On extropy of past lifetime distribution

Abstract

Recently Qiu et al. (2017) have introduced residual extropy as measure of uncertainty in residual lifetime distributions analogues to residual entropy (1996). Also, they obtained some properties and applications of that. In this paper, we study the extropy to measure the uncertainty in a past lifetime distribution. This measure of uncertainty is called past extropy. Also it is showed a characterization result about the past extropy of largest order statistics.

Keywords: Reversed residual lifetime, Past extropy, Characterization, Order statistics.

AMS Subject Classification: 94A17, 62B10, 62G30

1 Introduction

The concept of Shannon entropy as a seminal measure of uncertainty for a random variable was proposed by Shannon (1948). Shannon entropy for a non-negative and absolutely continuous random variable is defined as follows:

| (1) |

where F and f are cumulative distribution function (CDF) and probability density function (pdf), respectively. There are huge literatures devoted to the applications, generalizations and properties of Shannon entropy (see, e.g. Cover and Thomas, 2006).

Recently, a new measure of uncertainty was proposed by Lad et al. (2015) called extyopy as a complement dual of Shannon entropy (1948). For a non-negative random variable the extropy is defined as below:

| (2) |

It’s obvious that

One of the statistical applications of extropy is to score the forecasting distributions using the total log scoring rule.

Study of duration is an interest subject in many fields of science such as reliability, survival analysis, and forensic science. In these areas, the additional life time given that the component or system or a living organism has survived up to time is termed the residual life function of the component. If is the life of a component, then is called the residual life function. If a component is known to have survived to age then extropy is no longer useful to measure the uncertainty of remaining lifetime of the component.

Therefore, Ebrahimi (1996) defined the entropy for resudial lifetime as a dynamic form of uncertainty called the residual entropy at time and defined as

where is the survival (reliability) funltion of .

Analogous to residual entropy, Qiu et al. (2017) defined the extropy for residual lifetime called the residual extropy at time and defined as

| (3) |

In many situations, uncertainty can relate to the past. Suppose the random variable is the lifetime of a component, system or a living organism, having an absolutely continuous distribution function and the density function . For , let the random variable be the time elapsed after failure till time , given that the component has already failed at time . We denote the random variable , the reversed residual life (past lifetime). For instance, at time , one has under gone a medical test to check for a certain disease. Suppose that the test result is positive. If is the age when the patient was infected, then it is known that . Now the question is, how much time has elapsed since the patient has been infected by this disease? Based on this idea, Di Crescenzo and Longobardi (2002) introduced the entropy of the reversed residual lifetime as a dynamic measure of uncertainty called past entropy as follows:

This measure is dual of residual entropy introduced by Ebrahimi (1996).

In this paper, we study the extropy for as dual of residual extropy that is called past extropy and it is defined as below (see also Krishnan et al. (2020)):

| (4) |

where , for . It can be seen that for , possesses all the properties of .

Remark 1.

It’s clear that .

Past extropy has applications in the context of information theory, reliability and survival analysis, insurance, forensic science and other related fields beceuse in that a lifetime distribution truncated above is of utmost importance.

The paper is organized as follows: in section 2, an approach to measure of uncertainty in the past lifetime distribution is proposed. Then it is studied a characterization result with the reversed failure rate. Following a characterization result is given based on past extropy of the largest order statistics in section 3.

2 Past extropy and some characterizations

Analogous to residual extropy (Qiu et al. (2017)), the extropy for is called past extropy and for a non-negative random variable is as below:

| (5) |

where , for is the density function of . It’s clear that while the residual entropy of a continuous distribution may take any value on . Also, .

Example 1.

-

a)

If , then for . This shows that the past extropy of exponential distribution is an increasing function of t.

-

b)

If , then .

-

c)

If has power distribution with parameter , i.e. , , then .

-

d)

If has Pareto distribution with parameters , i.e. , , then .

There is a functional relation between past extropy and residual extropy as follows:

In fact

From (4) we can rewrite the following expression for the past extropy:

where is the reversed failure rate.

Definition 1.

A random variable is said to be increasing (decreasing) in past extropy if is an increasing (decreasing) function of .

Theorem 2.1.

is increasing (decreasing) if and only if .

Proof.

Theorem 2.2.

The past extropy of is uniquely determined by .

Proof.

From (5) we get

So we have a linear differential equation of order one and it can be solved in the following way

where we can use the boundary condition , so we get

| (6) |

∎

Example 2.

Using the following definition (see Shaked and Shanthikumar, 2007), we show that is increasing in .

Definition 2.

Let and be two non-negative variables with reliability functions and pdfs respectively. is smaller than

-

a)

in the likelihood ratio order, denoted by , if is decreasing in ;

-

b)

in the usual stochastic order, denoted by if for .

Remark 2.

It is well known that if then and if and only if for any decreasing (increasing) function .

Theorem 2.3.

Let be a random variable with CDF and pdf . If is decreasing in , then is increasing in .

Proof.

Let be a random variable with uniform distribution on with pdf for , then based on (4) we have

Let . If , then is a non-negative constant. If , then . Therefore is decreasing in , which implies . Hence and so

using the assumption that is a decreasing function. Since then

∎

Remark 3.

Let be a random variable with CDF , for . Then is increasing in . However is increasing in . So the condition in theorem 2.3 that is decreasing in is sufficient but not necessary.

3 Past extropy of order statistics

Let be a random sample with distribution function , the order statistics of the sample are defined by the arrangement from the minimum to the maximum by . Qiu and Jia (2017) defined the residual extropy of the order statistics and showed that the residual extropy of order statistics can determine the underlying distribution uniquely. Let be continuous and i.i.d. random variables with CDF indicate the lifetimes of components of a parallel system. Also be the ordered lifetimes of the components. Then represents the lifetime of parallel system with CDF , . The CDF of is where is called reversed residual lifetime of the system. Now past extropy for reversed residual lifetime of parallel system with distribution function is as follows:

Theorem 3.1.

If has an increasing pdf on , with , then is decreasing in .

Proof.

The pdf of can be expressed as

We note that

is decreasing in and so which implies . If is increasing on we have

From the definition of the past extropy it follows that

Then it follows that

Since the past extropy of a random variable is non-negative we have and the proof is completed. ∎

Example 3.

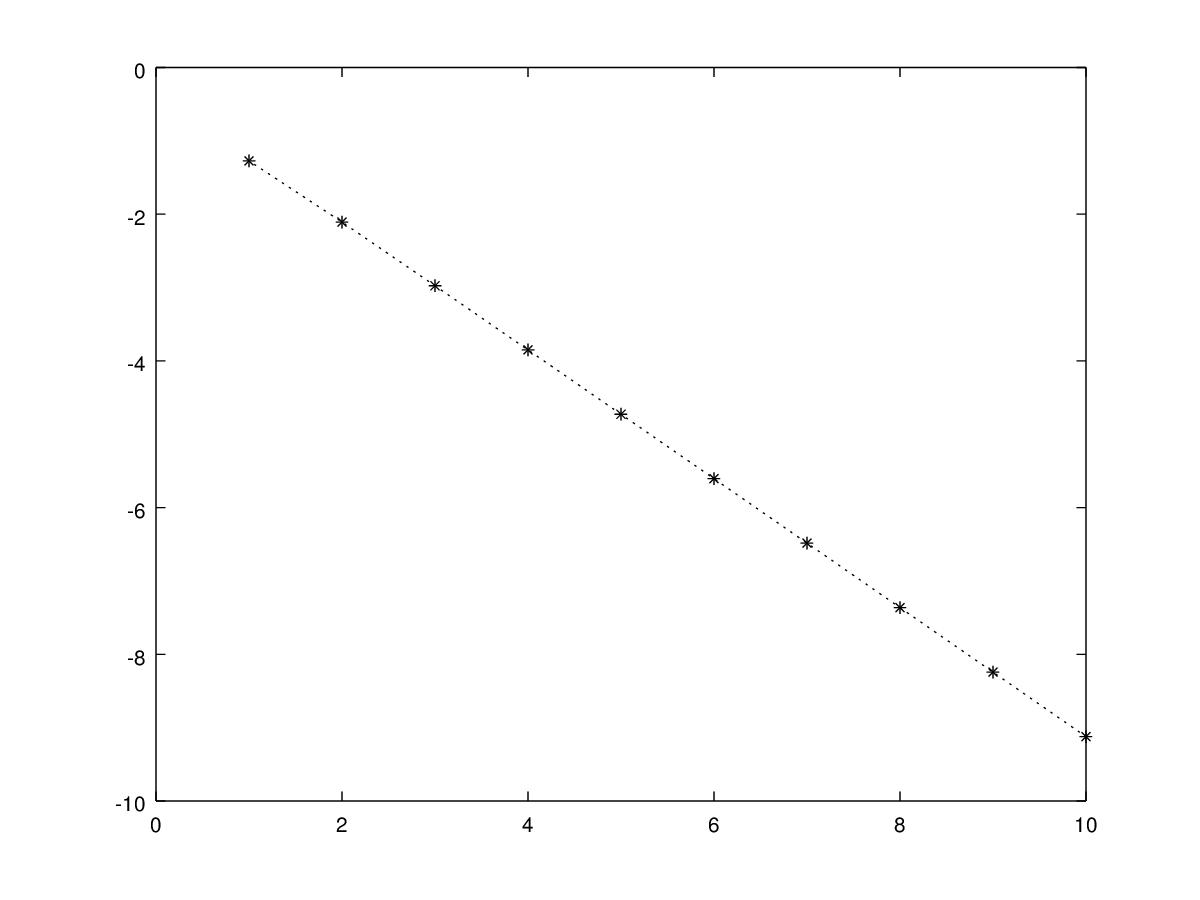

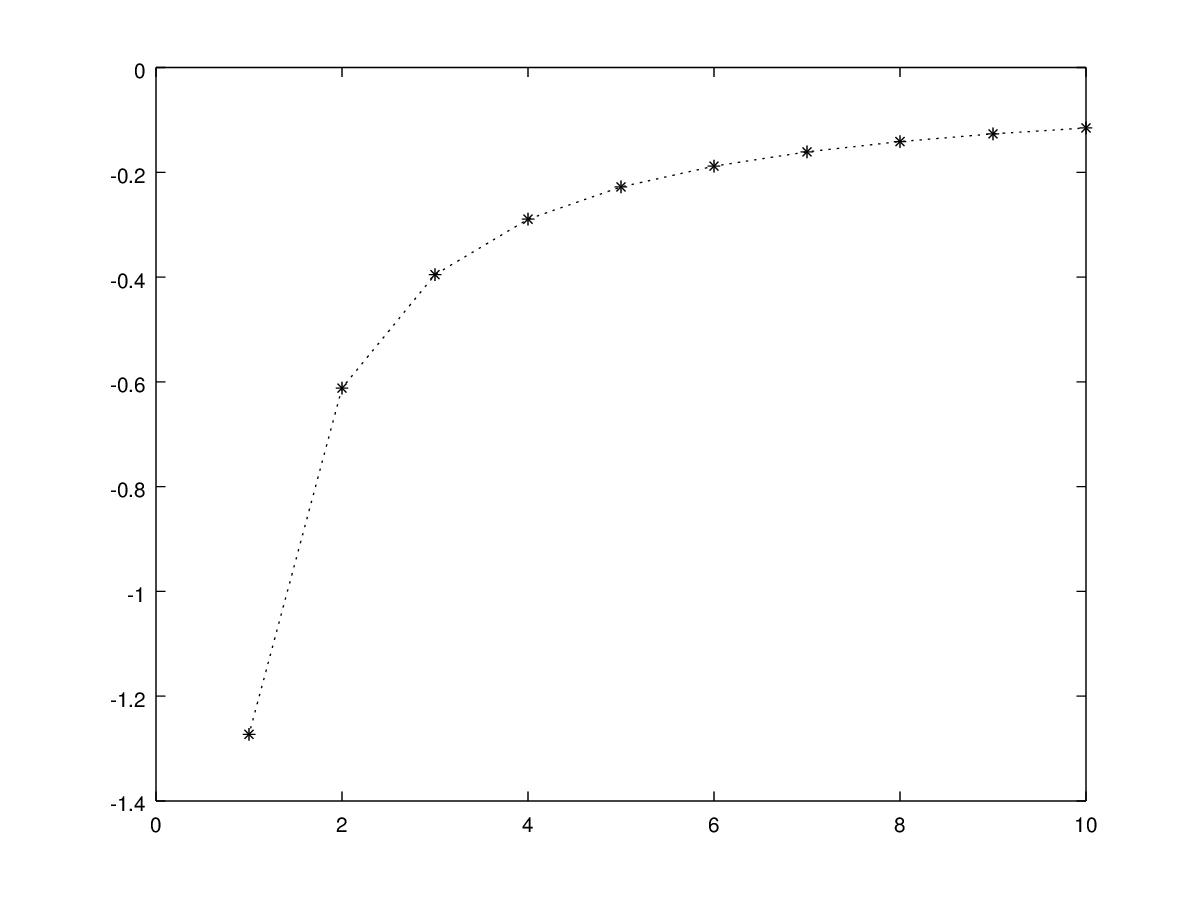

Let be a random variable distribuited as a Weibull with two parameters, , i.e. . It can be showed that for this pdf has a maximum point . Let us consider the case in which has a Weibull distribution with parameters and , and so . The hypothesis of the theorem 3.1 are satisfied for . Figure 1 shows that is decreasing in . Moreover the result of the theorem 3.1 does not hold for the smallest order statistic as shown in figure 2.

In the case in which has an increasing pdf on with we give a lower bound for .

Theorem 3.2.

If has an increasing pdf on , with , then .

Proof.

From the definition we get

∎

Example 4.

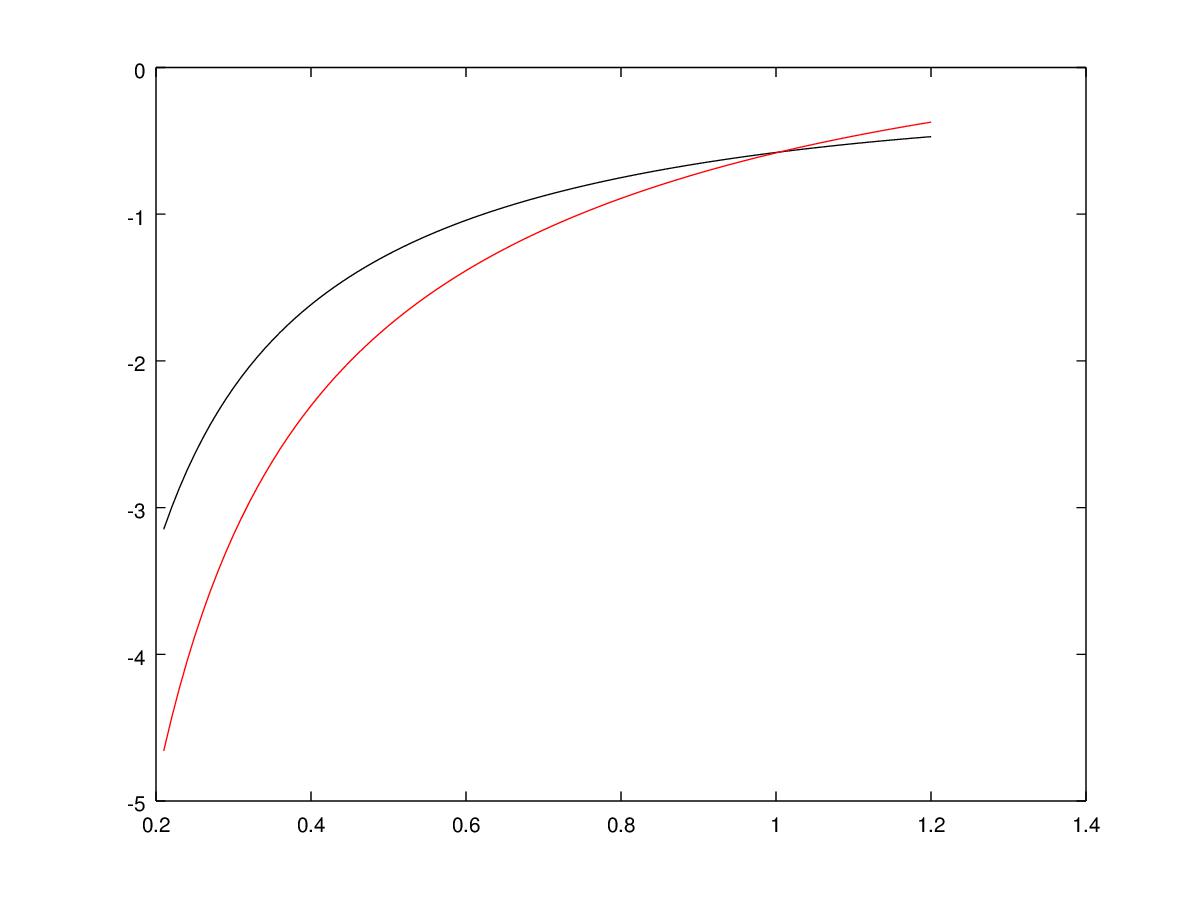

Let , as in example 3, so we know that its pdf is increasing in with . The hypothesis of the theorem 3.2 are satisfied for . Figure 3 shows that the function (in red) is a lower bound for the past extropy (in black). We remark that the theorem gives information only for , in fact for larger values of the function could not be a lower bound anymore, as showed in figure 3.

Qiu (2016), Qiu and Jia (2017) showed that extropy of the order statistics and residual extropy of the order statistics can characterize the underlying distribution uniquely. In the following theorem, whose proof requires next lemma, we show that the past extropy of the largest order statistic can uniquely characterize the underlying distribution.

Lemma 3.1.

Let and be non-negative random variables such that , . Then .

Proof.

From the definition of the extropy, holds if and only if

i.e. if and only if

Putting in the left side of the above equation and in the right side we have

that is equivalent to

Then from Lemma 3.1 of Qui (2017) we get for all . By taking we have and so for all . This is equivalent to i.e. , for all with constant. But for we have and so . ∎

Theorem 3.3.

Let and be two non-negative random variables with cumulative distribution functions and , respectively. Then and belong to the same family of distributions if and only if for , ,

Proof.

It sufficies to prove the sufficiency. is the past extropy for but it is also the extropy for the variable . So through lemma 3.1 we get . Then , for . If exists such that then in with . But for all , exists such that and so and as in the precedent step we have for . Letting to we have a contradiction because and are both distribution function and their limit is 1. ∎

4 Conclusion

In this paper we studied a measure of uncertainty, the past extropy. It is the extropy of the inactivity time. It is important in the moment in which with an observation we find our system down and we want to investigate about how much time has elapsed after its fail. Moreover we studied some connections with the largest order statistic.

5 Acknowledgement

Francesco Buono is partially supported by the GNAMPA research group of INdAM (Istituto Nazionale di Alta Matematica) and MIUR-PRIN 2017, Project ”Stochastic Models for Complex Systems” (No. 2017 JFFHSH).

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- [1] Cover, T. M. and Thomas, J. A., 2006. Elements of Information Theory, (2nd edn). Wiley, New York.

- [2] Di Crescenzo, A., Longobardi, M., 2002. Entropy-based measure of uncertainty in past lifetime distributions, Journal of Applied Probability, 39, 434–440.

- [3] Ebrahimi, N., 1996. How to measure uncertainty in the residual life time distribution. Sankhya: The Indian Journal of Statistics, Series A, 58, 48–56.

- [4] Krishnan, A. S., Sunoj S. M., Nair N. U., 2020. Some reliability properties of extropy for residual and past lifetime random variables. Journal of the Korean Statistical Society. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42952-019-00023-x.

- [5] Lad, F., Sanfilippo, G., Agrò, G., 2015. Extropy: complementary dual of entropy. Statistical Science 30, 40–58.

- [6] Qiu, G., 2017. The extropy of order statistics and record values. Statistics & Probability Letters, 120, 52–60.

- [7] Qiu, G., Jia, K., 2018. The residual extropy of order statistics. Statistics & Probability Letters, 133, 15–22.

- [8] Shaked, M., Shanthikumar, J. G., 2007. Stochastic orders. Springer Science & Business Media.

- [9] Shannon, C. E., 1948. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27, 379–423.