Quantum Monte Carlo sign bounds, topological Mott insulator and thermodynamic transitions in twisted bilayer graphene model

Abstract

We show that for magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene (TBG) away from charge neutrality, although quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) simulations suffer from the sign problem, the computational complexity is at most polynomial at certain integer fillings. For even integer fillings, this polynomial complexity survives even if an extra inter-valley attractive interaction is introduced, on top of Coulomb repulsions. This observation allows us to simulate magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene and to obtain accurate phase diagram and dynamical properties. At the chiral limit and filling , the simulations reveals a thermodynamic transition separating metallic state and a correlated Chern insulator – topological Mott insulator (TMI) – and the pseudogap spectrum slightly above the transition temperature. The ground state excitation spectra of the TMI exhibit a spin-valley U(4) Goldstone mode and a time reversal restoring excitonic gap smaller than the single particle gap. These results are qualitatively consistent with the recent experimental findings at zero-field and filling in -BN nonaligned TBG devices.

Introduction.— Magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene (TBG) has attracted great attention in recent years, as it hosts a variety of nontrivial phases beyond semi-classical or band-theory description [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41]. To theoretically characterize these flat bands and correlated quantum phases, tight-binding [2, 5] and continuous (BM) [3] models has been developed. In this study, we focus on the continuous-model approach, which avoids the challenge to construct localized orbitals that preserves all the symmetries [42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47]. By projecting long-range Coulomb interactions onto the moiré flat bands with proper quantum metric, such projected Hamiltonian has been studied using mean-field approximations [20, 48, 31, 49]. At certain limits, exact analytical solution has also been obtained [50, 51, 52, 53, 54]. On the numerical side, the charge neutrality point has been studied using sign-problem-free momentum-space quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) simulations [55, 56, 57]. However, away from the charge neutrality point, due to the arising of the sign problem, such simulations have not yet been performed.

Although the sign problem often implies exponential computational complexity, it is worthwhile to emphasize that not all sign problems cause such severe damage. Very recently, a much more mild type of sign problem has been demonstrated, where the computation complexity scales as a polynomial function of the system size, known as polynomial sign problem [58, 59].

In this Letter, we study the sign problem in TBG flat bands. Utilizing the sign bound theory [60], we prove that TBG flat bands at even integer fillings, or arbitrary integer fillings in the chiral limit, exhibit (at most) polynomial sign problem. This observation allows us to utilize QMC methods to study fillings away from charge neutrality, away from the chiral limit, and/or in the presence of extra attractive interactions on top of the Coulomb repulsion (See Tab. 1 for details).

To demonstrate this new approach, we performed large-scale QMC simulations to examine the chiral limit at filing (we denote the fully empty/filled flat bands as and charge neutrality as ). At , this model can be solved exactly [51, 53, 56], and the exact solution reveals that at , the system is a correlated Chern insulator – a topological Mott insulator (TMI) [61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66] – with Chern number . Upon raising the temperature, the insulating state shall “melt” into a metal and the time-reversal symmetry shall be recovered. However, our knowledge about this finite-temperature phase transition is very limited. Because the sign problem is only polynomial, QMC simulations become a highly efficient tool to study this system, from which three different phases/states are observed (1) a metal phase with time-reversal symmetry at high temperature , (2) a time-reversal invariant pseudo-gap phase at intermediate temperature and (3) a low-temperature TMI phase at . Here, is a crossover temperature scale and is the critical temperature of a second order phase transition, at which the time-reversal symmetry is spontaneously broken. We further show that the TMI phase only breaks the time reversal symmetry, while spins remain disordered due to thermal excitations of gapless spin fluctuations. This absence of spin order/polarization is in direct contrast to quantum Hall states where electron spins are polarized due to Zeeman splitting and thus spin fluctuations are gapped. In the discussion section, we establish the connection and consistency between our simulations and recent experimental studies on TMI phases in -BN nonaligned TBG devices [41].

BM model and projected interaction.— We utilize the BM model and project interactions between fermions to the moiré flat bands. The BM model Hamiltonian [3] for the valley takes the following form where and mark the two Dirac points in the valley from layers and respectively. and are the inter-layer tunnelings with matrixes , and where and are the intra- and inter-sublattice inter-layer tunneling amplitudes. are the reciprocal vectors of the moiré Brillouin zone (mBZ), and . For control parameters, we set for the chiral limit, and for non-chiral model, we set eV following Refs. [67, 50, 55, 57]. Here, is the twisting angle and is the lattice constant of monolayer graphene.

For interactions, in addition to the Coulomb repulsion, here we have the option to include one more interaction term and the sign problem will still remain polynomial.

| (1) |

The first term in () is the Coulomb interactions, and the second term introduces repulsive interactions for fermions in the same valley and attractions between the two valleys, which can be introduced as a phenomenology term describing inter-valley attractions [68, 69, 70, 71, 72]. At , this model recovers the standard TBG model with Coulomb repulsions. When is turned on, the inter-valley attraction favors inter-valley pairing and could stabilize a superconducting ground state. The normalization factor in is with being the linear system size of the system. and cover the whole momentum space, is the filling factor and represent layer/sublattice, valley, spin indices, respectively. The mometum dependence for non-negative and is unimportant to polynomial sign problem. Here, for simplicity, we set with being a non-negative constant and for , we use Coulomb interaction screened by single gate in our simulation where is the distance between graphene layer and single gate, is the dielectric constant. We then project the interactions to the moiré flat bands (See SM [73]) and use the projected Hamiltonian to carry out sign bounds analysis and QMC simulations.

Polynomial sign bounds.— In QMC simulations, the expectation value of a physical observable is measured as , where and are the weight and the expectation value for the configuration . Instead of summing over all configurations, a QMC simulation samples the configuration space using the probability . In sign-problem-free QMC simulations, for all and an accurate expectation value can be obtained by only sampling a small number of configurations – the importance sampling, and this number scales as a power-law function of the system size. However, for many quantum systems, can be negative or even complex, and thus to obtain an accurate expectation value, it requires to sample a large number of configurations, which usually scales as an exponential function of the system size [74].

It is worthwhile to emphasize that the sign problem doesn’t always lead to an exponentially high computational cost. To measure the severity of the sign problem, here we use the average sign , where is the absolute value of the real part of . For physical partition function , this average sign is between and , and means that the system is sign problem free, while smaller means severer sign problem. In a -dimension quantum systems that suffers from the sign problem, where the inverse temperature, indicating that the number of configurations needed in QMC simulations scales as an exponential function of the space-time volume. For polynomial sign problem, although (i.e., the system does suffer from the sign problem), is a polynomial function of the system size, and thus the number of configurations needed only scales as a power-law function of the system size.

Although the average sign can be easily measured in QMC simulations, it usually doesn’t have a simple analytic formula. To estimate the numerical cost to overcome the sign problem, we utilize the sign bound defined in Ref. [60]. As proved in Ref. [60], is the lower bound of (i.e., ). Thus, if the sign bound scale is a power-law function of the system size, the sign problem is (at most) polynomial. Remarkably, the low temperature sign bound in moiré flat bands can be easily calculated by counting ground state degeneracy, which can be obtained using SU(4) and SU(2) Young diagram as employed in Refs. [50, 51, 56] (See SM for details [73]).

Details about this calculation are shown in the SM and the conclusions are summarized in Tab. 1. At charge neutrality (), moiré flat bands with Coulomb interactions () is known to be sign problem free [55, 56], and thus the sign bound is . Here, we further prove that adding inter-valley attractions () to the chiral system doesn’t cause sign problem either (). Away from charge neutrality, sign problem arises, but it is polynomial at certain integer fillings. For Coulomb repulsion (), the sign problem is polynomial at any (even) integer fillings at (away from) the chiral limit. When inter-valley attractions are introduced (), even integer fillings at the chiral limit also have polynomial sign bound.

| Filling() | Chiral() | Non-chiral() | Chiral() |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ✗ | ✗ | ||

| ✗ | ✗ | ||

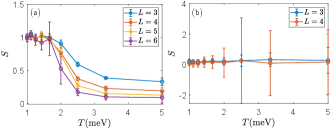

To further verify the polynomial sign problem summarized in Tab. 1, we directly calculate and in QMC simulations at various filling , and compare them with the exact formula of the sign bound obtained at integer fillings. As shown in Fig. 1, is always larger or equal to as expected, and the sign bound at integer filling indeed converges to the exact solution. The peak in at integer (or even integer) fillings indicates that the sign problem is less severe and QMC simulations have a faster convergence at these fillings. The location of these peaks are fully consistent with the polynomial sign problem summarized in Tab. 1. The only exceptions are and of Fig. 1(a), where the sign problem is polynomial but the figure doesn’t exhibit visible peaks. This is because the power-law function here has high powers and , which requires higher resolution (longer simulation time) to show clear distinction from exponential functions.

Chiral limit at and .— With the polynomial sign bound obtained, here we discuss the QMC results as a function of temperature for the chiral limit filling case in this section. In the QMC simulation, we observe a thermal phase transition with pseudogap spectrum and spontaneous time reversal symmetry breaking, which is of immediate relevance to the recent experimental finding of correlated Chern insulators at zero-field and filling in -BN nonaligned TBG devices and its relatively high Curie temperature of K [41].

At low temperature limit for , exact solution at expects degenerate ground states with Chern number , and [51, 53, 56]. In the large system size limit , the number of ground states scales as for and for [73]. Due to the higher number of ground state degeneracy, thermal fluctuations shall stabilize the state as the thermal equilibrium state at low temperature via the order by disorder mechanism [75]. This low-temperature state breaks spontaneously the time-reversal symmetry, but this symmetry breaking process as a function of temperature is unknown.

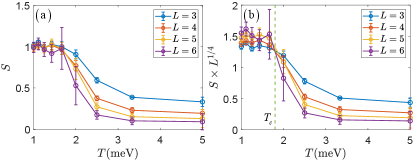

Our QMC simulation at finite temperature reveals this process. To probe the time-reversal symmetry breaking, we use the Chern band polarization as the order parameter, , where are the fermion occupation number operators of Chern bands. The correlation function of this order parameter is plotted in Fig. 2, , and scaling analysis reveals a second order phase transition at meV, below which the time-reversal symmetry is spontaneously broken, similar to what was observed at with real-space effective models [62, 63, 59]. At low temperature, approaches , indicating that the Chern number is , instead of . In Fig. 2(b), we rescale the axis as using the 2D Ising exponents and , and the cross point at meV marks the critical temperature.

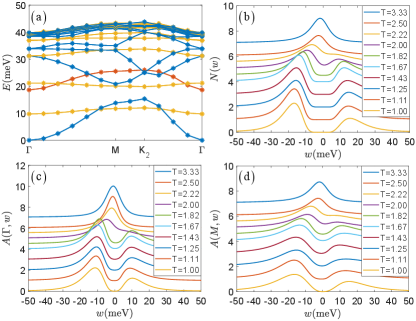

Such a spontaneously generated Chern insulator is of both theoretical and experimental interesting as in the temperature range of , it only breaks the time reversal symmetry but not the spin-valley U(4) continuous symmetry. In contrast to quantum Hall states, where fermion spins are polarized due to Zeeman splitting, spin degrees of freedom doesn’t form any order in this TMI phase and the spin SU(2) symmetry is preserved. To better demonstrate this point, we follow the method in Ref. [52] and analytically compute the spectrum of single-particle and charge-neutral excitonic excitations at . As shown in Fig. 3(a), single particle excitations (red stars) are fully gaped, indicating an insulating state. To restore the time-reversal symmetry, it requires to move fermions from + Chern bands to - Chern bands (or vice versa). However, such particle-hole excitations are fully gapped (yellow stars in Fig. 3(a)), and thus thermal fluctuations at low cannot restore the time-reversal symmetry. In contrast, particle-hole excitations between spin-valley bands with the same Chern number (blue starts) are gapless. These excitons describe spin SU(2) and spin-valley SU(4) fluctuations, and any spin or spin-valley order would be destroyed by these gapless excitations at any finite temperature.

We note that the energy scale of single particle gap is larger than the gap of time-reversal-restoring excitons [Fig. 3(a)], indicating that time-reversal symmetry breaking is probably more vulnerable to thermal fluctuations in comparison to single particle excitations. To probe this physics, we employ the stochastic analytic continuation (SAC) method upon the QMC imaginary time data of the Green’s function to extract the real-frequency single-particle spectra [76, 77, 78, 79]. Such QMC+SAC scheme has been successfully employed in many quantum many-body systems [80, 81, 82, 83, 84] including TBG and other moiré systems [55, 57, 71] and compared well with exact solutions and various spectroscopic experiments [78, 85, 86, 87, 88].

The obtained local density of states (LDOS) and the single particle spectral functions and are shown in Fig. 3(b-d), respectively. From them, one sees that slightly above the meV, at meV, the spectra indeed develop a pseudogap shape at both momenta and . Below , the spectra are fully gapped and the system is an interaction-driven topological Mott insulator [61, 62, 63] with no spin polarization and Chern number . The pseudogap behavior at , is certainly beyond mean-field description of the system, which would require the gap opens exactly at the transition, and is the manifestation of the intricate competition between the single-particle, collective excitations (such as the excitons) and thermal fluctuations in the morie system. Our LDOS results at low temperature with the asymmetric spectral weights, are also consistent with STM experiment at [11].

Discussion.— The experimental observation of the zero-field Chern insulators in TBG, at and with [41], clearly posts the question of how to understand the rich physics in pristine TBG systems, but it is known that the model level computations taking into account of the strong interaction and topological ingredient of the flat band wavefunctions at finite temperature, are notoriously challenging. Here we find the way out by using the fermion sign bounds theory [60], upon which we prove for Coulomb interaction and chemical potential projected on flat bands TBG model, all integer fillings at chiral and even integer fillings at non-chiral cases have either no sign problem or polynomial sign bounds in their QMC simulations. The similar behavior also retains when projected effective attraction is introduced for chiral even integer fillings.

This new approach allows us to unbiasedly compute the physical properties of the model at finite temperature. For , the numerical results are fully consistent with experimental observations, including spontaneous time-reversal symmetry breaking, Chern number , and the asymmetric in LDOS. For , the simulation reveals a pseudo gap phase. This result is consistent with the observation of insulating-like behavior at [11]. This pseudo gap phase would be an interesting subject for further experimental studies, which will help us better understand the phase transition and mechanism that drives the time-reversal symmetry breaking in moiré flat bands.

Acknowledgements.

Acknowledgements.—We thank Wang Yao for discussions on the related topic. XZ, GPP, BBC and ZYM acknowledge support from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong SAR of China (Grant Nos. 17303019, 17301420, 17301721, AoE/P-701/20 and 17309822), the K. C. Wong Education Foundation (Grant No. GJTD-2020-01), and the Seed Funding “Quantum-Inspired explainable-AI” at the HKU-TCL Joint Research Centre for Artificial Intelligence. We thank HPC2021 system under the Information Technology Services and the Blackbody HPC system at the Department of Physics, the University of Hong Kong for their technical support and generous allocation of CPU time.References

- Lopes dos Santos et al. [2007] J. M. B. Lopes dos Santos, N. M. R. Peres, and A. H. Castro Neto, Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 256802 (2007).

- Trambly de Laissardière et al. [2010] G. Trambly de Laissardière, D. Mayou, and L. Magaud, Nano Lett. 10, 804 (2010).

- Bistritzer and MacDonald [2011] R. Bistritzer and A. H. MacDonald, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 12233 (2011).

- Lopes dos Santos et al. [2012] J. M. B. Lopes dos Santos, N. M. R. Peres, and A. H. Castro Neto, Phys. Rev. B 86, 155449 (2012).

- Trambly de Laissardière et al. [2012] G. Trambly de Laissardière, D. Mayou, and L. Magaud, Phys. Rev. B 86, 125413 (2012).

- Rozhkov et al. [2016] A. Rozhkov, A. Sboychakov, A. Rakhmanov, and F. Nori, Physics Reports 648, 1 (2016), electronic properties of graphene-based bilayer systems.

- Cao et al. [2018a] Y. Cao, V. Fatemi, S. Fang, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, E. Kaxiras, and P. Jarillo-Herrero, Nature 556, 43 (2018a).

- Cao et al. [2018b] Y. Cao, V. Fatemi, A. Demir, S. Fang, S. L. Tomarken, J. Y. Luo, J. D. Sanchez-Yamagishi, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, E. Kaxiras, et al., Nature 556, 80 (2018b).

- Xie et al. [2019] Y. Xie, B. Lian, B. Jäck, X. Liu, C.-L. Chiu, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, B. A. Bernevig, and A. Yazdani, Nature 572, 101 (2019).

- Lu et al. [2019] X. Lu, P. Stepanov, W. Yang, M. Xie, M. A. Aamir, I. Das, C. Urgell, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, G. Zhang, et al., Nature 574, 653 (2019).

- Kerelsky et al. [2019] A. Kerelsky, L. J. McGilly, D. M. Kennes, L. Xian, M. Yankowitz, S. Chen, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, J. Hone, C. Dean, et al., Nature 572, 95 (2019).

- Da Liao et al. [2019] Y. Da Liao, Z. Y. Meng, and X. Y. Xu, Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 157601 (2019).

- Yankowitz et al. [2019] M. Yankowitz, S. Chen, H. Polshyn, Y. Zhang, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, D. Graf, A. F. Young, and C. R. Dean, Science 363, 1059 (2019).

- Tomarken et al. [2019] S. L. Tomarken, Y. Cao, A. Demir, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, P. Jarillo-Herrero, and R. C. Ashoori, Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 046601 (2019).

- Cao et al. [2020] Y. Cao, D. Chowdhury, D. Rodan-Legrain, O. Rubies-Bigorda, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, T. Senthil, and P. Jarillo-Herrero, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 076801 (2020).

- Nuckolls et al. [2020] K. P. Nuckolls, M. Oh, D. Wong, B. Lian, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, B. A. Bernevig, and A. Yazdani, Nature 588, 610 (2020).

- Soejima et al. [2020] T. Soejima, D. E. Parker, N. Bultinck, J. Hauschild, and M. P. Zaletel, Phys. Rev. B 102, 205111 (2020).

- Chatterjee et al. [2022] S. Chatterjee, M. Ippoliti, and M. P. Zaletel, Phys. Rev. B 106, 035421 (2022).

- Khalaf et al. [2020] E. Khalaf, N. Bultinck, A. Vishwanath, and M. P. Zaletel, arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.14827 (2020).

- Xie and MacDonald [2020] M. Xie and A. H. MacDonald, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 097601 (2020).

- Khalaf et al. [2021] E. Khalaf, S. Chatterjee, N. Bultinck, M. P. Zaletel, and A. Vishwanath, Science Advances 7 (2021).

- Pierce et al. [2021] A. T. Pierce, Y. Xie, J. M. Park, E. Khalaf, S. H. Lee, Y. Cao, D. E. Parker, P. R. Forrester, S. Chen, K. Watanabe, et al., Nature Physics 17, 1210 (2021).

- Liao et al. [2021] Y.-D. Liao, X.-Y. Xu, Z.-Y. Meng, and J. Kang, Chinese Physics B 30, 017305 (2021).

- Rozen et al. [2021] A. Rozen, J. M. Park, U. Zondiner, Y. Cao, D. Rodan-Legrain, T. Taniguchi, K. Watanabe, Y. Oreg, A. Stern, E. Berg, et al., Nature 592, 214 (2021).

- Zondiner et al. [2020] U. Zondiner, A. Rozen, D. Rodan-Legrain, Y. Cao, R. Queiroz, T. Taniguchi, K. Watanabe, Y. Oreg, F. von Oppen, A. Stern, et al., Nature 582, 203 (2020).

- Saito et al. [2021] Y. Saito, F. Yang, J. Ge, X. Liu, T. Taniguchi, K. Watanabe, J. Li, E. Berg, and A. F. Young, Nature 592, 220 (2021).

- Park et al. [2021] J. M. Park, Y. Cao, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, and P. Jarillo-Herrero, Nature 592, 43 (2021).

- Kwan et al. [2021] Y. H. Kwan, Y. Hu, S. H. Simon, and S. A. Parameswaran, Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 137601 (2021).

- Da Liao et al. [2021] Y. Da Liao, J. Kang, C. N. Breiø, X. Y. Xu, H.-Q. Wu, B. M. Andersen, R. M. Fernandes, and Z. Y. Meng, Phys. Rev. X 11, 011014 (2021).

- Kang et al. [2021] J. Kang, B. A. Bernevig, and O. Vafek, Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 266402 (2021).

- Liu and Dai [2021] J. Liu and X. Dai, Phys. Rev. B 103, 035427 (2021).

- Schindler et al. [2022] F. Schindler, O. Vafek, and B. A. Bernevig, Phys. Rev. B 105, 155135 (2022).

- Brillaux et al. [2022] E. Brillaux, D. Carpentier, A. A. Fedorenko, and L. Savary, Phys. Rev. Research 4, 033168 (2022).

- Song and Bernevig [2022] Z.-D. Song and B. A. Bernevig, Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 047601 (2022).

- Lin et al. [2022a] J.-X. Lin, Y.-H. Zhang, E. Morissette, Z. Wang, S. Liu, D. Rhodes, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, J. Hone, and J. Li, Science 375, 437 (2022a).

- Bhowmik et al. [2022] S. Bhowmik, B. Ghawri, N. Leconte, S. Appalakondaiah, M. Pandey, P. S. Mahapatra, D. Lee, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, J. Jung, et al., Nature Physics , 1 (2022).

- Huang et al. [2022] T. Huang, X. Tu, C. Shen, B. Zheng, J. Wang, H. Wang, K. Khaliji, S. H. Park, Z. Liu, T. Yang, et al., Nature 605, 63 (2022).

- Zhang et al. [2022a] S. Zhang, X. Lu, and J. Liu, Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 247402 (2022a).

- Herzog-Arbeitman et al. [2022] J. Herzog-Arbeitman, A. Chew, D. K. Efetov, and B. A. Bernevig, Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 076401 (2022).

- Andrei and MacDonald [2020] E. Y. Andrei and A. H. MacDonald, Nature Materials 19, 1265 (2020).

- Stepanov et al. [2021] P. Stepanov, M. Xie, T. Taniguchi, K. Watanabe, X. Lu, A. H. MacDonald, B. A. Bernevig, and D. K. Efetov, Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 197701 (2021).

- Song and Bernevig [2021] Z.-D. Song and B. A. Bernevig, arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.05865 (2021).

- Po et al. [2018a] H. C. Po, L. Zou, A. Vishwanath, and T. Senthil, Phys. Rev. X 8, 031089 (2018a).

- Koshino et al. [2018] M. Koshino, N. F. Q. Yuan, T. Koretsune, M. Ochi, K. Kuroki, and L. Fu, Phys. Rev. X 8, 031087 (2018).

- Kang and Vafek [2018] J. Kang and O. Vafek, Phys. Rev. X 8, 031088 (2018).

- Po et al. [2018b] H. C. Po, H. Watanabe, and A. Vishwanath, Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 126402 (2018b).

- Po et al. [2019] H. C. Po, L. Zou, T. Senthil, and A. Vishwanath, Phys. Rev. B 99, 195455 (2019).

- Liu et al. [2021a] S. Liu, E. Khalaf, J. Y. Lee, and A. Vishwanath, Phys. Rev. Research 3, 013033 (2021a).

- Zhang et al. [2020] Y. Zhang, K. Jiang, Z. Wang, and F. Zhang, Phys. Rev. B 102, 035136 (2020).

- Bernevig et al. [2021a] B. A. Bernevig, Z.-D. Song, N. Regnault, and B. Lian, Phys. Rev. B 103, 205413 (2021a).

- Lian et al. [2021] B. Lian, Z.-D. Song, N. Regnault, D. K. Efetov, A. Yazdani, and B. A. Bernevig, Phys. Rev. B 103, 205414 (2021).

- Bernevig et al. [2021b] B. A. Bernevig, B. Lian, A. Cowsik, F. Xie, N. Regnault, and Z.-D. Song, Phys. Rev. B 103, 205415 (2021b).

- Bultinck et al. [2020] N. Bultinck, E. Khalaf, S. Liu, S. Chatterjee, A. Vishwanath, and M. P. Zaletel, Phys. Rev. X 10, 031034 (2020).

- Vafek and Kang [2020] O. Vafek and J. Kang, Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 257602 (2020).

- Zhang et al. [2021a] X. Zhang, G. Pan, Y. Zhang, J. Kang, and Z. Y. Meng, Chinese Physics Letters 38, 077305 (2021a).

- Hofmann et al. [2022] J. S. Hofmann, E. Khalaf, A. Vishwanath, E. Berg, and J. Y. Lee, Phys. Rev. X 12, 011061 (2022).

- Pan et al. [2022a] G. Pan, X. Zhang, H. Li, K. Sun, and Z. Y. Meng, Phys. Rev. B 105, L121110 (2022a).

- Ouyang and Xu [2021] Y. Ouyang and X. Y. Xu, Phys. Rev. B 104, L241104 (2021).

- Pan et al. [2022b] G. Pan, H. Lu, H. Li, X. Zhang, B.-B. Chen, K. Sun, and Z. Y. Meng, arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.07133 (2022b).

- Zhang et al. [2022b] X. Zhang, G. Pan, X. Y. Xu, and Z. Y. Meng, Phys. Rev. B 106, 035121 (2022b).

- Raghu et al. [2008] S. Raghu, X.-L. Qi, C. Honerkamp, and S.-C. Zhang, Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 156401 (2008).

- Chen et al. [2021] B.-B. Chen, Y. D. Liao, Z. Chen, O. Vafek, J. Kang, W. Li, and Z. Y. Meng, Nature Communications 12, 5480 (2021).

- Lin et al. [2022b] X. Lin, B.-B. Chen, W. Li, Z. Y. Meng, and T. Shi, Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 157201 (2022b).

- Shen et al. [2020] C. Shen, Y. Chu, Q. Wu, N. Li, S. Wang, Y. Zhao, J. Tang, J. Liu, J. Tian, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, R. Yang, Z. Y. Meng, D. Shi, O. V. Yazyev, and G. Zhang, Nature Physics (2020).

- Liu et al. [2021b] X. Liu, C.-L. Chiu, J. Y. Lee, G. Farahi, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, A. Vishwanath, and A. Yazdani, Nature communications 12, 1 (2021b).

- Huang et al. [2020] M. Huang, Z. Wu, J. Hu, X. Cai, E. Li, L. An, X. Feng, Z. Ye, N. Lin, K. T. Law, et al., arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.05615 (2020).

- Bernevig et al. [2021c] B. A. Bernevig, Z.-D. Song, N. Regnault, and B. Lian, Phys. Rev. B 103, 205411 (2021c).

- Ge and Liu [2013] Y. Ge and A. Y. Liu, Phys. Rev. B 87, 241408 (2013).

- Roldán et al. [2013] R. Roldán, E. Cappelluti, and F. Guinea, Phys. Rev. B 88, 054515 (2013).

- Yuan et al. [2014] N. F. Q. Yuan, K. F. Mak, and K. T. Law, Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 097001 (2014).

- Zhang et al. [2021b] X. Zhang, K. Sun, H. Li, G. Pan, and Z. Y. Meng, arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.10018 (2021b).

- An et al. [2020] L. An, X. Cai, D. Pei, M. Huang, Z. Wu, Z. Zhou, J. Lin, Z. Ying, Z. Ye, X. Feng, R. Gao, C. Cacho, M. Watson, Y. Chen, and N. Wang, Nanoscale Horiz. 5, 1309 (2020).

- [73] The detailed QMC implementation of the model, the analyses of the polynomial sign behavior, excitations from exact solution and supplemental figures are given in this Supplemental Material .

- Pan and Meng [2022] G. Pan and Z. Y. Meng, arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.08777 (2022).

- Henley [1989] C. L. Henley, Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2056 (1989).

- Sandvik [1998] A. W. Sandvik, Phys. Rev. B 57, 10287 (1998).

- Beach [2004] K. Beach, arXiv preprint cond-mat/0403055 (2004).

- Sandvik [2016] A. W. Sandvik, Phys. Rev. E 94, 063308 (2016).

- Syljuåsen [2008] O. F. Syljuåsen, Phys. Rev. B 78, 174429 (2008).

- Sun et al. [2018] G.-Y. Sun, Y.-C. Wang, C. Fang, Y. Qi, M. Cheng, and Z. Y. Meng, Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 077201 (2018).

- Ma et al. [2018] N. Ma, G.-Y. Sun, Y.-Z. You, C. Xu, A. Vishwanath, A. W. Sandvik, and Z. Y. Meng, Phys. Rev. B 98, 174421 (2018).

- Wang et al. [2021] Y.-C. Wang, M. Cheng, W. Witczak-Krempa, and Z. Y. Meng, Nature Communications 12, 5347 (2021).

- Jiang et al. [2022] W. Jiang, Y. Liu, A. Klein, Y. Wang, K. Sun, A. V. Chubukov, and Z. Y. Meng, Nature Communications 13, 2655 (2022).

- Zhou et al. [2022] C. Zhou, M.-Y. Li, Z. Yan, P. Ye, and Z. Y. Meng, Phys. Rev. Research 4, 033111 (2022).

- Shao et al. [2017] H. Shao, Y. Q. Qin, S. Capponi, S. Chesi, Z. Y. Meng, and A. W. Sandvik, Phys. Rev. X 7, 041072 (2017).

- Zhou et al. [2021] C. Zhou, Z. Yan, H.-Q. Wu, K. Sun, O. A. Starykh, and Z. Y. Meng, Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 227201 (2021).

- Li et al. [2020] H. Li, Y. D. Liao, B.-B. Chen, X.-T. Zeng, X.-L. Sheng, Y. Qi, Z. Y. Meng, and W. Li, Nature Communications 11, 1111 (2020).

- Hu et al. [2020] Z. Hu, Z. Ma, Y.-D. Liao, H. Li, C. Ma, Y. Cui, Y. Shangguan, Z. Huang, Y. Qi, W. Li, Z. Y. Meng, J. Wen, and W. Yu, Nature Communications 11, 5631 (2020).

I Supplemental Material for

Quantum Monte Carlo sign bounds, topological Mott insulator and thermodynamic transitions in twisted bilayer graphene model

II QMC simulation

We introduce momentum space QMC method and fermion sign bounds theory briefly here following [55, 60]. Starting from flat band Hamiltonian

| (2) |

Here are the band indexes and is the so called form factor which is defined as the overlap of two eigen functions of bands at momenta and valley . Discarding the flat band dispersion (take the flat band limit), truncating the summation over band index and only keeping the two flat bands, we arrive at the final model Hamiltonian above to carry out sign bounds analysis and QMC simulations.

According to the discrete Hubbard-Stratonovich transformation, , where is a small constant, , , and , we can rewrite the partition function as,

In the last line we replace by for simple. Here is the imaginary time index with step , and are four-component auxiliary fields where is the amount of momentum points we consider. According to Ref. [67, 55], we only keep momentum points within length of reciprocal vector .

Generally, average of any observable can be written as,

| (4) |

Here and , respectively. We see as possibility weight and as sample value for configuration . Then Markov chain Mento Carlo can compute this .

But here is not non-negative for all configurations, we need do reweighting to derive a non-negative weight as a well-defined possibility.

| (5) |

The final numerator is the measurement with reweighting possibility distribution and the denominator is the well-known average sign. By noticing , we can define the lower bounds of sign as , which is also a well-defined observable expressed by partition functions of two systems . We can discuss properties of partition functions by measuring sign bounds, and we also can forecast average sign behavior by analyzing partition functions. This is the brief spirit of fermion sign bounds theory [60].

One useful result can be derived from the observation of all operators are unitary, so that for Green’s function at valley defined as

| (6) |

we have , so that . With this knowledge, we can measure Chern band polarize correlation function for auxiliary field according to

| (7) | |||||

where we use in to label different Chern bands. One should be careful that the definition of Chern bands will exchange in Hamiltonian when involving the other valley.

III Zero ground state energy

Zero ground state energy is important for sign bound analysis. We will introduce what is the sufficient conditions for zero ground state energy. At chiral limit in Chern basis, form factor is diagonal about Chern bands and . If there is no attraction (), in Chern basis

| (8) |

We define for convenience here. For a certain integer filling tuned by , we can find a ground state with whole Chern bands occupied by noticing a state satisfying for any must be the ground state for this positive semi-definite Hamiltonian.

| (9) |

Here mean filled Chern band, valley and spin indexes. One just requires the amount of filled bands is equal to to acquire zero energy ground state. This means all integer filling from 0 to 8 have zero energy ground state when .

With finite attraction , we need one more satisfied restriction to obtain zero energy ground state. Explicitly, this requirement is

| (10) |

Here mean filled Chern band, spin indexes in valley and are filled Chern band, spin indexes in valley . This restriction actually requires the same amount of filling bands in opposite valleys, which rules out odd integer filling cases at .

For non-chiral case, cannot be promised. The zero energy ground state requirement becomes

| (11) |

This means one needs full fill even opposite Chern bands, which corresponds to even integer fillings. These zero ground state energy states will be the necessary condition for sign bounds analysis below.

IV Ground state degeneracy and sign bounds

Symmetry for no attraction () chiral system is U(4)U(4) according to [50, 51], where each U(4) corresponds to spin-valley freedom with the same Chern number bands sector. We use Young diagram for SU(4) to compute ground state degeneracy of different integer fillings. The ground state wave function irreducible representation for filling from 0 to 4 corresponding to 2 spins, 2 valleys within Chern bands sector can be expressed as Young diagram below respectively

N

The amount of normal Young tableau for SU(4) symmetry calculated by hook length formula [51, 56] are

| (12) |

By the way, the SU(2) Young diagram for have the same shape with the SU(4) above, but the amounts of normal Young tableau are different

| (13) |

Now we are ready to count the total degeneracy for all integer filling from 0 to 8 (corresponding to from -4 to 4) for chiral no attraction () TBG model by using SU(4) Young diagram.

| (14) |

When we consider , the degeneracy with power of for different fillings can be seen as . Because the degeneracy for our reference system ( case where there is no sign problem) is , we can see the other integer filling have different polynomial sign bounds decay according to as . This is the first column result in our main text Tab. I.

One can verify the involving attraction case () will break the U(4)U(4) to U(2)U(2)U(2)U(2), where original spin-valley U(4) is broken into two spin U(2). By introducing filling the same amount of bands in opposite valleys restriction for zero energy ground states, we can write valley label explicitly for a given and use the SU(2) Young diagram results above to count the degeneracy of even integer fillings now

| (15) |

At large , sign bounds with attraction () at chiral even integer filling are written as , which is the result of the third column in our main text Tab. I.

It is well studied that non-chiral condition breaks U(4)U(4) into one U(4). We can count the ground state degeneracy of case by SU(4) Young diagram

| (16) |

This gives the second column result of Tab. I in the main text, which are sign bounds for non-chiral large case.

V Excitations from Exact solution

To give an intuitive understanding for finite temperature physics, we compute the single particle, two kinds of charge-neutral excitonic exciations following the method in Ref. [52]. Below, we first prove the single particle excitation states and charge neutral excitation states form closed orthogonal subspaces separately for the chiral no attraction () Hamiltonian we use. Then, we derive the eigen excitation states by diagonalizing the Hamiltonian in the subspace.

We choose one full-filling Chern bands ground state as where filled spin-valley bands labeled by and empty bands labeled by . By defining raising operators and their Hermitian conjugate linking filled spin-valley bands and empty spin-valley bands in Chern number subspace

| (17) |

we can check these operators commute with and also with the Hamiltonian. The commutation relations between these operators are

| (18) |

For raising between empty bands or full bands, those operators will not change the state and only give a constant and . We can then conclude all orthogonal ground states can be expressed based on and raising operators in a form below

| (19) |

Here are non-negative integers. The reason why we can write down this form is basically commutation between and will be which belongs to and the rest part after commutation will be which does not change the state and each will change the particle number while keeping momentum conservation in two bands so that different particle number distribution or different momentum conservation way states are orthogonal.

Now, we would like to check the orthogonal and close property for single particle excitation subspace . Here is not necessarily full-filled bands because bands can be partially filled in . Noticing is single particle Kronecker product state, orthogonality can be easily checked by Wick’s theorem. To be specific, only full contraction can give non-zero result where is a constant. And close property can also be checked according to

| (20) | |||||

This means only projects such a single particle excitation state to linear combination of single particle excitation states. Then one can diagonalize in this subspace to derive eigen single particle excitation. It is interesting to notice that the single particle excitation has nothing to do with the constant because this constant does not contribute to the commutation relation. Then the single particle excitation here will be exactly same for any integer chemical potential where it has zero energy and the single hole excitation is exactly the same with particle due to particle hole symmetry. This is consistent with STM experiment where LDOS slowly change with [11]

For charge neutral two particle excitation or , one need to exclude self-contraction within one side which gives but not as we want. For , this can be excluded automatically because will force contraction at the same side to be zero. For , only when , contraction at the same side can happen. If we ignore this one point then the left states again form an orthogonal and close subspace

| (21) | |||||

VI Supplemental figures

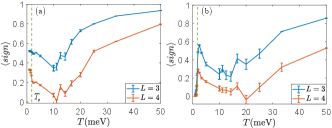

We list supplemental figures here. The converging behavior of average sign with temperature at chiral case is shown in Fig. 4(a). One can see at simulation temperature meV which the FIG. 1 in the main text used, the sign converge to the finite value both for . In contrast, for non-chiral case as shown in Fig. 4(b), the average sign shows the usual exponential decay at low temperature. It is also worth to notice that the topological phase transition temperature corresponds to a local curvature maximum of the average sign, which should be the case because the second-order derivative of sign bounds corresponds to second-order derivative of partition function where there should be a divergence for second-order phase transition. For finite size system, this divergence is captured by a local curvature maximum. Besides, above the phase transition temperature at non-chiral case as shown in Fig. 4(b), we can see there is also an anomalous lift of average sign as the lift at chiral. We speculate at this temperature, the fluctuation between different Chern bands is allowed so that the distinction between chiral and non-chiral is fuzzy. The entropy coming from huge degeneracy of chiral case contributes to the lift of the partition function as well as the average sign.

We also measure the Chern band polarization correlation function at chiral to confirm the Chern number keeps zero here as shown in Fig. 5(b), in contrast with the chiral case in Fig. 5(a) which is the case discussed in the main text.