Optical Observations of the Nearby Type Ia Supernova 2021hpr

Abstract

We present the optical photometric and spectroscopic observations of the nearby Type Ia supernova (SN) 2021hpr. The observations covered the phase of 14.37 to +63.68 days relative to its maximum luminosity in the band. The evolution of multiband light/color curves of SN 2021hpr is similar to that of normal Type Ia supernovae (SNe Ia) with the exception of some phases, especially a plateau phase that appeared in the color curve before peak luminosity, which resembles that of SN 2017cbv. The first spectrum we observed at t 14.4 days shows a higher velocity for the Si ii 6355 feature ( 21,000 km s-1) than that of other normal Velocity (NV) SNe Ia at the same phase. Based on the Si ii 6355 velocity of 12,420 km s-1 around the maximum light, we deduce that SN 2021hpr is a transitional object between high velocity (HV) and NV SNe Ia. Meanwhile, the Si ii 6355 feature shows a high velocity gradient (HVG) of about 800 km s-1 day-1 from roughly to days relative to the -band maximum, which indicates that SN 2021hpr can also be classified as an HVG SN Ia. Despite SN 2021hpr having a higher velocity for the Si ii 6355 and Ca ii near-IR (NIR) triplet features in its spectra, its evolution is similar to that of SN 2011fe. Including SN 2021hpr, there have been six supernovae observed in the host galaxy NGC 3147, and the supernovae explosion rate in the last 50 yr is slightly higher for SNe Ia, while lower for SNe Ibc and SNe II it is lower than expected rate from the radio data. Inspecting the spectra, we find that SN 2021hpr has a metal-rich (12 + log(O/H) 8.648) circumstellar environment, where HV SNe tend to reside. Based on the decline rate of SN 2021hpr in the band, we determine the distance modulus of the host galaxy NGC 3147 using the Phillips relation to be 33.46 0.21 mag, which is close to that found by previous works.

1 Introduction

Supernovae, among of the most violent astrophysical phenomena in the universe, are the endpoint of the evolution of some stars, meaning that those stars completely collapse. Type Ia supernovae (SNe Ia) have been used as good distance indicators to measure the accelerating expansion of the universe because of their high luminosities and homogeneous properties (Riess et al., 1998; Perlmutter et al., 1999; Riess et al., 2016, 2018). Presently, SNe Ia are widely used as ”standard candles” to measure the distances of external galaxies and are a means to determine the Hubble Constant (Riess et al., 1996; Guy et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2017; Burns et al., 2018; Freedman et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2020). Besides, SNe Ia are also produce most of the iron group elements in the universe and drive the evolution of the element abundances in galaxies (Dwek, 1998; Kobayashi et al., 1998; Kobayashi & Nomoto, 2009; Côté et al., 2016; Lacchin et al., 2021).

Two popular scenarios have been proposed for the progenitor of SNe Ia (Maoz et al., 2014): one is the single degenerate (SD) scenario (Whelan & Iben, 1973), in which a C/O white dwarf (WD) explodes when it reaches the Chandrasekhar mass limit by accreting material from its nondegenerate companion star. The other is double degenerate (DD) scenario (Webbink, 1984; Iben & Tutukov, 1984), in which the explosion is triggered by the merging of a double degenerate system via accretion or violent collision. Both SD (Sternberg et al., 2011; Dilday et al., 2012; Silverman et al., 2013; Maguire et al., 2013; Lundqvist et al., 2015; Bochenek et al., 2018) and DD (Li et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2015; Olling et al., 2015) scenarios are supported by multiple observational samples. However, the explosion mechanism of SNe Ia and details of the progenitor system remain controversial (Arnett, 1969; Khokhlov, 1991; Reinecke et al., 2002; Plewa et al., 2004; Röpke, 2007; Pakmor et al., 2011, 2012; Seitenzahl et al., 2013; Maoz et al., 2014; Seitenzahl et al., 2016; Branch & Wheeler, 2017; Gronow et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2021).

Benetti et al. (2005) suggest that normal SNe Ia can be classified into three classes: FAINT SNe Ia, high velocity gradient (HVG) SNe Ia, and low velocity gradient (LVG) SNe Ia, based on the temporal velocity gradient of Si ii, while Wang et al. (2009) suggest that SNe Ia can be divided into two subclasses, normal velocity (NV) SNe Ia and high velocity (HV) SNe Ia, based on the Si ii 6355 expansion velocity near the -band maximum. In addition to having ejecta with higher velocities ( 11,800 km s-1), HV SNe Ia also show a redder peak color, and a slower -band decline rate than those of NV SNe Ia (Wang et al., 2009; Foley & Kasen, 2011; Foley et al., 2011; Foley, 2012; Mandel et al., 2014; Childress et al., 2014). As for the differences between these two subclasses, they could result from a geometric effect of explosion asymmetry and viewing angle (Maund et al., 2010; Maeda et al., 2010; Parrent et al., 2011; Maeda et al., 2011). A recent study by Polin et al. (2019) has another, highly plausible, explanation for the high velocities and redder colors. They suggest that the differences are likely to be a natural byproduct of the double detonation model. Furthermore, the HV SNe Ia tend to reside in the large and massive galaxies, and usually arise in the inner, brighter, and metal-rich areas of their host galaxies, based on the analysis of the circumstellar environment of SNe Ia (Wang et al., 2013; Pan et al., 2015; Pan, 2020; Li et al., 2021).

The unresolved explosion mechanism and the diversity of SNe Ia relative to the circumstellar environment would directly affect the accuracy of the distance measurement of distant objects in the universe. Therefore, more and earlier photometric and spectroscopic data of SNe Ia are necessary. Fortunately, different models and mechanisms of SNe Ia progenitors exhibit significant differences when observed at their early stages, which is crucial to constrain the progenitors of the SNe Ia. The extra emission at early times could be produced by the interaction between the ejecta and the nondegenerate companion star (Kasen, 2010), and can account for the energetic mixing of radioactive 56Ni in the ejecta (Hosseinzadeh et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2018). The extra emission would appear as a ”bump” feature in the early light curves, which contain valuable information about the mass-loss history of the progenitor system, but which will be inaccessible a few days later on account of the destruction of its ejecta (Yang et al., 2020). The bump feature, which suggests that SNe Ia may originate from SD progenitor systems, has possibly been detected in some SNe Ia. Examples include SN 2012cg (Marion et al., 2016; Shappee et al., 2018), iPTF14atg with an ultraviolet (UV) excess (Kromer et al., 2016), iPTF16abc (Miller et al., 2018), MUSSES1604d with an early red flux excess (Jiang et al., 2017), SN 2017cbv with a resolved blue bump (Hosseinzadeh et al., 2017; Sand et al., 2018), SN 2017fgc (Zeng et al., 2021), SN 2018aoz with a faint excess in the and bands but a plateau in the band during its infant phase (Ni et al., 2022), SN 2018byg with a bump that could result from an SD and interaction or a DD and Ni mixing (De et al., 2019), SN 2018oh with a pronounced initial flux excess (Li et al., 2019; Shappee et al., 2019; Dimitriadis et al., 2019), and SN 2019yvq with an early bright UV excess (Burke et al., 2021).

In this article, we present the optical photometric and spectroscopic observations of Type Ia SN 2021hpr. Observations and data reductions are introduced in Section 2. Section 3 presents the optical light curves and the evolution of the spectra. The comparison of the light/color curves and spectra with those of other SN Ia, and the properties of the host galaxy are discussed in Section 4. The conclusion is given in Section 5.

2 Observations and Data Reductions

SN 2021hpr was discovered by Koichi Itagaki (Itagaki, 2021) at 10:46:28 on 2021 April 2 (UT dates are used throughout this paper) with an unfiltered magnitude of 17.7 mag. As shown in Figure 1, SN 2021hpr is located at west and south of the nucleus of the host galaxy NGC 3147, and its coordinates are , (J2000.0) (Itagaki, 2021). The - and -band light curves of SN 2021hpr (of which the first detection start from 2021 April 1) shown in the ALeRCE (Förster et al., 2021) explorer web interface 111alerce.online suggest that the luminosity of SN 2021hpr is rising rapidly. In addition, the ALeRCE stamp classifier (Förster et al., 2021) based on a convolutional neural network shows that SN 2021hpr has a high probability to be an SN. The first spectrum of SN 2021hpr taken at 19:48:36 on 2021 April 2 shows an expansion velocity of about 21,000 km s-1 as measured from the broad Si ii absorption, which is consistent with that of SNe Ia (Tomasella et al., 2021).

2.1 Photometry

The -band photometric observations of SN 2021hpr were carried out by using the 60cm telescope at XingLong Observatory, National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC). The telescope is equipped with a 2048 2048 pixel CCD, giving a field of view (FOV) of (pixel scale ). The photometric data were obtained from 2021 April 3 (two days after discovery) to 2021 June 3, covering the peak phase and including 26 observing nights. The observations of SN 2021hpr followed the sequence of , , , and filters and usually were repeated three times in each observation night. Since SN 2021hpr is located in one spiral arm of its host galaxy, the contamination due to the galaxy should be removed carefully. The template images of the host galaxy were obtained about 240 days after the SN explosion, when the SN was faint.

The ccdproc package (Craig et al., 2021) was employed to do the bias subtraction and flat field correction of the SN images. Generally, the combined bias frames and combined twilight flat fields taken on the same night were adopted. Cosmic rays were removed using LACosmic (van Dokkum, 2001). After these processes, astrometric calibrations of SN images were conducted by using Astrometry.net (Lang et al., 2012). Then, the SN images observed each day with the same filter (usually three images) were combined using the reproject package (Robitaille et al., 2020) and the ccdproc package. The template images obtained on 2021 December 24 were subtracted from the SN images after aligning. The point-spread functions (PSFs) of these two images were matched by adopting a Gaussian convolution, and the fluxes of the template images were scaled to the SN image by utilizing the fluxes of the same field stars in these two images.

Aperture photometry was performed on the template-subtracted images to acquire the instrumental magnitude of SN 2021hpr and of the local reference stars. These reference stars were used to calibrate the instrument magnitude to the standard Johnson (Johnson et al., 1966) and KronCousins (Cousins, 1980) systems. The magnitudes of the six reference stars (see Figure 1) are given in Table 2 of Biscardi et al. (2012). Here, we give the final photometry result of SN 2021hpr in Table 1.

The magnitudes errors take into account the Poisson noise of the target signal, the noise from image combination, the noise from the photometric calibration, and the noise of the sky background.

2.2 Spectroscopy

The optical spectra of SN 2021hpr were obtained with the Beijing Faint Object Spectrograph and Camera (BFOSC) attached to the 2.16m telescope at XingLong Observatory, NAOC (Fan et al., 2016). A grism of G4 + 385LP with a wavelength range of to and a slit width of was used for all the observations. The spectral resolution is about 20 , determined from the sky emission lines.

The spectroscopic observations were carried out from 2021 April 3 to June 20, covering the peak phase, and a total of six spectra were obtained. The spectra of the SN and a standard star were obtained at a similar airmass for flux calibration. The log of the spectroscopic observations is given in Table 2. The spectral data were reduced using standard IRAF routines, including bias subtraction, flat correction, and cosmic-rays removal. The SN 2021hpr spectra were wavelength calibrated using observations of an FeAr lamp taken in the dome on the same night. Additionally, a spectrum of the nucleus of NGC 3147 was observed on 2022 February 1 using BFOSC with the same grism and slit in order to analyze the host galaxy of SN 2021hpr, and it will be discussed in section 4.4.

3 Optical Light Curves and Spectra of SN 2021hpr

3.1 Optical Light Curves

The optical light curves of SN 2021hpr in the bands are shown in Figure 2, covering the phases from 14.37 to +46.67 days relative to the -band maximum. The photometric evolution of SN 2021hpr is consistent with that of typical normal SNe Ia. A plateau is evident in the -band light curve from t +18 to +25 days relative to peak luminosity, while a secondary hump is seen in the -band light curve. The -band magnitudes around maximum light were fitted using a second-order polynomial to estimate the -band peak magnitude, which is mag on MJD . The -band peak magnitude is on MJD , which is about 1.4 days later. The peak magnitudes and corresponding MJDs of the bands are calculated and listed in Table 3. The post-maximum magnitude decline rate ; (Phillips, 1993) is estimated by SNooPy (Burns et al., 2011) to be mag. It is slightly lower than the typical value of 1.1 mag (Phillips et al., 1999), but still in the range for SNe Ia of 0.751.94 (Krisciunas et al., 2003).

The rise time represents the time from explosion to maximum luminosity, and is dependent on the progenitors of SNe Ia (Leibundgut & Pinto, 1992). Assuming SN 2021hpr exploded like an expanding fireball, with a constant temperature and velocity, its luminosity or flux should be proportional to the second power of time (Riess et al., 1999). The rise time can be obtained from the relation:

| (1) |

where represents the phase relative to the -band maximum and describes the velocity of the rising flux. This relationship is consistent with the SNe light-curve patterns of some sky surveys (i.e., Riess et al., 1999; Goldhaber et al., 2001; Conley et al., 2006; Garg et al., 2007; Hayden et al., 2010; Ganeshalingam et al., 2011; Firth et al., 2015) and of some well-sampled individual SNe Ia (i.e., SN 2011fe, Nugent et al., 2011).

Based on Equation (1), the rise time of SN 2021hpr can be derived as days by fitting the data from the first observation day to 8 days. The data taken on 2021 April 3 were not included for data fitting due to the large errors.

3.2 Evolution of the Spectra

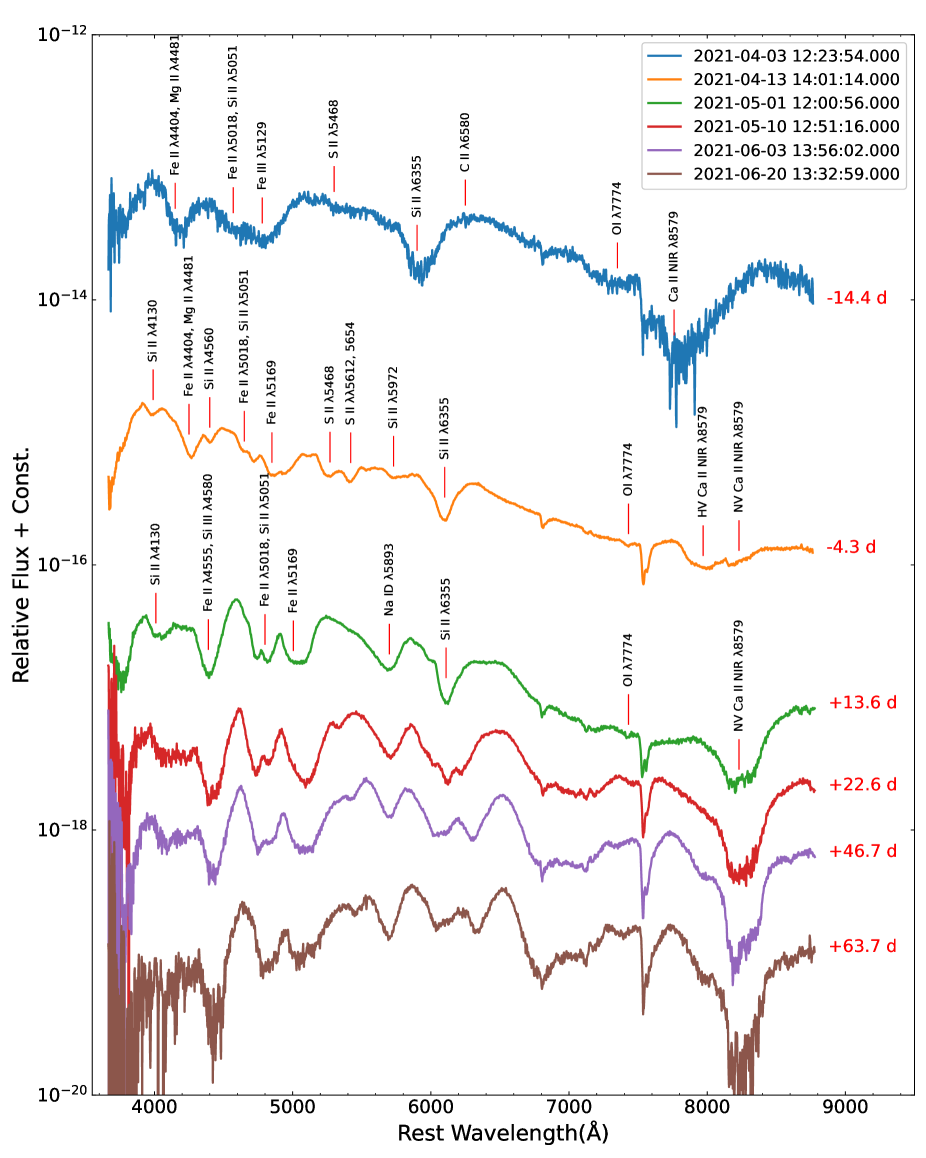

The spectral sequence of SN 2021hpr is shown in Figure 3. A total of six optical low-resolution spectra cover the phases from 14.37 days to +63.68 days relative to the -band maximum. The redshift of the host galaxy was corrected for in all spectra. The first spectrum of SN 2021hpr obtained at t 14.37 days is the earliest one among all publicly available spectra.

In the first spectrum of SN 2021hpr, the absorption lines are mainly those of intermediate-mass elements, such as Mg ii, Si ii, S ii, and Ca ii. The most distinct features characterized by Si ii 6355 and the Ca ii NIR triplet (8498, 8542, and 8662 ) are broad and strong with a very large velocity, and they can be clearly identified near 5900 and 7800 , respectively. The blended features of Fe ii 4404 and Mg ii 4481 can be found near 4200 , and the broad absorption feature near 4700 could be caused by Fe ii 5018, Si ii 5051 and Fe iii 5129. The weak feature near 7400 should be O i 7774. No apparent Na I D doublet lines could be identified in the spectrum, which indicates that the interstellar extinction can be ignored.

At days, the characteristic of Si ii 4130 feature appeared in the spectrum, and the absorption features of Fe ii 4404, Mg ii 4481, Si iii 4560, Fe ii 5018, Si ii 5051 and Fe iii 5129 became more obvious and more recognizable. The ”W” shape consisting of S ii 5468 and S ii 5612,5654 emerged. Si ii 5972 should be responsible for the absorption line near 5700 . The expansion velocity of Si ii 6355 decreased rapidly. The HV component can be distinguished from the NV component of the Ca ii NIR triplet, of which the velocity became smaller.

Two weeks after the maximum luminosity, at days, the absorption feature of Si iii 4560 became weaker, and the ”W” shape almost disappeared. Near 5700 , a strong absorption feature could be identified as Na I D 5893, while the absorption feature of Si ii 5972 was barely visible. The expansion velocity of the Ca ii NIR triplet decreased further.

From the third week to the second month since peak luminosity, according to the spectra observed at t 22.6, 46.7, and 63.7 days, the iron-peak element features became stronger and gradually dominated the spectrum. The absorption feature of Si ii 6355 became weaker, while the Fe ii lines gradually appeared.

4 Analysis and Discussion

4.1 Light-Curve Comparison

In Figure 4, the -band light curves of SN 2021hpr are plotted with those of other SNe Ia, which are ASASSN-14bd (Brown et al., 2014), SN 2017cbv (Wang et al., 2020), SN 2003du (Anupama et al., 2005; Stanishev et al., 2007; Hicken et al., 2009; Ganeshalingam et al., 2010; Silverman et al., 2012), SN 2005cf (Pastorello et al., 2007; Hicken et al., 2009; Ganeshalingam et al., 2010; Silverman et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2014), SN 2009ig (Brown et al., 2012; Hicken et al., 2012; Silverman et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2014; Stahl et al., 2019), SN 2011fe (Richmond & Smith, 2012; Silverman et al., 2012; Tsvetkov et al., 2013; Munari et al., 2013; Brown et al., 2014; Stahl et al., 2019), and SN 2018oh (Li et al., 2019). The first two SNe Ia have a flux excess in their early phase, while the others are normal SNe Ia. The light curves of all samples are normalized to their peaks. It can be seen that the -band light curve of SN 2021hpr has a similar shape to that of other normal SNe Ia in the phase before the maximum luminosity. The decline rate of SN 2021hpr (see Section 3.1) is close to the mag of SN 2008oh (Li et al., 2019), mag of SN 2009ig (Foley et al., 2012), and mag of SN 2017cbv (Wang et al., 2020). The decline rate is slower than that of SN 2011fe, which has a typical value for the decline rate of mag, while its luminosity is brighter. After +30 days, the -band luminosity is relatively brighter than those of other SNe Ia during the same phase. The -band light curves of SN 2021hpr follow the evolution of other normal SNe Ia. The second maximum in the band of SN 2021hpr is slightly stronger than those of other SNe Ia. Furthermore, ASASSN-14bd (in -band) and SN 2017cbv are brighter than the others before reaching the maximum.

4.2 The Reddening and Color Evolution

In Figure 5, , , and color curves of SN 2021hpr are compared with those of the other SNe Ia in Section 4.1, except for ASASSN-14bd because it lacks data in the -band. All the color curves have been corrected for the Galactic and host galaxy reddening. As for SN 2021hpr, the Galactic extinction is estimated to be mag, mag, mag and mag on the basis of the dust map of the Milky Way (Schlafly & Finkbeiner, 2011). The host galaxy extinction of SN 2021hpr is almost negligible, which will be discussed in Section 4.4.

From to +20 days, the color evolution of SN 2021hpr shows a resemblance to most of the selected SNe, while after +20 days the color is bluer than most of the other supernovae. SN 2021hpr reaches the bluest color of 0.06 mag at days, then gradually turns into its reddest color of mag at days. SN 2017cbv is an SN Ia with early excess. Its color before the -band maximum is bluer than that of most of the normal SNe, including SN 2021hpr, which suggests that SN 2021hpr may not have a bump feature in early phase. Before reaching maximum luminosity, the color curve of SN 2021hpr has a plateau phase at mag, which is similar to that of SN 2017cbv. However, the latter starts to decline after t days. The color of SN 2021hpr reaches the minimum value of approximately mag, and undergoes rapid reddening until it reaches the reddest color of mag at days. The color of SN 2021hpr is similar to that of SN 2011fe. SN 2021hpr reaches its bluest ( mag) at days and its reddest ( mag) at days. In addition, the color of SN 2021hpr is redder than that of most of the selected SNe after days.

4.3 Spectra Comparison and Spectroscopic Properties

In Figure 6, we compare the spectra of SN 2021hpr with that of 2011fe at four different epochs (t 14, 4, +13 and +70 days relative to the -band maximum). All the spectra have been corrected for redshift. In addition, the spectra of SN 2021hpr before or near peak luminosity downloaded from the Transient Name Server (TNS) website are also added into comparison, and are shown in Figure 6a and Figure 6b. Furthermore, we obtained the velocity of Si ii 6355 of SN 2021hpr by Gaussian fitting.

At t days, the spectra of SN 2021hpr obtained by 2.16 m telescope are similar to the spectra from TNS, but shifted nearly half a day earlier (see Figure 6a). The expansion velocity of Si ii 6355 of the former reaches 20,440 km s-1, which is slightly higher than that in the latter spectrum from TNS. SN 2021hpr shows a very high velocity for the Ca ii NIR triplet, which is nearly 28,000 km s-1. The velocities of these two features are much higher than those of SN 2011fe at this phase. A weak absorption feature of C ii 6580 is seen on the redder side of Si ii 6355 in the spectrum of SN 2011fe, while no obvious carbon feature can be recognized in the spectrum of SN 2021hpr. At least 30 of SNe would show lines of carbon in their spectra before the luminosity reaches maximum (Thomas et al., 2011).

About four days before maximum (Figure 6b), the Si ii 6355 velocity of SN 2021hpr decreased more rapidly to 12,420 km s-1. The velocity gradient from to days is about 800 km s-1 day-1, which confirms that SN 2021hpr belongs to the HVG SNe Ia group. Even so, this velocity is still higher than that of SN 2011fe and other NV SNe Ia, whose velocity is about 11,800 km s-1 (Wang et al., 2009). This indicates that SN 2021hpr should be a transitional object between the HV and Normal groups, which is also confirmed by the slower -band decline rate (see 3.1). An HV component of the Ca ii NIR triplet absorption profile can be found in the spectrum of SN 2021hpr, which is similar to that of SN 2011fe. The velocity range of this absorption feature is between 14,000 and 20,000 km s-1, which is higher than that of SN 2011fe. The blended feature composed of Fe ii 4404 and Mg ii 4481 seems stronger in the spectrum of SN 201hpr than that in that of SN 2011fe.

Figure 6c displays the spectra two weeks after maximum luminosity. The Si ii and Ca ii absorption features still remain, while the ”W” shape of S ii has almost disappeared. The Si ii 6355 velocity of SN 2021hpr is also slightly higher than that of SN 2011fe. Figure 6d shows the spectra two months after maximum luminosity. SN 2021hpr and SN 2011fe show comparable absorption features in their spectra, and the Fe features became dominant. The Ca ii NIR triplet absorption feature is still very strong in both spectra.

4.4 Host Galaxy

NGC 3147 is a face-on spiral galaxy and classified as SA(rs)bc (Blanc et al., 2013) with a redshift of 0.00935 and a size of about . Its apparent magnitude in the band is 10.61 mag (Gil de Paz et al., 2007). Panessa & Bassani (2002) classified it as a type II Seyfert galaxy. However, a recent study discovered very broad emission lines in its nucleus (Bianchi et al., 2019), suggesting that it is a low accretion rate type I active galactic nucleus with a massive black hole.

We observed the nucleus of NGC 3147 with BFOSC on 2022 February 1, as shown in Figure 7. The H region of the spectrum is shown in Figure 8. The ratio of H and [N ii] 6584 suggests that NGC 3147 could be classified as a low-ionization nuclear emission-line region (LINER).

NGC 3147 is also an SNe factory in which six SNe have been observed over the past 50 yr (1972-2022): SN 1972H (Patat et al., 1997), SN 1997 (Jha et al., 2006), SN 2006gi (Duszanowicz, 2006), SN 2008fv (Tsvetkov & Elenin, 2010), SN 2021do, and SN 2021hpr. Four of them are SNe Ia, one is an SN Ib, and one is an SN Ic. In Table 4, we summarize the SN type and equatorial coordinates (J2000) of these SNe, whose locations are shown in Figure 9. Interestingly, the four SNe Ia are all located in the galactic disk, while the Type Ic SN 2021do is closest to the galactic nucleus, and the Type Ib SN 2006gi is the farthest from the galactic center, in the outskirt of the galactic disk.

According to the statistics of Thöne et al. (2009), there are more than 16 galaxies in which SNe have been detected more than four times. The highest record is still held by NGC 6946, where 10 SNe have been observed in recent decades. It is followed by NGC 4303 with eight SNe, NGC 3690 with seven SNe, and then NGC 3147 with six SNe. The SN explosion rate in NGC 3147 is high if compared to the average of about three per galaxy per century. Using radio data, Thöne et al. (2009) estimates the SN explosion rate of NGC 3147 as 0.18 SNe per year, with 0.06 per year for Type Ia, 0.09 per year for Type Ibc, and 0.03 per year for Type II. On average, three SNe Ia, 4.5 SNe Ibc, and 1.5 SNe II will explode in NGC 3147 every 50 yr. Therefore, the observed explosion rate is slightly higher than that expected for SNe Ia in NGC 3147, but much lower for SNe Ibc and SNe II.

Furthermore, we examined the metallicity of the surroundings of SN 2021hpr. Figure 10 shows the spectrum combined with spectra of three star-formation regions within the distance of SN 2021hpr of 30′′. The flux ratio of decomposed H and H is estimated to be . Therefore, the host galaxy extinction of SN 2021hpr is negligible. The spectrum near 6600 displayed in Figure 10 is shown in Figure 11, where it exhibits features of [N ii] 6584 and H 6563. Since the two emission lines are blended, we use double Gaussian fitting to derive the flux ratio as [N ii] 6584/H 6563 0.33, corresponding to the metallicity of 12+log(O/H) 8.648, comparable to the solar metallicity of 8.69 (Asplund et al., 2021). This is consistent with the suggestion by Pan (2020) that HV SNe might be present in massive galaxies with metal-rich environments.

Based on the redshift of NGC 3147, we can obtain the the distance modulus of .222Given by the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (2019), NED), assuming = 67.8 km s -1 Mpc-1 (Virgo Infall only) and However, in the local universe, measurements need a better “standard candle,” such as SNe Ia. The distance modulus of NGC 3147 can be calculated if we know the absolute magnitude of SN 2021hpr. Based on the decline rate mag (see Section 3.1) and the Phillips relation (Phillips et al. 1999; e.g., Wu et al. 1995), we can derive mag. Then, the distance modulus should be = mag, which is the same as the result of Jha et al. (2007) ( = mag), who measured the distance modulus for SN 1997bq using the multicolor light-curve shape method (MLCS2K2). However, the distance moduli vary from 32.41 mag to 33.46 mag even when measured from the same SNe (e.g. SN 1997bq; Reindl et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2006; Prieto et al., 2006; Jha et al., 2007; Kowalski et al., 2008; Takanashi et al., 2008; Amanullah et al., 2010; Tully et al., 2013). While differences in the final result could be due to different physics, distance modulus measurements can be also affected by many other factors, such as photometric accuracy, internal reddening of the host galaxy, and template subtraction.

To search for the progenitor of SN 2021hpr, we inspected the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) images before and after (see Figure 12) SN 2021hpr exploded, and we failed to detect it. However, we can obtain an upper limit (3) for it of 28.50 mag, 28.35 mag and 27.87 mag (AB) in the WFC3/F350LP, WFC3/F555W and WFC3/F814W bands, respectively. Using the distance modulus obtained above, we calculate that the absolute magnitudes of the progenitor of SN 2021hpr should be fainter than -4.96 mag , -5.11 mag, and -5.59 mag in the above three bands.

5 Conclusion

In this article, we present the optical photometry and spectroscopy of SN 2021hpr, especially the early spectrum obtained at days before the maximum. All photometric and spectroscopic data will be available on WISeREP3 (Yaron & Gal-Yam, 2012). The derived photometric parameters of SN 2021hpr are listed in Table Optical Observations of the Nearby Type Ia Supernova 2021hpr. We draw the following conclusions.

(1) The light curves show that SN 2021hpr is a normal type Ia SN. Its light-curve evolution resembles that of some well-sampled SNe Ia. SN 2021hpr has a rise time days, and a post-maximum magnitude decline rate mag, which is lower than the typical value for normal SNe Ia. By about two weeks before maximum, there was no flux excess detected in the optical light curves of SN 2021hpr.

(2) The color evolution of SN 2021hpr is similar to that of some well-sampled SNe Ia during most of the time, except for a plateau phase that appeared in color curve before it reached the peak luminosity, which is similar to that of SN 2017cbv.

(3) The expansion velocity of Si ii of SN 2021hpr is about 12,420 km s-1 at 4.31 days, which is slightly higher than that of NV SNe Ia, indicating that SN 2021hpr might be a transitional object between HV and NV SNe Ia. SN 2021hpr is also an HVG SN Ia, whose velocity gradient of Si ii reached 800 km s-1 day-1 from to days relative to the -band maximum.

(4) Including SN 2021hpr, there have been six SNe observed in NGC 3147 over the past 50 yr. Compared with the estimation by Thöne et al. (2009), the SN rate of NGC 3147 in the past 50 yr is somewhat higher than expected for SNe Ia, but lower for SNe Ibc and SNe II.

(5) Based on the ratio of [N ii] 6584 and H 6563 of the star-formation regions near SN 2021hpr, the circumstellar environment of SN 2021hpr is metal-rich (12 + log(O/H) 8.648), comparable to the solar metallicity. This supports the idea that metal-rich environments are ideal sites for HV SNe.

(6) The distance modulus of the host galaxy NGC 3147 is calculated to be 33.46 0.21 mag according to the light curve of SN 2021hpr, consistent with measures for the other SNe Ia in this galaxy.

To explore the progenitor system, it is necessary to detect a large sample of SNe Ia in the earliest phase. The future SiTian Project promoted by NAOC (Liu et al., 2021) will provide us such an opportunity.

References

- Amanullah et al. (2010) Amanullah, R., Lidman, C., Rubin, D., et al. 2010, ApJ, 716, 712, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/716/1/712

- Anupama et al. (2005) Anupama, G. C., Sahu, D. K., & Jose, J. 2005, A&A, 429, 667, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:20041687

- Arnett (1969) Arnett, W. D. 1969, Ap&SS, 5, 180, doi: 10.1007/BF00650291

- Asplund et al. (2021) Asplund, M., Amarsi, A. M., & Grevesse, N. 2021, A&A, 653, A141, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202140445

- Astropy Collaboration et al. (2013) Astropy Collaboration, Robitaille, T. P., Tollerud, E. J., et al. 2013, A&A, 558, A33, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322068

- Astropy Collaboration et al. (2018) Astropy Collaboration, Price-Whelan, A. M., Sipőcz, B. M., et al. 2018, AJ, 156, 123, doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/aabc4f

- Benetti et al. (2005) Benetti, S., Cappellaro, E., Mazzali, P. A., et al. 2005, ApJ, 623, 1011, doi: 10.1086/428608

- Bianchi et al. (2019) Bianchi, S., Antonucci, R., Capetti, A., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 488, L1, doi: 10.1093/mnrasl/slz080

- Biscardi et al. (2012) Biscardi, I., Brocato, E., Arkharov, A., et al. 2012, A&A, 537, A57, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201014160

- Blanc et al. (2013) Blanc, G. A., Weinzirl, T., Song, M., et al. 2013, AJ, 145, 138, doi: 10.1088/0004-6256/145/5/138

- Bochenek et al. (2018) Bochenek, C. D., Dwarkadas, V. V., Silverman, J. M., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 473, 336, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stx2029

- Bradley et al. (2020) Bradley, L., Sipőcz, B., Robitaille, T., et al. 2020, astropy/photutils: 1.0.0, 1.0.0, Zenodo, doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4044744

- Branch & Wheeler (2017) Branch, D., & Wheeler, J. C. 2017, Supernova Explosions, doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-55054-0

- Brown et al. (2014) Brown, P. J., Breeveld, A. A., Holland, S., Kuin, P., & Pritchard, T. 2014, Ap&SS, 354, 89, doi: 10.1007/s10509-014-2059-8

- Brown et al. (2012) Brown, P. J., Dawson, K. S., Harris, D. W., et al. 2012, ApJ, 749, 18, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/749/1/18

- Burke et al. (2021) Burke, J., Howell, D. A., Sarbadhicary, S. K., et al. 2021, ApJ, 919, 142, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ac126b

- Burns et al. (2011) Burns, C. R., Stritzinger, M., Phillips, M. M., et al. 2011, AJ, 141, 19, doi: 10.1088/0004-6256/141/1/19

- Burns et al. (2014) —. 2014, ApJ, 789, 32, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/789/1/32

- Burns et al. (2018) Burns, C. R., Parent, E., Phillips, M. M., et al. 2018, ApJ, 869, 56, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aae51c

- Cao et al. (2015) Cao, Y., Kulkarni, S. R., Howell, D. A., et al. 2015, Nature, 521, 328, doi: 10.1038/nature14440

- Childress et al. (2014) Childress, M. J., Filippenko, A. V., Ganeshalingam, M., & Schmidt, B. P. 2014, MNRAS, 437, 338, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stt1892

- Conley et al. (2006) Conley, A., Howell, D. A., Howes, A., et al. 2006, AJ, 132, 1707, doi: 10.1086/507788

- Côté et al. (2016) Côté, B., Ritter, C., O’Shea, B. W., et al. 2016, ApJ, 824, 82, doi: 10.3847/0004-637X/824/2/82

- Cousins (1980) Cousins, A. W. J. 1980, South African Astronomical Observatory Circular, 1, 234

- Craig et al. (2017) Craig, M., Crawford, S., Seifert, M., et al. 2017, astropy/ccdproc: v1.3.0.post1, doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1069648

- Craig et al. (2021) —. 2021, astropy/ccdproc: 2.3.0 – cosmic ray update, 2.3.0, Zenodo, doi: 10.5281/zenodo.5796852

- De et al. (2019) De, K., Kasliwal, M. M., Polin, A., et al. 2019, ApJ, 873, L18, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ab0aec

- Dilday et al. (2012) Dilday, B., Howell, D. A., Cenko, S. B., et al. 2012, Science, 337, 942, doi: 10.1126/science.1219164

- Dimitriadis et al. (2019) Dimitriadis, G., Foley, R. J., Rest, A., et al. 2019, ApJ, 870, L1, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aaedb0

- Duszanowicz (2006) Duszanowicz, G. 2006, IAU Circ., 8755, 3

- Dwek (1998) Dwek, E. 1998, ApJ, 501, 643, doi: 10.1086/305829

- Fan et al. (2016) Fan, Z., Wang, H., Jiang, X., et al. 2016, PASP, 128, 115005, doi: 10.1088/1538-3873/128/969/115005

- Firth et al. (2015) Firth, R. E., Sullivan, M., Gal-Yam, A., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 446, 3895, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stu2314

- Foley (2012) Foley, R. J. 2012, ApJ, 748, 127, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/748/2/127

- Foley & Kasen (2011) Foley, R. J., & Kasen, D. 2011, ApJ, 729, 55, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/729/1/55

- Foley et al. (2011) Foley, R. J., Sanders, N. E., & Kirshner, R. P. 2011, ApJ, 742, 89, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/742/2/89

- Foley et al. (2012) Foley, R. J., Challis, P. J., Filippenko, A. V., et al. 2012, ApJ, 744, 38, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/744/1/38

- Förster et al. (2021) Förster, F., Cabrera-Vives, G., Castillo-Navarrete, E., et al. 2021, AJ, 161, 242, doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/abe9bc

- Freedman et al. (2019) Freedman, W. L., Madore, B. F., Hatt, D., et al. 2019, ApJ, 882, 34, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab2f73

- Ganeshalingam et al. (2011) Ganeshalingam, M., Li, W., & Filippenko, A. V. 2011, MNRAS, 416, 2607, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19213.x

- Ganeshalingam et al. (2010) Ganeshalingam, M., Li, W., Filippenko, A. V., et al. 2010, ApJS, 190, 418, doi: 10.1088/0067-0049/190/2/418

- Garg et al. (2007) Garg, A., Stubbs, C. W., Challis, P., et al. 2007, AJ, 133, 403, doi: 10.1086/510118

- Gil de Paz et al. (2007) Gil de Paz, A., Boissier, S., Madore, B. F., et al. 2007, ApJS, 173, 185, doi: 10.1086/516636

- Goldhaber et al. (2001) Goldhaber, G., Groom, D. E., Kim, A., et al. 2001, ApJ, 558, 359, doi: 10.1086/322460

- Gronow et al. (2020) Gronow, S., Collins, C., Ohlmann, S. T., et al. 2020, A&A, 635, A169, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201936494

- Guy et al. (2005) Guy, J., Astier, P., Nobili, S., Regnault, N., & Pain, R. 2005, A&A, 443, 781, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:20053025

- Harris et al. (2020) Harris, C. R., Millman, K. J., van der Walt, S. J., et al. 2020, Nature, 585, 357, doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2649-2

- Hayden et al. (2010) Hayden, B. T., Garnavich, P. M., Kessler, R., et al. 2010, ApJ, 712, 350, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/712/1/350

- Hicken et al. (2009) Hicken, M., Challis, P., Jha, S., et al. 2009, ApJ, 700, 331, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/700/1/331

- Hicken et al. (2012) Hicken, M., Challis, P., Kirshner, R. P., et al. 2012, ApJS, 200, 12, doi: 10.1088/0067-0049/200/2/12

- Hosseinzadeh et al. (2017) Hosseinzadeh, G., Sand, D. J., Valenti, S., et al. 2017, ApJ, 845, L11, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aa8402

- Hunter (2007) Hunter, J. D. 2007, Computing in Science & Engineering, 9, 90, doi: 10.1109/MCSE.2007.55

- Iben & Tutukov (1984) Iben, I., J., & Tutukov, A. V. 1984, ApJS, 54, 335, doi: 10.1086/190932

- Itagaki (2021) Itagaki, K. 2021, Transient Name Server Discovery Report, 2021-998, 1

- Jha et al. (2007) Jha, S., Riess, A. G., & Kirshner, R. P. 2007, ApJ, 659, 122, doi: 10.1086/512054

- Jha et al. (2006) Jha, S., Kirshner, R. P., Challis, P., et al. 2006, AJ, 131, 527, doi: 10.1086/497989

- Jiang et al. (2017) Jiang, J.-A., Doi, M., Maeda, K., et al. 2017, Nature, 550, 80, doi: 10.1038/nature23908

- Johnson et al. (1966) Johnson, H. L., Mitchell, R. I., Iriarte, B., & Wisniewski, W. Z. 1966, Communications of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, 4, 99

- Kasen (2010) Kasen, D. 2010, ApJ, 708, 1025, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/708/2/1025

- Khokhlov (1991) Khokhlov, A. M. 1991, A&A, 245, 114

- Kobayashi & Nomoto (2009) Kobayashi, C., & Nomoto, K. 2009, ApJ, 707, 1466, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/707/2/1466

- Kobayashi et al. (1998) Kobayashi, C., Tsujimoto, T., Nomoto, K., Hachisu, I., & Kato, M. 1998, ApJ, 503, L155, doi: 10.1086/311556

- Kowalski et al. (2008) Kowalski, M., Rubin, D., Aldering, G., et al. 2008, ApJ, 686, 749, doi: 10.1086/589937

- Krisciunas et al. (2003) Krisciunas, K., Suntzeff, N. B., Candia, P., et al. 2003, AJ, 125, 166, doi: 10.1086/345571

- Kromer et al. (2016) Kromer, M., Fremling, C., Pakmor, R., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 459, 4428, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw962

- Lacchin et al. (2021) Lacchin, E., Calura, F., & Vesperini, E. 2021, MNRAS, 506, 5951, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stab2061

- Lang et al. (2012) Lang, D., Hogg, D. W., Mierle, K., Blanton, M., & Roweis, S. 2012, Astrometry.net: Astrometric calibration of images. http://ascl.net/1208.001

- Leibundgut & Pinto (1992) Leibundgut, B., & Pinto, P. A. 1992, ApJ, 401, 49, doi: 10.1086/172037

- Li et al. (2011) Li, W., Bloom, J. S., Podsiadlowski, P., et al. 2011, Nature, 480, 348, doi: 10.1038/nature10646

- Li et al. (2019) Li, W., Wang, X., Vinkó, J., et al. 2019, ApJ, 870, 12, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aaec74

- Li et al. (2021) Li, W., Wang, X., Bulla, M., et al. 2021, ApJ, 906, 99, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/abc9b5

- Liu et al. (2021) Liu, J., Soria, R., Wu, X.-F., Wu, H., & Shang, Z. 2021, An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. vol.93 supl.1, 93, 20200628, doi: 10.1590/0001-3765202120200628

- Lundqvist et al. (2015) Lundqvist, P., Nyholm, A., Taddia, F., et al. 2015, A&A, 577, A39, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201525719

- Maeda et al. (2010) Maeda, K., Benetti, S., Stritzinger, M., et al. 2010, Nature, 466, 82, doi: 10.1038/nature09122

- Maeda et al. (2011) Maeda, K., Leloudas, G., Taubenberger, S., et al. 2011, MNRAS, 413, 3075, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18381.x

- Maguire et al. (2013) Maguire, K., Sullivan, M., Patat, F., et al. 2013, MNRAS, 436, 222, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stt1586

- Mandel et al. (2014) Mandel, K. S., Foley, R. J., & Kirshner, R. P. 2014, ApJ, 797, 75, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/797/2/75

- Maoz et al. (2014) Maoz, D., Mannucci, F., & Nelemans, G. 2014, ARA&A, 52, 107, doi: 10.1146/annurev-astro-082812-141031

- Marion et al. (2016) Marion, G. H., Brown, P. J., Vinkó, J., et al. 2016, ApJ, 820, 92, doi: 10.3847/0004-637X/820/2/92

- Maund et al. (2010) Maund, J. R., Höflich, P., Patat, F., et al. 2010, ApJ, 725, L167, doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/725/2/L167

- Miller et al. (2018) Miller, A. A., Cao, Y., Piro, A. L., et al. 2018, ApJ, 852, 100, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aaa01f

- Munari et al. (2013) Munari, U., Henden, A., Belligoli, R., et al. 2013, New A, 20, 30, doi: 10.1016/j.newast.2012.09.003

- NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (2019) (NED) NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED). 2019, NED Gravitational Wave Follow-up (GWF) Service, IPAC, doi: 10.26132/NED3

- National Optical Astronomy Observatories (1999) National Optical Astronomy Observatories. 1999, IRAF: Image Reduction and Analysis Facility, Astrophysics Source Code Library, record ascl:9911.002. http://ascl.net/9911.002

- Ni et al. (2022) Ni, Y. Q., Moon, D.-S., Drout, M. R., et al. 2022, Nature Astronomy, doi: 10.1038/s41550-022-01603-4

- Nugent et al. (2011) Nugent, P. E., Sullivan, M., Cenko, S. B., et al. 2011, Nature, 480, 344, doi: 10.1038/nature10644

- Olling et al. (2015) Olling, R. P., Mushotzky, R., Shaya, E. J., et al. 2015, Nature, 521, 332, doi: 10.1038/nature14455

- Pakmor et al. (2011) Pakmor, R., Hachinger, S., Röpke, F. K., & Hillebrandt, W. 2011, A&A, 528, A117, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201015653

- Pakmor et al. (2012) Pakmor, R., Kromer, M., Taubenberger, S., et al. 2012, ApJ, 747, L10, doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/747/1/L10

- Pan (2020) Pan, Y.-C. 2020, ApJ, 895, L5, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ab8e47

- Pan et al. (2015) Pan, Y. C., Sullivan, M., Maguire, K., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 446, 354, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stu2121

- Panessa & Bassani (2002) Panessa, F., & Bassani, L. 2002, A&A, 394, 435, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:20021161

- Parrent et al. (2011) Parrent, J. T., Thomas, R. C., Fesen, R. A., et al. 2011, ApJ, 732, 30, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/732/1/30

- Pastorello et al. (2007) Pastorello, A., Taubenberger, S., Elias-Rosa, N., et al. 2007, MNRAS, 376, 1301, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11527.x

- Patat et al. (1997) Patat, F., Barbon, R., Cappellaro, E., & Turatto, M. 1997, A&A, 317, 423. https://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/9605181

- Pereira et al. (2013) Pereira, R., Thomas, R. C., Aldering, G., et al. 2013, A&A, 554, A27, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201221008

- Perlmutter et al. (1999) Perlmutter, S., Aldering, G., Goldhaber, G., et al. 1999, ApJ, 517, 565, doi: 10.1086/307221

- Phillips (1993) Phillips, M. M. 1993, ApJ, 413, L105, doi: 10.1086/186970

- Phillips et al. (1999) Phillips, M. M., Lira, P., Suntzeff, N. B., et al. 1999, AJ, 118, 1766, doi: 10.1086/301032

- Plewa et al. (2004) Plewa, T., Calder, A. C., & Lamb, D. Q. 2004, ApJ, 612, L37, doi: 10.1086/424036

- Polin et al. (2019) Polin, A., Nugent, P., & Kasen, D. 2019, ApJ, 873, 84, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aafb6a

- Prieto et al. (2006) Prieto, J. L., Rest, A., & Suntzeff, N. B. 2006, ApJ, 647, 501, doi: 10.1086/504307

- Reindl et al. (2005) Reindl, B., Tammann, G. A., Sandage, A., & Saha, A. 2005, ApJ, 624, 532, doi: 10.1086/429218

- Reinecke et al. (2002) Reinecke, M., Hillebrandt, W., & Niemeyer, J. C. 2002, A&A, 391, 1167, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:20020885

- Richmond & Smith (2012) Richmond, M. W., & Smith, H. A. 2012, \jaavso, 40, 872. https://arxiv.org/abs/1203.4013

- Riess et al. (1999) Riess, A. G., Filippenko, A. V., Li, W., & Schmidt, B. P. 1999, AJ, 118, 2668, doi: 10.1086/301144

- Riess et al. (1996) Riess, A. G., Press, W. H., & Kirshner, R. P. 1996, ApJ, 473, 88, doi: 10.1086/178129

- Riess et al. (1998) Riess, A. G., Filippenko, A. V., Challis, P., et al. 1998, AJ, 116, 1009, doi: 10.1086/300499

- Riess et al. (2016) Riess, A. G., Macri, L. M., Hoffmann, S. L., et al. 2016, ApJ, 826, 56, doi: 10.3847/0004-637X/826/1/56

- Riess et al. (2018) Riess, A. G., Rodney, S. A., Scolnic, D. M., et al. 2018, ApJ, 853, 126, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aaa5a9

- Robitaille et al. (2020) Robitaille, T., Deil, C., & Ginsburg, A. 2020, reproject: Python-based astronomical image reprojection. http://ascl.net/2011.023

- Röpke (2007) Röpke, F. K. 2007, ApJ, 668, 1103, doi: 10.1086/520830

- Sand et al. (2018) Sand, D. J., Graham, M. L., Botyánszki, J., et al. 2018, ApJ, 863, 24, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aacde8

- Schlafly & Finkbeiner (2011) Schlafly, E. F., & Finkbeiner, D. P. 2011, ApJ, 737, 103, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/737/2/103

- Seitenzahl et al. (2013) Seitenzahl, I. R., Ciaraldi-Schoolmann, F., Röpke, F. K., et al. 2013, MNRAS, 429, 1156, doi: 10.1093/mnras/sts402

- Seitenzahl et al. (2016) Seitenzahl, I. R., Kromer, M., Ohlmann, S. T., et al. 2016, A&A, 592, A57, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201527251

- Shappee et al. (2018) Shappee, B. J., Piro, A. L., Stanek, K. Z., et al. 2018, ApJ, 855, 6, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aaa1e9

- Shappee et al. (2019) Shappee, B. J., Holoien, T. W. S., Drout, M. R., et al. 2019, ApJ, 870, 13, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aaec79

- Shen et al. (2021) Shen, K. J., Blondin, S., Kasen, D., et al. 2021, ApJ, 909, L18, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/abe69b

- Silverman et al. (2012) Silverman, J. M., Foley, R. J., Filippenko, A. V., et al. 2012, MNRAS, 425, 1789, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21270.x

- Silverman et al. (2013) Silverman, J. M., Nugent, P. E., Gal-Yam, A., et al. 2013, ApJS, 207, 3, doi: 10.1088/0067-0049/207/1/3

- Stahl et al. (2019) Stahl, B. E., Zheng, W., de Jaeger, T., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 490, 3882, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stz2742

- Stanishev et al. (2007) Stanishev, V., Goobar, A., Benetti, S., et al. 2007, A&A, 469, 645, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:20066020

- Sternberg et al. (2011) Sternberg, A., Gal-Yam, A., Simon, J. D., et al. 2011, Science, 333, 856, doi: 10.1126/science.1203836

- Takanashi et al. (2008) Takanashi, N., Doi, M., & Yasuda, N. 2008, MNRAS, 389, 1577, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13694.x

- Thomas et al. (2011) Thomas, R. C., Aldering, G., Antilogus, P., et al. 2011, ApJ, 743, 27, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/743/1/27

- Thöne et al. (2009) Thöne, C. C., Michałowski, M. J., Leloudas, G., et al. 2009, ApJ, 698, 1307, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/698/2/1307

- Tomasella et al. (2021) Tomasella, L., Benetti, S., Cappellaro, E., & Pastorello, A. 2021, Transient Name Server Classification Report, 2021-1031, 1

- Tsvetkov & Elenin (2010) Tsvetkov, D. Y., & Elenin, L. 2010, Peremennye Zvezdy, 30, 2. https://arxiv.org/abs/1003.2558

- Tsvetkov et al. (2013) Tsvetkov, D. Y., Shugarov, S. Y., Volkov, I. M., et al. 2013, Contributions of the Astronomical Observatory Skalnate Pleso, 43, 94. https://arxiv.org/abs/1311.3484

- Tully et al. (2013) Tully, R. B., Courtois, H. M., Dolphin, A. E., et al. 2013, AJ, 146, 86, doi: 10.1088/0004-6256/146/4/86

- van Dokkum (2001) van Dokkum, P. G. 2001, PASP, 113, 1420, doi: 10.1086/323894

- Virtanen et al. (2020) Virtanen, P., Gommers, R., Oliphant, T. E., et al. 2020, Nature Methods, 17, 261, doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2

- Wang et al. (2020) Wang, L., Contreras, C., Hu, M., et al. 2020, ApJ, 904, 14, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/abba82

- Wang et al. (2013) Wang, X., Wang, L., Filippenko, A. V., Zhang, T., & Zhao, X. 2013, Science, 340, 170, doi: 10.1126/science.1231502

- Wang et al. (2006) Wang, X., Wang, L., Pain, R., Zhou, X., & Li, Z. 2006, ApJ, 645, 488, doi: 10.1086/504312

- Wang et al. (2005) Wang, X., Wang, L., Zhou, X., Lou, Y.-Q., & Li, Z. 2005, ApJ, 620, L87, doi: 10.1086/428774

- Wang et al. (2009) Wang, X., Filippenko, A. V., Ganeshalingam, M., et al. 2009, ApJ, 699, L139, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/699/2/L139

- Webbink (1984) Webbink, R. F. 1984, ApJ, 277, 355, doi: 10.1086/161701

- Whelan & Iben (1973) Whelan, J., & Iben, Icko, J. 1973, ApJ, 186, 1007, doi: 10.1086/152565

- Wong et al. (2020) Wong, K. C., Suyu, S. H., Chen, G. C. F., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 498, 1420, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stz3094

- Wu et al. (1995) Wu, H., Yan, H. J., & Zou, Z. L. 1995, A&A, 294, L9

- Yang et al. (2020) Yang, Y., Hoeflich, P., Baade, D., et al. 2020, ApJ, 902, 46, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aba759

- Yaron & Gal-Yam (2012) Yaron, O., & Gal-Yam, A. 2012, PASP, 124, 668, doi: 10.1086/666656

- Zeng et al. (2021) Zeng, X., Wang, X., Esamdin, A., et al. 2021, ApJ, 919, 49, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ac0e9c

- Zhang et al. (2017) Zhang, B. R., Childress, M. J., Davis, T. M., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 471, 2254, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stx1600

| UT Date | MJD | phaseaaDays relative to the -band maximum (MJD = 59,321.862 0.450) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 April 03 | 59,307.521 | 14.368 | 180.0 | 17.791 | 0.056 | 180.0 | 17.252 | 0.041 | 180.0 | 17.206 | 0.038 | 180.0 | 17.045 | 0.062 |

| 2021 April 04 | 59,308.485 | 13.404 | 180.0 | 17.253 | 0.105 | 180.0 | 16.597 | 0.057 | 180.0 | 16.580 | 0.045 | 180.0 | 16.909 | 0.099 |

| 2021 April 07 | 59,311.569 | 10.320 | 200.0 | 15.397 | 0.016 | 200.0 | 15.294 | 0.015 | 200.0 | 15.321 | 0.013 | 200.0 | 15.338 | 0.017 |

| 2021 April 08 | 59,312.505 | 9.384 | 200.0 | 15.127 | 0.021 | 200.0 | 15.045 | 0.026 | 200.0 | 15.108 | 0.017 | 200.0 | 15.122 | 0.018 |

| 2021 April 09 | 59,313.559 | 8.330 | 200.0 | 14.832 | 0.059 | 200.0 | 14.870 | 0.040 | 200.0 | 14.871 | 0.024 | 200.0 | 14.859 | 0.022 |

| 2021 April 10 | 59,314.566 | 7.323 | 200.0 | 14.565 | 0.075 | 200.0 | 14.601 | 0.065 | 200.0 | 14.670 | 0.038 | 200.0 | 14.692 | 0.039 |

| 2021 April 13 | 59,317.508 | 4.381 | 200.0 | 14.352 | 0.012 | 200.0 | 14.365 | 0.014 | 200.0 | 14.379 | 0.014 | 200.0 | 14.500 | 0.015 |

| 2021 April 14 | 59,318.498 | 3.391 | 200.0 | 14.297 | 0.028 | 200.0 | 14.278 | 0.020 | 200.0 | 14.334 | 0.013 | 200.0 | 14.479 | 0.016 |

| 2021 April 18 | 59,322.506 | 0.617 | 200.0 | 14.202 | 0.030 | 200.0 | 14.167 | 0.022 | 200.0 | 14.185 | 0.015 | 200.0 | 14.487 | 0.018 |

| 2021 April 19 | 59,323.506 | 1.617 | 200.0 | 14.200 | 0.034 | 200.0 | 14.162 | 0.023 | 200.0 | 14.172 | 0.017 | 200.0 | 14.524 | 0.020 |

| 2021 April 20 | 59,324.493 | 2.604 | 200.0 | 14.263 | 0.117 | 200.0 | 14.141 | 0.057 | 200.0 | 14.180 | 0.043 | 200.0 | 14.558 | 0.035 |

| 2021 April 27 | 59,331.727 | 9.838 | – | – | – | 200.0 | 14.332 | 0.018 | 200.0 | 14.480 | 0.015 | 200.0 | 14.818 | 0.017 |

| 2021 April 30 | 59,334.509 | 12.620 | 200.0 | 14.925 | 0.017 | 200.0 | 14.560 | 0.021 | 200.0 | 14.700 | 0.013 | 200.0 | 14.950 | 0.017 |

| 2021 May 2 | 59,336.507 | 14.618 | 200.0 | 15.085 | 0.054 | 200.0 | 14.612 | 0.058 | 200.0 | 14.794 | 0.030 | 200.0 | 15.044 | 0.025 |

| 2021 May 5 | 59,339.511 | 17.622 | 200.0 | 15.412 | 0.039 | 200.0 | 14.873 | 0.027 | 200.0 | 14.920 | 0.016 | 200.0 | 14.939 | 0.020 |

| 2021 May 7 | 59,341.519 | 19.630 | 200.0 | 15.775 | 0.046 | 200.0 | 14.980 | 0.032 | 200.0 | 14.932 | 0.023 | 200.0 | 14.847 | 0.030 |

| 2021 May 8 | 59,342.521 | 20.632 | 200.0 | 15.831 | 0.023 | 200.0 | 15.016 | 0.014 | 200.0 | 14.934 | 0.011 | 200.0 | 14.840 | 0.013 |

| 2021 May 10 | 59,344.559 | 22.670 | 200.0 | 16.017 | 0.019 | 200.0 | 15.131 | 0.018 | 200.0 | 14.963 | 0.012 | 200.0 | 14.775 | 0.017 |

| 2021 May 11 | 59,345.528 | 23.639 | 200.0 | 16.132 | 0.043 | 200.0 | 15.196 | 0.024 | 200.0 | 14.991 | 0.017 | 200.0 | 14.760 | 0.026 |

| 2021 May 16 | 59,350.526 | 28.637 | 200.0 | 16.493 | 0.048 | 200.0 | 15.488 | 0.026 | 200.0 | 15.124 | 0.018 | 200.0 | 14.758 | 0.024 |

| 2021 May 17 | 59,351.522 | 29.633 | 200.0 | 16.699 | 0.084 | 200.0 | 15.543 | 0.030 | 200.0 | 15.195 | 0.025 | 200.0 | 14.747 | 0.020 |

| 2021 May 24 | 59,358.548 | 36.659 | 200.0 | 17.063 | 0.055 | 200.0 | 16.013 | 0.024 | 200.0 | 15.658 | 0.021 | 200.0 | 15.230 | 0.023 |

| 2021 May 25 | 59,359.550 | 37.661 | – | – | – | 200.0 | 16.030 | 0.042 | 200.0 | 15.690 | 0.032 | 200.0 | 15.289 | 0.032 |

| 2021 May 30 | 59,364.597 | 42.708 | 200.0 | 17.361 | 0.034 | 200.0 | 16.267 | 0.014 | 200.0 | 15.954 | 0.013 | 200.0 | 15.605 | 0.019 |

| 2021 June 2 | 59,367.589 | 45.700 | 200.0 | 17.399 | 0.029 | 200.0 | 16.332 | 0.015 | 200.0 | 16.021 | 0.013 | 200.0 | 15.727 | 0.017 |

| 2021 June 3 | 59,368.557 | 46.668 | – | – | – | 200.0 | 16.397 | 0.018 | 200.0 | 16.060 | 0.015 | 200.0 | 15.752 | 0.021 |

| UT Date | MJD | PhaseaaDays relative to the -band maximum (MJD = 59321.862 0.450) | Range | Resolution | Airmass | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| days | ||||||

| April 03, 2021 | 59307.517 | 14.372 | 3700-8800 | 20 | 3 1100.0 | 1.200 |

| April 13, 2021 | 59317.584 | 4.305 | 3700-8800 | 20 | 3 1200.0 | 1.209 |

| May 01, 2021 | 59335.501 | 13.612 | 3700-8800 | 20 | 3 1200.0 | 1.193 |

| May 10, 2021 | 59344.536 | 22.647 | 3700-8800 | 20 | 3 1200.0 | 1.231 |

| June 03, 2021 | 59368.581 | 46.692 | 3700-8800 | 20 | 3 1200.0 | 1.427 |

| June 20, 2021 | 59385.565 | 63.676 | 3700-8800 | 20 | 3 1200.0 | 1.515 |

| Band | ||

|---|---|---|

| mag | ||

| 59,321.862 0.450 | 14.017 0.017 | |

| 59,323.220 0.733 | 14.091 0.014 | |

| 59,323.522 0.537 | 14.123 0.009 | |

| 59,320.327 0.504 | 14.415 0.010 |

| Name | Type | R.A.(J2000) | Decl.(J2000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SN 1972H | SN Ia | 10:17:00.400 | +73:24:39.00 |

| SN 1997bq | SN Ia | 10:17:05.330 | +73:23:02.11 |

| SN 2006gi | SN Ib | 10:16:46.759 | +73:26:26.41 |

| SN 2008fv | SN Ia | 10:16:57.281 | +73:24:36.40 |

| SN 2021do | SN Ic | 10:16:56.522 | +73:23:50.93 |

| SN 2021hpr | SN Ia | 10:16:38.680 | +73:24:01.80 |

| Parameter | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| RA | 10:16:38.680 | 1 |

| Dec | +73:24:01.80 | 1 |

| Type | SN Ia | 1,3 |

| Host galaxy | NGC 3147 | 1 |

| Discoverer | Koichi Itagaki | 1 |

| Discovery Date | 2021 04 02 10:46:28.000 | 1 |

| Discovery MagaaUnfiltered | 17.7 mag | 1 |

| redshift | 0.009346 | 1 |

| Distance | 46.02 3.23 Mpc | 3 |

| Distance modulus | 33.46 0.21 mag | 3 |

| 0.0208 mag | 2 | |

| 0.088 mag | 2 | |

| 0.067 mag | 2 | |

| 0.053 mag | 2 | |

| 0.037 mag | 2 | |

| 3 | ||

| mag | 3 | |

| mag | 3 | |

| bbDerived by SNooPy (Burns et al., 2011, 2014) | mag | 3 |

| 3 | ||

| d | 3 |