Spatially-resolved spectro-photometric SED Modeling of NGC 253’s Central Molecular Zone

Abstract

Context. Studying the interstellar medium in nearby starbursts is essential for gaining insights into the physical mechanisms driving these extreme objects, thought to be analogs of young, primeval, star-forming galaxies. This task is now feasible due to deep spectro-photometric data enabled by rapid advancements in ground- and space-based facilities. To fully leverage this wealth of information, extracting insights from the spectral line properties, and the spectral energy distribution (SED) is imperative.

Aims. This study aims to produce and analyze the physical properties of the first spatially-resolved multi-wavelength SED of an extragalactic source that covers six decades in frequency (from near-ultraviolet to centimeter wavelengths) at an angular resolution of 3′′ which corresponds to linear scale of 51 pc at the distance of NGC 253. We focus on the central molecular zone (CMZ) of this starburst galaxy, which contains giant molecular clouds (GMCs) responsible for half of the galaxy’s star formation.

Methods. We retrieve archival data from optical to centimeter wavelengths, covering six decades of spectral range. We compute SEDs to fit the observations using the GalaPy code and confronting results with the CIGALE code for validation. We also employ starlight library to analyze the stellar optical spectra of the GMCs.

Results. Our results reveal significant differences between central and external GMCs in terms of stellar and dust masses, star formation rates (SFRs), and bolometric luminosities, to provide a few. We have obtained tight relations between monochromatic stellar tracers and star-forming conditions obtained from panchromatic emission. We find that the best SFR tracers are radio continuum bands at 33 GHz, radio recombination lines (RRLs), and the total infrared (IR) luminosity range (LIR; 8–1000m) as well as the IR emission at 60m. The emission line diagnostics based on the BPT and WHAN diagrams suggest that the nuclear region of NGC 253 exhibits shock signatures, placing it in the composite zone typically associated with AGN/star-forming region hybrids, while the AGN fraction from panchromatic emission is negligible (7.5%).

Conclusions. Our findings demonstrate, using an extensive dataset and through robust methods, the significant heterogeneity within the CMZ of NGC 253, with central GMCs exhibiting high densities, elevated SFRs, and greater dust masses compared to their external counterparts. We confirm the effectiveness of certain centimeter photometric bands as a reliable method to estimate the global SFR, in accordance with previous studies but this time at GMC scales.

Key Words.:

galaxies: starburst – galaxies: individual: NGC 253 – galaxies: star formation – galaxies: ISM1 Introduction

The panchromatic spectral energy distribution (SED) of an astrophysical system encapsulates the intricate interplay among its various components, including stars in different evolutionary phases and their remnants; molecular, atomic, and ionized gas; dust, and compact objects such as supermassive black holes. It contains the imprints of baryonic processes that drive its formation and evolution across the cosmic times. Comparison of SEDs at different emission wavebands provides key insights into the origin and nature of emission and the factors that set their energy balance. Therefore, modeling a SED is one of the most effective tools, if not the most effective, for estimating the specific star formation rate (sSFR), from which the star formation rate (SFR) and the stellar mass () can be derived. This method relies on reconstructing the stellar emission through star formation history (SFH) models, which can be either purely theoretical or non-parametric (the latter refers to models that do not assume a specific functional form and rely on templates to infer the SFH; see, e.g., Cid Fernandes et al. 2005; da Cunha et al. 2008; Conroy 2013a). SED fitting allows for a detailed analysis of the light emitted across different wavelengths, providing insights into the age, metallicity, and dust content of the stellar population (e.g., Bruzual & Charlot, 2003).

While SEDs have been extensively applied to high-redshift galaxies, there are inherent resolution limitations, particularly at far-infrared (FIR) wavelengths. For example, the Herschel SPIRE beam has a resolution of 36 at 500 m, corresponding to roughly 1 kpc at , meaning that the observed SEDs often conflate contributions from recent star formation, AGN, and/or stellar outflows, and sub-thermally excited gas, to mention a few. Considering also that a photometric aperture of 2.5 times the beam, assuming a Gaussian profile for the emission source, ensures the capture of extended emission, the problem becomes more critical. Given these constraints, to gain a deeper understanding of the relevant processes affecting galaxies, such as epochs with galaxy-galaxy interactions or times when their star formation began to decline (e.g., Hopkins & Beacom, 2006; Hopkins et al., 2010), it is imperative to focus on local analogs. In this regard, the extensively studied nearby starburst galaxy NGC 253 serves as an ideal target due to its proximity and intense nuclear star formation, which mirrors conditions seen in distant galaxies (Leroy et al., 2015). Focusing on spatially-resolved objects, such as giant molecular clouds (GMCs), allows us to take a significant step forward in producing SED fittings with unprecedented detail, overcoming the aforementioned limitations.

NGC 253 is a nearby starburst galaxy about 3.5 Mpc away with a steep inclination ranging from approximately 70∘ to 79∘ (Rekola et al., 2005; Pence, 1980; Iodice et al., 2014). Its inner kiloparsec (kpc) region is a hub of vigorous star formation, generating a rate of roughly 1.7 solar masses per year, which constitutes about half of the galaxy’s total star formation activity (Bendo et al., 2015; Leroy et al., 2015). This active star-forming core encompasses a central molecular zone (CMZ), spanning around 300 parsecs in length and 100 parsec in width projection (Sakamoto et al., 2011) and hosting ten giant molecular clouds (GMCs) discerned through molecular and continuum emissions at high resolution (Leroy et al., 2015). Notably, studies indicate that an active galactic nucleus (AGN) has minimal impact on the molecular gas within NGC 253’s CMZ (Fernández-Ontiveros et al., 2009; Müller-Sánchez et al., 2010; Pérez-Beaupuits et al., 2018), making it an excellent test-bed to study pure star-forming conditions.

The CMZ of NGC 253, along with its GMCs, has been the focus of the ALMA Comprehensive High-resolution Extragalactic Molecular Inventory (ALCHEMI) program (Martín et al., 2021). This project delves into chemical changes caused by shocks or cosmic ray flux density variations, some of them also aiming for a direct comparison with galaxy conditions, the discovery of new molecules, and the characterization of the GMCs that highlights differences between the very central part of the CMZ and its outskirts (Holdship et al., 2021; Harada et al., 2021; Martín et al., 2021; Behrens et al., 2022; Holdship et al., 2022; Humire et al., 2022; Harada et al., 2022; Butterworth et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2023; Behrens et al., 2024; Bouvier et al., 2024; Tanaka et al., 2024; Harada et al., 2024).

Previous studies of the NGC 253 spectral energy distribution (SED) have focused on specific wavelength regimes like optical/IR (Fernández-Ontiveros et al., 2009), mid-IR to (sub-)millimeter (Pérez-Beaupuits et al., 2018), far-UV to far-IR (Beck et al., 2022), the Rayleigh-Jeans tail (Martín et al., 2021), radio (1 GHz) to sub-mm (350 GHz) (Belfiori et al., submitted) and low-frequency radio (MHz to 11 GHz) regimes (Kapińska et al., 2017). However, there remains significant potential in extending these investigations across a broader wavelength regime. This extension can provide valuable insights into various physical processes, including opacity levels, the (s)SFR, and the mass-to-dust rates, to provide a few.

In the present article, we aim to create the first extragalactic panchromatic SED (near-ultraviolet to centimeter wavelengths) performed at a linear resolution of 51 pc or 3″, at the order of magnitude of a giant molecular cloud. For the specific case of this article, given the massive amount of information extracted, we will focus on the stellar processes derived per GMC, such as the SFRs and SFHs.

Along with the acquisition of our new results, we also highlight the importance of testing tracers or proxies that focus on a single wavelength range against the values provided by the full SED to understand the scope of the former in terms of luminosity, ages, object classifications, and calculated SFRs. This way, one can gauge their effectiveness on a larger spectro-photometric wavelength scale.

In the following sections, we will present the collected observations (Sect. 2), our SED and spectroscopic modeling (Sect. 3), our results with small discussions inside (Sect. 4), and a general discussion on common limitations of our methods and the placement of our findings in a high-z perspective (Sect. 5), before providing our conclusions in Sect. 6.

2 Observations

To ensure consistency in the physical scales analyzed, we extract fluxes using a uniform aperture size with a 3 diameter, despite the varying angular resolutions across the sample. The coordinates of all GMCs are listed in Table 1. A summary of the dataset used in this study is provided in Table 5. An over-view of the full information used in this work is presented in Fig. 1. Below, we provide a detailed description of the observations conducted with each facility.

2.1 S-PLUS

The Southern Photometric Local Universe Survey (S-PLUS; Mendes de Oliveira et al. 2019) will cover 9,300 deg2 of the southern hemisphere (currently 80% complete), employing 7 narrow-band and 5 broad-band filters, encompassing a wavelength range from 3,533 Å ( filter) to 8,941 Å ( filter). The angular resolution is subject to weather conditions, with a typical seeing range of 08 to 20 and an average of 15.

For this work, we have used images in all 12 available filters from the S-PLUS fifth data release (available for the internal collaboration), maintaining a consistent angular resolution of 15 (25.4 pc). For further details on the S-PLUS survey, we refer the reader to Mendes de Oliveira et al. (2019) and Herpich et al. (2024).

| Position | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| [00h:47m:–s] | [-25∘:17’:–”] | [km s-1] | |

| GMC 1 | 31.93 | 29.00 | 304 |

| GMC 2 | 32.36 | 18.80 | 330 |

| GMC 3 | 32.81 | 21.55 | 286 |

| GMC 4 | 32.97 | 19.97 | 252 |

| GMC 5 | 33.16 | 17.30 | 231 |

| GMC 6 | 33.33 | 15.70 | 180 |

| GMC 7 | 33.65 | 13.10 | 174 |

| GMC 8 | 33.94 | 10.90 | 205 |

| GMC 9 | 34.14 | 12.00 | 201 |

| GMC 10 | 34.24 | 7.84 | 144 |

2.2 VLT & HST

The study incorporated Adaptive Optics images obtained from both the Very Large Telescope/NaCo (VLT/NaCo) and VISIR (VLT/VISIR), in addition to Hubble Space Telescope (HST) images sourced from Fernández-Ontiveros et al. (2009), and we refer the reader to that work for further details.

The VLT/NaCo observations were conducted on December 2 and 4, 2005, utilizing the IR wavefront sensor (dichroic N90C10) for atmospheric correction. The observation included the following filters and integration times: J (600 s; 3% Strehl ratio222which is a measure of the quality of adaptive optics correction, indicating the ratio of the peak intensity of the observed point spread function to the ideal diffraction-limited one (SR)), Ks (500 s; 20% SR), L (4.375 s; 40% SR), and NB4.05 (8.75 s, centered on Br; 40% SR). The resulting images achieved different Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) resolutions: 029 (J), 024 (Ks), 013 (L), and 014 (NB4.05). Images from VLT/VISIR, captured on December 1, 2004, and October 9, 2005, encompassed the N (PAH22, 11.88m, 0.37m; 2826 s) and Q (Q2, 18.72m, 0.88m; 6237 s) bands. The achieved FWHM resolutions were 04 (N) and 074 (Q). Furthermore, HST images were utilized within the central 300 pc region of NGC 253, employing the F555W (V band), F656N (H), F675W (R band), F814W (I band), and F850LP filters.

| Source | [Å] | FWHM [] | [] | GMC 1 | GMC 2 | GMC 3 | GMC 4 | GMC 5 | GMC 6 | GMC 7 | GMC 8 | GMC 9 | GMC 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPLUS/uJAVA | 3563 | – | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.04 | |

| SPLUS/J0378 | 3770 | – | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.06 | |

| SPLUS/J0395 | 3940 | – | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.08 | |

| SPLUS/J0410 | 4094 | – | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.13 | |

| SPLUS/J0430 | 4292 | – | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.18 | |

| SPLUS/gSDSS | 4751 | – | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.31 | |

| SPLUS/J0515 | 5133 | – | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.37 | |

| HST/F555W | 5443 | – | – | – | – | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.89 | 0.79 | – | – | |

| SPLUS/rSDSS | 6258 | – | 0.35 | 0.42 | 1.07 | 1.56 | 1.22 | 1.24 | 1.43 | 1.37 | 1.10 | 0.87 | |

| SPLUS/J0660 | 6614 | – | 0.43 | 0.56 | 1.89 | 3.27 | 2.39 | 2.16 | 2.35 | 1.94 | 1.49 | 1.13 | |

| HST/F675W | 6718 | – | – | – | – | 2.46 | 1.96 | 1.86 | 2.05 | 1.69 | – | – | |

| SPLUS/iSDSS | 7690 | – | 0.65 | 0.84 | 2.56 | 3.94 | 3.08 | 2.90 | 2.80 | 2.53 | 1.91 | 1.53 | |

| HST/F814W | 7996 | – | – | – | – | 6.28 | 4.81 | 4.15 | 3.78 | 2.98 | – | – | |

| SPLUS/J0861 | 8611 | – | 0.88 | 1.24 | 3.94 | 6.46 | 5.20 | 4.71 | 4.08 | 3.40 | 2.55 | 2.01 | |

| SPLUS/zSDSS | 8831 | – | 1.07 | 1.52 | 5.11 | 9.07 | 7.08 | 6.07 | 4.97 | 4.06 | 2.93 | 2.35 | |

| HST/F850LP | 9114 | – | – | – | – | 12.53 | 8.93 | 6.95 | 5.48 | 3.87 | – | – | |

| VLT/J | 12650 | – | – | – | 22.01 | 45.75 | 31.77 | 20.08 | 9.88 | – | – | – | |

| VLT/K | 21800 | – | – | – | 31.16 | 93.29 | 71.15 | 39.01 | – | – | – | – | |

| Spitzer/IRAC 3.6m | 36000 | – | 2.71 | 5.72 | 28.40 | 106.38 | 109.02 | 62.01 | 23.41 | 12.60 | 6.27 | 6.30 | |

| Spitzer/IRAC 4.5m | 45000 | – | 2.43 | 4.78 | 28.08 | 150.28 | 150.45 | 69.47 | 21.64 | 10.77 | 5.20 | 5.79 | |

| Spitzer/IRAC 5.8m | 58000 | – | 7.23 | 17.75 | 121.03 | 357.56 | 464.85 | 250.73 | 89.61 | 45.28 | 22.27 | 22.98 | |

| Spitzer/IRAC 8.0m | 80000 | – | 18.98 | 52.71 | 335.32 | 1016.10 | 1095.98 | 644.08 | 243.56 | 120.51 | 60.60 | 61.62 | |

| VLT/N | 118800 | – | – | – | 287.88 | 3207.94 | 1273.06 | 477.52 | 121.49 | – | – | – | |

| VLT/Q | 187200 | – | – | – | 1178.25 | 18901.04 | 9984.58 | 3340.52 | 654.91 | 355.37 | – | – | |

| ALMA/B7 | 9252854 | 15 | 11.48 | 9.63 | 188.92 | 289.28 | 343.56 | 255.51 | 51.86 | 18.37 | 18.35 | 17.51 | |

| ALMA/B6 | 12337138 | 15 | 2.58 | 3.28 | 68.74 | 122.77 | 165.38 | 103.49 | 17.11 | 5.82 | 5.17 | 6.45 | |

| ALMA/B5 | 16031682 | 15 | 2.85 | 1.91 | 35.92 | 72.02 | 110.39 | 58.05 | 8.34 | 3.07 | 2.86 | 2.64 | |

| ALMA/B4 | 20818921 | 15 | 1.29 | 1.57 | 24.13 | 56.96 | 101.44 | 40.57 | 5.76 | 2.37 | 1.69 | 2.50 | |

| ALMA/B3 | 29979246 | 15 | – | – | 18.41 | 50.46 | 102.15 | 33.61 | 3.60 | – | – | 1.27 | |

| EVLA Band Ka (DnC) | 91330642 | 1.761.39 | 44 | – | – | 21.80 | 59.07 | 141.84 | 40.53 | 4.91 | – | – | 1.54 |

| VLA Band K (B) | 127245834 | 0.470.26 | 7.9 | – | – | – | – | 135.60 | – | – | – | – | – |

| VLA Band Ku (B) | 200665639 | 0.670.40 | 12 | – | – | 30.67 | 71.92 | 181.58 | 50.21 | – | – | – | – |

| EVLA Band X (A) | 299773911 | 0.460.19 | 5.3 | – | – | – | 98.03 | 264.56 | 81.33 | – | – | – | – |

| VLA Band C (A) | 616844217 | 0.690.39 | 8.9 | – | – | 41.34 | 104.45 | 318.02 | 70.16 | 9.08 | – | – | – |

| VLA Band L (A) | 2012164964 | 2.131.25 | 36 | 6.57 | 12.38 | 89.09 | 175.32 | 274.92 | 160.83 | 36.35 | 16.68 | 15.20 | 5.69 |

2.3 Spitzer/IRAC

We retrieved Spitzer/IRAC mosaic images from the Spitzer Heritage Archive666https://irsa.ipac.caltech.edu/data/SPITZER/Enhanced/SEIP/. The mean FWHM of the point spread function (PSF) of the four IRAC bands at 3.6, 4.5, 5.8, and 8.0 are 166, 172, 188, and 198, respectively (Fazio et al., 2004, their Table 3). Thanks to the large field of view (FoV) of Spitzer, which covers the entire emission from NGC 253, we were able to use data from these four IRAC filter images in all our GMCs.

2.4 ALMA

ALMA observations of NGC 253 were conducted during Cycles 5 and 6 as part of the ALCHEMI large program. The observations consisted on an unbiased complete spectral scan across the ALMA bands 3 to 7 (84–373 GHz, =3.6–0.8 mm) across the whole CMZ region (inner 500 pc; Sakamoto et al. 2006) of the galaxy. The observations were carried out using both 12m and 7m antenna arrays aiming to retrieve extended emission, and the data were imaged to common angular and spectral resolutions of 16 and 8–9 km s-1, respectively. The flux density RMS noise ranges from 0.18 to 5.0 mJy beam-1 in the 8–9 km s-1 channels. In Fig. 2 we provide integrated intensity maps of the continuum emission (in mJy) of the CMZ of NGC 253 at ALMA Bands 3, 4, 6, and 7 (100, 144, 243, and 324 GHz, respectively).

The absolute flux density uncertainty was reported to be of 10 to 15%. We conservatively assume an uncertainty of 15% for our extracted ALCHEMI fluxes. However, the relative flux uncertainty within the individual ALCHEMI observations is after the alignment performed on the data enabled by the continuous frequency coverage. A full description of the dataset, calibration, and imaging is provided by Martín et al. (2021).

2.5 EVLA

We obtained Expanded Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (EVLA) archival data in two different ways. One was by directly searching into the VLA archive. In this way, we obtained the reduced NGC 253’s CMZ image in the X Band at 3 cm (PI: N. Harada), which has been observed in A configuration mode, leading to a maximum recoverable scale (MRS) of 53 according to the EVLA documentation777https://science.nrao.edu/facilities/vla/docs/manuals/oss2012B/performance. We applied a cleaning to this data using tclean with a standard gridder and a hogbom deconvolver inside the Common Astronomy Software Applications (CASA) package888https://casa.nrao.edu/index.shtml. Additionally, we used 1 cm (33 GHz; Ka-Band) continuum image presented in Kepley et al. (2011). These observations were done at DnC hybrid configuration, which leads to an MRS of 44999according to the smaller array extension of the hybrid configuration, configuration C for this case. We used CASA imsmooth to convolve the X Band EVLA continuum image to a common circular beam of 16, matching that of ALCHEMI. In the same way, for the Ka-Band (26.5–40.0 GHz) image, we choose a slightly larger (18) beam due to an original beam of 176138. Since the images are in Jy/beam, we converted them into Janskys by dividing their flux by the beam area in pixels [pix/beam] available in the CASA Viewer (Statistics/BeamArea) panel. We note that the largest angular scale, (see Table 5), is smaller than the aperture size for the Ka-Band observations. However, we did not see significant deviations of these observations with respect to the rest of the dataset. In fact, the model adjusts well to the observations when they are available (GMCs 3–7), and any expected departure or uncertainty in flux is compensated for by the added uncertainties in our SED models, which is up to 30% for the case of GalaPy (Ronconi et al., 2024).

2.6 VLA

We retrieve Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) continuum maps processed with the AIPS VLA pipeline by Lorant Sjouwerman (NRAO) from the webpage: https://www.vla.nrao.edu/astro/nvas/. Of those, VLA Band L (VLA A conf.) is the only one were all the 10 GMCs studied in this work are detectable. Details about wavelengths, fluxes per GMC, array configurations, and FWHMs, are summarized in Table 2. We find very good consistency between VLA and EVLA points, delivering similar fluxes within 1 or 2 of the SED fitting. There is a noticeable missing flux in L-band for GMC 5 (see Fig. 3), which can be associated to the free-free absorption effect (e.g., Kellermann & Pauliny-Toth, 1969) observed in compact IR-bright starbursts (Condon et al., 1991; Clemens et al., 2010; Dey et al., 2022).

Since we are considering flux densities, we decided not to deconvolve our VLA continuum maps, as we noticed that it can produce artifacts that may show up in GMC positions without clear emission, leading to false positives. Upon examining the summed fluxes within 3 diameter apertures before and after deconvolution with CASA imsmooth, we observed differences of less than 10% (i.e., less than instrumental uncertainties).

2.7 GMC Positions

The selection of GMC positions to be analyzed in this study is driven by the ALMA data from the ALCHEMI project. Thus, we use the GMC positions determined by Harada et al. (2024), which incorporate both the continuum and molecular emission peaks, except for GMC 3, GMC 4, and GMC 10. For these three clouds, and given the similarity between the dataset used in Leroy et al. (2015) and the ALCHEMI data, A. K. Leroy (private communication) provided modified GMC coordinates tailored to the ALCHEMI data for the collaboration, which were retained for GMCs 3, 4, and 10. These three GMC positions were derived using CPROPS (Rosolowsky & Leroy, 2006) considering intensity peaks of the CS and H13CN transitions. Our region coordinates are very close to those used by Leroy et al. (2015).

The general reason for this selection is to avoid, as much as possible, overlapping between our apertures of 3, while at the same time extracting most of the intensity in each aperture. We note that the variation in the GMC positions from different source extraction criteria is relatively marginal (02) compared to the apertures used in this paper.

Along the course of this work, we will compare our GMC characteristics with those of the GMCs in previous ALCHEMI works with the same numbering, unless it is explicitly mentioned.

3 Analysis: SED and Spectroscopic modeling

The main results from this study come from two methods used to explore in detail the spectroscopic and photometric information of the CMZ of NGC 253. We have employed GalaPy for the photometry information, from near-UV to centimeter wavelengths. To cross-validate the results obtained from GalAPy, we compared them with those from CIGALE. CIGALE is a robust SED modeling, continuously improved over the years by both its original developers and the broader astronomical community.

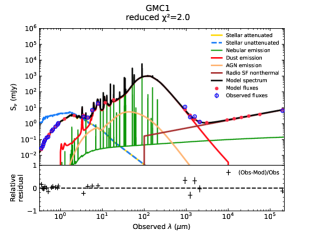

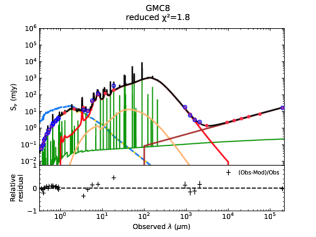

Additionally, to complement this study, we applied starlight for the spectral MUSE data plus photometric (S-PLUS) information in the near-UV to near-IR range. Below, we elaborate on our procedures. In Fig. 3 we provide our best-fit models to the extracted flux densities summarized in Table 5. This Figure primarily shows GalaPy results but also presents the CIGALE best-fit models (solid magenta lines). CIGALE best-fitting results are further provided in detail (i.e., with all the considered components) in Fig. 14.

3.1 GalaPy photometric SED fitting

We perform the SED fitting of our selected GMCs with GalaPy (Ronconi et al., 2024), an open-source application programming interface developed in Python/C tailored for this task across a range from X-ray to radio frequencies. GalaPy assumes a Chabrier initial mass function (IMF; Chabrier, 2003) and a flat CDM cosmology with approximate parameters: matter density around 0.3, baryonic density around 0.05, and a Hubble constant 100 km s-1 Mpc-1, where is roughly 0.7 (Planck Collaboration et al., 2020). GalaPy is expected to include tools for optical spectroscopy and AGN component on top of its SED fitting algorithm. In the subsequent subsections, we detail the relevant configurations pertinent to the objectives of this study.

3.1.1 The In-Situ model

GalaPy allows the user to choose among a range of SFH models, both empirical and non-parametric. For our models, we use the default In-Situ SFH model, which has proven successful in predicting the emission from both late and early type galaxies in the local Universe as well as for young highly star-forming systems up to high redshift (Ronconi et al., 2024). The physically motivated In-Situ model, developed by Lapi et al. (2018), adopts a star formation rate () of:

| (1) |

with , where is the galactic age, is the characteristic star-formation timescale, is related to the gas condensation, and is related to the gas dilution, recycling, and stellar feedback (see Lapi et al., 2020, for more details).

In the in situ model, the evolution of the gas and dust masses and of the gas and stellar metallicities can be followed analytically as a function of the galactic age, and self-consistently with respect to the evolution of the SFR. This means that an isolated system is assumed for each molecular cloud (MC), implying an interdependence among parameters. For example, a correspondence between metallicities and ages. This approach guarantees that the derived physical properties that directly result from the evolution of the stellar population (e.g. the components’ masses and metallicities), are consistently propagated to the other models contributing to the overall emission of the object.

3.1.2 Simple Stellar Populations

Among the available Simple Stellar Population (SSP) libraries in GalaPy, we have selected the “refined” version of (Bressan et al., 2012; Yan et al., 2019; Ronconi et al., 2024) as our preferred choice. This library ensures a dense wavelength grid with a minimum of 128 values per order of magnitude within its 2189-point grid. It incorporates emission from dusty Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB) stars and accounts for nebular emission and free-free continuum in addition to the stellar continuum and non-thermal synchrotron radiation from core-collapse supernovae.

For the purposes of our study, the SSP library was modified to correctly process the photometric points obtained from the narrow bands of the VLT/VISIR instrument (see Sect. 2.2). This adjustment will be available in the next release of GalaPy.

3.1.3 Dust model

GalaPy implements an age-dependent two component dust model which is constructed in order not to assume an attenuation curve but to derive it instead from structural parameters (e.g. density and extension) which can be obtained by tuning the model to best represent an observed dataset.

The two different components comprise the contribution of (1) a hot molecular cloud phase (normally referred in the literature as a “birth-molecular cloud”; see, e.g., Charlot & Fall 2000) of new stellar populations and (2) a diffuse and extended dusty medium which further attenuates the stellar emission. Both components also contribute to the IR emission which is then the combination of two separate modified grey-bodies.

Among the several possible free parameters on which this dust model depends, we chose to fix some known values and ranges, in order to both ensure physically plausible results and speed up the computing process. This consists in setting a range of reliable physical terms, such as the total number of molecular clouds to , as in this work we are assuming isolated GMCs, and their dusty and molecular radii, which were set to be within a 10–100 pc range, although they will likely be closer to the lower limit considering the 30 pc diameter inferred from their sub-mm emission (Leroy et al., 2015). A list of all common parameter ranges and individual values used to model the SEDs in the ten GMCs is provided in Table 3. There, the redshift was taken from the SIMBAD Astronomical Database (Wenger et al., 2000). These ranges are fixed for all GMCs. On the other hand, the parameters that were fine-tuned for specific GMCs along with their corresponding adjusted ranges are presented in Table 4. The parameters listed in this second table vary across different GMCs, with their respective ranges for each GMC. For example, the range of the molecular cloud radius, RCM, was fine-tuned and is set between 0.0 and 1.7 for GMCs 2 and 8, while for GMCs 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10, it remains between 0.0 and 2.0 (in log10 scale).

We use different initial conditions for unknown parameter ranges such as the GMC ages (age), the time of maximum star-formation (sfh.tau_star), the time that stars need to escape from its parental molecular cloud (ism.tau_esc), the maximum SFR (sfh.psi_max), and the average radius of the molecular cloud (ism.R_MC). We mainly modified the R_MC, ism.R_MC, and sfh.psi_max in cases where the results were bimodal, in order to achieve a single result in the parameter space distribution. For example, the R_MC was fixed to not exceed 50 pc in GMCs 2 and 8, motivated by Table 3 in Leroy et al. (2015), where their molecular radii are expected to be around 52 and 44 pc, respectively. Interestingly, these two GMCs are the largest in the sample, according to the mentioned study.

We recommend the reader to see Table B.3 in Ronconi et al. (2024), also described in its web-page101010https://galapy.readthedocs.io/en/latest/general/free_parameters.html, to find a complete description of all GalaPy parameters, beyond the ones described in the present work, which assumes and is restricted to the In-Situ model.

| Parameter | Value/Range | Brief description |

|---|---|---|

| redshift | 0.000864 | |

| sfh.tau_quench | 1e+20 | Star formation quenching (yrs.) |

| ism.f_MC | ([0.0, 1.0], lin) | MCs’ fraction into the ISM |

| ism.norm_MC | 100.0 | MCs’ normalization factor |

| ism.N_MC | 1.0 | number of MCs |

| ism.dMClow | 1.3 | Extinction index 100 |

| ism.dMCupp | 1.6 | Extinction index 100 |

| ism.norm_DD | 1.0 | Diffuse dust norm. factor |

| ism.Rdust | ([0.0, 2.0], log) | Radius of the diffuse dust (DD, pc) |

| ism.f_PAH | ([0.0, 1.0], lin) | DD fraction radiated by PAH |

| ism.dDDlow | 0.7 | DD extinction index 100 |

| ism.dDDupp | 2.0 | DD extinction index 100 |

| syn.alpha_syn | 0.75 | Spectral index |

| syn.nu_self_syn | 0.2 | Self-absorption frequency (GHz) |

| f_cal | ([-5.0, 0.0], log) | Calibration uncertainty |

Parameter GMC(s) with varied parameters Common parameter ranges Brief description age GMC2: ([6.0, 12.0]) ([6.0, 11.0]) Age of the MC sfh.tau_star GMC2: ([6.0, 12.0]) ([6.0, 11.0]) Characteristic timescale ism.R_MC GMC2: ([0.0, 1.7]), GMC8: ([0.0, 1.7]) ([0.0, 2.0]) Average radius of a MC ism.tau_esc GMC2: ([6.0, 12.0]) ([6, 11.0]) Stars’ escape time from MC sfh.psi_max GMC3: ([-2.0, 1.5]), GMC5: ([-2.0, 1.5]) ([-3.0, 1.5]) Maximum SFR, at ism.tau_star

3.2 CIGALE photometric SED fitting

In addition to the main results obtained from GalaPy, for comparison we also provide simultaneous UV-to-radio SED modeling with the recently updated CIGALE 2022.1 version (Yang et al., 2022). This software operates on the principle of energy balance, where energy attenuation in the UV-to-optical range is re-emitted in the infrared in a self-consistent manner. Its modular and parallelized design, along with its user-friendly interface, has made it a popular choice in the literature for estimating the astrophysical characteristics of various targets. Below, we provide a brief overview of the models employed to simulate the galaxy emission.

To construct the SEDs with CIGALE, we utilized the full photometric coverage available for our GMCs. The modeling was based on the widely-used Bruzual & Charlot (2003) SSPs, adopting the IMF of Chabrier (2003) and assuming a solar-like metallicity.

The stellar populations evolved using a delayed SFH with an additional burst component (Ciesla et al., 2015). This SFH approach is more realistic compared to the simple delayed model and has been demonstrated to minimize biases in the estimation of SFR and stellar mass (Schreiber et al., 2018). Additionally, the inclusion of the burst is consistent with the ALMA detections (Hamed et al., 2021, 2023). For the SFH parameters, we maintained flexibility in the age and the e-folding time of the main stellar population to avoid introducing artificial biases in the efficiency of the initial burst.

Dust attenuation was modeled following the Calzetti et al. (2000) attenuation law, allowing the color excess of the young stellar population to vary as a free parameter. Dust emission was a critical component of our SED modeling, given the extensive IR coverage, particularly from ALMA. We used the models provided by Draine et al. (2014). To ensure a good fit, we explored the parameter space for PAH fractions and the radiation field, Umin, aiming to minimize while keeping the models physically realistic. Considering the rich radio data available for the GMCs, we extended our UV-IR modeling to radio regime taking into account the

PL nature of the synchrotron spectrum and the ratio of the FIR/radio (qIR) correlation in the CIGALE fitting.

CIGALE minimizes the by measuring the difference between observed data and the model predictions, weighted by the uncertainties in the observations. The goal of minimization is to find the best-fitting model parameters that reduce this difference (Boquien et al., 2019).

The CIGALE modeling was performed in the rest frame, which is directly applicable to NGC 253, as no corrections were necessary. Additional details, including the addition of AGN-related parameters, are provided in Appendix A.

3.3 Stellar population fitting with starlight

GalaPy and CIGALE are used in the full SED fits (all wavelengths from UV to Radio), while starlight will be used for the optical data only to fit stellar population models. starlight has been successfully applied to fit the stellar component of a diverse range of galaxy types, such as low-luminosity AGN, Seyfert nuclei, and normal galaxies.

While traditionally used for optical spectra, we applied the latest version of the code, described by Werle et al. (2019), to fit simultaneously the combined MUSE and S-PLUS data (see Fig. 4), thus covering the 3,500–10,000 Å range. The combination of these datasets provides a comprehensive view of the galaxy’s stellar populations, spanning a wide range of wavelengths. In particular, the S-PLUS bands densely cover the highly informative region around the 4,000 Å break which falls outside the range of MUSE spectra that starts at 4,600Å.

starlight uses a chi-squared minimization technique to find the best-fit non-parametric combination of stellar populations of different ages and metallicities from a pre-defined library. This analysis allows us to estimate properties, such as mean age, metallicity, and extinction, as well as the velocity dispersion of the stellar component. The base is built from SSP models from the Charlot & Bruzual 2019 library models (Martínez-Paredes et al., 2023) using PARSEC evolutionary tracks (Chen et al., 2015) and a Chabrier IMF. A base of composite stellar population is built from the SSP models assuming constant SFRs in 16 logarithmically spaced age bins with 5 different metallicities. Extinction is modeled with two components: one applied to all populations () and an extra one applied exclusively to Myr stars ().

The list of parameters to fit includes the flux (or mass) fractions of the different populations, global and selective extinction, the velocity shift and velocity dispersion.

We have adjusted the weight scheme for the code used to extract residuals for H, [N II], [O III], and H by augmenting them around those lines. This modification allows a detailed examination on the contribution of stellar absorption features to these emission lines, compared to a general fit to the MUSE+SPLUS spectra/photometry. These lines will subsequently serve as input for diagnostic diagrams and to estimate the extinction affecting the emission line regions.

4 Results

In the following, we supplement our SED analysis with existing literature. Since the GMC selection was based on ALMA observations, our primary information source is the ALCHEMI results (Martín et al., 2021). After detailing the characteristics of the ten GMCs by dividing them in two main groups, we will compare our panchromatic results – derived from SED fitting – on star formation rates (SFRs) and histories (SFHs) with those obtained from pure-optical and pure-sub-mm/cm observations, that is, from monochromatic tracers such as the H and H40 emission lines and different infrared and radio continuum regimes or bands. This approach will help us understand the key limitations to consider when working with mono-wavelength datasets. For a more detailed description of our results in light of previous literature information and for each of the ten GMCs, we refer the reader to our Appendix B.

4.1 SED fitting

The wealth of archival data described in Sect. 2 does not always cover the ten GMCs. Only S-PLUS, Spitzer/IRAC, ALCHEMI, VLA L (1.5 GHz), and Ku (15 GHz) Bands fully cover the NGC253’s CMZ (see Table 2). EVLA Band X does not detect emission outside GMCs 3 to 6, similar to the case in VLA K (23.6 GHz) band. Also, the VLA C (4.9 GHz) Band does not detect emission in GMCs 1 and 2, and our aperture of 3″ is not fully covered by emission in GMCs 8–10, hence we discarded the latter contribution. From the above, we can say that the best-studied GMCs are GMCs 3 to 6, corresponding to the core of NGC253 and representing most of the star formation produced there (Bendo et al., 2015). It is worth saying that, in addition to the possible lack of continuum emission, the not imaged GMCs may fall below the detection limit of our ALMA Band 3 observations and the different centimeter bands mentioned above, the detection limit at 3 of EVLA Band X, and VLA Bands K and C are 2.410-2, 5.410-3, and 6.610-4 Jy, respectively.

In general, the GMC’s SED shapes, which can be seen in Fig. 3, are similar to what is found in local and high-redshift starbursts (e.g., Swinbank et al., 2010). These SEDs exhibit significant absorption in the near-UV and optical wavelength regimes (– Å), caused by an exceptionally large amount of dust. This leads to a substantial difference between the predicted and observed emissions (i.e., stellar emission with and without extinction), illustrated by the red and green lines in Fig. 3. At the mentioned wavelengths, the flux difference can reach up to four orders of magnitude (e.g., from mJy down to mJy in GMCs 4–6 at 104 ). The total extinction () derived from the stellar component exceeds 5.0 magnitudes in GMCs 3–6, based on analyses from GalaPy, CIGALE, and the Balmer lines (H and H; see Sect. 4.2.2).

Tables 5 and 6 respectively contain GalaPy and CIGALE results related to star-formation processes, such as the SFR, the stellar mass (), the characteristic timescale (), or the stellar age (Age). In addition, results on the gas and dust characteristics, the attenuation, the radiation field, the time for stars to escape from their parental MC (ism.tau_esc), and uncertainties of the model, to mention a few, are given in Tables 9 and 10 for GalaPy and CIGALE, respectively.

We summarize below the main characteristics of the molecular clouds studied here by dividing them basically in two different media. The central GMCs, numbered from 3 to 6 and the external ones: GMCs 1,2 and 7–10. We find strong differences among them in terms of stellar and dust masses, and star formation rates. Appendix B provides detailed information of individual GMCs.

GMC SFR Age [ yr-1] [log10 ()] [log10 (yrs)] [10-3] [log10 ()] [log10 (yrs)] 1 50 6.535 10.88 0.35 8.065 9.30 2 80 7.534 9.21 3.88 8.391 9.66 3 870 8.573 9.07 7.88 9.354 9.62 4 2740 8.850 7.48 20.84 10.132 8.54 5 6450 8.620 7.57 17.59 10.184 8.40 6 1870 8.605 8.17 12.87 9.602 8.56 7 220 8.156 8.50 8.12 8.903 9.39 8 110 7.837 9.24 4.45 8.533 9.76 9 90 7.752 9.12 4.53 8.605 9.73 10 50 7.581 9.55 3.31 8.507 9.64

GMC SFRINST SFR100Myr SFR10Myr Age [] [] [] [log10()] [log10(yrs)] [log10()] [log10()] [log10(yrs)] 1 20.763.19 23.273.77 20.953.20 6.700.07 8.150.30 6.700.03 7.870.11 9.418.88 2 31.023.67 26.377.05 31.803.62 7.170.06 8.320.28 7.170.00 8.100.12 9.528.63 3 262.0168.63 292.0553.19 264.8870.81 7.820.07 8.100.30 7.820.05 7.740.04 9.368.85 4 642.5032.13 446.8349.84 655.2432.76 8.500.02 8.390.30 8.500.00 8.160.00 9.548.55 5 1956.59129.59 204.0213.25 2024.70128.51 8.170.02 8.260.30 8.170.01 7.920.11 9.448.65 6 476.2049.31 509.4161.56 481.1251.15 7.940.06 8.230.30 7.940.00 7.930.00 9.448.85 7 191.8832.85 214.9834.37 193.5432.60 7.680.06 8.030.30 7.680.01 7.680.09 9.338.85 8 47.7211.49 46.499.52 49.3211.65 7.510.07 8.020.30 7.510.01 7.750.01 9.368.76 9 35.295.96 41.357.97 35.725.93 7.180.06 8.150.28 7.180.00 7.710.00 9.358.75 10 32.415.03 38.118.36 32.985.10 7.170.07 8.220.30 7.170.00 7.820.00 9.408.86

4.1.1 GMC characteristics

The Central Molecular Zone (CMZ) of NGC 253 can mainly be divided into two primary groups based on the physical and chemical properties found in their giant molecular clouds (GMCs) listed in Table 1: internal and external GMCs. The internal GMCs, corresponding to GMCs 3, 4, 5, and 6, are located in the very nuclear region of the CMZ, about 120 pc extension (see, e.g., the scale bar in Fig. 13), and are characterized by high densities, elevated temperatures, fast shocks likely triggered by a tremendous star formation activity (Bouvier et al., 2024; Bao et al., 2024). Conversely, the external GMCs encompass GMCs 1, 2, 7, 8, 9, and 10, located near (GMC 7) or fully immersed in the periphery of the internal bar. There, orbital intersections such as inner Lindblad resonances (Iodice et al., 2014), bar/spiral arm interactions –also known as interactions (Kim et al., 2012)–, and cloud-cloud collisions (Ellingsen et al., 2017, see their Sect. 4.3) take place (see, e.g., ellipses in Fig. 2). These GMCs are dominated by a lower-density molecular gas, as compared to the internal GMCs, and exhibit signatures of slow shocks (up to 30 km s-1) rather than intense stellar feedback. This division reflects significant dynamical and chemical variations across the CMZ, previously noted by ALCHEMI studies (e.g., Tanaka et al., 2024; Behrens et al., 2024; Harada et al., 2024).

The study by Harada et al. (2024) utilized ALMA observations to conduct a detailed survey of molecular lines, applying principal component analysis (PCA) to distinguish patterns of chemical excitation and physical conditions across the CMZ. Their results indicate that the internal GMCs (GMCs 3–6) exhibit strong emissions from dense gas tracers such as HCN and HC3N, along with radio recombination lines (RRLs), which are associated with active star formation and high-excitation regions (e.g., Bendo et al., 2015). In contrast, the external GMCs (GMCs 1, 2, and 7 to 9 in the work of Harada et al. (2024), which did not account for GMC 10) are characterized by tracers of slow shocks, such as CH3OH and an increment of HNCO over SiO (Meier et al., 2015; Humire et al., 2022), reflecting less energetic dynamical processes. The PCA revealed that molecular emission correlates strongly with dynamical features, with high-excitation species dominating the central regions, while shock tracers are more prevalent in the outskirts.

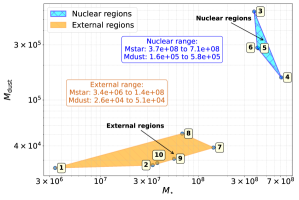

In the current analysis, the differentiation between internal and external GMCs is further supported by variations in star formation rate (SFR), stellar mass, and dust mass. The internal GMCs exhibit SFRs above 0.087 yr-1, as found by GalaPy, which provides an instantaneous SFR listed in the second column of Table 5, as well as greater stellar (third column; Table 5) and dust masses (; Table 9), consistent with the high-density, high-excitation environments described by Harada et al. (2024). For the sake of clarity, we provide a plot showing the dust mass, versus stellar mass in Fig. 5, they were obtained from GalaPy. In the latter figure, we label the ranges for these quantities for nuclear and external regions or GMCs. The internal or nuclear GMCs (GMCs 3-6) display stellar masses in the 3.7–7.110 range, and dust masses in the 1.6–5.810 range, in strong contrast to the external GMCs, where the stellar and dust masses range between 0.034–1.410 and 2.6–5.110, respectively.

The above indicates that the dust mass is the clearest distinction between the two primary groups, while the stellar mass, although enhanced in the internal GMCs, is only a factor of two larger in GMC 6 (internal) with respect to GMC 7 (external).

The external GMCs are also characterized by a lower SFR than the inner ones, with values in the 0.005–0.022 yr-1 range. These findings align with the chemical and dynamical distinctions previously observed in multiple ALCHEMI studies (e.g., Tanaka et al., 2024; Behrens et al., 2024; Harada et al., 2024), reinforcing the conclusion that the physical properties of the CMZ are tightly coupled with its molecular and dynamical characteristics.

4.2 Optical spectral fitting

We fit archival MUSE data (ID:0102.B-0078(A), PI: Laura Zschaechner) in the 4600–9350Å range with SPLUS photometric data using starlight (Cid Fernandes et al., 2005) in its latest version which is capable to fit spectra and photometry simultaneously (López Fernández et al., 2016; Werle et al., 2019).

To correct for the mismatch between spectroscopic and photometric fluxes, we scale MUSE spectra to match the iSDSS band flux of S-PLUS. The S-PLUS bands used for the fits are uJAVA, J0395, J0410 and J0430, iSDSS. the filter F0378 was not used to avoid contamination by [O II] 3727 emission. Of these, the blue ones are the most important, because they extend the MUSE coverage to the age sensitive 4,000 Å region.

The starlight fits to the MUSE spectra and the fitted S-PLUS photometric points for the ten GMCs are shown by the blue lines and the cyan points, respectively, in Fig. 4. Some important stellar absorption features are labeled in the top panels and indicated by vertical dashed green lines for all the GMCs. The outputs of the fitting are summarized in Table 10.

As is commonly known (see, e.g., Conroy, 2013a), low-mass stars dominate both the total mass and the number of stars in a galaxy, but they contribute only a small fraction to the overall light output, or bolometric luminosity, since young stars outshine older stars. This can be seen in the star formation histories per GMC, which are plotted in Fig. 6. Independent of the molecular cloud, light fraction is always shifted towards young stars, while the mass fraction is concentrated in old stars. For example, in GMC 5, while nearly 100% was already formed 10 Gyr ago 50% of the light comes from stars 30 Myr.

Also in Fig. 6, for GMC 5, we have over-plotted (in magenta) the normalized skewed Gaussian derived from the age-metallicity relation (AMR; see Appendix C), this same distribution was adapted to be cumulative (cAMR) and plotted (in yellow) in the same panel for GMC 5 of Fig. 6. GMCs 3 to 6 also show the estimated ages from super star clusters derived by Butterworth et al. (2024) in vertical dashed blue lines.

GalaPy (black) provides older stellar age estimations than averaged starlight values in GMC 10 and this happens because, although GalaPy is affected by the newest stellar production in the IR (the IR bump), it is not limited by ages of stellar templates, which is the case for starlight. Nevertheless, for all the other GMCs (GMCs 1–9), we observe that the stellar ages derived from GalaPy fall in between the old and new stellar populations that best fit the stellar contribution in the optical using starlight. This is more clearly seen in Fig. 19, where we plot, for all ten GMCs studied in this work, the average old and young stellar population ages from starlight, and the global stellar ages from GalaPy. Both codes agree in that GMC 4 is the youngest in the sample, with younger stellar populations in GMCs 3 to 7 and older ones located in GMCs 1, 2, and 8 to 10. In addition, in the same plot we added results from CIGALE, whose output delivers youngest ages in general with the youngest stellar burst in GMC 5, very close to the youngest burst in GMC 4 derived by GalaPy.

4.2.1 Emission line diagnostic diagrams

The fluxes of emission lines from the MUSE spectra were measured in the pure nebular spectra, obtained after the subtraction of the stellar population continuum from the observed spectra. The contribution of the stellar population was determined using the stellar population synthesis code starlight (Cid Fernandes et al., 2005).

These estimates were used to analyze the dominant ionization mechanism of the emitting gas in the galaxy. To do this, we used two diagnostic diagrams:

-

(a)

The [O III] /H versus [N II] /H diagnostic diagram proposed by Baldwin et al. (1981), commonly known as the BPT diagram. This diagram includes the theoretical separation between Hii-like and AGN-like objects proposed by Kewley et al. (2001) [K01], and the empirical star-forming limit proposed by Kauffmann et al. (2003) [K03]. The region between the theoretical and empirical limits is commonly referred to as the “composite region,” although there are claims against this designation (see below).

-

(b)

The WHAN diagram, namely, versus (Cid Fernandes et al., 2010), which is used to differentiate the nature of the ionization sources, classifying objects as star-forming, strong AGNs, weak AGNs, or retired galaxies. The line at represents the limit between weak and strong AGN emission. We note that in this diagram, he chosen log10([N II]/H; x-axis) limit to disentangle between SF and AGN gaseous ionization origin is normally taken from Stasińska et al. (2006) [S06] in the literature, although for NGC 253’s CMZ we can rely on K03 as there are no GMCs between S06 and K03 limits.

The results are shown in Fig. 7 where we extract the emission lines in our common 3 diameter aperture using archival MUSE observations (ID:0102.B-0078(A), PI: Laura Zschaechner). Interestingly, our GMCs do not occupy the regions in these diagrams that are typically associated with star-forming regions. Instead, they are located in what is often referred to as the “composite” zone, lying between star-forming and AGN-dominated areas. According to some studies, the latter behavior can happen in strong starburst, when stellar shocks are fast (e.g., Kewley et al., 2001).

However, given the lack of evidence for an actual AGN in NGC 253, and the fact that these line-ratios are observed well away from the nucleus, our GMCs are most likely not starburstAGN composites. Instead, we prefer to describe them as “starburstshocks” composites, where the observed line ratios are a mixture of star-formation and shocks from stellar winds and supernovae. Shocks are indeed known to be present in NGC 253 (Meier et al., 2015; Holdship et al., 2022; Humire et al., 2022; Behrens et al., 2022; Harada et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2023; Behrens et al., 2024; Bouvier et al., 2024; Bao et al., 2024), whereas there is extensive literature arguing against the presence of an AGN (e.g., Fernández-Ontiveros et al., 2009; Brunthaler et al., 2009; Müller-Sánchez et al., 2010).

From the SED perspective, a clear argument against the existence of an AGN is provided in Appendix A, where the AGN fraction, in Table 13, is negligible (7.5%) and also does not peak at GMC 5 as one might expect in the presence of an AGN. Although this behavior could potentially suggest the presence of a low-luminosity AGN (LLAGN), it is more plausibly interpreted as an artifact of CIGALE’s attempt to accurately fit the AGN-free SED. Further arguments specifically against the presence of an LLAGN can be found, for instance, in Mangum et al. (2019, their Sect. 7.1).

4.2.2 Attenuation estimations

The attenuation from dust in Hii regions can be estimated using the Balmer lines H and H by contrasting their observed ratios with their expected ratios without attenuation. The intrinsic H/H flux ratio is 2.86 under typical conditions of electron density ( cm-3) and temperature ( K), although variations in these conditions can change the ratio by up to 4% (Osterbrock & Ferland, 2006). The so called Balmer extinction is given by

| (2) |

where and for a Calzetti et al. (2000) reddening law. In the following, we will apply this method to the GMCs studied in this work by measuring for each region and estimating their respective attenuations.

For comparison, we also considered the attenuation model proposed by Charlot & Fall (2000), a widely used approach for estimating dust extinction in stellar populations. This method distinguishes between the contributions of young and old stellar populations, assigning different power-law attenuation slopes to each. The attenuation for young populations, attributed to birth clouds, is represented by , while that for older populations, associated with the ISM, is denoted as , as described in Eq. 4. According to this framework, stars are initially formed within interstellar birth clouds (BCs) and migrate to the ISM after approximately years. The transition between these two attenuation regimes occurs at a wavelength of 5,500 Å. In CIGALE, this model can be adopted using the dustatt_2powerlaws module. The functional form of the law is commonly expressed in the literature as:

| (3) |

where is the wavelength-dependent attenuation expressed as , with , and represents the attenuation in the V band. In practice, this translates to the following expression:

| (4) |

where is the overall attenuation at 5,500 Å that we assume to be unity for simplicity. The exponents and describe the slopes for the birth clouds and the ISM, respectively. In the implementation, the values for range from -0.69 to -0.9, while ranges from -0.75 to -0.3. We find these values starting from those commonly used in Charlot & Fall (2000) and also being influenced by other works that assume a -0.7 (an original assumption from C&F 2000) value for both stellar populations. Then, looking at our GalaPy-derived curves from the SED, we set values that better reproduce the observations.

We compute the attenuation curves over a wide wavelength range, from the near-UV to the near-infrared, using these parameter ranges. The curves are normalized at 5,500 Å to allow a consistent comparison. As shown in Fig. 8, the model’s attenuation curves are sensitive to the chosen values of for the Calzetti et al. (2000) attenuation law, which assumes a single attenuation slope for all stellar populations, and the values of and in the case of the Charlot & Fall (2000) models.

Table 7 lists the measured Balmer decrement, the corresponding , as well as the values obtained with CIGALE and starlight. As expected from the extremely red shape of the optical spectra (see Fig. 4), we obtain large values of : from 1 to 6 mag. The largest values are found for GMCs 3, 4, 5, and 6, which are closer to the galactic bar and in dense star-forming areas. We note, however, the very substantial uncertainties in (ranging from 10 to nearly 90%). These happen because of the weak emission, which is barely visible in most cases in Fig. 4.

Table 7 further lists the starlight results for the extinction. In the case of starlight the table gives , which we define as the average of the extinctions affecting all populations () and that affecting only those younger than 10 Myr (), weighting them by the fluxes of the respective components as derived from the fits. Again, the extinction values are large (1.8–5.7 mag), as expected from the redness of the optical continuum. The derived values are close to, but in general somewhat smaller than those derived from the Balmer decrement.

| GMC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mag] | [mag] | [mag] | ||

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| 4 | ||||

| 5 | ||||

| 6 | ||||

| 7 | ||||

| 8 | ||||

| 9 | ||||

| 10 |

In Table 7, we provide our results. For starlight, we list both the value of affecting all populations and the flux-weighted extinction considering both and the additional extinction () applied only to populations younger than 10 Myr to account for the dust in their birth clouds. Table 7 also lists the CIGALE values of , which differ from those derived from the Balmer lines, , by a 16% in median. On the other hand, starlight-based values also differ from those of by a median value of 27%.

The only GMC where exceeds is GMC 1. This discrepancy may suggest additional sources of attenuation, potentially linked to warm or dense dust. One possible explanation is the influence of strong shocks, which could sputter dust grains and enhance local dust densities. Supporting evidence for the presence of shocks in GMC 1 comes from its elevated SiO 5–4/HNCO (100,10–90,9) transition ratios observed at about 220 GHz (ALMA Band 6). This region shows the highest ratio values (about 2), as noted in the right panel of Fig. 11 in Humire et al. (2022). These elevated ratios are well-known tracers of strongly shocked gas, indicating a prevalence of strong (traced by SiO) over weak/mild shocks (traced by HNCO). Additionally, GMC 1 hosts methanol masers with the strongest deviations from LTE expectations among the 10 GMCs, as illustrated in the left panel of Fig. 13 in the same study. While these observations strongly point to the presence of shocks, they are not direct indicators of warm or dense dust. However, shocks may indirectly affect the dust environment by altering its spatial distribution or properties. Future studies are needed to assess whether gas and dust are tightly coupled in this region and to determine the extent to which shocks influence the observed attenuation.

We note that, even though the parameter was set to 3.1 in CIGALE, which corresponds to the typical value of the dust extinction law for the Milky Way (Calzetti et al., 2000), the differences between the resulting and any other attenuation-related parameter in Table 11 do not differ by that 3.1 factor from . The parameter controls the relationship between the total and the selective extinctions of starlight by dust. A higher value indicates that, as the amount of dust increases, it less affects the attenuation, something that may be clearer seen in the following expression: .

GalaPy derived attenuation curves are shown in Fig. 8, where curves indicate the attenuation in the visible band and legends show its value at 5500Å, on a linear scale, to be compared with starlight outputs (Table 10). The results from this code are normalize at that wavelength value. values following Calzetti et al. (2000) are also included for comparison. These values describe the relationship between the total amount of dust extinction and the amount of reddening it causes in the context of the Milky Way’s dust extinction curve and corresponds to the ratio between the total extinction and the color excess . Considering the ten GMCs studied, most values range between 6 and 9, far beyond the Galactic value of 3.1. Surprisingly, extreme values come from clouds at the boundaries of the CMZ, with the highest lying in GMC 1, 9, and 10, and the lowest value in GMC 2.

As a final remark, when comparing the different attenuation estimates, it is important to recognize that the gas attenuation (from the Balmer decrement) and stellar attenuation (from GalaPy, CIGALE, and STARLIGHT in our case) have distinct origins. Recent studies suggest that these two types of attenuation should become increasingly similar as the observed region ages (Li & Li, 2024). Although, we do not see a clear trend for attenuation differences between the ones derived from the Balmer decrement and those obtained from CIGALE, namely , taken from Table 7, versus derived stellar ages from either GalaPy or CIGALE (last columns of Tables 5 and 6, respectively), we do see a trend when comparing Attenuation differences between Balmer lines and the gas attenuation derived from the stellar continuum by starlight versus stellar ages derived by CIGALE. For an easy visualization of that finding, in Fig. 9 we present such a relation.

4.3 Star Formation Rates

4.3.1 Kennicutt relation

There are many ways to obtain the SFR from monochromatic emission. One of the most commonly used is the relation found by Kennicutt (1998) regarding H:

| (5) |

where is corrected for extinction using .

Fig. 12 shows a comparison between the SFR obtained from the above considerations and the one obtained from the SED fitting using GalaPy and CIGALE, while the dashed-red line indicates a one-to-one proportion. To create this plot we considered the attenuation of the H emission line derived SFR considering the , since it is expected to be the most accurate method: starlight and SED derived attenuation rely on the continuum level.

We notice that SFRs derived by GalaPy (red symbols in Fig. 12) tend to be larger than expected by the Kennicutt relation, this is an expected result as the H’s derived SFR corresponds to the stellar formation averaged over the last 10 Myr (see, e.g., Stroe et al., 2015). Interestingly, however, considering the 10 Myr and 100 Myr CIGALE’s averaged SFRs (grey symbols in Fig. 12), the Kennicutt relation is followed at a higher degree when considering 100 and not 10 Myr values (see Table 6), and is less dispersed in relation to the instantaneous SFR derived by CIGALE (SFRINST; blue symbols in Fig. 12).

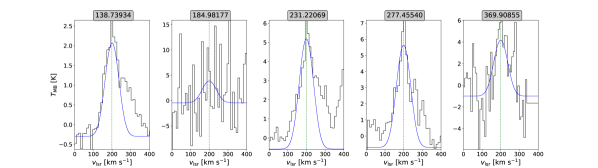

4.3.2 Radio recombination lines

There are several ways to estimate the star formation rate of an astronomical source. One of the most accurate methods not affected by dust extinction involves radio recombination lines (RRLs). Following the approach described by Bendo et al. (2015), where the H line at 99.02 GHz was utilized, we determined the SFR for the central nuclear regions (specifically GMCs 3 to 6). As shown in Figure 13, the SFR density per spaxel aligns with values obtained by GalaPy for the same regions where RRLs are detected. Our calculation, focusing on GMCs 3 to 6, within a 3″ aperture, yielded a value of 1.852 M⊙ yr-1 (refer to Table 9), which is consistent with the SFR of 1.730.12 reported by Bendo et al. (2015), considering uncertainties. We highlight that the SFR obtained by GalaPy corresponds to the instantaneous (i.e., current) SFR while RRLs are expected to also trace recent SF of the last 5–10 Myr (Scoville & Murchikova, 2013; Emig et al., 2020). It is worth noting that due to our 3″ aperture extraction, there is some overlap in the fluxes from GMCs 5 and 6. This overlap likely contributes to our estimations being at the upper limit of RRL estimations. However, our photometric extraction does not include fluxes between GMCs, as illustrated in Fig. 13. Considering a 9-aperture-radius SED involving some of the mentioned inner GMCs (GMCs 4 to 6), as it can be seen in the bottom inset of the left panel of Fig. 20 and considering Herschel PACS observations, we obtain a SFR of 1.620 M⊙ yr-1. After adding the SFR from GMC 3, which is not covered by the 9 aperture and is 0.087 M⊙ yr-1, we obtain a SFR for GMCs 3 to 6 of 1.707, also consistent with the results of Bendo et al. (2015). However, the latter should be taken as a lower limit because, although devoid of any slight overlapping issue between GMCs 5 and 6, the 9 aperture does not fully encompass GMC 4, as shown in the lower inset of Fig. 20’s left panel.

4.3.3 Radio cm continuum and FIR correlation

As summarized in Murphy et al. (2011), there are several SFR tracers in the wavelength range considered in this work. According to these authors, the 33GHz continuum emission is a reliable indicator of current star formation, as it primarily arises from thermal free-free emission. Although this frequency can sometimes be affected by rotating dust, this is not the case for NGC253 at the studied scales, as shown in the SEDs. We indeed find a strong correlation between the emission in the EVLA Ka Band, as originally published in Kepley et al. (2011), and the total SFR computed by GalaPy. Furthermore, accounting for scaling offsets, we also observe generally good correlations—close to a 1:1 correspondence—between cm tracers and the GalaPy results, as seen in Fig.10. The latter was obtained using the same approach as for the 33GHz, namely, by performing a linear regression in logarithmic space with all retrieved (E)VLA continuum images that detect at least four GMCs (see Table 5), aiming to obtain the best-fit assembly valid for the GMCs in the starburst galaxy NGC 253. A caveat should be noted, as different galaxy types (e.g., MW-like, dwarf galaxies, AGN hosts) may present different relationships. In this regard, an immediate prospect for the current work is to evaluate the different relations between SFR tracers.

Accounting for IR points as SFR tracers, shown in Fig. 11, we generally find a lower dispersion and higher quality of the fit in terms of mean R in relation to the radio bands. However, that is an artifact since we are not accounting for the error bars in any of the plots, which are larger in the x-axis, as can be seen in the Fig. Given that our FIR points are taken from the SED fit itself, they are not independent to the derived SFR, although we note larger dispersion when altering the SED points in other bands (not shown). The general conclusion that we can still obtain from the IR tracers is that the best ones correspond to the integrated IR emission between 8 and 1000 m, normally referred as total IR emission and the IR emission at 60 m.

We note that, contrary that for the case of optical lines, we do not assume a relation factor a priory, we only convert our mJy measurements to erg s Hz for an easy comparison between this study and the literature. For the mJy erg s Hz conversion we have assumed a distance of 3.5 Mpc to NGC 253 (Rekola et al., 2005).

5 Discussion

5.1 Reliability of our SED model along the FIR window

One of the critical, if not the most critical, challenges that astronomers have to face when attempting to fit a panchromatic SED at high angular resolution is the impossibility to acquire far infrared (FIR) observations at resolutions below 6. Current facilities in the regime, such as the James Webb (JWST) and Euclid telescopes, cover mainly the near-IR and mid-IR part of the electromagnetic spectrum, with the largest wavelength window ranging from 0.5 (Euclid) to 28 m (JWST). Indeed, only the JWST can keep angular resolutions below 0.8 at 28 m. However, the FIR bump primarily occurs at wavelengths larger than those, mainly from about 50 to 300 m.

While we made use of our well covered sub-mm regime, with ALCHEMI data, to fine-tune the Rayleigh-Jeans tail, at the emergence of the FIR bump on the radio side, and used VLT/NACO data at 11 and 18.7 m on the MIR side for GMCs 3–7, we know the caveat that this is likely not enough to properly ensure the fit on the IR bump itself, relying on our SED model extrapolations. This is why we further retrieved archival Herschel PACS observations selecting level 2.5 PACS images at 70, 100, and 160 m. While these FIR observations are not able to resolve the targeted GMCs, they are sufficient to fit emission from the inner part of the CMZ, covering at most GMCs 3 to 6 in the worst-case scenario (at 11.3), and partially covering GMCs 4 to 6 at 6 and 9 (see Appendix E for more information on this latter).

In Fig. 20 it can be noted that the far infrared peak agrees between the 3 aperture SED, devoid of FIR photometric points and the SED at 9, whose diffuse dust temperature, , of 68.833 K is in agreement to the ones of the covered GMCs (GMCs 4–6), as noted in Table 5. Specifically, we get estimations of 84.532, 67.929, and 63.318 K for GMCs 4, 5, and 6, respectively. All in all, this arguments in favor of our 3 apertures as the FIR bump and the SED shape in general peaks at a very similar point. It is worth noting that the SED shape is responsible for specific star formation rate estimates and, thus, for the stellar mass and SFR estimates as well (Conroy, 2013a).

Given the lack of FIR photometric points in the FIR regime at 3, our SED models experienced considerable freedom in this specific wavelength range. We found that GalaPy produced SED shapes that were closer, compared to CIGALE’s models, to those observed at 9, where Herschel PACS observations are available. Nevertheless, it is worth emphasizing that CIGALE performs well in fitting the SED of GMC 5 at 9 (which also includes GMCs 4 and 6), both with and without an AGN component, as discussed in Appendix A.

| GMC | sSFR (GalaPy) | sSFR (CIGALE) |

|---|---|---|

| [log10 yr-1] | [log10 yr-1] | |

| 1 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 | ||

| 6 | ||

| 7 | ||

| 8 | ||

| 9 | ||

| 10 |

5.2 Comparison to high-z dusty starbursts

The question of whether local starbursts can serve as analogues of primeval dusty galaxies at high redshifts () remains a topic of active debate. A useful parameter in this context is the dust-to-stellar mass ratio, which provides insight into the balance between dust production and destructive processes such as supernova-driven shocks and astration (Nanni et al. 2020, Donevski et al. 2020, Kokorev et al. 2021, Donevski et al. 2023, Witstok et al. 2023, Palla et al. 2024, Sawant et al. 2024).

To place the ISM conditions of NGC 253 into perspective against those of distant dusty galaxies, we compare the dust-to-stellar mass ratios () derived in this work to those inferred from ALMA observations of high- starbursts (Donevski et al. 2020, Salak et al. 2024, Sawant et al. 2024). Regardless of the SED fitting code used, all GMCs in NGC 253 exhibit relatively high dust-to-stellar mass ratios, with a median value of (values from CIGALE), or , if values from GalaPy are considered. These ratios are close to those observed in young dusty starburst galaxies in the distant Universe. Specifically, the average dust-to-stellar mass ratio is at (Donevski et al. 2020) and at (Sawant et al. 2024). A caveat in comparing the dust-to-stellar mass ratio found here with literature is in the method used to derive galaxy properties. Both in Donevski et al. (2020) and Sawant et al. (2024), the SED fitting is performed using CIGALE, which results in average lower values with respect to GalaPy, as also reported above.

Moreover, inferred attenuation values in the GMCs of NGC 253 are comparable to those observed in high- dusty starbursts but also significantly higher than those typically found in JWST-detected galaxies at (e.g., Nanni et al. 2020, Álvarez-Márquez et al. 2023, Markov et al. 2024). It is important to note that, despite their comparable ”dustiness,” GMCs in NGC 253 have , SFR and sSFR several orders of magnitude lower than their high- counterparts. In such low stellar mass regimes, dust production is generally expected to be dominated solely by stellar sources, such as Type II supernovae (Galliano et al. 2018, Sommovigo et al. 2020).

However, recent models suggest that dust production in young starbursts may be significantly diminished due to ISM removal in the presence of strong stellar outflows, similar to those observed in NGC 253. To reconcile the high dust-to-stellar mass ratios, these models propose efficient growth of large dust grains through ISM accretion in rapidly cooling gas within stellar outflows (Hirashita & Chen 2023, Donevski et al. 2023, Romano et al. 2024, Palla et al. 2024). While a detailed exploration of this intriguing possibility lies beyond the scope of this work, we note that the high dust-to-stellar mass ratios and attenuations observed in the GMCs may signal that NGC 253 is undergoing a shift in the dominant dust production mechanisms, as proposed by recent simulations (see e.g., Narayanan et al. 2024, also Schneider & Maiolino 2024 for a review).

6 Conclusions and Prospects

This study represents a significant step forward in understanding the CMZ of NGC 253, utilizing the first panchromatic SED analysis at a 51-pc resolution towards extragalactic regions. The integration of diverse modeling approaches, from GalaPy to CIGALE and starlight on the stellar continuum features, enabled a thorough characterization of physical properties such as star formation rates, dust and stellar masses, and attenuation effects across ten GMCs using both parametric and non-parametric models.

The integration of multi-wavelength SED modeling tools, such as GalaPy and CIGALE plus the integration of mono-wavelength tracers in the optical using starlight and the sub-mm using CASSIS, provided detailed insights into star formation histories, attenuation, and stellar population properties at different timescales. High extinction values (e.g., AV exceeding 5 magnitudes in internal GMCs) were robustly derived, aligning well with other methods and showcasing the importance of panchromatic approaches.

We summarize our main findings below.

-

1.

Dynamical and Chemical Diversity:

-

•

The Central Molecular Zone (CMZ) of NGC 253 exhibits significant dynamical and chemical distinctions between internal (nuclear) and external GMCs.

-

•

Internal GMCs (e.g., GMCs 3–6) are characterized by higher star formation rates (SFR), stellar masses, and dust masses, consistent with active star formation, high-excitation regions, and higher metallicities.

-

•

External GMCs (e.g., GMCs 1, 2, 7–10) display lower density, slower shocks, and chemical signatures indicative of less energetic processes as compared to the internal GMCs.

-

•

-

2.

Comparison of Internal vs. External GMCs:

-

•

Internal GMCs exhibit stellar masses in the range of and dust masses in the range of , both greatly surpassing (doubling) maximum values observed in external GMCs.

-

•

Specific star formation rates (sSFR) further illustrate these differences, with significantly higher activity in the nuclear regions.

-

•

-

3.

Insights from Age-Metallicity Relations:

-

•

Differences in stellar ages and metallicities highlight the varied evolutionary states of the studied GMCs.

-

•

-

4.

Emission Line Diagnostics:

-

•

The BPT and WHAN diagrams indicate shock signatures in the nuclear region of NGC 253, placing it in the composite zone. However, these shocks likely result from stellar winds and supernovae in the starburst environment, not from AGN activity.

-

•

-

5.

Star Formation, Panchromatic vs. Monochromatic Results:

-

•

We have found a strong 1:1 correlation between cm tracers and SED derived SFR values, being the 33 GHz (Ka) band the best among the available dataset. This is in line with previous works based on entire galaxy properties (e.g., Murphy et al., 2011), and is now confirmed at GMC scales. Additionally, we validate the effectiveness of RRLs (H40) as a SF tracer, although limited to the brightest sources (GMCs 3–6).

-

•

The current study provides a robust framework for leveraging spatially-resolved multi-wavelength datasets to investigate the interplay between star formation, gas dynamics, and attenuation in starburst galaxies. In addition, this work not only advances our knowledge of starburst environments but also serves as a benchmark for studying high-redshift galaxies, where similar extreme conditions prevail.

In the future, we plan to focus on several key directions to broaden the applicability of these findings. These include utilizing JWST instead of Spitzer observations, achieving aperture diameters as fine as 1″ in the mid-IR, enabling more detailed analyses of star-forming regions and/or augmenting the redshift regime for our potential targets. We plan to apply the same approach to other well-known starburst like M 82. Alternatively, we want to improve the robustness of our fit by restricting ourselves to very nearby galaxies where FIR data from Herschel can still resolve GMC-scale structures. Additionally, this framework has the potential to be extended to diverse systems, including Milky Way like galaxies, LINERs, ULIRGs, and AGN, to explore differences in star formation processes across various galactic environments. Lastly, focused studies of GMCs in our Galaxy will offer a critical baseline for contrasting extragalactic GMC properties, contributing to a thorough understanding of star formation under varying conditions.

| GMC | ism.R_MC | sfh.psi_max | ism.f_MC | ism.tau_esc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [K] | [log10 ()] | [log10 (pc)] | [] | [log10 ( yr-1)] | [log10 (yrs)] | ||

| 1 | 50.365 | 8.573 | 0.90 | 0.53 | -1.69 | 0.01 | 7.75 |

| 2 | 67.295 | 7.126 | 1.02 | 4.11 | -1.67 | 0.02 | 9.19 |

| 3 | 66.739 | 8.010 | 0.79 | 8.77 | -0.54 | 0.04 | 8.83 |

| 4 | 61.899 | 6.925 | 1.27 | 25.38 | 1.15 | 0.43 | 7.98 |

| 5 | 54.833 | 7.386 | 1.60 | 21.14 | 0.84 | 0.20 | 6.98 |

| 6 | 35.814 | 7.441 | 1.53 | 14.70 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 6.18 |

| 7 | 40.327 | 6.833 | 1.41 | 8.77 | -0.54 | 0.38 | 7.64 |

| 8 | 59.476 | 7.320 | 1.05 | 3.04 | -0.51 | 0.02 | 8.12 |

| 9 | 64.423 | 7.079 | 0.54 | 4.77 | -1.45 | 0.04 | 9.22 |

| 10 | 41.421 | 7.250 | 1.53 | 3.48 | -1.92 | 0.11 | 9.02 |

| GMC | ism.Rdust | ism.f_PAH | noise.f_cal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [K] | [log10 ()] | [log10 (pc)] | ||||

| 1 | 34.643 | 4.410 | 1.08 | 0.17 | -0.64 | 2.27 |

| 2 | 33.528 | 4.435 | 1.08 | 0.32 | -2.25 | 1.80 |

| 3 | 34.110 | 5.766 | 1.64 | 0.12 | -0.61 | 1.47 |

| 4 | 84.532 | 5.195 | 1.17 | 0.04 | -0.55 | 1.32 |

| 5 | 67.929 | 5.566 | 1.43 | 0.03 | -0.62 | 1.14 |

| 6 | 63.318 | 5.453 | 1.35 | 0.04 | -0.73 | 1.35 |

| 7 | 62.911 | 4.474 | 1.08 | 0.06 | -0.94 | 1.38 |

| 8 | 41.419 | 4.492 | 1.21 | 0.17 | -1.38 | 1.35 |

| 9 | 43.383 | 4.679 | 1.17 | 0.15 | -1.11 | 1.29 |

| 10 | 41.532 | 4.574 | 1.20 | 0.19 | -1.25 | 1.31 |

GMC adev Lumtot v0 x(0) 1 1.85 9.82 4.94 -2.41 107.86 2.12 3.85 0.00 2.12 8.95 9.79 0.06 0.15 2 2 234.68 5.27 -11.02 113.8 2.22 7.24 2.76 2.42 9.15 8.77 -0.07 -0.07 3 4.3 160.71 6.28 11.63 154.93 4.44 0 23.78 4.44 8.72 9.86 0.02 0.13 4 3.56 6241.17 6.23 1.37 83.82 3.35 5.77 40.23 5.67 7.33 7.22 0.22 0.17 5 3.46 229.04 6.35 -18.47 126.71 4.66 0 4.75 4.66 8.51 9.89 -0.09 0.26 6 3.03 251.04 6.05 -39.4 125.21 3.59 2.04 24.95 4.1 8.66 9.88 -0.11 -0.25 7 2.73 310.66 5.8 -62.53 133.2 1.85 3.94 28.56 2.97 8.57 9.82 0.46 0.54 8 2.77 40.41 5.63 -59.2 106.07 2.28 4.46 0.00 2.28 9.69 9.95 -0.4 -0.51 9 2.65 22.74 5.35 -56.9 116.32 1.84 4.22 0.00 1.84 9.57 9.78 -0.12 -0.18 10 2.14 74.93 5.01 -69.57 124.54 1.43 3.61 18.89 2.12 8.6 9.08 0.55 0.55

Acknowledgements