∎

22email: [email protected]

PGA-based Predictor-Corrector Algorithms for Monotone Generalized Variational Inequality

Abstract

In this paper, we consider the monotone generalized variational inequality (MGVI) where the monotone operator is Lipschitz continuous. Inspired by the extragradient method MR451121 and the projection contraction algorithms MR1418264 ; MR1297058 for monotone variational inequality (MVI), we propose a class of PGA-based Predictor-Corrector algorithms for MGVI. A significant characteristic of our algorithms for separable multi-blocks convex optimization problems is that they can be well adapted for parallel computation. Numerical simulations about different models for sparsity recovery show the wide applicability and effectiveness of our proposed methods.

Keywords:

Monotone Generalized variational inequality Lipschitz continuous PGA-based Predictor-Corrector algorithms parallel computation1 Introduction

Let be a closed proper convex function, and a vector-valued and continuous mapping. The generalized variational inequality (GVI) MR686212 ; MR1673631 takes the next form

Here, we keep the arithmetic operation that . In this paper, we focus on the case where is monotone, i.e., for all . In this case, the corresponding GVI is called monotone generalized variational inequality (MGVI). Throughout this paper, we make the following additional assumptions for :

Assumption 1

-

(a)

The monotone operator is Lipschitz continuous with Lipschitz constant .

-

(b)

The solution set of , denoted as , is nonempty.

Various convex optimization problems can be formulated as MGVIs, such as lasso problem, basis pursuit problem MR1854649 , basis pursuit denoising problem MR2481111 , and Dantzig selector MR2382651 , to name a few. Moreover, MGVI contains the classical monotone variational inequality (MVI). One sees this by setting 111 is the indicator function of which is equal to if and otherwise. with being a nonempty closed convex set, then MGVI reduces to MVI in form of

For solving , the extragradient method MR451121 can be applied. Specifically, at iteration , in predictor step, the projection operator is used for generating a predictor where is selected to satisfy some given condition, then in corrector step, . This method yields a sequence converging to a solution of . On the other hand, He MR1418264 ; MR1297058 proposed a class of projection and contraction methods for , which also belongs to a class of Predictor-Corrector algorithms. In predictor step, the predictor is the same with the above extragradient method as , then the corrector step is based on the next three fundamental inequalities for constructing different profitable directions:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where is any solution of , and . Numerical simulations therein MR1418264 ; MR1297058 show that the methods proposed by He outperformed the extragradient method in general.

Inspired by both of their works for , we generalize their ideas for . Firstly, for generalizing the idea of extragradient method for , at iteration and in predictor step, we use the proximity operator to yield a predictor , where is selected to meet some given condition, then in corrector step, we set as . The resulting algorithm can be deemed as a natural generalization of extragradient method (EM) for . Thus we denote our algorithm as GEM. The difference between GEM and EM is the different operator used in both predictor and corrector steps. Surprisingly, this kind of modification does not change the key inequality for the convergence analysis of GEM compared with that for EM. Secondly, for generalizing the idea of He’s projection and contraction algorithms, we also use the proximity operator to make a predictor , then we likewise obtain three fundamental inequalities as follows:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where is any solution of , and . We observe that the leftmost terms of (4) and (5) are opposite to each other, thus they can be eliminated when adding (4) and (5), or when adding (4), (5) and (6). This yields the same results with that when adding (1) and (2), or adding (1), (2), and (3). The latter is used by He in corrector step for constructing projection and contraction algorithms for . Thus, the methodologies developed by He for can be straightforwardly inherited. This is an inspiring result. The only difference between He’s works for and our proposed algorithms for will be the different predictors, which differ a little. Here, it should be mentioned that He et al. MR2902659 ; MR3049509 ; MR3128749 ; MR2500836 developed diverse PPA-based contraction methods for , one can also refer to MR3618786 for a review about the works of He et al. in and . Although their PPA-based contraction algorithms possess the contraction properties, the various corrector strategies developed by them for are not used. Thus our proposed algorithms for differ from theirs. Part of our contribution in this paper is to construct a direct link between their previous works in and later works in . The above two generalizations can be treated as Predictor-Corrector algorithms, and both of them use the proximity operator for making predictors, thus we call our algorithms as PGA-based Predictor-Corrector algorithms.

Note that in order to make our algorithms to be implementable in practice, the proximity operator of should be easy to compute. The reader can refer to MR3616647 ; MR3719240 ; MR2858838 for a wide variety of computable proximity operators. Finally, we mention that for the structured convex optimization problem with a separable objective function and linear constraint, our proposed algorithms can be well adapted for parallel computation, which can not be realized by many algorithms related to ADMM. This is a significant characteristic of our algorithms, allowing lesser time exhausted by employing the technique of parallel computation, especially in case of large-scale multi-blocks separable problems.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In section 2, we recall some notations and preliminaries. Then in section 3, we will introduce the first class of our proposed PGA-based Predictor-Corrector algorithms, which is a natural generalization of extragradient method. Next in section 4, the second class of our algorithms will be introduced. In section 5, we will discuss and compare our proposed algorithms with ADMM-related algorithms with respect to a concrete convex optimization problem. Finally in section 6, we test our proposed algorithms for different sparsity recovery models.

2 Notations and preliminaries

Let denote the -dimensional Euclidean space with standard inner product , i.e., for any , and denote the Euclidean norm. Given a function , the set

denotes its effective domain. If , then is called a proper function (or proper). The set

denotes the epigraph of , and is closed (resp. convex) if is closed (resp. convex). The function is called a closed proper convex function if it is proper, closed and convex.

Now, let be a closed proper convex function, the proximity operator of is defined as follows:

the optimal solution is unique. If with being a nonempty closed convex set, then the above proximity operator reduces to the usual projection operator .

Lemma 1 (MR3719240 )

Let be a closed proper convex function. Then the next three conditions are equivalent:

-

1.

.

-

2.

.

-

3.

For all , it holds that

For any , let . The next theorem shows that is a solution of if and only if .

Lemma 2

For any , is a solution of if and only if .

Proof

Thus, solving reduces to solving a zero point of . So, for given , can be treated as a error measure function. Next we will show that is a non-decreasing function about , while is a non-increasing function about . This show that can be used for stopping criterion when implementing algorithms. The next result can be seen by a simple modification of notations in the proof of Theorem 10.9 in MR3719240 .

Lemma 3 (MR3719240 )

For all , and , it holds that

| (7) |

and

| (8) |

Before ending this part, for simplifying the convergence analysis of our proposed algorithms, the definition of Fejér monotone sequence and its related properties are recalled.

Definition 1 (Fejér monotone sequence)

Let be nonempty, and let be a sequence in , then is Fejér monotone with respect to if for all and any , it holds that

Lemma 4 (MR3616647 )

Let be nonempty, and let be a Fejér monotone sequence with respect to , then the following hold

-

•

is bounded;

-

•

If any subsequence of converges to a point in , then converges to a point in .

3 Generalized Extragradient Method for

In this section, we will introduce the first class of our PGA-based Predictor-Corrector algorithms for solving . The motivation for our algorithm is the extragradient method (EM) MR451121 , which is designed for solving . Our algorithm for can be deemed as a natural generalization of EM, and is denoted by us as GEM. The difference of GEM from EM is that the proximity operator is used for both of the predictor and corrector steps, while projector operator is used in EM. Next, we will show firstly GEM for in Algorithm 1, followed by the its convergence.

Remark 1

In order to prove the convergence of GEM, we need the next propositions.

Proposition 1

Let , , and let

then the following inequality holds

Proof

Next, we prove the key inequality for the convergence analysis of GEM, which is based on proposition 1.

Proposition 2

Let be the sequence generated by GEM (Algorithm 1), and let be any solution of , then the next inequality holds

Proof

Substituting , , , , and in the inequality of proposition 1, we obtain

| (11) |

On the other hand, implies that

| (12) |

Adding inequality (12) to the right side of inequality (11), then it follows that

| (13) |

where the second equality follows from

Moreover, (Lemma 4) implies that

| (14) |

Then adding (14) to the right side of (13), it follows that

| (15) |

Considering also that

| (16) |

then combining (15) and (16), and also taking into account that

we conclude that

∎

Theorem 3.1 (Convergence of GEM for )

Let be the sequence generated by GEM, and let be bounded such that . Then converges to a solution of .

Proof

One sees from proposition 2 that for all , and any , it holds that

This implies that is Fejér monotone with respect to . Adding the above inequality from to , taking some rearrangements, and letting , then it holds that

Thus , this implies that , from which we conclude and have common limit points. Let be any of their common limit points, then and . Because is bounded and , without loss of generality, one can assume that with . Clearly, , then it follows from Lemma 1 that for any , it holds

thus

| (17) |

On the other hand, because is a closed proper convex function, this implies that is lower semicontinuous, thus . Thus

| (18) |

Then combining (3) and (18), and considering that , we conclude that

for any . Thus is a solution of , i.e., . Finally, because is Fejér monotone with respect to , is any limit point of , and , thus Lemma 4 implies that converges to a solution of . ∎

Remark 2

To guarantee the convergence of GEM (Algorithm 1), requires to be bounded with . One can select with . However, in some applications, can not be explicitly computed, or it is evaluated conservatively, the latter causes small which usually results in slow convergence. Thus, one can take some adaptive rules for choosing at each iteration.

4 Proximity and Contraction Algorithms for

In this section, we will introduce the second class of our PGA-based Predictor-Corrector algorithms for . We are inspired by the works of He for in MR1418264 ; MR1297058 , where the projection operator is used for making a predictor, while our algorithms for use proximity operator for making a predictor. The corrector strategies developed by He for can be inherited in our algorithms, this is an inspiring result. Considering that the algorithms developed by He for are called as projection and contraction algorithms, our algorithms depend on the strategies for corrector steps by He, and our algorithms also enjoy the contraction properties, thus we name our algorithms as proximity and contraction algorithms. In the sequel, we will just employ part of the corrector strategies developed by He for constructing our algorithms, the reader can refer to MR1418264 ; MR1297058 for more strategies for corrector step.

Firstly, we introduce three fundamental inequalities, which are key for constructing our algorithms for .

Proposition 3 (Three fundamental inequalities)

Let be any solution of , and for any and , let , then the following three inequalities hold:

| (FI1) |

| (FI2) |

| (FI3) |

Proof

We observe that the leftmost terms of (FI1) and (FI2) are opposite to each other, so they can be eliminated when adding (FI1) and (FI2), or when adding (FI1), (FI2) and (FI3). This observance makes it possible for us to directly employ the strategies of corrector step developed by He in MR1418264 ; MR1297058 for .

4.1 Proximity and contraction algorithms based on (FI1) and (FI2)

In this part, we consider with . Then (FI1) and (FI2) take the next forms

and

Adding the above two inequalities together, one obtains that

| (19) |

where the last inequality holds because is positive semi-definite222Here, is not required to be symmetric., i.e., for all , . Replacing the above , , by , , respectively, and setting

then it follows that . Next, we use

to obtain the next surrogate, then one sees

Note that obtains its maximum at , thus by setting , one sees that

| (20) |

Note that . Thus, implies that .

The aforementioned algorithm, denoted as , is summarized in Algorithm 2.

Next, we construct another proximity and contraction algorithm, which is based on that is symmetric positive semi-definite. In this case, setting , , and let , , then one sees . Let , one sees that

Note that obtains its maximum at , thus by setting , one sees that

Note that .

The above method for symmetric , denoted as , is summarized below in Algorithm 3.

Theorem 4.1 (Convergence of and for )

Let and be the sequences generated by and , respectively, and for , let be bounded with . Then (resp. converges to a solution of the corresponding .

Proof

We will just prove the convergence of since the proof of the convergence of follows the similar argument.

Let be any solution of . The inequality (4.1) implies that is Fejér monotone with respect to , moreover, by adding from to , taking some rearrangements, and letting , then it holds that

Because , thus the above inequality implies , for which we conclude that and have common limit points. Then the similar argument in Theorem 3.1 implies that converges to a solution of . ∎

Remark 3

To guarantee that (Algorithm 2) converges, requires to be bounded such that . The adaptive rule

was suggested by He for , and can also be applied to our algorithms. For , , the convergence is guaranteed with being any positive constant, one possibility may be .

4.2 Proximity and contraction algorithms based on (FI2), (FI2) and (FI3)

In this part, we consider the case where is monotone. By adding (FI1), (FI2) and (FI3) together, one obtains that

thus it holds that

| (21) |

Replacing the above , , by , , respectively, and setting

then one sees that . For a fixed , considering that is lipschitz continuous with parameter , thus some can be selected such that

thus . By setting , one sees that

Note that obtains its maximum at , and one also sees that

thus for all . Setting , then one obtains that

The aforementioned algorithm, denoted as , is summarized in Algorithm 4.

Finally, we distinguish a special case where with being a symmetric positive semi-definite matrix, and being a constant vector. In this case, inequality (21) takes the next form

Setting with being a fixed positive constant smaller than , thus is a symmetric positive definite matrix. Replacing the above and by and , respectively. Then, one sees that

Let , thus it follows that

The above method for symmetric is denoted as , the corrector strategy was not mentioned by He, but it can be simply constructed from (21), we summarize it below in Algorithm 5.

The convergence analysis of and can be proved with essentially the argument that was used in Theorem 4.1.

Theorem 4.2 (Convergence of and for )

Let and be the sequences generated by and , respectively, and for , let be bounded with . Then (resp. converges to a solution of the corresponding .

Remark 4

In the description of , , and , we neglect the fact that may be equal to , however, this will hardly happen in practice, moreover, when implementing these algorithms, one may priorly determine whether .

5 A Discussion about Our Algorithms

In the preceding sections, we introduce our algorithms for , while in this part, we will show the characteristics of our algorithms with respect to the following separable two-blocks convex optimization model.

| (22) |

where , , , and are two closed proper convex functions.

The well known alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) MR724072 is very popular for problem (22), the reader can refer to BoydADMM and references therein for efficient applications of ADMM in a variety of fields. The procedure of ADMM is shown below in Algorithm 6.

-

(a)

;

-

(b)

;

-

(c)

.

Note that the computation of and in the general step of ADMM may be much more complex than the computation of the proximity operators of and , thus some variants of ADMM have been proposed for dealing with such matters. One of them is the alternating direction proximal method of multipliers (AD-PMM) MR3719240 , and a special case of AD-PMM is the the alternating direction linearized proximal method of multipliers (AD-LPMM), which just requires the computation of the proximity operators of and . AD-LPMM for problem (22) is show in Algorithm 7.

-

(a)

;

-

(b)

;

-

(c)

.

Next, we will introduce our algorithms for problem (22). Consider the lagrangian function of problem (22)

Then is a saddle point of problem (22) if and only if

the latter is equivalent to

for all . This fits with

For the theory of saddle point, one can see e.g., MR2184037 . Now we only need to keep in mind that if is a saddle point of problem (22), then will be a minimizer of problem (22).

Note that our algorithms and are designed for some specified operators about , which can not be applied for this problem. Moreover, for problem (22), owing to the special form of , this causes that the resulting and will only differ in the computation of when the same self-adaptive rule is employed. For these reasons, we will firstly show GEM and in Algorithm 8 and 9, respectively. A self-adaptive rule for is also included into these two algorithms. The computation of in for problem (22) is given in Algorithm 10.

In the preceding part of this section, we have introduced five algorithms for problem (22). Now, let us take a close look at them. Firstly, ADMM (Algorithm 6) may not be implementable in practice because compared with the computation of proximity operators of and , it may be much harder to solve the next two convex optimization problems

Next, let us look at AD-LPMM (Algorithm 7) and the other three algorithms proposed by us. Firstly, at iteration , AD-LPMM solves in order, while the other three algorithms solve and in parallel, this is a significant characteristic of our algorithms, allowing lesser time exhausted by employing the technique of parallel computation, especially in case of large-scale multi-blocks separable problems. Secondly, although the proximity operators of and are used by all of the four algorithms, more computation is involved by AD-LPMM in updating and because it requires to compute and , while our algorithms only require the computation of or . Finally, AD-LPMM additionally evaluates in advance the maximal eigenvalues of and , which is not necessary for our algorithms. Now, let us look at our proposed algorithms , , and GEM. The predictor steps are the same for all of them, who use the proximity operators of and for making the predictors. In corrector step, GEM employs again the proximity operators for obtaining the next surrograte , while for the other two algorithms, only some cheap matrix-vector products, additions, and so on are involved. Thus, when the computation of proximity operators of and requires some iterative techniques, the corrector step of GEM will be more complex than that of and . Finally, we point out that the value of in is lesser or equal to its counterpart in .

6 Numerical Simulations

In this section, we report some numerical results of our proposed algorithms. Our algorithms are implemented in MATLAB. The experiments are performed on a laptop equipped with Intel i-U GHz CPU and GB RAM.

6.1 First Example

Consider the next -regularized least square problem

| (23) |

where , , and . This problem fits with

We generate an instance of the problem with and for showing the iterative shrinkage-thresholding algorithm (ISTA) and our proposed algorithms GME, , , , . The components of are independently generated by using the standard normal distribution, the ”true” vector x_true is a sparse vector with 20 non-zeros elements, which is generated by the following matlab command:

then we set . The initial point for all of the algorithms are , the vector of all ones. The stopping criterion for all of them is

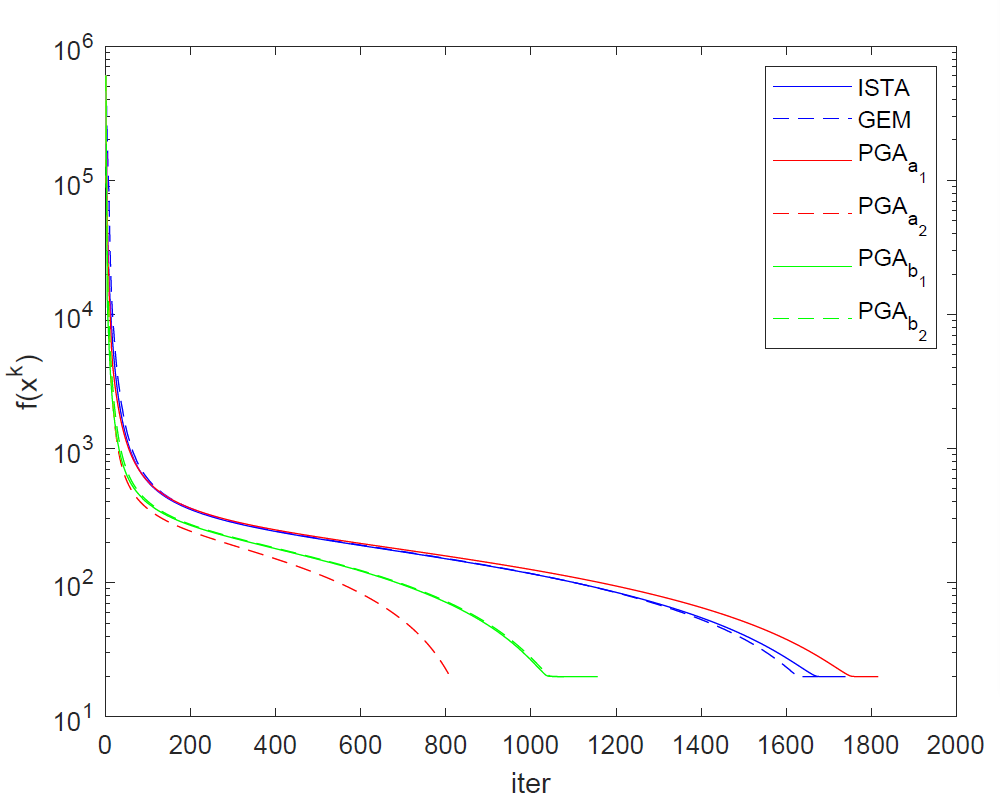

The trends about the values of of ISTA, GME, , , , on -regularized least squares problem are shown in Fig. 1. The number of iteration and CPU time for all of thm is shown in Table 1. All of them recover the ”true” vector.

| No. of iteration | CPU time (seconds) | |

|---|---|---|

| ISTA | 1739 | 5.36 |

| GEM | 1682 | 11.10 |

| 1816 | 24.93 | |

| 822 | 4.20 | |

| 1157 | 7.31 | |

| 1085 | 3.38 |

6.2 Second Example

Consider the next basis pursuit problem

| (24) |

where , . This problem matches with , and We use the same data as in the preceding example for showing AD-LPMM , and our algorithms GME, , . The initial point for all the algorithms are , the vector of all ones, and , the vector of all zeros. The stopping criterion for all the algorithms except AD-LPMM are , while that for AD-LPMM is . Results of AD-LPMM, , , GEM on basis pursuit problem are shown in Table 2, where we show the number of iteration and CPU time for all of them. All of these algorithms recover the ”true” vector.

| No. of iteration | CPU time (seconds) | |

|---|---|---|

| AD-LPMM | 1773 | 18.65 |

| GEM | 105 | 4.65 |

| 225 | 7.58 | |

| 226 | 7.05 |

7 Conclusion

In this paper, we propose some PGA-based Predictor-Corrector algorithms for solving . Our works are inspired by the extragradient method and the projection and contraction algorithms for . The form of our algorithms is also simple, and one of their significant characteristic for separable multi-blocks convex optimization problems is that they can be well adapted for parallel computation, allowing our algorithms can be well applied in large-scale settings. Preliminary simulations of our algorithms in the sparsity recovery models show their effectiveness when compared with some existing algorithms.

Acknowledgements.

My special thanks should go to my friend, Kuan Lu, who has put considerable time and effort into his comments on the draft.References

- (1) Bauschke, H.H., Combettes, P.L.: Convex analysis and monotone operator theory in Hilbert spaces, second edn. CMS Books in Mathematics/Ouvrages de Mathématiques de la SMC. Springer, Cham (2017). DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-48311-5. URL https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48311-5. With a foreword by Hédy Attouch

- (2) Beck, A.: First-order methods in optimization, MOS-SIAM Series on Optimization, vol. 25. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM), Philadelphia, PA; Mathematical Optimization Society, Philadelphia, PA (2017). DOI 10.1137/1.9781611974997.ch1. URL https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611974997.ch1

- (3) Bertsekas, D.P.: Convex analysis and optimization. Athena Scientific, Belmont, MA (2003). With Angelia Nedić and Asuman E. Ozdaglar

- (4) Boyd, S., Parikh, N., Chu, E., Borja, P., Jonathan, E.: Distributed optimization and statistical learning via the alternating direction method of multipliers. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning 3(1), 1–122 (2011)

- (5) Bruckstein, A.M., Donoho, D.L., Elad, M.: From sparse solutions of systems of equations to sparse modeling of signals and images. SIAM Rev. 51(1), 34–81 (2009). DOI 10.1137/060657704. URL https://doi.org/10.1137/060657704

- (6) Candès, E., Tao, T.: Rejoinder: “The Dantzig selector: statistical estimation when is much larger than ” [Ann. Statist. 35 (2007), no. 6, 2313–2351; mr2382644]. Ann. Statist. 35(6), 2392–2404 (2007). DOI 10.1214/009053607000000532. URL https://doi.org/10.1214/009053607000000532

- (7) Chen, S.S., Donoho, D.L., Saunders, M.A.: Atomic decomposition by basis pursuit. SIAM Rev. 43(1), 129–159 (2001). DOI 10.1137/S003614450037906X. URL https://doi.org/10.1137/S003614450037906X. Reprinted from SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 20 (1998), no. 1, 33–61 (electronic) [ MR1639094 (99h:94013)]

- (8) Combettes, P.L., Pesquet, J.C.: Proximal splitting methods in signal processing. In: Fixed-point algorithms for inverse problems in science and engineering, Springer Optim. Appl., vol. 49, pp. 185–212. Springer, New York (2011). DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-9569-8˙10. URL https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9569-8_10

- (9) Fang, S.C., Peterson, E.L.: Generalized variational inequalities. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 38(3), 363–383 (1982). DOI 10.1007/BF00935344. URL https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00935344

- (10) Fortin, M., Glowinski, R.: Augmented Lagrangian methods, Studies in Mathematics and its Applications, vol. 15. North-Holland Publishing Co., Amsterdam (1983). Applications to the numerical solution of boundary value problems, Translated from the French by B. Hunt and D. C. Spicer

- (11) He, B.: A class of projection and contraction methods for monotone variational inequalities. Appl. Math. Optim. 35(1), 69–76 (1997). DOI 10.1007/s002459900037. URL https://doi.org/10.1007/s002459900037

- (12) He, B., Yuan, X.: Convergence analysis of primal-dual algorithms for a saddle-point problem: from contraction perspective. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 5(1), 119–149 (2012). DOI 10.1137/100814494. URL https://doi.org/10.1137/100814494

- (13) He, B., Yuan, X.: Linearized alternating direction method of multipliers with Gaussian back substitution for separable convex programming. Numer. Algebra Control Optim. 3(2), 247–260 (2013). DOI 10.3934/naco.2013.3.247. URL https://doi.org/10.3934/naco.2013.3.247

- (14) He, B., Yuan, X., Zhang, W.: A customized proximal point algorithm for convex minimization with linear constraints. Comput. Optim. Appl. 56(3), 559–572 (2013). DOI 10.1007/s10589-013-9564-5. URL https://doi.org/10.1007/s10589-013-9564-5

- (15) He, B.S.: A new method for a class of linear variational inequalities. Math. Programming 66(2, Ser. A), 137–144 (1994). DOI 10.1007/BF01581141. URL https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01581141

- (16) He, B.S.: From the projection and contraction methods for variational inequalities to the splitting contraction methods for convex optimization. Numer. Math. J. Chinese Univ. 38(1), 74–96 (2016)

- (17) He, B.S., Fu, X.L., Jiang, Z.K.: Proximal-point algorithm using a linear proximal term. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 141(2), 299–319 (2009). DOI 10.1007/s10957-008-9493-0. URL https://doi.org/10.1007/s10957-008-9493-0

- (18) Korpelevič, G.M.: An extragradient method for finding saddle points and for other problems. Èkonom. i Mat. Metody 12(4), 747–756 (1976)

- (19) Patriksson, M.: Nonlinear programming and variational inequality problems, Applied Optimization, vol. 23. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht (1999). DOI 10.1007/978-1-4757-2991-7. URL https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2991-7. A unified approach