Robust violation of a multipartite Bell inequality from the perspective of a single-system game 111Mod. Phys. Lett. A 37, 2250082(2022)

Abstract

Recently, Fan et al. [Mod. Phys. Lett. A 36, 2150223 (2021)], presented a generalized Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt (CHSH) inequality, to identify -qubit Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger (GHZ) states. They showed an interesting phenomenon that the maximal violation of the generalized CHSH inequality is robust under some specific noises. In this work, we map the inequality to the CHSH game, and consequently to the CHSH* game in a single-qubit system. This mapping provides an explanation for the robust violations in -qubit systems. Namely, the robust violations, resulting from the degeneracy of the generalized CHSH operators correspond to the symmetry of the maximally entangled two-qubit states and the identity transformation in the single-qubit game. This explanation enables us to exactly demonstrate that the degeneracy is .

I Introduction

Quantum entanglement Schrödinger (1935); Amico et al. (2008); Horodecki et al. (2009); Hill and Wootters (1997); Wootters (1998); Torun and Yildiz (2019), brought about by the superpositionprinciple, puzzled many physicists in the early days of quantum theory. In the original work for Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) paradox in entangled states Einstein et al. (1935), Einstein and his collaborators proposed that quantum mechanics provides probabilistic results because of its incompleteness. In 1964, Bell proposed an inequality Bell (1964) to solve the EPR paradox under the assumptions of local reality and hidden variable theory. Such inequality and its generalized versions Das et al. (2017, 2018) revealed nonlocality Brunner et al. (2014); Scarani (2019); Gisin and Bechmann-Pasquinucci (1998); Ren et al. (2019); Reid et al. (2009); Mermin (1990); Ardehali (1992) in entangled states. The Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt inequality Clauser et al. (1969) is the most widely studied Bell inequality for two-qubit systems, which is written as

| (1) |

with () being measurement settings. It can be violated by all the two-qubit entangled pure states.

Researchers have tried to understand the nonlocality from the perspective of game theory van Dam (2000); Ji et al. (2008); Henaut et al. (2018). The author of Ref. van Dam (2000) setted up the so-called CHSH game to show the advantage of quantum strategies. There are two players, Alice and Bob, in the game who cannot communicate with each other. They share a two-qubit system and have measurement operators and respectively. Here, and are two input values. Let and represent the outcomes of Alice and Bob. When , the players win the game, with denoting modulo addition. It is directly to find the linear relationship between their success probability

| (2) |

and the expected value of .

Recently, Henaut et al. Henaut et al. (2018) introduced a single-player CHSH* game with two inputs and . Any strategy in the CHSH* game can be mapped to a strategy in the CHSH game with two-qubit maximally entangled states. Without loss of generality, let Alice and Bob share one of the Bell states, . The player of the CHSH* game, Carol, has a qubit in state . Alice and Bob apply arbitrary local unitary transformations and to their qubits, and then measure the Pauli operator on their qubits respectively. This is equivalent to the local measurement of on . Carol applies and on the state and measures on her qubit. Similarly, this represents the measurement of on . She wins the game when her outcome . The success probabilities of the two games are equal; i.e.,

| (3) |

which arises from the expected values

| (4) |

with and .

On the other hand, to distinguish -qubit Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger (GHZ) states, Fan et al. presented a generalized CHSH inequality in their very recent work Fan et al. (2021) . It is expressed as

| (5) |

and denote the tensor products of local observables for the first qubit. and represent two observables of the th qubit. The -qubit GHZ states can be identified by the maximal violations of the inequality. Besides, they found an interesting quantum phenomenon of robust violations of the generalized CHSH inequality, in which the maximal violation can be robust under some specific noises. Such phenomenon originates from the degeneracy of the largest eigenvalue of Bell-function .

In this work, we show the mapping between the CHSH* and CHSH games proposed by Henaut et al. Henaut et al. (2018) can be extended to the generalized CHSH inequality for -qubit case. The relations among the inequalities (and the CHSH* game) provide an explanation for the robust violations and give the degeneracy of . Namely, we map the -qubit Bell function to for the two-qubit case, and consequently to for the one-qubit system. For the -qubit GHZ states ( and for and ), the expected values satisfy when . The equality holds when the generalized CHSH inequality achieves the Tsirelson’s bound, i.e.

| (6) |

This equation is invariable under specific local unitary transformations on the two-qubit and -qubit Bell-functions, which corresponds to the identity operation on the single-qubit system. By using these invariance, we exactly demonstrate the degeneracy of , which causes the robust violations.

II The generalized CHSH inequality and games

We first introduce the mappings from to , where the measured quantum states are the GHZ states

| (7) |

and the Bell state . Unless explicitly stated otherwise, all the expected values in this paper are of the states , and corresponding to -, two- and one-qubit system. The local measurement operators in -qubit system can be written as

| (8) |

where is the vector of Pauli matrices, and denote the measurement direction of the th qubit. Fan et al. Fan et al. (2021) defined the measurement operators of Alice and Bob in (5) as

| (9) |

One can derive the first term of as

| (10) | ||||

Obviously, only the terms , and are contributed by the projections of the measurement operators in the subspace of .

For brevity, we ignore the cases: (i) ; (ii) ; (iii) when is odd; (iv) when is odd. These cases compose a zero measure set, and do not violate the generalized CHSH inequality (5). To connect the expected value to the two-qubit system in the state , we define the following two mappings. The first one uniquely leads to a single-qubit observable, for a given -qubit operator in (9), as

| (11) |

Take as an example. The Bloch vector , with and . The other vector is in the similar form. The second mapping projects the single-qubit observable in (9) onto the equator of Bloch sphere; i.e.,

| (12) |

with and . When is even, one can choose

| (13) |

while

| (14) |

when is odd, and obtain the two-qubit Bell function

| (15) |

corresponding to in (5).

The above measurement operators and can always be expressed as and , with and being two local unitary transformations. That is, any measurement of the Bell function in (5) can be mapped to a strategy in the CHSH game, and consequently to the CHSH* game according to the relation given by Henaut et al. Henaut et al. (2018). The two maps are constructed based on the fact that, the expected value of on the state is equivalent to the one of on the state . The two single-qubit operators, and , are in the form of (8), but the Bloch vector of is in the unit ball in general. Therfore, we introduce a normalization coeffieient in (11). Under these mappings, we have the two following theorems.

Theorem 1.

Proof.

The expected values and can be written as

| (16a) | |||

| (16b) | |||

The range of is . When , one has

| (17a) | |||

| (17b) | |||

Similarly, when , the greater-than signs in the four inequalities (17) become the less-than signs. Let us denote the normalization constants of and as and . They satisfy and .

When is even,

| (18) | ||||

Multiplying by weighting coefficients and summing up them, according to the inequalities (17a) one can find when . Evidenced by the same token, when ,

When is odd, one has

| (19) | ||||

When , according to the inequalities (17b), it is direct to obtain

| (20) |

The form of (10) leads to and . Consequently,

| (21) | ||||

Multiplying by weighting coefficients and summing up the terms in (19), according to the relations (20) and (21) one can find when . Similarly, when , This ends the proof.

∎

There are two corollaries of Theorem 1 as follows. (i) The maximal violations of the GHZ state cannot exceed the Tsirelson’s bound , which has been found in Ref. Fan et al. (2021). (ii) When the expected value for the GHZ state , the corresponding .

Theorem 2.

When the expected value for the GHZ state saturates the Tsirelson’s bound, , the Bloch vectors of the operators in and in (9) are restricted as follows three cases

| (22a) | |||||||

| (22b) | |||||||

| (22c) | |||||||

Only the case (iii) exists in the system with an odd .

Proof.

According to Theorem 1, requires . That is, . Either all of the Bloch vectors , with , are parallel to z axis, or perpendicular to z axis. This holds true for with . %ͬһ Blochʸ␣ͬ z ␣ͬ xyƽ

When is odd, also requires . Hence, the Bloch vectors of and in (14) are perpendicular to z axis. The ones of and should also be perpendicular to z axis, to enable to achieve . The correspondence in (14) leads to that only the case (iii) is allowed.

When is even, and cannot be simultaneously parallel to z axis. This is naturally derived from the fact that the measurement directions of and in (14) are perpendicular when . In brief, the three cases of the Bloch vectors, (i), (ii) and (iii), are possible when the GHZ state achieves the maximal violations of the generalized CHSH inequality, with being even. This ends the proof.

∎

III Robust Violations of the generalized CHSH inequality

III.1 Framework

In this section, we show that the above mappings provide an explanation for the quantum phenomenon of robust violations of the generalized CHSH inequality Fan et al. (2021). Based on the explanation, one can exactly demonstrate the degeneracy of the Bell function , which corresponds to the dimension of noises for robust violations.

According to the results in section II and Ref. Fan et al. (2021), when the -qubit Bell function , the corresponding , and consequently , reach . In addition, the corresponding terms in the three Bell functions are equal; i.e.,

| (23) |

with

| (24a) | |||

| (24b) | |||

One always can inset the unit operator, with being unitary, between the two unitary operators in , as . It is equivalent to a local unitary transformation on the two qubit system as

| (25) | ||||

This actually gives the symmetry operations of the Bell state , that

| (26) |

and the relation between different choices of observers achieving the maximal violation.

To preserve the equations (23) and the value of , the local unitary operator can only have some special forms, which we will list in the following part. For a given , the corresponding transformation of the -qubit system can be written as

| (27) |

where . At this point, note that, even if is odd. In addition, the set of is not unique. This is because the mapping from to is many-to-one. Similarly, the degree of freedom of in (25) also comes from the many-to-one relationship between and . Generally, is different with , which indicates the largest eigenvalue of is degenerate. Mixing or superposing with the states in the subspace does not affect . This is the quantum phenomenon of robust violations of Bell’s inequality for the GHZ state presented by Fan et al. Fan et al. (2021).

III.2 Degeneracy

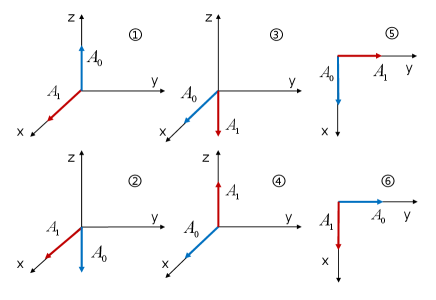

Then, we give the details of the local unitary transformations and degeneracy. According to their relationship between the Bloch vectors of and the z axis, there are six cases of the observers in , as shown in Fig. 1. Only the measurement directions (up to rotations about the z axis) of are plotted, since can be uniquely determined by when reaches the maximal violation. These six cases have a two-to-one correspondences with the three possible choices of the -qubit operators in Theorem 2 which are (i): ①, ②; (ii): ③, ④; and (iii): ⑤, ⑥.

According to the equivalence relations under the local unitary transformations on the -qubit system and the exchange between and , it is sufficient to consider only the degeneracy of corresponding to cases ① and ⑤. For the case ①, there are six types of the unitary operator to consider, corresponding to the six cases in Fig. 1 as the final states of . However, only two types of for the case ⑤ need to be considered, corresponding to the final states in ⑤ and ⑥. This is because, it is equivalent to the one in case ①, if the -qubit operators can be transformed by into the cases (i) or (ii) in Theorem 2. As show in Fig. 2, for fixed and , one can derive the unitary operators by requiring . We remark that, the initial and final directions of two Bloch vectors can uniquely determine a unitary operator, up to a phase factor which does not affect value of in (27).

Case ①.– The case ① exists only in the system with an even . The angles in can always be adjusted to zero by local rotations about the z axis, which transforms into simultaneously. In addition, the single-qubit operators in , have even minus signs. These minus signs can be removed by qubit flips without affecting the corresponding . Therefore, one can choose the initial observables as

| (28) |

To construct the local unitary transformations and , we introduce three sets of unitary operators as

| (29a) | ||||||||

| (29b) | ||||||||

| (29c) | ||||||||

For an arbitrary superscript , one can check the -qubit GHZ state has a symmetry as

| (30) |

where denotes the direct product of on the first qubits and is a phase factor. This can be regarded as an extension of the symmetry of the Bell state in (26).

The operator , transforming the initial into the case $\nu$⃝, can be universally written as

| (31) |

with . According to the correspondences between the six cases and the three possible choices in Theorem 2, there are two alternative forms of as

| (32) |

with and . Applying them onto and and requiring , one can easily obtain the two conditions on , as

| (33) |

and the number of in being even.

Then, are eigenstates of the inital , with the same eigenvalue as . By utilizing the forms of in (32) and in (31), one can derive these states in three steps : (1) rotations about the z axis with and ; (2) , including the ones in , and ; (3) the even number of or factored out from . The state is invariant under the operations in the first two steps, because of the condition (33) and the symmetry (30). Consequently, are equivalent to the results of multiplied by even number of or . Since is invariant under even number of , the degenerate states are given by qubit flips in pairs (i.e., application of even number of ) on . The degeneracy can be directly derived as

| (34) |

Case ⑤.– One can always adjust the angles in to zero by using local rotations about the z axis, which transform into and into simultaneously. Then, the initial observables can be choose as

| (35) |

with and .

In order to express in a similar way as the case ①, we define

| (36a) | |||||

| (36b) | |||||

Similarly, the -qubit GHZ state has a symmetry as

| (37) |

with and being a phase factor. The operators transforming the initial and into the case $\mu$⃝, can be written as

| (38) | |||

| (39) |

with and .

We define the sets , and , with and being its complementary set. The elements of are the subscripts of with , and ones of are for . Applying the operators (38) onto and and requiring , one can easily obtain

| (40) |

and

| (41) |

The latter condition is on the initial observables , which is a difference with the case ①. The states can be derived by following the same three steps in the case ①, which lead to

| (42) |

with being the Pauli operator of the -th qubit.

For a fixed , reaches the maximal violations, only when the initial satisfies the condition (41). Therefore, the number of , with which the condition (41) is satisfied, gives the degeneracy of the largest eigenvalue of . Then, the maximum degeneracy in the case ⑤ is , which can be obtained based on the following facts. The condition (41) cannot be fulfilled simultaneously by a subset of and its complementary set, which sets as the upper limit on the degeneracy. A simple construction to reach the upper limit is that, and .

Example.– An arbitrary choice of the operators and reaching the maximal violation of can always be transformed into the above two cases by local unitary operations. The degenerate subspace can also be derived by the same local unitary operations on the above results. We show these by using the example with provided in Ref. Fan et al. (2021), which belongs to the case ⑤.

The parameters of the observables and are given by , and . Then, . The operators can be adjusted into the simple form (35) by using and on the third and forth qubits. These lead to , , and . Then, the subsets of , with which the condition (41) are fulfilled, are given by

| (43) |

Applying and onto , one obtains the four degenerate states as

| (44) | ||||

which are the same as the results in Ref. Fan et al. (2021).

IV summary

In summary, we relate the two recent topics in the area of Bell-nonlocality, which are the robust violations of Bells inequality of the GHZ states Fan et al. (2021) and the single-qubit quantum game Henaut et al. (2018). Namely, we present the mapping from the generalized CHSH inequality, to distinguish the GHZ states constructed by Fan et al. Fan et al. (2021) to the CHSH game, and consequently to the single-qubit CHSH* game Henaut et al. (2018). These relationships provide an explanation for the robust violations of the generalized CHSH inequality in -qubit systems. The identity transformation in the CHSH* game, corresponds to the symmetry of the two-qubit Bell state, and further leads to the local unitary transformations generating the degenerate subspace of the -qubit Bell function. An arbitrary superposition or mixture in the subspace leads to the same expected value of the Bell function, which is the quantum phenomenon of robust violations. Based on the explanation, we exactly prove that the maximal degeneracy is . It would be interesting to extend the mapping among the systems with different numbers of subsystems to explore more topics in the area of Bell-nonlocality and entanglement, such as the identification of W states.

Acknowledgements.

This work was supported by the NSF of China (Grants No. 11675119 and No. 11575125).References

- Schrödinger (1935) E. Schrödinger, Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 31, 555 (1935).

- Amico et al. (2008) L. Amico, R. Fazio, A. Osterloh, and V. Vedral, Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 517 (2008).

- Horodecki et al. (2009) R. Horodecki, P. Horodecki, M. Horodecki, and K. Horodecki, Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 865 (2009).

- Hill and Wootters (1997) S. Hill and W. K. Wootters, Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 5022 (1997).

- Wootters (1998) W. K. Wootters, Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2245 (1998).

- Torun and Yildiz (2019) G. Torun and A. Yildiz, Phys. Rev. A 100, 022320 (2019).

- Einstein et al. (1935) A. Einstein, B. Podosky, and N. Rosen, Physical Review 47, 777 (1935).

- Bell (1964) J. S. Bell, Physics 1, 195 (1964).

- Das et al. (2017) A. Das, C. Datta, and P. Agrawal, Phys. Lett. A 381, 3928 (2017).

- Das et al. (2018) A. Das, C. Datta, and P. Agrawal, arXiv: 1809.05727 (2018).

- Brunner et al. (2014) N. Brunner, D. Cavalcanti, S. Pironio, V. Scarani, and S. Wehner, Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 419 (2014).

- Scarani (2019) V. Scarani, Bell Nonlocality (Oxford Univ. Press, 2019).

- Gisin and Bechmann-Pasquinucci (1998) N. Gisin and H. Bechmann-Pasquinucci, Physics Letters A 246, 1 (1998).

- Ren et al. (2019) C. Ren, T. Feng, D. Yao, H. Shi, J. Chen, and X. Zhou, Phys. Rev. A 100, 052121 (2019).

- Reid et al. (2009) M. D. Reid, P. D. Drummond, W. P. Bowen, E. G. Cavalcanti, P. K. Lam, H. A. Bachor, U. L. Andersen, and G. Leuchs, Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1727 (2009).

- Mermin (1990) N. D. Mermin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 1838 (1990).

- Ardehali (1992) M. Ardehali, Phys. Rev. A 46, 5375 (1992).

- Clauser et al. (1969) J. F. Clauser, M. A. Horne, A. Shimony, and R. A. Holt, Phys. Rev. Lett 23, 880 (1969).

- van Dam (2000) W. van Dam, Ph.D. thesis, University of Oxford (2000).

- Ji et al. (2008) S.-W. Ji, J. Lee, J. Lim, K. Nagata, and H.-W. Lee, Phys. Rev. A 78, 052103 (2008).

- Henaut et al. (2018) L. Henaut, L. Catani, D. E. Browne, et al., Phys. Rev. A 98, 060302 (2018).

- Fan et al. (2021) X.-Y. Fan, J. Zhou, H.-X. Meng, C. Wu, A. K. Pati, and J.-L. Chen, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 36, 2150223 (2021).