Proton correlations and apparent intermittency in the UrQMD model with hadronic potentials

Abstract

It is shown that the inclusion of hadronic interactions, and in particular nuclear potentials, in simulations of heavy ion collisions at the SPS energy range can lead to obvious correlations of protons. These correlations contribute significantly to an intermittency analysis as performed at the NA61 experiment. The beam energy and system size dependence is studied by comparing the resulting intermittency index for heavy ion collisions of different nuclei at beam energies of , and GeV. The resulting intermittency index from our simulations is similar to the reported values of the NA61 collaboration, if nuclear interactions are included. The observed apparent intermittency signal is the result of the correlated proton pairs with small relative transverse momentum , which would be enhanced by hadronic potentials, and this correlation between the protons is slightly influenced by the coalescence parameters and the relative invariant four-momentum cut.

I INTRODUCTION

The exploration of the properties of the Quark Gluon Plasma (QGP) QGP1 ; QGP2 ; QGP3 and the phase structure of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) QCD1973 are the main objectives in relativistic heavy-ion collisions (HICs). Lattice QCD calculations at vanishing baryon chemical potential () determined a chiral crossover transition at MeV PRD71034504 ; Lattice ; PRD90094503 . Various theoretical investigations suggest that at finite baryon chemical potential and temperature, there could be a critical end point (CEP) in the QCD phase diagram 1stptcep1 ; 1stptcep2 ; 1stptcep3 ; 1stptcep4 . In order to explore the QCD phase diagram at finite net-baryon density, one tries to vary the temperature and baryon chemical potential of the nuclear matter created in HICs by changing the colliding energy and size of the colliding nuclei as well as the centrality, leading to different freeze-out conditions in and whitepaper ; SPSC-P-330-ADD-4 ; SCAN1 .

A non-monotonic behavior of fluctuation of observables is expected as a signal for the CEP PRL835435 ; PRL852072 ; PRL95182301 ; PLB633275 ; PRL102032301 ; sspma011012 . To investigate the phase transition and search for the CEP in HICs, a lot of analyses on fluctuations were done. For example, the analysis of event-by-event fluctuations of integrated quantities like the net-baryon number, electric charge, and strangeness, in particular their higher order cumulants NST281122017 ; prd96074510 ; prd101074502 ; prc101034915 ; pp583 ; prl126092301 . In addition, the analysis of local power-law fluctuations of the net-baryon density NA49SFM ; Local has drawn much attention. It can be detected through the measurement of the scaled factorial moments (SFMs) in transverse momentum space within the framework of a proton intermittency analysis SFM1 ; SFM2 ; Antoniou2005 ; Antoniou2006 . During the last decade, NA49 and NA61 performed a systematic search for critical fluctuations utilizing an intermittency analysis in central A+A collisions NA49prc81 ; Davis2002 . An indication of power-law fluctuations, in the transverse momentum phase space of protons at mid-rapidity in the central (0-12.5% ) Si+Si collisions at 158 GeV/, has recently been presented NA49SFM . In addition, a non-trivial intermittency effect was shown in a preliminary analysis of 40Ar+45Sc collisions at 150 GeV/ NA61 ; Davisapb .

A more indirect interpretation of recent STAR data also suggested a non-trivial intermittency index which cannot be described by a pure cascade simulation of the Ultra-relativistic Quantum Molecular Dynamics (UrQMD) model, and therefore warrants further investigation plb801135186 ; appburqmd . In this work, effects of hadronic potentials on the intermittency behaviour in HICs will be evaluated by a systematic scan in collision energy and system size within a modified version of the UrQMD model with and without hadronic potentials.

II Methodology

In order to investigate the non-statistical fluctuations and quantitatively understand the intermittent behavior in interactions, a technique based on the scaled factorial moments (SFMs) measurement was first introduced by Bialas and Peschanski SFM1 ; SFM2 . Here, momentum space is partitioned into equal-size bins and the SFMs are defined as:

| (1) |

where is the number of equally sized bins in which the D-dimensional space is partitioned, is the number of particles in the -th bin, the angular brackets denote an average over bins and events and is the rank of the moment.

For a critical system, the fluctuations of the order parameter are self-similar Vicsek , and the SFMs scale with the number of bins. In other words, if the dynamical fluctuations are self-similar in nature in the limit of small bin size, the SFMs are expected to increase with bin size following a power law. This effect is called intermittency, and can be quantified by this dependence:

| (2) |

The exponent is the so called intermittency index, which not only characterizes the strength of the intermittency, but also correlates with to the anomalous fractal dimension of the system Antoniou2006 . Many investigations suggest that one can explore the possible critical region of the QCD matter by using an intermittency analysis NA49SFM ; Antoniou2006 ; NA49prc81 ; plb801135186 ; CriticalReg . Universality class arguments associate the power-law behaviour of the SFMs with a specific exponent in case of the chiral condensate as order parameter Antoniou2005 and for the net-baryon density as order parameter Antoniou2006 ; NA49SFM .

Since such an analysis of higher order SFMs requires a large amount of data one usually only considers the second scaled factorial moment (SSFMs) in transverse momentum space, which is obtained by setting and in Eq. 1.

The above considerations are true for idealized systems which can be studied in the thermal limit. In fact, heavy-ion collisions will never be such an ideal system for a number of reasons NA49SFM . To reveal the predicted power-law exponents, it is necessary to consider a large number of background effects. Such effects include the finite lifetime of the system, global and local conservation laws, finite experimental acceptance, freeze out dynamics, resonance decays as well as other possible sources for correlations. In other words it is important to understand the non-critical background. This can only be done within well understood transport simulations.

In this study we will employ the UrQMD transport model ppnp41255 ; JPG251859 with (mean-field mode, UrQMD/M) and without the hadronic potentials (cascade mode, UrQMD/C) to generate a large number of events for nuclear collisions at different bombarding energies. From these events the second order SFMs will be calculated. Similar to what was done in Ref.NA49SFM , a correlation-free background can be generated from mixed events, where particles are taken from different events randomly. Any critical behavior is expected to be encoded in the approximate correlator, which can be estimated by the difference between the SSFMs of the real events and the associated mixed events :

| (3) |

The power law scaling of the correlator can be extracted by a fit to the dependence of the critical component () for NA49SFM , which will then be investigated and compared to the expected critical exponents.

Using the mean-field mode of the UrQMD model plb659525 ; plb623395 ; JPG36015111 ; mpla27 ; scpma59632001 ; mplalpc , density-dependent potentials for both formed hadron and pre-formed hadron from string fragmentation are treated in a similar way. The density dependent potential reads

| (4) |

where , and are parameters. In this work, a soft equation of state is adopted with -110.49 MeV, =182.014 MeV, = 1.17. Here, fm-3 is the nuclear matter saturation density, and is the hadronic density, which has contributions from formed and pre-formed baryons with , and from pre-formed mesons with a reduction factor based on the light-quark counting rules.

The momentum-dependent term of the hadronic potentials reads as:

| (5) |

where and are parameters. A detailed description on how the model parameters be fixed can be found in Ref. prc72064908 . For simplicity, the momentum-dependent term is only considered for formed baryons, and a two-body Coulomb potential is included for formed charged particles only.

Furthermore, relativistic effects on the relative distance and relative momentum between two particles and are taken into account:

| (6) | |||||

| (7) |

where the velocity factor ) and the . Additionally, , a covariance-related reduction factor for potentials in the Hamiltonian used as in the simplified version of the relativistic quantum molecular dynamics (RQMD/S) model prc101034915 ; prc72064908 ; PTP96263 ; EPJA5418 ; prc97064913 .

III results

In the following we will show the results of the proton intermittency analysis for 40Ar+45Sc, 131Xe+139La collisions with centralities 0-5%, 5-10% and 10-15% and central 197Au+197Au collisions (0-10%) (the centrality is defined by impact parameter distribution of the UrQMD model). The analysis is done for protons (and neutrons) with transverse momenta of GeV/, in the mid-rapidity region, i.e. with rapidity . To accumulate enough statistics for the analysis, more than 600K events are simulated for each scenario.

Fig.1 shows the resulting second scaled factorial moment and the estimator of the correlator for 5-10% central 40Ar+45Sc collisions at 40 GeV calculated within UrQMD model with and without hadronic potentials. In panel (a), the intermittency effect, i.e. the difference in between real events and mixed events, shows up for . Therefore, to determine the intermittency index, a fit of using Eq. 2 was used for . The resulting curve is shown in panel (b) of Fig.1. For the UrQMD cascade mode, the results for the moments of the real and mixed events are almost identical, and the values of fluctuate around zero, implying no effect. In the mean-field mode, the of real events rises significantly above those of mixed events, the extracted intermittency index is . This value of is similar to the one found in the NA61 preliminary analysis NA61 .

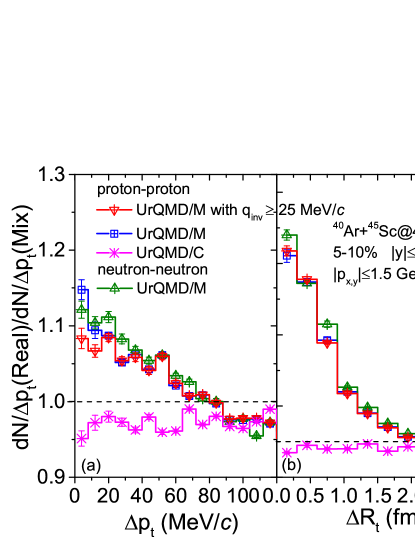

To understand what causes the non-vanishing intermittency index in the model simulation, we further investigate the baryon pair correlations in momentum and coordinate space. Fig.2 shows the distribution of and , over the mixed background, for proton and neutron pairs, in the same simulations. Here, the relative transverse momentum and the relative radial distance are defined as:

| (8) | |||||

| (9) |

In Fig.2, the baseline scenario of the cascade simulation (magenta line with cross symbols) does not show any structure in the relative transverse momentum and coordinate difference distributions as compared to the mixed background. Since in the cascade mode, the hadrons interact with each only through binary scattering according to a geometrical interpretation of elastic and inelastic cross sections. The ratio real/mixed is only slightly below unit due to conservation law effects. On the other hand, the and distributions in the simulation with potentials show a clear increase for small relative transverse momentum MeV/ and fm. To further interpret the observed increase in the and distributions, we found that with the consideration of the hadronic potentials, the real collision case has 0.029 proton pairs per event more than that of mixed collisions case at 64 MeV/. This is true for both, proton (blue line with squares) and neutron pairs (olive line with up triangles), indicating that the Coulomb interaction is less important for this distribution, and the effect of the Coulomb interaction of formed charged particles on this distribution is weaker than that of hadronic potentials. In addition, applying a cut (red line with down triangles), similar to that of the NA61 analysis NA49SFM in the relative invariant four-momentum 25 MeV/ only has a small effect on the distributions (20 MeV/).

Furthermore, to estimate the effect of the coalescence afterburner on these distributions we employ a minimum spanning tree (MST) algorithm for phase space coalescence. Fig.3 shows the and distributions of proton pairs from UrQMD/M mode with (UrQMD/M+MST) and without (UrQMD/M, blue lines) the coalescence afterburner. The phase-space coalescence afterburner (MST) used the parameter set of (, )=(2.8 fm, 0.25 GeV/ and 3.8 fm, 0.3 GeV/), indicated by red lines and olive lines respectively, for the relative momenta and distances scpma2016 ) in the final freeze-out stage as conditions for cluster formation. In the MST algorithm, nonphysical clusters (such as di-neutrons or di-protons) are eliminated by breaking them into free nucleons. The available data of deuteron and Helium-3 productions can be described fairly well by the UrQMD model with the above empirical coalescence parametersscpma2016 ; Sombun:2018yqh . By adjusting the parameter of MST, one can found that the coalescence afterburner has no effect on the proton-proton correlations. This means that the observed correlations in the low and can be readily understood as result of the attractive potentials between the nucleons. This attractive interaction eventually also is the reason for nuclear fragment formation, e.g. for the formation of bound pronto-neutron systems, the deuteron.

III.1 Centrality dependence

Next we study the centrality dependence of intermittent fluctuations in the transverse plane. Fig.4 depicts the centrality dependence of the second-order intermittency index in 40Ar+45Sc collisions. Panels (a), (b) and (c) are for 0-5%, 5-10% and 10-15% collisions, respectively. The calculated results from UrQMD/C (open squares) and UrQMD/M (solid squares) are shown together with the experimental data from NA61/SHINE (stars) with different proton purities NA61 for comparison. In experiment, the profile of SSFMs is affected by the proton purity selection, thus a full scan in proton purity, at thresholds of 80%, 85%, and 90% are shown. The black dash line presents the expected for a second-order phase transition calculated based on the effective action belonging to 3D Ising model Antoniou2006 . The intermittency index calculated by the UrQMD/C model is essentially zero. Further, with the inclusion of hadronic potentials, it is found that the intermittency index is increased and comparable to the NA61/SHINE data in different centrality bins. In addition, it can be seen that slightly increases with increasing impact parameter, which is also consistent with the findings in the experiment Davisapb . This result is due to the decreasing size of the system which goes along with a shortened hadronic freeze out phase npa20201003 ; prc73044905 ; prc90054907 .

III.2 Energy and system dependence of

Finally, an energy scan of the intermittency in collisions of 40Ar+45Sc, 131Xe+139La and 197Au+197Au is presented. Fig.5 summaries the calculated energy excitation function of the second-order intermittency index. Panels (a), (b) and (c), respectively, are for 40Ar+45Sc at 0-5%, 5-10% and 10-15%. And panels (d), (e) and (f) are for 131Xe+139La collisions. We observe that the calculated with the UrQMD/C data (open squares) is essentially zero no matter the centrality or energy, and no intermittency effect is observed. In the mean-field mode, the second-order intermittency index (solid squares) is slightly increasing with the energy and/or centrality.

Fig.6 shows the excitation function of from the UrQMD model for 0-10% central Au+Au collisions at several different energies. Here, we present results for Au+Au systems as they are studied in the beam energy scan of the STAR experiment. Again, we observe an increase of the intermittency index as function of beam energy. The UrQMD results in Fig.6 are also compared to conjectured values of which are based on a theoretical interpretation of STAR data plb801135186 ; arxiv2002 . The data (red stars) from Ref. plb801135186 are obtained by a mapping of the ratio on the neutron number fluctuations in most central (0-10%) Au + Au collisions arxiv2002 . These indirectly reconstructed fluctuations are then again mapped onto the obtained relation between the relative density fluctuation of baryons n and . The shadowed band corresponds to the systematic errors from the experimental data. Even though the magnitude and energy dependence of the indirectly calculated data is similar to the model results plb801135186 one should be cautious with this comparison due to the indirect nature of how is extracted. A future direct measurement would allow a much more direct comparison with data.

IV summary

Investigations on the second order scaled factorial moments of proton number fluctuations in transverse momentum space of HICs, within the UrQMD transport model, have been presented. It was found that the inclusion of hadronic mean-field potentials introduce a non-zero intermittency index which is consistent with the reported data of the NA49/NA61 experiment.

The energy dependence (, , GeV), system size (+45Sc, 131Xe+139La, 197Au+197Au) and centrality (0-5%, 5-10%, 10-15%) dependence is studied in the UrQMD model with and without hadronic potentials. A clear dependence of beam energy and centrality is observed. In the present study the increase of the SFMs is due to an enhancement of proton pairs (approximately 0.029 pairs per event for the case of 5-10% central Ar+Sc collisions at 40 GeV) with small relative momenta MeV/ due to attractive nuclear forces. With a further consideration of the traditional coalescence afterburner, the observed correlations of protons were found to not be influenced by the coalescence parameters. More theoretical and experimental studies on the effect of both, hadronic interactions, the stiffness of the equation of state, and the final-state interactions are required to shed light on the intermittency in heavy ion collisions, especially for lower collision energies.

Acknowledgements.

The authors acknowledge support by the computing server C3S2 in Huzhou University. The work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11875125, U2032145, and 12047568), the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant No. 2020YFE0202002, and the “Ten Thousand Talent Program” of Zhejiang province. JS thanks the Samson AG and the BMBF through the ErUM-data project for funding.References

- (1) J. C. Collins, M. J. Perry, Phys. Rev. Lett. 34 (1975) 1353.

- (2) N. Cabibbo, G. Parisi, Phys. Lett. B 59 (1975) 67.

- (3) E. V. Shuryak, Phys. Lett. B 78 (1978) 150.

- (4) H. Fritzsch, M. Gell-Mann, H. Leutwyler, Phys. Lett. B 47 (1973) 365.

- (5) C. Bernard, T. Burch, C. DeTar, et al., Phys. Rev. D 71 (2005) 034504.

- (6) Y. Aoki, G. Endrodi, Z. Fodor, et al., Nature 443 (2006) 675.

- (7) A. Bazavov, et al., (HotQCD Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 90 (2014) 094503.

- (8) P. Braun-Munzinger, V. Koch, T. Schäfer, J. Stachel, Phys. Rep. 621 (2016) 76.

- (9) M. A. Stephanov, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 20 (2005) 4387.

- (10) K. Fukushima, C. Sasaki, Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 72 (2013) 99.

- (11) G. Baym, T. Hatsuda, T. Kojo, et al., Rep. Progr. Phys. 81 (2018) 056902.

-

(12)

STAR Collaboration, STAR Note 598, STAR white paper, “Studying the Phase Diagram of QCD Matter at RHIC”, 2014,

https://drupal.star.bnl.gov/STAR/starnotes/public/sn0598. - (13) NA61/SHINE Collaboration, CERN-SPSC-2009-001; SPSC-P-330-ADD-4, “Proposal for secondary ion beams and update of data taking schedule for 2009-2013”.

- (14) A. Andronic, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 29 (2014) 1430047.

- (15) S. Jeon, V. Koch, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83 (1999) 5435.

- (16) M. Asakawa, U. Heinz, B. Müller, Phys. Rev. Lett. 85 (2000) 2072.

- (17) V. Koch, A. Majumder, J. Randrup, Phys. Rev. Lett. 95 (2005) 182301.

- (18) S. Ejiri, F. Karsch, K. Redlich, Phys. Lett. B 633 (2006) 275.

- (19) M. A. Stephanov, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102 (2009) 032301.

- (20) X. H. Jin, J. H. Chen, Z. W. Lin, , Sci. Sin. Phys. Mech. Astron. 62 (2019) 011012.

- (21) X. F. Luo, Nu Xu, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28 (2017) 112.

- (22) A. Bazavov, et al., (HotQCD Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 96 (2017) 074510.

- (23) A. Bazavov, et al., (HotQCD Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 101 (2020) 074502.

- (24) Y. Ye, Y. Wang, Q. Li, et al., Phys. Rev. C 101 (2020) 034915.

- (25) A. Bzdak, S. Esumi, V. Koch, et al., Phys. Rep. 853 (2020) 1.

- (26) J. Adam, et al., (STAR Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 126 (2021) 092301.

- (27) T. Anticic, B. Baatar, J. Bartke, et al., Eur. Phys. J. C 75 (2015) 587.

- (28) N. G. Antoniou, Y. F. Contoyiannis, F. K. Diakonos, et al., Nucl. Phys. A 693 (2001) 799.

- (29) A. Bialas and R. Peschanski, Nucl. Phys. B 273 (1986) 703.

- (30) A. Bialas and R. Peschanski, Nucl. Phys. B 308 (1988) 857.

- (31) N. G. Antoniou, Y. F. Contoyiannis, F. K. Diakonos, et al., Nucl. Phys. A 761 (2005) 149.

- (32) N. G. Antoniou, F. K. Diakonos, A. S. Kapoyannis, et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, (2006) 032002.

- (33) T. Anticic, et al., (NA49 Collaboration), Phys. Rev. C 81 (2010) 064907.

- (34) N. Davis, (for the NA61/SHINE Collaboration), Acta Phys. Pol. B Proc. Suppl. 13 (2020) 637.

- (35) N. Davis, et al., (for the NA61/SHINE Collaboration), in Proceedings of the CPOD 2018, Corfu Island, Greece, 24-28 September 2018.

- (36) N. Davis, et al., (for the NA61/SHINE Collaboration), Acta Phys. Polon. B 50, 1029 (2019).

- (37) J. Wu, Y. Lin, Y. Wu, Z. Li, Phys. Lett. B 801 (2020) 135186.

- (38) P. Mali, A. Mukhopadhyay, G. Singh , Acta Phys. Pol. B 43 (2012) 463.

- (39) Tamás Vicsek, Fractal growth phenomena, World Scientific, Singapore N. Jersey (1989), ISBN: 9971-50-830-3.

- (40) N. G. Antoniou and F. K. Diakonos, J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 46 (2019) 035101.

- (41) S. A. Bass, M. Belkacem, M. Bleicher, et al., Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 41 (1998) 255.

- (42) M. Bleicher, E. Zabrodin, C. Spieles, et al., J. Phys. G 25 (1999) 1859.

- (43) Q. Li, M. Bleicher, and H. Stöcker, Phys. Lett. B 659 (2008) 525.

- (44) Q. Li, M. Bleicher, and H. Stöcker, Phys. Lett. B 663 (2008) 395.

- (45) Q. Li, M. Bleicher, J. Phys. G 36 (2009) 015111.

- (46) Q. Li, Z. Li, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 27 (2012) 1250004.

- (47) Q. Li, Y. Wang, X. Wang , Sci. Sin. Phys. Mech. Astron. 59 (2016) 632001.

- (48) P. Li, Y. Wang, J. Steinheimer , Mod. Phys. Lett. A 35 (2020) 2050289.

- (49) T. Maruyama, K. Niita, T. Maruyama, et al., Prog. Theor. Phys. 96 (1996) 263.

- (50) M. Isse, A. Ohnishi, N. Otuka, et al., Phys. Rev. C 72 (2005) 064908.

- (51) Y. Nara, H. Niemi, A. Ohnishi, et al., Eur. Phys. J. A 54 (2018) 18.

- (52) C. Zhang, J. Chen, X. Luo, et al., Phys. Rev. C 97 (2018) 064913.

- (53) Q. F. Li, Y. J. Wang, X. B. Wang, et al., Sci. China-Phys. Mech. Astron. 59 (2016) 622001;59 (2016) 632002;59 (2016) 672013 (2016).

- (54) S. Sombun, K. Tomuang, A. Limphirat, et al., Phys. Rev. C 99 (2019) 014901.

- (55) N. G. Antoniou, N.Davis, F.K.Diakonos, et al., Nucl. Phys. A 1003 (2020) 122018.

- (56) F. Becattini, J. Manninen, M. Gazdzicki, Phys. Rev. C 73 (2006) 044905 (2006).

- (57) F. Becattini, M. Bleicher, E. Grossi, et al., Phys. Rev. C 90 (2014) 054907.

- (58) D. W. Zhang, (for the STAR Collaboration), Nucl. Phys. A 1005 (2021) 121825.