panels). All three approaches generate the same division between red and blue BCGs.

| Fit | Dust absorptiona | Metallicity | |||

| (%) | () | (Gyr) | |||

| No dust, varying and Z | 1.140 | 14.214 | 0 | 1.44 | 0 |

| Varying , Z, and dust | 1.155 | 11.030 | 61.28 | 0.40 | 0 |

| No dust, varying , Z, and | 1.250 | 11.030 | 0 | 1.40 | 0.010 |

| a Fraction of starlight absorbed by dust. | |||||

| b Characteristic timescale for an exponentially decreasing star formation rate. | |||||

| Fit | Dust absorptiona | Metallicity | |||

| (%) | () | (Gyr) | |||

| No dust, varying and Z | 1.497 | 4.426 | 0 | 1.24 | 0 |

| Varying , Z, and dust | 1.920 | 3.613 | 6.67 | 1.10 | 0 |

| No dust, varying , Z, and | 1.954 | 5.241 | 0 | 1.20 | 0.317 |

| a Fraction of starlight absorbed by dust. | |||||

| b Characteristic timescale for an exponentially decreasing star formation rate. | |||||

Treating the red and blue BCGs as separate populations provides a significant improvement to the quality of the stellar population fits (see Fig. 9, middle and right panels).

Tables 2 and 3 give the and best parameter fits for every model tested. The uncertainties are based on the 1 photometry errors. Despite relatively good (1.140 for the simplest model), none of the red BCG fits seem able to capture the slope of the J- colours of the high-redshift half of the the sample. Both the simple and dusty models perform similarly, but the plausibility of the latter seems questionable, since it features a starlight dust absorption percentage of 61%.

For the blue BCGs, there is no visible slope discrepancy between the data and the model. However, the are larger than in the red BCGs case, probably because none of the applied models include a term for intrinsic scatter. In fact, the 95% confidence interval of the simplest model (which has also the minimum ) is barely spawning the variety of colours observed in the blue BCGs. This may indicates that the blue BCG population is too diverse to be represented by a single stellar population model.

| # | Candidate name | BCG RA & Dec | z | BCG stellar masses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (degrees) | () | |||

| 1 | 3XLSS J022222.9-044043 | 35.5854 -4.6857 | 0.80a | |

| 2 | XLSSC 184 | 35.3169 -4.2079 | 0.81 | |

| 3 | XLSSC 071 | 35.6420 -4.9655 | 0.83 | |

| 4 | 3XLSS J022432.9-044742 | 36.1398 -4.7940 | 0.83a | |

| 5 | 3XLSS J022135.2-051811 | 35.3985 -5.3052 | 0.84 | |

| 6 | XLSSU J021947.4-050841 | 34.9458 -5.1399 | 0.86a | |

| 7 | XLSSC 15 | 35.9273 -5.0336 | 0.86 | |

| 9 | 3XLSS J022557.1-042845 | 36.4802 -4.4804 | 0.90a | |

| 11 | 3XLSS J021945.5-044831 | 34.9362 -4.8124 | 0.91a | |

| 12 | XLSSU J022530.3-042544 | 36.3738 -4.4295 | 0.92 | |

| 13 | 3XLSS J022804.6-045351 | 37.0203 -4.9056 | 0.93a | |

| 14 | XLSSU J022051.0-050958 | 35.2108 -5.1620 | 0.97a | |

| 15 | 3XLSS J022103.0-045524 | 35.2634 -4.9222 | 0.97a | |

| 16 | 3XLSS J022739.0-045830 | 36.9073 -4.9698 | 0.99a | |

| 18 | XLSSC 044 | 36.1345 -4.2287 | 1.00a | |

| 20 | XLSSC 029 | 36.0175 -4.2240 | 1.05 | |

| a Photometric redshift. The uncertainties are . | ||||

| # | Candidate name | BCG RA & Dec | z | BCG stellar masses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (degrees) | () | |||

| 8 | XLSSC 064 | 34.6335 -5.0165 | 0.87 | |

| 17 | 3XLSS J022044.7-041713 | 35.1953 -4.2900 | 1.00a | |

| 19 | XLSSC 124 | 34.4272 -4.8658 | 1.00a | |

| 21 | XLSSC 005 | 36.7872 -4.2988 | 1.06 | |

| 23 | 3XLSS J022027.0-043538 | 35.1173 -4.6041 | 1.09a | |

| 25 | XLSSC 141 | 34.3478 -4.6696 | 1.21a | |

| 26 | XLSSC 046 | 35.7636 -4.6043 | 1.21 | |

| a Photometric redshift. The uncertainties are . | ||||

Nevertheless, we computed the BCG stellar masses for the red and the blue BCGs, using the parameters from the simple model (i.e the instantaneous starburst model with no dust). We adopt a similar approach than Lidman et al. (2012), computing the mass as the quotient between the observed and the modelled flux density in band, correcting with the model stellar mass. To estimate the uncertainties, we computed the band fluxes of every model enclosed in the 68% confidence region. We then take their standard deviation as the uncertainty on the flux and propagated this error to the mass.

Results are presented in Tables 4 and 5. The mean masses are and for the red and blue BCGs respectively.

6 Discussion

6.1 Cluster quenched fractions

Figure 7 presents a wide variety of quenched fractions, with no clear trend, despite that, at higher redshifts, only the most luminous (massive) galaxies are visible. The fourth method of computing the quenched fraction incorporates a luminosity cut specifically intended to mitigate this bias. However, although this method generates slightly higher quenched fractions (except for the two lowest redshift clusters in our sample; see Fig. 7), it does not otherwise affect the apparent diversity of quenched fractions. There is thus no evidence of evolution with redshift in Fig. 6.

The results presented in Sect. 4.3 demonstrate a link between quenched fraction and the band luminosity, although the link seems weaker for the highly quenched half of our sample. band luminosities are a proxy for galaxy stellar masses (assuming dust extinction is negligible). Such a link has been observed before (e.g. Peng et al. 2010, 2012; Muzzin et al. 2012; Balogh et al. 2016; Kawinwanichakij et al. 2017; Jian et al. 2018; Pintos-Castro et al. 2019), although whether this is due to mass-dependent galaxy evolution and/or to environment remains an open question.

We observe no significant evidence that the quenching fraction varies with the cluster-centric distance, although the quenched fraction is slightly higher toward the centre of the lowly quenched clusters in our sample – an observation in agreement with previous studies (e.g. Muzzin et al. 2012; Pintos-Castro et al. 2019). The more quenched half of our sample possesses levels of quenching above 70% in all bins, which might be because only galaxies above are included in this profile and that bright galaxies tend to be slightly more quenched at all radii.

6.2 A bimodal Brightest Cluster Galaxy population?

The colours of the candidate BCGs in the distant cluster sample are not consistent with the properties of a single, passively-evolving stellar population. There is tentative evidence for a bimodal distribution of BCG colours. Separating the sample employing the fiducial stellar population model of Lidman et al. (2012), we find that the colours of the redder BCGs in our sample are consistent with an older, instantaneous burst of metal-rich stars whereas the bluer BCG colours are more diverse and possibly related to a younger component in the stellar population.

Despite this variety of colours, only one of the BCGs is bluer than the red sequence model computed in Sect. 4.1 (see also Fig. 9). This might indicate that BCG stellar populations have different properties (such as metallicity) than the average quenched galaxies in cluster, as suggested by some low-redshift studies (e.g. Von Der Linden et al. 2007; Loubser et al. 2009).

Figure 11 shows the degeneracy between metallicity and formation redshift as applied to the stellar population models describing the two BCG samples. We observe that the 98% confidence regions of the two BCG samples do not overlap, supporting the idea that the stellar populations of the blue and red BCGs are indeed different. The confidence intervals for the blue sample are centred on lower metallicities than the red sample regions while formation redshift also tends to be lower – although the confidence regions of both models extend over a wide range of redshifts.

Based on the stellar population analysis, one might infer that blue BCGs have formed more recently than the red ones. However, Li & Han (2007) report that when more than one stellar population is present, the age and metallicity obtained by colours alone might be biased toward the younger and more metal-rich stars. Therefore, the blue BCGs might be bluer because they have experienced either an extended star formation episode or more than one bursts in the past. In such scenarios, differences in the duration of the star formation or in the relative importances and epochs of the secondary bursts would account for the spread in colour observed in the bluer BCGs.

One factor that may trigger a star formation episode is a cooling flow. Several studies have reported the existence of blue, moderately star-forming BCGs in cool core clusters at low to moderate redshifts (e.g. Egami et al. 2006; Bildfell et al. 2008; Stott et al. 2008; Loubser et al. 2009, 2016; Pipino et al. 2009; Rawle et al. 2012; Green et al. 2016). Since X-ray selected clusters are biased toward relaxed clusters (Rossetti et al. 2017), this might partially explain why the blue BCGs represent a significant part of our sample.

Alternatively, statistical studies based on infrared (e.g. Webb et al. 2015; Bonaventura et al. 2017) or SZ-selected clusters (e.g. McDonald et al. 2016) have shown that in-situ star formation is an important mechanism at , possibly triggered by galaxy interactions (McDonald et al. 2016). This suggests that a range of BCG colours might be part of every high-redshift sample, regardless of the sample selection.

One limitation of the current analysis is that the fitted stellar population models are unable to accommodate the slope of the high-redshift end of the red sample J- colour variation with redshift (see Fig. 9) and that no BCGs are red beyond . This suggest that the stars making up the red BCGs formed later or evolve faster than predicted by our model. The former is supported by the degeneracy between formation redshift and metallicity. The best-fitting formation redshift, , might be considered high compared with the predictions of the most recent simulations (e.g. Ragone-Figueroa et al. 2018; Rennehan et al. 2020), but – alternatively – consistent with recent observations (Hashimoto et al. 2018; Willis et al. 2020).

Dust extinction might be evoked to explain why these objects are so red. Indeed, a fit including dust provides an equivalent statistical description of the red BCGs (see Table 2), although we note that the colour of a model stellar population is degenerate between star formation history, metallicity, and dust obscuration. For this reason, we prefer a simple, dust free model for the analysis of the red BCG population.

Ultimately, the current data available for the BCGs sample are unable to provide a definitive explanation of the blue/red dichotomy. The acquisition of rest-frame optical spectroscopy of several BCGs of both groups is needed in order to get a more accurate and thorough picture of the star formation history of these objects (e.g. Lonoce et al. 2015, 2020; Belli et al. 2017; Saracco et al. 2019).

7 Summary

We have identified a sample of 35 X-ray-selected distant galaxy clusters in the XXL-N/VIDEO field and performed a preliminary analysis of their galaxy populations. Clusters are selected as extended X-ray sources (C1, C2, or AC) coincident with overdensities of bright galaxies in photometric redshift space. Of the 35 candidate clusters at , ten are spectroscopically confirmed clusters, and a further 15 are presented here for the first time. The ten remaining clusters have been detected previously but never confirmed.

The sample of clusters displays a wide variety of quenched fractions, a result nominally consistent with the assertion made in Sect. 1 that selecting clusters on the ICM properties is insensitive to the star formation history of their member galaxies. The relationship between galaxy luminosity and quenched fraction appears to be in place at although we do not observe a significant variation of the quenched fraction with the cluster-centric radius.

The sample of BCGs is inconsistent with a single stellar population model. The observed distribution is bimodal in colour and is consistent with an old, passive population and a possibly younger,relatively bluer, and more diverse population. Although we are unable to provide a definite explanation for this split, we suggest that the blue BCGs may have experienced either an extended or more than one star-formation episode.

Acknowledgements

AT is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Postgraduate Scholarship-Doctoral Program. JPW acknowledges support from the NSERC Discovery Grant program. The Saclay group acknowledges long-term support from the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES). This work was supported by the Programme National Cosmology et Galaxies (PNCG) of CNRS/INSU with INP and IN2P3, co-funded by CEA and CNES. NA acknowledges funding from the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) Grant Code ST/R505006/1. RAAB is supported by the Glasstone Foundation, MJJ and RAAB acknowledge support from the Oxford Hintze Centre for Astrophysical Surveys which is funded through generous support from the Hintze Family Charitable Foundation and the award of the STFC consolidated grant (ST/N000919/1). XXL is an international project based around an XMM Very Large Programme surveying two 25 extragalactic fields at a depth of in the [0.5-2] keV band for point-like sources. The XXL website is http://irfu.cea.fr/xxl. Multi-band information and spectroscopic follow-up of the X-ray sources are obtained through a number of survey programmes, summarised at http://xxlmultiwave.pbworks.com/. This work is based on data products from observations made with ESO Telescopes at the La Silla Paranal Observatory under ESO programme ID 179.A- 2006 and on data products produced by the Cambridge Astronomy Survey Unit on behalf of the VIDEO consortium. This research has made use of the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED), which is funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and operated by the California Institute of Technology.

References

- Adami et al. (2018) Adami, C., Giles, P., Koulouridis, E., et al. 2018, A&A, 620, A5, (XXL Paper XX)

- Adams et al. (2020) Adams, N. J., Bowler, R. A. A., Jarvis, M. J., et al. 2020, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 494, 1771, arXiv: 1912.01626

- Aihara et al. (2018a) Aihara, H., Arimoto, N., Armstrong, R., et al. 2018a, Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan, 70, S4

- Aihara et al. (2018b) Aihara, H., Armstrong, R., Bickerton, S., et al. 2018b, Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan, 70, S8

- Alberts et al. (2014) Alberts, S., Pope, A., Brodwin, M., et al. 2014, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 437, 437

- Anders & Grevesse (1989) Anders, E. & Grevesse, N. 1989, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 53, 197

- Andreon et al. (2014) Andreon, S., Newman, A. B., Trinchieri, G., et al. 2014, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 565, A120

- Balogh & McGee (2010) Balogh, M. L. & McGee, S. L. 2010, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 402, L59

- Balogh et al. (2016) Balogh, M. L., McGee, S. L., Mok, A., et al. 2016, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 456, 4364

- Belli et al. (2017) Belli, S., Genzel, R., Förster Schreiber, N. M., et al. 2017, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 841, L6

- Bellstedt et al. (2016) Bellstedt, S., Lidman, C., Muzzin, A., et al. 2016, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 460, 2862

- Best et al. (2007) Best, P. N., von der Linden, A., Kauffmann, G., Heckman, T. M., & Kaiser, C. R. 2007, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 379, 894

- Bildfell et al. (2008) Bildfell, C., Hoekstra, H., Babul, A., & Mahdavi, A. 2008, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 389, 1637

- Bleem et al. (2015) Bleem, L. E., Stalder, B., de Haan, T., et al. 2015, The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 216, 27

- Bonaventura et al. (2017) Bonaventura, N. R., Webb, T. M. A., Muzzin, A., et al. 2017, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 469, 1259, arXiv: 1704.02721

- Brodwin et al. (2013) Brodwin, M., Stanford, S. A., Gonzalez, A. H., et al. 2013, The Astrophysical Journal, 779, 138

- Bruzual & Charlot (2003) Bruzual, G. & Charlot, S. 2003, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 344, 1000

- Böhringer et al. (2001) Böhringer, H., Schuecker, P., Guzzo, L., et al. 2001, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 369, 826

- Calzetti et al. (2000) Calzetti, D., Armus, L., Bohlin, R. C., et al. 2000, The Astrophysical Journal, 533, 682

- Carlstrom et al. (2002) Carlstrom, J. E., Holder, G. P., & Reese, E. D. 2002, Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 40, 643

- Chen et al. (2018) Chen, C.-T. J., Brandt, W. N., Luo, B., et al. 2018, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 478, 2132

- Chen et al. (2007) Chen, Y., Reiprich, T. H., Böhringer, H., Ikebe, Y., & Zhang, Y.-Y. 2007, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 466, 805

- Chiappetti et al. (2018) Chiappetti, L., Fotopoulou, S., Lidman, C., et al. 2018, A&A, 620, A12, (XXL Paper XXVII)

- Cirasuolo et al. (2010) Cirasuolo, M., McLure, R. J., Dunlop, J. S., et al. 2010, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 401, 1166

- Clerc et al. (2012) Clerc, N., Sadibekova, T., Pierre, M., et al. 2012, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 423, 3561

- Conroy & Gunn (2010) Conroy, C. & Gunn, J. E. 2010, The Astrophysical Journal, 712, 833

- Conroy et al. (2009) Conroy, C., Gunn, J. E., & White, M. 2009, The Astrophysical Journal, 699, 486

- Croton et al. (2006) Croton, D. J., Springel, V., White, S. D. M., et al. 2006, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 365, 11

- De Lucia & Blaizot (2007) De Lucia, G. & Blaizot, J. 2007, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 375, 2

- Donahue et al. (2002) Donahue, M., Scharf, C. A., Mack, J., et al. 2002, The Astrophysical Journal, 569, 689

- Dressler (1978) Dressler, A. 1978, The Astrophysical Journal, 223, 765

- Durret et al. (2011) Durret, F., Adami, C., Cappi, A., et al. 2011, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 535, A65

- Eckert et al. (2011) Eckert, D., Molendi, S., & Paltani, S. 2011, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 526, A79

- Edwards et al. (2020) Edwards, L. O. V., Salinas, M., Stanley, S., et al. 2020, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 491, 2617

- Egami et al. (2006) Egami, E., Misselt, K. A., Rieke, G. H., et al. 2006, The Astrophysical Journal, 647, 922

- Euclid Collaboration et al. (2019) Euclid Collaboration, Adam, R., Vannier, M., et al. 2019, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 627, A23

- Faccioli et al. (2018) Faccioli, L., Pacaud, F., Sauvageot, J.-L., et al. 2018, A&A, 620, A9, (XXL Paper XXIV)

- Finoguenov et al. (2010) Finoguenov, A., Watson, M. G., Tanaka, M., et al. 2010, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 403, 2063

- Foltz et al. (2018) Foltz, R., Wilson, G., Muzzin, A., et al. 2018, ApJ, 866, 136

- Foreman-Macke et al. (2014) Foreman-Macke, D., Sick, J., & Johnson, B. 2014, python-fsps: Python bindings to FSPS (v0.1.1)

- Gioia et al. (1990) Gioia, I. M., Maccacaro, T., Schild, R. E., et al. 1990, The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 72, 567

- Gladders & Yee (2000) Gladders, M. D. & Yee, H. K. C. 2000, The Astronomical Journal, 120, 2148

- Gladders & Yee (2005) Gladders, M. D. & Yee, H. K. C. 2005, The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 157, 1

- Green et al. (2016) Green, T. S., Edge, A. C., Stott, J. P., et al. 2016, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 461, 560

- Gursky et al. (1972) Gursky, H., Solinger, A., Kellogg, E. M., et al. 1972, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 173, L99

- Hashimoto et al. (2018) Hashimoto, T., Laporte, N., Mawatari, K., et al. 2018, Nature, 557, 392, arXiv: 1805.05966

- Hinshaw et al. (2013) Hinshaw, G., Larson, D., Komatsu, E., et al. 2013, The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 208, 19

- Ilbert et al. (2006) Ilbert, O., Arnouts, S., McCracken, H. J., et al. 2006, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 457, 841

- Ilbert et al. (2009) Ilbert, O., Capak, P., Salvato, M., et al. 2009, The Astrophysical Journal, 690, 1236

- Jaffé et al. (2018) Jaffé, Y. L., Poggianti, B. M., Moretti, A., et al. 2018, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 476, 4753

- Jarvis et al. (2013) Jarvis, M. J., Bonfield, D. G., Bruce, V. A., et al. 2013, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 428, 1281

- Jian et al. (2018) Jian, H.-Y., Lin, L., Oguri, M., et al. 2018, Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan, 70, S23

- Kawinwanichakij et al. (2017) Kawinwanichakij, L., Papovich, C., Quadri, R. F., et al. 2017, The Astrophysical Journal, 847, 134

- Lange et al. (2018) Lange, J. U., van den Bosch, F. C., Hearin, A., et al. 2018, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 473, 2830

- Lavoie et al. (2016) Lavoie, S., Willis, J. P., Démoclès, J., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 462, 4141, (XXL Paper XV)

- Li & Han (2007) Li, Z. & Han, Z. 2007, A&A, 471, 795

- Licitra et al. (2016) Licitra, R., Mei, S., Raichoor, A., Erben, T., & Hildebrandt, H. 2016, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 455, 3020

- Lidman et al. (2012) Lidman, C., Suherli, J., Muzzin, A., et al. 2012, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 427, 550

- Lin & Mohr (2004) Lin, Y.-T. & Mohr, J. J. 2004, The Astrophysical Journal, 617, 879

- Lonoce et al. (2015) Lonoce, I., Longhetti, M., Maraston, C., et al. 2015, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 454, 3912

- Lonoce et al. (2020) Lonoce, I., Maraston, C., Thomas, D., et al. 2020, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 492, 326

- Loubser et al. (2016) Loubser, S. I., Babul, A., Hoekstra, H., et al. 2016, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 456, 1565, arXiv: 1511.07884

- Loubser et al. (2009) Loubser, S. I., Sánchez-Blázquez, P., Sansom, A. E., & Soechting, I. K. 2009, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 398, 133

- Madau (1995) Madau, P. 1995, The Astrophysical Journal, 441, 18

- McDonald et al. (2016) McDonald, M., Stalder, B., Bayliss, M., et al. 2016, The Astrophysical Journal, 817, 86

- Muzzin et al. (2012) Muzzin, A., Wilson, G., Yee, H. K. C., et al. 2012, The Astrophysical Journal, 746, 188

- Nantais et al. (2017) Nantais, J. B., Muzzin, A., van der Burg, R. F. J., et al. 2017, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 465, L104

- Oemler (1976) Oemler, Jr., A. 1976, The Astrophysical Journal, 209, 693

- Olsen et al. (2007) Olsen, L. F., Benoist, C., Cappi, A., et al. 2007, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 461, 81

- Pacaud et al. (2006) Pacaud, F., Pierre, M., Refregier, A., et al. 2006, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 372, 578

- Papovich et al. (2010) Papovich, C., Momcheva, I., Willmer, C. N. A., et al. 2010, The Astrophysical Journal, 716, 1503

- Peng et al. (2010) Peng, Y.-j., Lilly, S. J., Kovač, K., et al. 2010, The Astrophysical Journal, 721, 193

- Peng et al. (2012) Peng, Y.-j., Lilly, S. J., Renzini, A., & Carollo, M. 2012, The Astrophysical Journal, 757, 4

- Pierre et al. (2012) Pierre, M., Clerc, N., Maughan, B., et al. 2012, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 540, A4

- Pierre et al. (2016) Pierre, M., Pacaud, F., Adami, C., et al. 2016, A&A, 592, A1, (XXL Paper I)

- Pierre et al. (2006) Pierre, M., Pacaud, F., Duc, P.-A., et al. 2006, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 372, 591

- Pierre et al. (2004) Pierre, M., Valtchanov, I., Altieri, B., et al. 2004, Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2004, 011, arXiv: astro-ph/0305191

- Pintos-Castro et al. (2019) Pintos-Castro, I., Yee, H. K. C., Muzzin, A., Old, L., & Wilson, G. 2019, ApJ, 876, 40, arXiv: 1904.00023

- Pipino et al. (2009) Pipino, A., Kaviraj, S., Bildfell, C., et al. 2009, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 395, 462

- Plionis et al. (2008) Plionis, M., López-Cruz, O., & Hughes, D., eds. 2008, A pan-chromatic view of clusters of galaxies and the large-scale structure, Lecture notes in physics, 740 (Dordrecht: Springer)

- Poggianti et al. (2004) Poggianti, B. M., Bridges, T. J., Komiyama, Y., et al. 2004, The Astrophysical Journal, 601, 197

- Poggianti et al. (2008) Poggianti, B. M., Desai, V., Finn, R., et al. 2008, The Astrophysical Journal, 684, 888

- Poggianti et al. (2016) Poggianti, B. M., Fasano, G., Omizzolo, A., et al. 2016, The Astronomical Journal, 151, 78

- Poggianti et al. (2019) Poggianti, B. M., Gullieuszik, M., Tonnesen, S., et al. 2019, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 482, 4466

- Polletta et al. (2007) Polletta, M., Tajer, M., Maraschi, L., et al. 2007, The Astrophysical Journal, 663, 81

- Postman et al. (1996) Postman, M., Lubin, L. M., Gunn, J. E., et al. 1996, The Astronomical Journal, 111, 615

- Ragone-Figueroa et al. (2018) Ragone-Figueroa, C., Granato, G. L., Ferraro, M. E., et al. 2018, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 479, 1125

- Rawle et al. (2012) Rawle, T. D., Edge, A. C., Egami, E., et al. 2012, The Astrophysical Journal, 747, 29

- Rennehan et al. (2020) Rennehan, D., Babul, A., Hayward, C. C., et al. 2020, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

- Ricci et al. (2018) Ricci, M., Benoist, C., Maurogordato, S., et al. 2018, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 620, A13, (XXL Paper XXVIII)

- Rossetti et al. (2017) Rossetti, M., Gastaldello, F., Eckert, D., et al. 2017, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 468, 1917

- Rossetti et al. (2016) Rossetti, M., Gastaldello, F., Ferioli, G., et al. 2016, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 457, 4515

- Sadibekova et al. (2014) Sadibekova, T., Pierre, M., Clerc, N., et al. 2014, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 571, A87

- Salpeter (1955) Salpeter, E. E. 1955, The Astrophysical Journal, 121, 161

- Saracco et al. (2019) Saracco, P., La Barbera, F., Gargiulo, A., et al. 2019, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 484, 2281

- Sarazin (1986) Sarazin, C. L. 1986, Rev. Mod. Phys., 58, 1

- Sereno (2016) Sereno, M. 2016, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 455, 2149

- Sereno et al. (2016) Sereno, M., Fedeli, C., & Moscardini, L. 2016, Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 01, 042

- Stott et al. (2011) Stott, J. P., Collins, C. A., Burke, C., Hamilton-Morris, V., & Smith, G. P. 2011, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 414, 445

- Stott et al. (2008) Stott, J. P., Edge, A. C., Smith, G. P., Swinbank, A. M., & Ebeling, H. 2008, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 384, 1502

- Strazzullo et al. (2013) Strazzullo, V., Gobat, R., Daddi, E., et al. 2013, The Astrophysical Journal, 772, 118

- Strazzullo et al. (2019) Strazzullo, V., Pannella, M., Mohr, J. J., et al. 2019, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 622, A117

- Sunyaev & Zel’dovich (1980a) Sunyaev, R. A. & Zel’dovich, I. B. 1980a, Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 18, 537

- Sunyaev & Zel’dovich (1980b) Sunyaev, R. A. & Zel’dovich, I. B. 1980b, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 190, 413

- Sunyaev & Zel’dovich (1970) Sunyaev, R. A. & Zel’dovich, Y. B. 1970, Comments on Astrophysics and Space Physics, 2, 66

- Sunyaev & Zel’dovich (1972) Sunyaev, R. A. & Zel’dovich, Y. B. 1972, Comments on Astrophysics and Space Physics, 4, 173

- Tonnesen (2019) Tonnesen, S. 2019, The Astrophysical Journal, 874, 161

- Tremaine & Richstone (1977) Tremaine, S. D. & Richstone, D. O. 1977, The Astrophysical Journal, 212, 311

- Umetsu et al. (2020) Umetsu, K., Sereno, M., Lieu, M., et al. 2020, The Astrophysical Journal, 890, 148

- Vikhlinin et al. (1998) Vikhlinin, A., McNamara, B. R., Forman, W., et al. 1998, The Astrophysical Journal, 502, 558

- Von Der Linden et al. (2007) Von Der Linden, A., Best, P. N., Kauffmann, G., & White, S. D. M. 2007, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 379, 867

- Webb et al. (2015) Webb, T. M. A., Muzzin, A., Noble, A., et al. 2015, The Astrophysical Journal, 814, 96

- Wen & Han (2011) Wen, Z. L. & Han, J. L. 2011, The Astrophysical Journal, 734, 68

- Wetzel et al. (2012) Wetzel, A. R., Tinker, J. L., & Conroy, C. 2012, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 424, 232

- Willis et al. (2020) Willis, J. P., Canning, R. E. A., Noordeh, E. S., et al. 2020, Nature, 577, 39

- Willis et al. (2013) Willis, J. P., Clerc, N., Bremer, M. N., et al. 2013, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 430, 134

- Willis et al. (2018) Willis, J. P., Ramos-Ceja, M. E., Muzzin, A., et al. 2018, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, arXiv: 1804.06475

- Wilson et al. (2006) Wilson, G., Muzzin, A., Lacy, M., et al. 2006, arXiv:astro-ph/0604289, arXiv: astro-ph/0604289

- Wilson et al. (2009) Wilson, G., Muzzin, A., Yee, H. K. C., et al. 2009, The Astrophysical Journal, 698, 1943

- Zel’dovich & Sunyaev (1969) Zel’dovich, Y. B. & Sunyaev, R. A. 1969, Astrophysics and Space Science, 4, 301

Appendix A Notes on individual objects

Candidates 1 and 24

Candidate 1/24 was observed by Gemini South in 2010 and classified as a distant cluster (John Stott, personal communication), but, to our knowledge, the results were never published. We observed two spikes in the photometric redshift space of this source, one at and one at . Furthermore, the X-ray emission associated with this detection is complex with several brighter spots. This suggest that there might be two distant clusters in the same line-of-sight.

Candidate 5

The BCG of this cluster has a possible companion 0.454 magnitudes less luminous in band. The optical centre of both galaxies lie at a projected separation of 58.2 kpc (7.48 arcsec). The projected separation between the BCG and the X-ray coordinates is 27.4 kpc and 43.6 kpc for the companion. Neither the BCG nor the companion exhibit signs of interactions. We were able to confirm this cluster with archival spectroscopic observations stored in the CESAM database (XXL Paper XX).

Candidates 6 and 27

Both candidates 6 and 27 are faint detection in the vicinity of bright point sources. Thus, in these two fields, we increased the number of X-ray contours from 10 to 25. Candidate 6 is at and candidate 27 is at .

Candidate 10

Despite appearing as an isolated spike in the redshift space, candidate 10 seems to be constituted of two or more overdensities: the background subtracted colour diagram of candidate 10 exhibit four ‘bumps’ rather than two. Similarly, none of our BCG candidates seems reliable: the best one exhibit a very red J- colour, more consistent with than and indeed has photometric redshift of . The two other BCGs candidates both sit at more than 750 kpc of projected separation with the X-ray coordinates. Since candidate 10 meets our detection criteria, we included it in our list of candidate clusters, but not in our analysis.

Candidate 30

Candidate 30 has a photometric redshift of which make it one of our newly discovered very high-z cluster. Unfortunately, the photometry of the BCG and of another central galaxy are unreliable because they are in the halo of a foreground star.

Candidate 33

Among the candidate clusters presented here for the first time, candidate 33 is probably the second most distant one, with a photometric redshift of . This is again a robust (significance between 4.5 and 5.5 galaxies) detection in the photometric space. X-ray emission is regular, and the distance between its coordinates and the BCG is 60.8 kpc. The BCG is extremely red: its Z-J and J- colours are 2.45 and 1.59 respectively while the mean colours of the others BCGs with reliable photometry (i.e. excluding candidate 31) are 1.45 and 0.90. Interestingly, the i-z colour discrepancy between candidate 33 and the other high-z BCGs is smaller in i-z: 0.88 for candidate 33 compared to 0.63. Such colours might originate from the presence of dust in this object, but more data are needed to confirm.

Candidate 35

This candidate cluster is probably the farthest object in our sample, with a photometric redshift of . This X-ray detection is associated with multiple spikes in the photometric redshift space. Since the photometric redshift does not perform very well at , some of these spikes might be associated with the main overdensity. However the presence of a significant spike at suggests the presence of at least another overdensity along the line-of-sight.

Other candidate clusters at

There are four other new candidate clusters at in our sample: candidates 28, 29, 31, and 32 sitting at redshifts of , , , and . Candidate 32 is a weaker X-ray detection than the 3 others but also features the most significant photometric redshift spike.