Strong odd coloring of sparse graphs

Abstract

An odd coloring of a graph is a proper coloring of such that for every non-isolated vertex , there is a color appearing an odd number of times in . Odd coloring of graphs was studied intensively in recent few years. In this paper, we introduce the notion of a strong odd coloring, as not only a strengthened version of odd coloring, but also a relaxation of square coloring. A strong odd coloring of a graph is a proper coloring of such that for every non-isolated vertex , if a color appears in , then it appears an odd number of times in . We denote by the smallest integer such that admits a strong odd coloring with colors. We prove that if is a graph with , then , and the bound is tight. We also prove that if is a graph with and , then .

1 Introduction

All graphs in this paper are finite. Let be a graph. For a vertex , let be the degree of , be the neighborhood of , and . Also, is the maximum degree of . The girth of is the length of a shortest cycle in and the maximum average degree of is the maximum of over all non-empty subgraphs of .

For a positive integer , a proper -coloring of a graph is a function from the vertex set to such that adjacent vertices receive different colors. The minimum for which a graph has a proper -coloring is the chromatic number of . A square coloring of a graph is a proper coloring of , where is the graph obtained from by adding edges joining vertices at distance at most in . In 1977, Wegner conjectured the bound for when is planar.

Conjecture 1.1 ([24]).

Let be a planar graph. Then

Thomassen[22] and Hartke et al.[17] independently proved Conjecture 1.1 when , and it has attracted many researchers to study square coloring problems (see [1, 16, 18, 8, 5, 4, 13, 14, 12, 3] and Table 1 for some results on planar graphs).

The concept of odd coloring was introduced by Petruševski and Škrekovski [21] as not only a strengthening of proper coloring and but also a weakening of square coloring. For a positive integer , an odd -coloring of a graph is a proper -coloring of such that every non-isolated vertex has a color appearing an odd number of times in . The minimum for which has an odd -coloring is the odd chromatic number of , denoted by . Ever since the first paper by Petruševski and Škrekovski [21] appeared, there have been numerous papers [6, 7, 10, 15, 19, 20, 23, 9] studying various aspects of this new coloring concept across several graph classes. Recently, Dai, Ouyang, and Pirot [11] introduced a strengthening of odd coloring. For positive integers and , an -odd -coloring is a proper -coloring of a graph such that every vertex has colors each of which appears an odd number of times in . The is the minimum for which has an -odd -coloring. It is clear that by definitions.

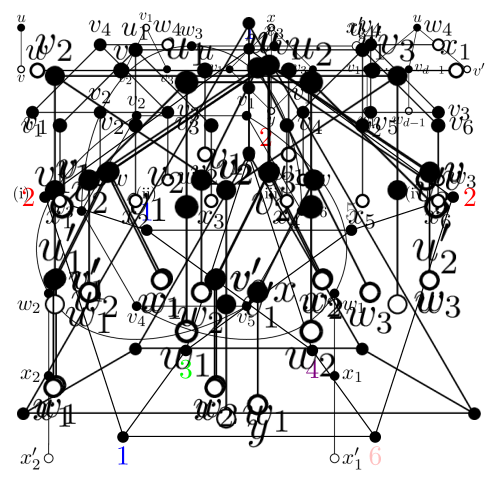

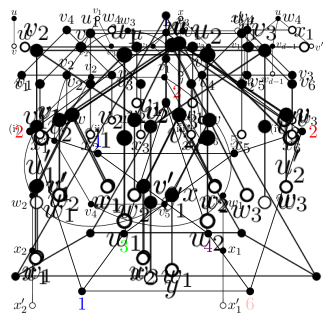

In this paper, we introduce a new concept that is a new generalization of odd coloring. For a positive integer , a strong odd -coloring (an SO -coloring for short) of a graph is a proper -coloring of such that for every non-isolated vertex , if a color appears in , then it appears an odd number of times in . The strong odd chromatic number of a graph , denoted by , is the minimum such that has an SO -coloring. See Figure 1 for an example. Like as odd coloring, strong odd coloring does not have hereditary, that is, there are graphs and such that and .

Every graph has a strong odd coloring since a square coloring is also a strong odd coloring. Moreover, it is clear from the definitions that for every graph ,

When is claw-free, that is, has no as an induced subgraph, it holds that . However, could be arbitrary large. For example, if , then and . We remark that whereas by [6], a linear bound of in terms of cannot be obtained in general. For example, if , then , the diameter of is two, and is claw-free, and thus .

Regarding to subcubic planar graphs , we have , the bound is tight since there is a subcubic planar graph such that . For a graph in Figure 2, it has maximum average degree , and which is a tight example in the following our main result.

Theorem 1.2.

If is a graph with , then .

In [18], it was shown that if is a graph with and and therefore, we have the same bound for . We improve this as follows.

Theorem 1.3.

If is a graph with and , then .

When , we obtain the same result as long as has no -cycle as a subgraph.

Theorem 1.4.

If is a -free subcubic graph with , then .

Since for every planar graph , we obtain the following corollary from Theorems 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4. See also Table 1 to compare the results on square coloring of planar graphs with large maximum degree and large girth.

Corollary 1.5.

Let be a planar graph.

-

(i)

If , then .

-

(ii)

If , then .

2 Preliminaries

For , let denote the graph obtained from by deleting the vertices in . If , then denote by . For a positive integer , we use -vertex (resp. -vertex and -vertex) to denote a vertex of degree (resp. at least and at most ). We also use -neighbor (resp. -neighbor and -neighbor) of a vertex to denote a -vertex (resp. -vertex and -vertex) that is a neighbor of . For positive integers and , we call a -vertex with at least -neighbors a -vertex. We also use -neighbor of a vertex to call a neighbor of that is a -vertex.

For an integer , let be nonempty sets. A sequence is called a system of odd representative for if it satisfies the following:

-

(i)

for each , and

-

(ii)

if for some , then appears an odd number of times in .

Lemma 2.1.

For an integer , let be nonempty subsets of size at least . Then for every , there is a system of odd representative for .

Proof.

It is enough to assume that for each . Fix . Then we define a loopless multigraph with and . Note that it is sufficient to find an orientation of such that is even and is either odd or for every , by taking the head of the arc of as a representative of for each .

To find such orientation of , we will find an ordering of the vertices of as follows. Let . If , then take any vertex in as . If , then we take and then choose an edge joining and . Let be the set of such chosen edges , and note that induces a linear forest of .

For simplicity, let be the spanning subgraph of induced by for each . We will define an orientation of for each , as follows. First, we define an orientation of by . Suppose that is defined. If , then we define . If , then , and so we define so that , where

It remains to show is a desired orientation, that is, satisfying the condition that is even and is either odd or for every . Take a vertex . Suppose that the edge exists. By the definition of ,

Hence it satisfies the condition. Suppose that the edge does not exist. If , then and so . If , then , and so it always holds that . Hence, it completes the proof. ∎

Throughout this paper, we use to denote the set of all colors, when we consider a -coloring of a graph . For a (partial) coloring of a graph , let for .

In each proof of following lemmas, we will start a proof with defining a nonempty subset . We always let , , and be an SO -coloring of , if it exists. We also define

We call an element of an available color of under . Note that

| (2.1) |

When we color the vertices of for some , we often use the same symbol to denote the resulting coloring, that is a coloring of .

Lemma 2.2.

For an integer , let be a minimal graph with respect to such that has no SO -coloring, where . For a -vertex , there is no SO -coloring of such that there is an available color of under and the neighbors of get distinct colors.

Proof.

Suppose that such coloring exists. Then by coloring with a color in , we obtain an SO -coloring of G. It is a contradiction to the fact that has no SO -coloring. ∎

In all figures, we represent a vertex that has all incident edges in the figure as a filled vertex, and a hollow vertex may not have all incident edges in the figure.

Lemma 2.3.

For an integer , let be a minimal graph with respect to such that has no SO -coloring, where . Then the following do not appear in :

-

(i)

a -vertex,

-

(ii)

a triangle such that is a -vertex and is a -vertex,

-

(iii)

two vertices with three common -neighbors,

-

(iv)

a -vertex with only -neighbors for .

Proof.

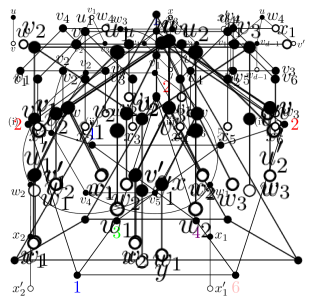

In each proof, we consider an SO -coloring of for some , and then we finish the proof by coming up with an SO -coloring of , which is a contradiction. See Figure 3.

(i) It is clear that has no isolated vertex. Suppose to the contrary that has a -vertex with neighbor . Let . Since by (2.1), we color with a color in , which gives an SO -coloring of .

(ii) Suppose to the contrary that has a triangle such that is a -vertex and is a -vertex. For an SO -coloring of , by (2.1). Since , . It is a contradiction by Lemma 2.2.

(iii) Suppose to the contrary that has two vertices and with three common -neighbors , , and . Let . Then color and with the same color of to obtain an SO -coloring of .

(iv) Suppose to the contrary that has a -vertex with only -neighbors for some . Let be -neighbors of and be the other neighbor of . For each , let be the neighbor of other than . Note that for each by (ii). Let . Note that , and for each by (2.1). We color with a color in . Let be the set of all pairs such that and . Note that by (iii), each appears at most once as an entry of an element of . Moreover, when , it holds that and by (2.1).

If and , then , , and so we can color , with distinct colors in to obtain an SO -coloring of . Suppose that or . Let for each , and . Since is a neighbor of in , . It follows that for each . If , then and so , and then we redefine and for some disjoint subsets of of size two. By applying Lemma 2.1, there is a system of odd representative for , where . Then, coloring with results in an SO -coloring of . ∎

We finish the section by stating one famous theorem in graph coloring, called Brooks’ Theorem.

Theorem 2.4 ([2]).

For a graph , . If has no component that is a complete graph or an odd cycle, then .

3 Strong odd -coloring

In this section, we prove Theorem 1.2. Let be a minimal counterexample to Theorem 1.2. In each proof in the following, we always start with defining a nonempty set , and is an SO -coloring of . We end up with an SO -coloring of .

The following is a list of reducible configurations, structures that never appear in . The configurations [C1]-[C6] are utilized in the final step to reach a contradiction.

-

[C1]

A -vertex.

-

[C2]

A -vertex for all .

-

[C3]

A -vertex for all .

-

[C4]

Two adjacent -vertices.

-

[C5]

A -vertex with two -neighbors.

-

[C6]

A -vertex with a -neighbor.

Note that [C1]-[C3] do not appear in by Lemma 2.3 (i) and (iv).

Suppose that a -vertex has a -neighbor, and is an SO -coloring of . Since , it holds that by (2.1). Thus by Lemma 2.2, the colors of the neighbors of cannot be distinct colors. We often omit this explanation when we apply Lemma 2.2.

Lemma 3.1.

The graph has no two adjacent -vertices. [C4]

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that has adjacent two -vertices and . For each , let be the -neighbor of , be the neighbor of other than and , and be the neighbor of other than . See Figure 4. Note that by Lemma 2.3 (ii). Thus , , , and are distinct, and we let . In addition, (equivalently, ) and for each by [C2]. Thus .

Lemma 3.2.

The graph has no path such that is a -vertex, is a -vertex for each , where is a common neighbor of and for some .

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that has a path path such that is a -vertex and is a -vertex for each , where is a common neighbor of and either or . Other neighbors of ’s are labeled as Figure 5. Let . By Lemma 2.3 (ii), . Note that , , , and by (2.1). Then it is possible to color with a color in for each so that the colors of ’s are distinct. It results in an SO -coloring of . ∎

Lemma 3.3.

The graph has no -vertex with two -neighbors. [C5]

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that has a -vertex with two -neighbors and . We follow the labeling of the vertices as Figure 6. Let . By Lemma 3.2, , and so has five distinct vertices. Note that for each , by Lemma 3.2. Also, , by Lemma 2.3 (ii), and by Lemma 2.3 (iv). Thus . Note that , , and for each by (2.1).

First, we color with a color in . For simplicity, let for each . Since , for each . Let . If , then we apply Lemma 2.1 to obtain a system of odd representative for , where . If , then for each by (2.1), and so we choose in for each so that . Then we color with in for each . We denote this coloring of by again. Then for each by (2.1) and so we color with a color in . Then the resulting coloring is an SO -coloring of , which contradicts to Lemma 2.2. ∎

Lemma 3.4.

The graph has no -vertex with a -neighbor. [C6]

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that has a -vertex with two -neighbors , and one -neighbor . We follow the labeling of the vertices as Figure 7. Let . Note that for each by Lemma 2.3 (ii), and so has five distinct vertices. For each , note that and by Lemma 2.3 (ii). Also, , by Lemma 2.3 (iv). Thus . Note that , for each , , and by (2.1).

First, we color with a color from . For simplicity, let for each . Since for each , for each and . Let . We color as follows.

If , then and , and so we color ’s with a same color . Suppose that it is not the case of . Without loss of generality, let . We take subsets and of and , respectively, of size exactly two. If for some , then and so we take a subset of of size two. If for each , then let . Now, we apply Lemma 2.1 to obtain a system of odd representative for . We color with for each . Then the resulting coloring is an SO -coloring of , which is a contradiction to Lemma 2.2. ∎

We complete the proof of Theorem 1.2 by discharging technique. Let be the initial charge of a vertex . Then , since . We let be the final charge of after the following discharging rules:

-

(R1)

Each -vertex sends charge to each of its -neighbors.

-

(R2)

Each -vertex without a -neighbor or -vertex sends charge to each of its -neighbors.

Take a vertex . By [C1], . If , then has only -neighbors by [C2], and so by (R1). Suppose that . If has no -neighbor, then has at most one -neighbor by [C5], so by (R2). Suppose that has a -neighbor. By [C2] and [C4], has exactly one -neighbor and two other -neighbors, which are either -vertices or -vertices having no -neighbors, and so by (R1) and (R2). Suppose that . If has at most one -neighbor, then by (R1) and (R2). If has at least two -neighbors, then has exactly two -neighbors and no -neighbor by [C2] and [C6], and so by (R1). If , then it has at most -neighbors by [C3], and so by (R1) and (R2).

From the fact that , we can conclude that every vertex has final charge exactly . Then , and if we let and be the set of -, -vertices of , respectively, and let be the set of -vertices without -neighbors. Moreover, every -vertex in has exactly one -neighbor, and so each connected component of is -regular. Lastly, note that both and are independent sets by [C2] and [C4].

Now, we finish the proof by showing that has a -coloring, which is also an SO coloring of . Let , the subgraph of induced by . Note that , since each vertex of has at most four neighbors with distance at most two in through only vertices in , and has one neighbor with distance at most two in through a vertex not in .

Lemma 3.5.

There is no connected component in that is isomorphic to .

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that there is a connected component in that is isomorphic to . Then the vertices of form a cycle in , say , and and have a common -neighbor for each . Note that ’s and ’s are distinct. See Figure 8. For each , let be a 2-neighbor of , be the neighbor of other than . If , then is a cut vertex of , which is a contradiction by permuting the colors of an SO 7-coloring of a connected component of . Thus , , and are distinct.

Let . Note that , for each , for each by (2.1). First, we color with a color in for each , with a color in for each so that the colors of seven vertices ’s and ’s are all distinct. Then we color and with the same color with . We denote this resulting coloring of as again. For each , by (2.1) and we color with a color in . It gives an SO -coloring of . ∎

4 Strong odd -coloring

Like as the previous section, in each proof, we always start with defining a nonempty set and is always an SO -coloring of .

4.1 Proof of Theorem 1.3

Let , and let be a minimal counterexample to Theorem 1.3. We will show that the following do not appear in .

-

[C1]

A -vertex.

-

[C2]

A -vertex for all .

-

[C3]

A -vertex for all .

-

[C4]

A -vertex with only -neighbors in which at least one is in .

-

[C5]

A -vertex with a -neighbor.

Note that [C1]-[C3] do not appear in by Lemma 2.3 (i) and (iv). For simplicity, let

Let . Let be a nonempty subset of . Note that . If , then by the minimality of , there is an SO -coloring of . If , then has an SO -coloring by Theorem 1.2, since . Hence, there always exists an SO -coloring of .

Lemma 4.1.

The graph has no -vertex with two -neighbors in which one is in . [C4]

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that there is a -vertex with -neighbors and . Let be the -neighbors of , be the 2-neighbor of , be the other neighbor of , and be the neighbor of other than . See Figure 9. If we have an SO -coloring of such that the colors of and are distinct, then it is a contradiction to Lemma 2.2, since always has an available color from the facts that .

Let . By Lemma 2.3 (ii), , and so has four distinct vertices. By Lemma 2.3 (iv), , , and so . Note that , , and by (2.1). If we can color with a color in for each so that their colors are distinct, then it is an SO -coloring of such that the colors of and are distinct, which contradicts to Lemma 2.2. Thus we may assume that , , and . Then , . We color and with the color and with the color . It is an SO -coloring of such that the colors of and are distinct, which contradicts to Lemma 2.2. ∎

Lemma 4.2.

The graph has no -vertex with a -neighbor or a -neighbor. [C5]

Proof.

A -vertex does not have a -neighbor by Lemma 2.3 (iv). Also, by Lemma 2.3 (iv) again. Let and be adjacent -vertices. Let for each , and be the neighbor of other than for each . See Figure 10. By Lemma 2.3 (ii), all ’s are distinct.

Claim 4.3.

For each , there is no SO -coloring of such that the color of is not equal to colors of , satisfying that if for some distinct , then .

Proof.

Suppose that there is an SO -coloring of satisfying the condition of the claim. Suppose that . Then and by assumption. Also, by (2.1), and therefore we can color with a color in for each so that the colors are distinct, which is an SO -coloring of . Suppose that , , are distinct. Let for each , and let . Note that for each . Applying Lemma 2.1, there is a system of odd representative () for . We color each with , which is an SO -coloring of . ∎

Let . Note that has eight distinct vertices. Also, and for each and by (2.1). First, suppose that are distinct for some . Let . By Claim 4.3, we cannot color with a color in for each so that the colors of are distinct. Thus we may assume that and for each , which implies that , , are distinct. Then for some and so we color , , with , and then color and with distinct colors in . It is an SO -coloring of , which contradicts to Claim 4.3.

Secondly, suppose that are not distinct for each . We may assume that and . By Lemma 2.3 (iii), and . Note that for each , for each , and for each by (2.1). If for some , say , then we color with a color in for each so that the colors of are distinct, which contradicts to Claim 4.3. Suppose that for each . Then are distinct vertices and so . Therefore, . We color with a color in . We color with a color in for each so that the colors of are distinct. We denote this coloring of by again. Then by the choice of and by (2.1). It is a contradiction to Claim 4.3. ∎

We complete the proof of Theorem 1.3 by discharging technique. Let be the initial charge of a vertex , and let be the final charge of after the discharging rules:

-

(R1)

Each -vertex in sends charge to each of its -neighbors.

-

(R2)

Each -vertex not in sends charge to each of its -neighbors.

-

(R3)

Each -vertex sends charge to each of its -neighbors.

-

(R4)

Each -vertex with at most two -neighbors sends charge to each of its -neighbors and -neighbors.

-

(R5)

Each - or -vertex without -neighbor sends charge to each of its -neighbors and -neighbors.

Take a vertex . We will show that . By [C1], . Suppose that . Then has only -neighbors by [C2]. If has no neighbor in , then by (R2) and (R3). If has a neighbor in , then by [C4] also has a -neighbor and so by (R1) and (R3).

Suppose . By [C2], it has at most one -neighbor. If has no -neighbor, then by (R5). Suppose is a -vertex. If , then by (R1), . Suppose that . Then has at least one -neighbor that is not a -vertex. Then is either a -vertex without -neighbors, a -vertex with at most two 2-neighbors by [C5], or a -vertex. By (R4) and (R5), .

Suppose that . Then it has at most three -neighbors by [C3]. If has at most two -neighbors, then by (R3) and (R4), . Suppose that has three -neighbors. Let be the -neighbor of . Then is neither a -vertex nor a -vertex by [C5] and so sends to by (R4) and (R5). Then . If , then it has at most -neighbors and so by (R3) and (R5). Thus for each vertex . Since , we have for each vertex . Thus is either -, -, or -vertex. Since , there is a -vertex in . By [C3], there is a -neighbor of . However, is neither a -vertex nor a -vertex by [C5], which is a contradiction.

4.2 Proof of Theorem 1.4

Let be a minimal counterexample to Theorem 1.4. We will show that the following do not appear in .

-

[C1]

A -vertex.

-

[C2]

A -vertex for all .

-

[C3]

A -vertex with two -neighbors.

Note that [C1] and [C2] do not appear in by Lemma 2.3 (i) and (iv).

Lemma 4.4.

The graph has no triangle consisting of -vertices.

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that has a triangle consisting of only -vertices. Let be the -neighbor of and for each . See Figure 11. Let . By Lemma 2.3 (ii), , , are distinct, and so has distinct six vertices. Note that ’s are distinct by Lemma 2.3 (iv).

By (2.1), , and for each . If we can choose a color in for each to color with distinct colors, then it results in an SO -coloring of . Thus and so . Since and , it follows that for some . We color and with . For , we color with a color in so that all colors of the vertices in are distinct. It is an SO -coloring of . ∎

Lemma 4.5.

The graph has no -vertex with two -neighbors.[C3]

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that has a vertex . We follow the labeling of the vertices as Figure 12. Note that , , , , and are distinct since has no -cycle. Let . By Lemma 2.3 (ii), for each , and so has six distinct vertices. Note that for each , , by Lemma 2.3 (ii). Also, , , by Lemma 2.3 (iv), and by Lemma 4.4. Thus .

In addition, , , are distinct by Lemma 2.3 (iv). Note that for each by (2.1). Also, since is a -vertex in , by (2.1).

Claim 4.6.

.

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that . We give a color to , , and , and denote this coloring of by again. Note that for each by (2.1). Next, we color with a color in for each .

If there is a color in , then we color with the color and it is done. Thus . Moreover, and so for each . Coloring both and with gives an SO -coloring of . ∎

Claim 4.7.

There is a color for each such that .

Proof.

Recall that and . Suppose that for each . Then . An element in belongs to , a contradiction to Claim 4.6. Thus for some . We may assume that . We take and , and so . ∎

We color with for each , where and satisfy Claim 4.7, and denote this coloring of by again. Then for each , by (2.1), and

Claim 4.8.

There is no SO -coloring of that is an extension of such that the color of is not .

Proof.

Suppose that we color , , and to obtain an SO -coloring of satisfying . By the choice of and , there is at least one available color in . It contradicts to Lemma 2.2. ∎

Let . Note that . If there is a color for some , then coloring , and with , and , respectively, gives an SO -coloring of such that , which contradicts to Claim 4.8. Thus , and so

| (4.1) |

Note that for every , by the definition of for each and for some .

Claim 4.9.

For every , it holds that and .

Proof.

By (4.1), for every . Suppose to the contrary for some . Without loss of generality, let . If , then we color , , and with a color in , , and , respectively, which gives an SO -coloring of such that the color of is not , a contradiction to Claim 4.8. Thus and so by (), . Then we color , , and with , , and , respectively, which gives an SO -coloring of . Then the color of is not and so it is a contradiction to Claim 4.8. Thus and so for every . Therefore each is a subset of . ∎

If , then for each , by Claim 4.9 and so by (). Then we color , , and with , and it is an SO -coloring of such that the color of is not , which contradicts to Claim 4.8. Thus .

In addition, by Claim 4.9, since ,

Claim 4.10.

For some , and .

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that each satisfies (P) or (Q), where (P) and (Q) are properties defined as follows: (P) and (Q) .

By (), does not satisfy (Q) for some . Then satisfies (P), and so by (). Then does not satisfy (Q). By the assumption, also satisfy (P) and so by (). Since by Claim 4.9, there is . By the definition of , , and so for each . It is a contradiction to (). ∎

We complete the proof of Theorem 1.4 by discharging technique. Let be the initial charge of a vertex , and be the final charge of after the following discharging rules:

-

(R1)

Each -vertex sends charge to each of its -neighbors.

-

(R2)

Each -vertex without -neighbors sends charge to each of its -neighbors.

Take a vertex . We will show that . By [C1], . If , then has only -neighbors by [C2], and so by (R1). Suppose . By [C2], it has at most one -neighbor. If has no -neighbor, then by (R2). Suppose is a -vertex. By [C3], it has at most one -neighbor, and so has at least one -neighbor without 2-vetices. By (R1) and (R2), . Thus for each vertex . Since , we have for each vertex .

Let be the set of -vertices, be the the set of -vertices, and be the the set of -vertices not in . The final charge of each vertex is exactly , and it implies that forms an induced matching, and forms an independent set. We color each -vertex with a color 1, each -vertex in with a color . We will color the vertices of with colors as follows. Let , subgraph of induced by . Then . Moreover, by the structure of , cannot have as a connected component. By Theorem 2.4, there is a proper coloring of with the color set , and we color each vertex with the color . Then one can check that it is an SO coloring of , a contradiction.

5 Remarks

Acknowledgements

This work was supported under the framework of international cooperation program managed by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2023K2A9A2A06059347).

References

- [1] O. V. Borodin and A. O. Ivanova. List 2-facial 5-colorability of plane graphs with girth at least 12. Discrete Math., 312(2):306–314, 2012.

- [2] R. L. Brooks. On colouring the nodes of a network. Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc., 37:194–197, 1941.

- [3] Y. Bu and C. Shang. List 2-distance coloring of planar graphs without short cycles. Discrete Math. Algorithms Appl., 8(01):1650013, 2016.

- [4] Y. Bu and J. Zhu. Channel Assignment with r-Dynamic Coloring: 12th International Conference, AAIM 2018, Dallas, TX, USA, December 3–4, 2018. In Proceedings, pages 36–48, 2018.

- [5] Y. Bu and X. Zhu. An optimal square coloring of planar graphs. J. Comb. Optim., 24(4):580–592, 2012.

- [6] Y. Caro, M. Petruševski, and R. Škrekovski. Remarks on odd colorings of graphs. Discrete Appl. Math., 321:392–401, 2022.

- [7] E.-K. Cho, I. Choi, H. Kwon, and B. Park. Odd coloring of sparse graphs and planar graphs. Discrete Math., 346(5):113305, 2023.

- [8] D. W. Cranston. Coloring, list coloring, and painting squares of graphs (and other related problems). arXiv preprint, page arXiv:2210.05915, 2022.

- [9] D. W. Cranston. Odd colorings of sparse graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.01455, 2022.

- [10] D. W. Cranston, M. Lafferty, and Z.-X. Song. A note on odd colorings of 1-planar graphs. Discrete Appl. Math., 330:112–117, 2023.

- [11] T. Dai, Q. Ouyang, and F. Pirot. New bounds for odd colourings of graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.01341, 2023.

- [12] Z. Deniz. An improved bound for 2-distance coloring of planar graphs with girth six. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.03831, 2022.

- [13] Z. Deniz. On 2-distance ()-coloring of planar graphs with girth at least five. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.02201, 2023.

- [14] W. Dong and B. Xu. 2-distance coloring of planar graphs with girth 5. J. Comb. Optim., 34:1302–1322, 2017.

- [15] V. Dujmović, P. Morin, and S. Odak. Odd colourings of graph products. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.12882, 2022.

- [16] Z. Dvořák, R. Škrekovski, and M. Tancer. List-coloring squares of sparse subcubic graphs. SIAM J. Discrete Math., 22(1):139–159, 2008.

- [17] S. G. Hartke, S. Jahanbekam, and B. Thomas. The chromatic number of the square of subcubic planar graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1604.06504, 2016.

- [18] H. La. 2-distance list (+ 3)-coloring of sparse graphs. Graphs Comb., 38(6):167, 2022.

- [19] R. Liu, W. Wang, and G. Yu. 1-planar graphs are odd 13-colorable. Discrete Math., 346(8):113423, 2023.

- [20] J. Petr and J. Portier. The odd chromatic number of a planar graph is at most 8. Graphs Comb., 39(2):28, 2023.

- [21] M. Petruševski and R. Škrekovski. Colorings with neighborhood parity condition. Discrete Appl. Math., 321:385–391, 2022.

- [22] C. Thomassen. The square of a planar cubic graph is 7-colorable. J. Comb. Theory, Ser. B, 128:192–218, 2018.

- [23] T. Wang and X. Yang. On odd colorings of sparse graphs. Discrete Appl. Math., 345:156–169, 2024.

- [24] G. Wegner. Graphs with given diameter and a coloring problem. Technical report, University of Dortmund, 1977.