New Relativistic Theory for Modified Newtonian Dynamics

Abstract

We propose a relativistic gravitational theory leading to modified Newtonian dynamics, a paradigm that explains the observed universal galactic acceleration scale and related phenomenology. We discuss phenomenological requirements leading to its construction and demonstrate its agreement with the observed cosmic microwave background and matter power spectra on linear cosmological scales. We show that its action expanded to second order is free of ghost instabilities and discuss its possible embedding in a more fundamental theory.

Introduction. –

Alternative theories of gravity to general relativity (GR) have received immense interest in the past 20 years or so [1, 2]. The driving force behind this interest is not so much that gravity has not been tested in a large region of parameter space [3], but, more importantly, the cosmological systems residing in some parts of that region exhibit behavior from which dark matter (DM) and dark energy (DE), collectively called the dark sector, are inferred.

While most investigations deal with DE, the hypothesis that the DM phenomenon is due to gravitational degrees of freedom (d.o.f.) has received less attention [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Earliest evidence for the existence of DM [15, 16, 17] was later supported by observations of the motion of stars within galaxies [18, 19]. Milgrom proposed [20, 21, 22] that this could, instead, result from modifying the inertia or dynamics of baryons or the gravitational law at accelerations smaller than . The latter is further explored in [23] where if gradients of the potential are smaller than , nonrelativistic gravity is effectively governed by

| (1) |

Here, is the Newtonian gravitational constant, and the matter density. These models are referred to as modified Newtonian dynamics (MOND).

Much work has gone into deducing astrophysical consequences of MOND, its consistency with data [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46], and alternative DM based explanations of this law [47, 48, 49, 50] It is inherently nonrelativistic and, thus, difficult to test in cosmological settings (but see [51]) as systems such as the cosmic microwave background (CMB) require a relativistic treatment. CMB physics involves only linearly perturbing a Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) background, making it a particularly useful system, devoid of nonlinear modeling systematics, for testing relativistic MOND (RMOND). Relativistic theories that yield MOND behavior have been proposed [23, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67] making clear predictions regarding gravitational lensing and cosmology. In cases where the CMB and matter power spectra (MPS) have been computed, no theory has been shown to fit all of the cosmological data while preserving MOND phenomenology in galaxies [68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76], (though see [77]).

We present the first RMOND theory which reproduces galactic and lensing phenomenology similar to the Bekenstein-Sanders Tensor-Vector-Scalar (TeVeS) theory [53, 54] and, unlike TeVeS, successfully reproduces the key cosmological observables: CMB and MPS. We describe its construction, discuss its cosmology and show that it is devoid of ghost instabilities. We discuss open questions and possibilities toward its more fundamental grounding.

Phenomenological requirements. –

RMOND theories have always been constructed on phenomenological grounds rather than based on fundamental principles. Quite likely the reason is that the MOND law is empirical, and even the observation that it is scale invariant [78, 79] has not yet led to a definitive conclusion as to how this invariance could lead to a MOND gravitational theory. RMOND theories should obey the principle of general covariance and the Einstein equivalence principle. These are, however, do not provide any guidance as to how RMOND should look like. Indeed, many theories obeying these have nothing to do with MOND, and many RMOND theories obeying these same principles are in conflict with observations. Principle-based MOND theories include [80, 81, 82], however, these are nonrelativistic. Still, the phenomenological approach, that we also follow, can provide valuable guidance toward a more fundamental theory.

What are the necessary phenomenological facts that any successful MOND theory should lead to? It must (i) return to GR (hence, Newtonian gravity) when in quasistatic situations while (ii) reproducing the MOND law (1) when . It should also (iii) be in harmony with cosmological observations including the CMB and MPS, (iv) reproduce the observed gravitational lensing of isolated objects without DM halos, and (v) propagate tensor mode gravitational waves (GWs) at the speed of light.

We consider each requirement in turn. Clearly, (i) means that when , the standard Poisson equation holds while (ii) means that when the MOND equation (1) holds. While in many cases [60, 61, 56] the transition between (i) and (ii) depends only on , in TeVeS it is facilitated by a scalar d.o.f. . We follow the latter and assume that the physics encapsulated by (i) and (ii) fits within the TeVeS framework.

A template nonrelativistic action then, is

| (2) |

where is the potential that couples universally to matter, is a constant and . The field obeys while obeys the Poisson equation . Emergence of MOND is then ensured if as . It is in this limit that appears.

For a point source of mass , the MOND-to-Newton transition occurs at . A MOND force lends its way trivially to a Newtonian force as but in the inner Solar System this is not sufficient. Corrections to due to will compete with the post-Newtonian force , and these are constrained at Mercury’s orbit to less than [83, 84]. Suppressing these may happen either through screening or tracking. In the former, is screened at large so that while in the latter , so that . We model both with since screening is equivalent to . In terms of , tracking happens if , while screening occurs if has terms with (this may be in conflict with Mercury’s orbit even as ) or via higher-derivative terms absent from (2).

Consider requirement (iii), that is, successful cosmology. In (2) we have a new d.o.f. and we expect that the same will appear in cosmology, albeit with a time dependence, i.e. . Consider a flat FLRW metric so that and where is the lapse function and the scale factor. What should the expectation for a cosmological evolution of be? The MOND law for galaxies is silent regarding this matter. There is, however, another empirical law which concerns cosmology: the existence of sizable amounts of energy density scaling precisely as . Within the DM paradigm such a law is a natural consequence of particles obeying the collisionless Boltzmann equation. The validity of this law has been tested [85, 86] and during the time between radiation-matter equality and recombination it is valid within an accuracy of . Do scalar field models leading to energy density scaling as exist?

The answer is yes: shift symmetric essence. It has been shown [87] that a scalar field with Lagrangian where , leads to dust (i.e. ) plus cosmological constant (CC) solutions provided has a minimum at . Such a model is the low energy limit of ghost condensation [88, 89] although the latter also contains higher derivative terms in its action. The FLRW action is

| (3) |

where and . Interestingly, (2) and (3) are shift symmetric in and respectively.

We propose that the MOND analog on FLRW is given by (3) with

| (4) |

where is the CC, and parameters and denote higher powers in this expansion. Expanding in rather than is the most general expansion leading to dust solutions and includes the case. The CC in this model remains a freely specifiable parameter, just as in the -cold dark matter (CDM) model. Following [88, 89], we call this the (gravitational) Higgs phase.

Requirement (iv), that is, correct gravitational lensing without DM, requires a relativistic theory. A minimal theory for RMOND is a scalar-tensor theory[23] with the scalar providing for a conformal factor between two metrics. However, since null geodesics are unaltered by conformal transformations, such theories cannot produce enough lensing from baryons in the MOND regime. Sanders solved the lensing problem by changing the conformal into a disformal transformation [53] using a unit-timelike vector field, incorporated by Bekenstein [54] into TeVeS. The unit-timelike vector has component and this ensures that the two metric potentials are equal (as in GR), so that solutions which mimic DM also produce the correct light deflection.

Meanwhile the anisotropic scaling of the MOND law compared with a well-behaved cosmology implying terms like and , heuristically implies (gravitational) Lorentz violation. A good way of introducing such an ingredient is via a unit-timelike vector field , much like the spirit of the Einstein-Æther theory [90, 91], and TeVeS [53, 54].

The advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational Observatory (LIGO) and Virgo interferometers [92] observed GWs from a binary neutron star merger. Combined with electromagnetic observations [93, 94], this strongly constrains the GW tensor mode speed to be effectively equal to that of light. By analyzing the tensor mode speed, TeVeS has been shown [95, 96, 97, 98] to be incompatible with the LIGO-Virgo observations for any choice of parameters. The necessary d.o.f. and are also ingredients of TeVeS, only there, a second metric was introduced as a combination of , and . In [99], and were combined into a timelike (but not unit) vector , and it was shown that TeVeS may be equivalently formulated with a single metric minimally coupled to matter, and with a noncanonical and rather complicated kinetic term. A general class of theories based on the pair was uncovered [98] where the tensor mode speed equals the speed of light in all situations, satisfying requirement (v).

The new theory. –

A subset of the general class [98] depends on a scalar and unit-timelike vector such that [100]

| (5) |

where , , and the Lagrange multiplier imposes the unit-timelike constraint on . In addition is a free function of and where is the three-metric orthogonal to . Notice that (5) is shift symmetric under .

On FLRW while and , hence and . We define so that (5) turns precisely into (3), which we have argued that it satisfies requirement (iii).

In the weak-field quasistatic limit, we set and and assume that aligns with the time direction so that and . The scalar is expanded as with and may be set to its (late Universe) FLRW minimum . Hence, . Then (5) leads to which can be subbed back to get

| (6) |

where . Compared with (2) a new term appears which looks like a “mass term” for , with . The solution for will be as obtained from (2) only for where , and oscillatory for . We require so that MOND behavior according to (2) may still be attained in galaxies. Thus, the quasistatic limit has at least three parameters: , and .

While matter couples only to , gravity comes with two potentials and whose action is not diagonal but contains the mixing term . Without the latter, decouples and no modification of gravity arises in this situation, apart from which is akin to ghost condensation [88, 89]. Diagonalizing by setting and identifying turns (6) into (2) (plus the term). Since, , (6) leads to the right lensing whenever the solution for mimics DM. This satisfies requirements (i), (ii) and (iv).

Cosmological observables. –

The theory just presented was constructed to lead to a FLRW universe resembling CDM. Given a general , we define the energy density as and pressure as so that the usual FLRW equations are satisfied. The field equation for may be integrated once to give for initial condition . When obeys the expansion (4), then , so that , where . The pressure is where is the equation of state at , that is, so that . A time-varying implies an adiabatic sound speed and if obeys (4) then . Clearly, and , where the zero point is reached as . As the solution depends on the initial condition , the density is not (classically) predicted.

For a proper cosmological matter era in the Higgs phase we need to be sufficiently small. Observations [85, 86] give at , hence, . Meanwhile, in order not to spoil the MOND behavior, leading to . Unless the effect of the term in (6) is alleviated in some future theory, the Higgs phase cannot be extended too long in the past, and higher terms in (4) must be taken into consideration. Within the present setup, one can arrange this with a function which suppresses and during most of the cosmic evolution. Examples are (“Cosh function”) and (“Exp function”) where .

The tight coupling of baryons to photons in the early Universe leads to Silk damping and wipes out all small-scale structure in baryons, preventing the formation of galaxies in the late Universe. Within GR, cold DM sustains the gravitational potentials during the tight coupling period, driving the formation of galaxies and affecting the relative peak heights of the CMB as further corroborated by e.g. the Planck satellite [101]. Checking whether this theory fits the CMB and MPS spectra requires studying linear fluctuations on FLRW.

We consider scalar modes in the Newtonian gauge so that , and and perturb the scalar as and the vector as . The perturbed Einstein, vector and scalar equations, then depend on the new scalar modes and and their derivatives. The shear equation remains as in GR, as do the usual perturbed Boltzmann equations for baryon, photons and neutrinos, since they couple only to .

Setting , , and defining the density contrast and momentum divergence via

| (7) | ||||

| (8) |

the Einstein equations take the same form as in GR, i.e. and where the index runs over all matter species including the new variables and . These obey standard fluid equations

| (9) | ||||

| (10) |

but with nonstandard pressure contrast:

| (11) |

Hence, the resulting system is not equivalent to a dark fluid: the nonstandard pressure, thus defined, does not close under the fluid variables but, rather, depends on the vector field perturbations and . The latter evolves with

| (12) |

Cosmologically, the necessary additional free parameters to CDM are (influencing the effective cosmological gravitational strength), , (or equivalently ) and . These fix appearing in the quasistatic regime. More elaborate functions introduce further parameters, e.g. in the case of the “Cosh” or “Exp” functions above. Note that does not appear in the linear cosmological regime but will play a role once nonlinear terms from kick in.

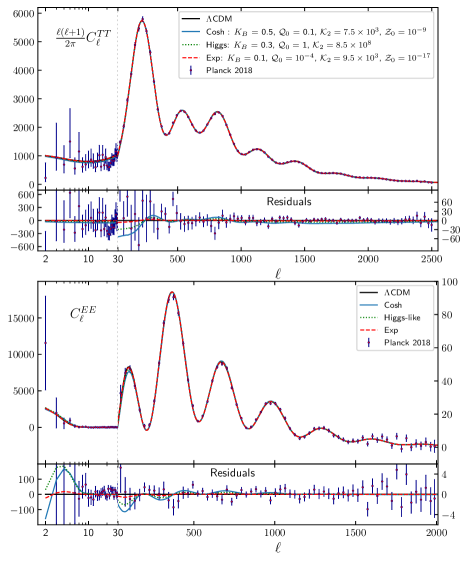

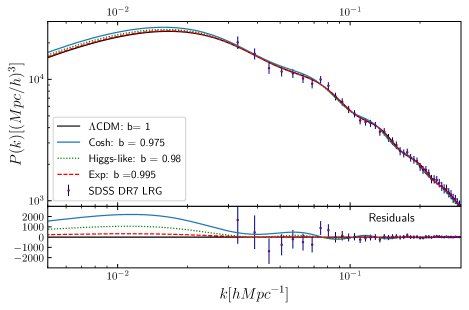

In Figs. 1 and 2 we show the CMB and MPS in the case of a “Cosh”, an “Exp” and a “Higgs-like” function , computed numerically by evolving the FLRW background and linearized equations using our own Boltzmann code [102], which is in excellent agreement with other codes, see [103] for a comparison. We have used adiabatic initial conditions [104] and a standard initial power spectrum with amplitude and spectral index . The MPS has an additional bias parameter . We used RECFAST version 1.5 for modeling recombination and have boosted sampling, time sampling and sampling accuracy for ensuring robust results. The detailed cosmology and the dependence of the spectra on the parameters will be investigated elsewhere [104]. For a wide range of parameters, this relativistic MOND theory is consistent with the CMB measurements from Planck. This happens because and are small enough so that and we get dustlike evolution as and , while the vector field decouples.

Stability and waves. –

Now, we consider stability of the theory on Minkowski spacetime. We expand , split and let with , and being small perturbations. Expanding (5) to second order gives

| (13) |

where we have used the desired late Universe limit for which and . We set as a free parameter which is zero in the MOND limit but nonzero in the GR limit when reached by tracking. Inspecting (13), the tensor mode action is as in GR as expected.

For vector modes we choose the gauge , and while and where and are transverse. Setting all modes , the dispersion relation for is where their mass is , hence, they are healthy if and . They decouple from and are not expected to be generated to leading order by compact objects.

Considering scalar modes in the Newtonian gauge we set , and while and find the dispersion relations and . Thus, we require that in addition to the vector stability conditions. Only two normal modes exist implying the presence of constraints. These are revealed through a Hamiltonian analysis which also shows that these conditions lead to a positive Hamiltonian [106, 107] for the modes. The case leads to a constant mode with zero Hamiltonian but, also, to a mode varying linearly with . The Hamiltonian for the latter is positive for momenta larger than and otherwise negative, also requiring that . Such instabilities are likely akin to Jeans-type instabilities and do not cause quantum vacuum instability at low momenta [108].

Discussion. –

MOND has enjoyed success in fitting galactic rotation curves [24, 25, 27, 29, 44] and reproducing the baryonic Tully-Fisher relation [31, 33, 45]. The radial acceleration relation (RAR) [41] finds a comfortable interpretation within MOND. Studies of MOND with galaxy clusters [30, 109, 110, 38, 111, 112] report that either is larger in clusters and/or an additional dark component is necessary even when the MOND prescription is used. These studies, however, use the classic modified-inertia MOND while the theory presented here has additional features warranting its separate testing with clusters. We note that a RAR for clusters was reported [112], similar to the galaxy one albeit with a factor of 10 higher. MOND has been tested with dwarf spheroidal galaxies where discrepancies for some [26] were later dismissed with improved data [28, 113, 114, 115, 116]. There, good agreement was reported, except for Draco and Carina where the fits are quite poor [26, 114, 116, 117]. It is argued [113] that those two might be systems not in equilibrium. The global stability of M33 has been tested [118] with positive results while wide-binary data do not yet yield a decisive test [119].

We have shown how the cosmological regime of this theory reproduces the CMB and MPS power spectra on linear scales and that MOND-like behavior emerges in the quasistatic approximation. The latter is expected to hold for virialized objects, however, how such objects emerge from the underlying density field, i.e. how the two regimes connect, is an open problem. This will happen at a scale which is expected to depend on , and and quite likely the nonlinear term coming from will play a role. It is reasonable to expect that on mildly nonlinear scales, the quasistatic regime is not yet reached.

We remark that also contains a pure vector mode perturbation which is expected to behave similarly as in the Einstein-Æther theory [90, 91]. This may lead to imprints on the -mode CMB polarization signal [120].

Setting and canonically normalizing as in (4), the FLRW action (3) becomes

| (14) |

where . Considering the MOND limit in (5) gives where . This scale is indicative of the energy scale above which quantum corrections may be important and below which we can trust the classical theory. Since then . Newton’s law has been tested down to [121] and the curves in Figs.1 and 2 have .

Absence of ghosts to quadratic order signifies a healthy theory that could arise as a limit of a more fundamental theory. We do not have such a theory at present but we discuss a case that may bring us closer. The vector in (5) does not seem to obey gauge invariance but in the quadratic action (13) it does so through mixing with diffeomorphisms of . This is not an accident. Let us normalize via for some scale and insert the term . Varying with and using the constraint to eliminate from the action, perform a Stückelberg transformation and define the covariant derivative acting on “angular field” as . The action turns to plus -dependent terms, where , . The resulting action is that of the gauged ghost condensate (GGC) [122] or bumblebee field [123, 124] which has been proposed as a healthy gauge-invariant theory of spontaneous Lorentz violation. The Einstein-Æther theory, part of (5), is the (healthy) decoupling limit of GGC by taking if (in our notation) [122]. It is argued [122] that can be as high as .

Given that is shift symmetric it is natural to charge it under this symmetry similar to letting . Interestingly, we may identify while the term , both multiplied by appropriate constants. The terms involving may be constructed using . Although extending our work as such does not explain the MOND term , it may provide promising directions for further improvements.

Acknowledgements.

Acknowledgments We thank C. Burrage, P. Creminelli, S. Ilic, E. Kiritsis, M. Kopp, M. Milgrom, A. Padilla, R. Sanders and I. Sawicki for discussions. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) / ERC Grant Agreement No. 617656 “Theories and Models of the Dark Sector: Dark Matter, Dark Energy and Gravity” and from the European Structural and Investment Funds and the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MSMT) (Project CoGraDS - CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/15003/0000437).References

- Jain and Khoury [2010] B. Jain and J. Khoury, Annals Phys. 325, 1479 (2010), eprint arXiv:1004.3294.

- Clifton et al. [2012] T. Clifton, P. G. Ferreira, A. Padilla, and C. Skordis, Phys. Rept. 513, 1 (2012), eprint arXiv:1106.2476.

- Baker et al. [2015] T. Baker, D. Psaltis, and C. Skordis, Astrophys. J. 802, 63 (2015), eprint arXiv:1412.3455.

- Cembranos [2009] J. A. R. Cembranos, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 141301 (2009), eprint arXiv:0809.1653.

- Chamseddine and Mukhanov [2013] A. H. Chamseddine and V. Mukhanov, JHEP 11, 135 (2013), eprint arXiv:1308.5410.

- Arroja et al. [2016] F. Arroja, N. Bartolo, P. Karmakar, and S. Matarrese, JCAP 04, 042 (2016), eprint arXiv:1512.09374.

- Sebastiani et al. [2017] L. Sebastiani, S. Vagnozzi, and R. Myrzakulov, Adv. High Energy Phys. 2017, 3156915 (2017), eprint arXiv:1612.08661.

- Casalino et al. [2018] A. Casalino, M. Rinaldi, L. Sebastiani, and S. Vagnozzi, Phys. Dark Univ. 22, 108 (2018), eprint arXiv:1803.02620.

- Bettoni et al. [2014] D. Bettoni, M. Colombo, and S. Liberati, JCAP 02, 004 (2014), eprint arXiv:1310.3753.

- Mendoza et al. [2012] S. Mendoza, T. Bernal, J. C. Hidalgo, and S. Capozziello, AIP Conf. Proc. 1458, 483 (2012), eprint arXiv:1202.3629.

- Rinaldi [2017] M. Rinaldi, Phys. Dark Univ. 16, 14 (2017), eprint arXiv:1608.03839.

- Koutsoumbas et al. [2018] G. Koutsoumbas, K. Ntrekis, E. Papantonopoulos, and E. N. Saridakis, JCAP 02, 003 (2018), eprint arXiv:1704.08640.

- Diez-Tejedor et al. [2018a] A. Diez-Tejedor, F. Flores, and G. Niz, Phys. Rev. D 97, 123524 (2018a), eprint arXiv:1803.00014.

- Milgrom [2020] M. Milgrom, MOND from a brane-world picture (2020), eprint arXiv:1804.05840.

- Oort [1932] J. Oort, Bull. Astron. Inst. Neth. 6, 249 (1932).

- Zwicky [1933] F. Zwicky, Helv. Phys. Acta 6, 110 (1933), [Gen. Rel. Grav.41,207(2009)].

- Smith [1936] S. Smith, Astrophys. J. 83, 23 (1936).

- Rubin and Ford [1970] V. C. Rubin and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J. 159, 379 (1970).

- Rubin et al. [1980] V. C. Rubin, N. Thonnard, and W. K. Ford, Jr., Astrophys. J. 238, 471 (1980).

- Milgrom [1983a] M. Milgrom, Astrophys. J. 270, 365 (1983a).

- Milgrom [1983b] M. Milgrom, Astrophys. J. 270, 371 (1983b).

- Milgrom [1983c] M. Milgrom, Astrophys. J. 270, 384 (1983c).

- Bekenstein and Milgrom [1984] J. Bekenstein and M. Milgrom, Astrophys. J. 286, 7 (1984).

- Milgrom [1988] M. Milgrom, Astrophys. J. 333, 689 (1988).

- Kent [1987] S. M. Kent, Astrophys. J. 93, 816 (1987).

- Gerhard and Spergel [1992] O. E. Gerhard and D. N. Spergel, Astrophys. J. 397, 38 (1992).

- Begeman et al. [1991] K. G. Begeman, A. H. Broeils, and R. H. Sanders, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 249, 523 (1991).

- Milgrom [1995] M. Milgrom, Astrophys. J. 455, 439 (1995), eprint astro-ph/9503056.

- Sanders [1996] R. H. Sanders, Astrophys. J. 473, 117 (1996), eprint astro-ph/9606089.

- Sanders [1999] R. H. Sanders, Astrophys. J. Lett. 512, L23 (1999), eprint astro-ph/9807023.

- McGaugh et al. [2000] S. S. McGaugh, J. M. Schombert, G. D. Bothun, and W. J. G. de Blok, Astrophys. J. Lett. 533, L99 (2000), eprint astro-ph/0003001.

- Sanders and McGaugh [2002] R. H. Sanders and S. S. McGaugh, Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 40, 263 (2002), eprint astro-ph/0204521.

- McGaugh [2005] S. S. McGaugh, Astrophys. J. 632, 859 (2005), eprint astro-ph/0506750.

- Famaey and Binney [2005] B. Famaey and J. Binney, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 363, 603 (2005), eprint astro-ph/0506723.

- Bekenstein and Magueijo [2006] J. Bekenstein and J. Magueijo, Phys. Rev. D73, 103513 (2006), eprint astro-ph/0602266.

- Gentile et al. [2007] G. Gentile, B. Famaey, F. Combes, P. Kroupa, H. S. Zhao, and O. Tiret, Astron. Astrophys. 472, L25 (2007), eprint arXiv:0706.1976.

- Magueijo and Mozaffari [2012] J. Magueijo and A. Mozaffari, Phys. Rev. D85, 043527 (2012), eprint arXiv:1107.1075.

- Famaey and McGaugh [2012] B. Famaey and S. McGaugh, Living Rev. Rel. 15, 10 (2012), eprint arXiv:1112.3960.

- Hees et al. [2016] A. Hees, B. Famaey, G. W. Angus, and G. Gentile, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 455, 449 (2016), eprint arXiv:1510.01369.

- Margalit and Shaviv [2016] B. Margalit and N. J. Shaviv, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 456, 1163 (2016), eprint arXiv:1505.04790.

- McGaugh et al. [2016] S. S. McGaugh, F. Lelli, and J. M. Schombert, Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 201101 (2016), eprint arXiv:1609.05917.

- Hodson and Zhao [2017] A. O. Hodson and H. Zhao (2017), eprint arXiv:1703.10219.

- Bílek et al. [2018] M. Bílek, I. Thies, P. Kroupa, and B. Famaey, Astron. Astrophys. 614, A59 (2018), eprint arXiv:1712.04938.

- Sanders [2019] R. H. Sanders, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 485, 513 (2019), eprint arXiv:1811.05260.

- Lelli et al. [2019] F. Lelli, S. S. McGaugh, J. M. Schombert, H. Desmond, and H. Katz, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 484, 3267 (2019), eprint arXiv:1901.05966.

- Petersen and Lelli [2020] J. Petersen and F. Lelli, Astron. Astrophys. 636, A56 (2020), eprint arXiv:2001.03348.

- Blanchet [2007] L. Blanchet, Class. Quant. Grav. 24, 3529 (2007), eprint astro-ph/0605637.

- Blanchet and Le Tiec [2009] L. Blanchet and A. Le Tiec, Phys. Rev. D 80, 023524 (2009), eprint arXiv:0901.3114.

- Berezhiani and Khoury [2016] L. Berezhiani and J. Khoury, Phys. Lett. B753, 639 (2016), eprint arXiv:1506.07877.

- Berezhiani and Khoury [2015] L. Berezhiani and J. Khoury, Phys. Rev. D92, 103510 (2015), eprint arXiv:1507.01019.

- Pardo and Spergel [2020] K. Pardo and D. N. Spergel, Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 211101 (2020), eprint arXiv:2007.00555.

- Bekenstein [1988] J. D. Bekenstein, Phys. Lett. B202, 497 (1988).

- Sanders [1997] R. H. Sanders, Astrophys. J. 480, 492 (1997), eprint astro-ph/9612099.

- Bekenstein [2004] J. D. Bekenstein, Phys. Rev. D70, 083509 (2004), ;71, 069901 (E) (2005).

- Navarro and Van Acoleyen [2006] I. Navarro and K. Van Acoleyen, JCAP 0609, 006 (2006), eprint gr-qc/0512109.

- Zlosnik et al. [2007] T. G. Zlosnik, P. G. Ferreira, and G. D. Starkman, Phys. Rev. D75, 044017 (2007), eprint astro-ph/0607411.

- Sanders [2007] R. H. Sanders, Lect. Notes Phys. 720, 375 (2007), eprint astro-ph/0601431.

- Milgrom [2009a] M. Milgrom, Phys. Rev. D80, 123536 (2009a), eprint arXiv:0912.0790.

- Babichev et al. [2011] E. Babichev, C. Deffayet, and G. Esposito-Farese, Phys. Rev. D84, 061502(R) (2011), eprint arXiv:1106.2538.

- Deffayet et al. [2011] C. Deffayet, G. Esposito-Farese, and R. P. Woodard, Phys. Rev. D84, 124054 (2011), eprint arXiv:1106.4984.

- Woodard [2015] R. P. Woodard, Can. J. Phys. 93, 242 (2015), eprint arXiv:1403.6763.

- Khoury [2015] J. Khoury, Phys. Rev. D91, 024022 (2015), eprint arXiv:1409.0012.

- Blanchet and Heisenberg [2015] L. Blanchet and L. Heisenberg, Phys. Rev. D 91, 103518 (2015), eprint arXiv:1504.00870.

- Hossenfelder [2017] S. Hossenfelder, Phys. Rev. D 95, 124018 (2017), eprint arXiv:1703.01415.

- Burrage et al. [2019] C. Burrage, E. J. Copeland, C. Kading, and P. Millington, Phys. Rev. D 99, 043539 (2019), eprint arXiv:1811.12301.

- Milgrom [2019] M. Milgrom, Phys. Rev. D 100, 084039 (2019), eprint arXiv:1908.01691.

- D’Ambrosio et al. [2020] F. D’Ambrosio, M. Garg, and L. Heisenberg, Phys. Lett. B 811, 135970 (2020), eprint arXiv:2004.00888.

- Skordis et al. [2006] C. Skordis, D. F. Mota, P. G. Ferreira, and C. Boehm, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 011301 (2006), eprint astro-ph/0505519.

- Bourliot et al. [2007] F. Bourliot, P. G. Ferreira, D. F. Mota, and C. Skordis, Phys. Rev. D75, 063508 (2007), eprint astro-ph/0611255.

- Dodelson and Liguori [2006] S. Dodelson and M. Liguori, Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 231301 (2006), eprint astro-ph/0608602.

- Zuntz et al. [2010] J. Zuntz, T. G. Zlosnik, F. Bourliot, P. G. Ferreira, and G. D. Starkman, Phys. Rev. D81, 104015 (2010), eprint arXiv:1002.0849.

- Xu et al. [2015] X.-d. Xu, B. Wang, and P. Zhang, Phys. Rev. D92, 083505 (2015), eprint arXiv:1412.4073.

- Dai and Stojkovic [2017a] D.-C. Dai and D. Stojkovic, Phys. Rev. D 96, 108501 (2017a), eprint arXiv:1706.07854.

- Dai and Stojkovic [2017b] D.-C. Dai and D. Stojkovic, JHEP 11, 007 (2017b), eprint arXiv:1710.00946.

- Zlosnik and Skordis [2017] T. G. Zlosnik and C. Skordis, Phys. Rev. D95, 124023 (2017), eprint arXiv:1702.00683.

- Tan and Woodard [2018] L. Tan and R. P. Woodard, JCAP 1805, 037 (2018), eprint arXiv:1804.01669.

- Sanders [2005] R. Sanders, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 363, 459 (2005), eprint astro-ph/0502222.

- Milgrom [1997] M. Milgrom, Phys. Rev. E56, 1148 (1997), eprint gr-qc/9705003.

- Milgrom [2009b] M. Milgrom, Astrophys. J. 698, 1630 (2009b), eprint arXiv:0810.4065.

- Milgrom [1999] M. Milgrom, Phys. Lett. A 253, 273 (1999), eprint astro-ph/9805346.

- Klinkhamer and Kopp [2011] F. Klinkhamer and M. Kopp, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 26, 2783 (2011), eprint arXiv:1104.2022.

- Verlinde [2017] E. P. Verlinde, SciPost Phys. 2, 016 (2017), eprint arXiv:1611.02269.

- Will [2014] C. M. Will, Living Rev. Rel. 17, 4 (2014), eprint arXiv:1403.7377.

- Will [2018] C. M. Will, Theory and Experiment in Gravitational Physics (Cambridge University Press, 2018), ISBN 9781108679824, 9781107117440.

- Kopp et al. [2018] M. Kopp, C. Skordis, D. B. Thomas, and S. Ilić, Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 221102 (2018), eprint arXiv:1802.09541.

- Ilić et al. [2021] S. Ilić, M. Kopp, C. Skordis, and D. B. Thomas, Phys. Rev. D 104, 043520 (2021).

- Scherrer [2004] R. J. Scherrer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 011301 (2004), eprint astro-ph/0402316.

- Arkani-Hamed et al. [2004] N. Arkani-Hamed, H.-C. Cheng, M. A. Luty, and S. Mukohyama, JHEP 05, 074 (2004), eprint hep-th/0312099.

- Arkani-Hamed et al. [2007] N. Arkani-Hamed, H.-C. Cheng, M. A. Luty, S. Mukohyama, and T. Wiseman, JHEP 01, 036 (2007), eprint hep-ph/0507120.

- Dirac [1962] P. A. M. Dirac, Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A268, 57 (1962).

- Jacobson and Mattingly [2001] T. Jacobson and D. Mattingly, Phys. Rev. D64, 024028 (2001), eprint gr-qc/0007031.

- Abbott et al. [2017] B. Abbott et al. (Virgo, LIGO Scientific), Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 161101 (2017), eprint arXiv:1710.05832.

- Goldstein et al. [2017] A. Goldstein et al., Astrophys. J. 848, L14 (2017), eprint arXiv:1710.05446.

- Savchenko et al. [2017] V. Savchenko et al., Astrophys. J. 848, L15 (2017), eprint arXiv:1710.05449.

- Boran et al. [2018] S. Boran, S. Desai, E. O. Kahya, and R. P. Woodard, Phys. Rev. D97, 041501(R) (2018), eprint arXiv:1710.06168.

- Gong et al. [2018] Y. Gong, S. Hou, D. Liang, and E. Papantonopoulos, Phys. Rev. D97, 084040 (2018), eprint arXiv:1801.03382.

- Hou and Gong [2018] S. Hou and Y. Gong (2018), [Universe4,no.8,84(2018)], eprint arXiv:1806.02564.

- Skordis and Zlosnik [2019] C. Skordis and T. Zlosnik, Phys. Rev. D100, 104013 (2019), eprint arXiv:1905.09465.

- Zlosnik et al. [2006] T. G. Zlosnik, P. G. Ferreira, and G. D. Starkman, Phys. Rev. D74, 044037 (2006), eprint gr-qc/0606039.

- Skordis and Zlosnik [2021a] C. Skordis and T. G. Zlosnik, in preparation (2021a).

- Aghanim et al. [2020] N. Aghanim et al. (Planck), Astron. Astrophys. 641, A6 (2020), [Erratum: Astron.Astrophys. 652, C4 (2021)].

- Kaplinghat et al. [2002] M. Kaplinghat, L. Knox, and C. Skordis, Astrophys. J. 578, 665 (2002), eprint astro-ph/0203413.

- Bellini et al. [2018] E. Bellini et al., Phys. Rev. D 97, 023520 (2018), eprint arXiv:1709.09135.

- Skordis et al. [2021] C. Skordis, S. Ilić, and T. G. Zlosnik, in preparation (2021).

- Reid et al. [2010] B. A. Reid et al., Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 404, 60 (2010), eprint arXiv:0907.1659.

- Skordis and Zlosnik [2021b] C. Skordis and T. Zlosnik (2021b), eprint arXiv:2109.13287.

- Bataki et al. [2021] M. Bataki, C. Skordis, and T. G. Zlosnik, in preparation (2021).

- Gumrukcuoglu et al. [2016] A. E. Gumrukcuoglu, S. Mukohyama, and T. P. Sotiriou, Phys. Rev. D 94, 064001 (2016), eprint arXiv:1606.00618.

- Sanders [2003] R. H. Sanders, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 342, 901 (2003), eprint astro-ph/0212293.

- Pointecouteau and Silk [2005] E. Pointecouteau and J. Silk, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 364, 654 (2005), eprint astro-ph/0505017.

- Ettori et al. [2019] S. Ettori, V. Ghirardini, D. Eckert, E. Pointecouteau, F. Gastaldello, M. Sereno, M. Gaspari, S. Ghizzardi, M. Roncarelli, and M. Rossetti, Astron. Astrophys. 621, A39 (2019), eprint arXiv:1805.00035.

- Tian et al. [2020] Y. Tian, K. Umetsu, C.-M. Ko, M. Donahue, and I.-N. Chiu, Astrophys. J. 896, 70 (2020), eprint arXiv:2001.08340.

- Angus [2008] G. W. Angus, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 387, 1481 (2008), eprint arXiv:0804.3812.

- Serra et al. [2010] A. L. Serra, G. W. Angus, and A. Diaferio, Astron. Astrophys. 524, A16 (2010), eprint arXiv:0907.3691.

- Diez-Tejedor et al. [2018b] A. Diez-Tejedor, A. X. Gonzalez-Morales, and G. Niz, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 477, 1285 (2018b), eprint arXiv:1612.06282.

- Alexander et al. [2017] S. G. Alexander, M. J. Walentosky, J. Messinger, A. Staron, B. Blankartz, and T. Clark, Astrophys. J. 835, 233 (2017).

- Read et al. [2019] J. I. Read, M. G. Walker, and P. Steger, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 484, 1401 (2019), eprint arXiv:1808.06634.

- Banik et al. [2020] I. Banik, I. Thies, G. Candlish, B. Famaey, R. Ibata, and P. Kroupa, Astrophys. J. 905, 135 (2020), eprint arXiv:2011.12293.

- Pittordis and Sutherland [2019] C. Pittordis and W. Sutherland, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 488, 4740 (2019), eprint arXiv:1905.09619.

- Nakashima and Kobayashi [2011] M. Nakashima and T. Kobayashi, Phys. Rev. D 84, 084051 (2011), eprint arXiv:1103.2197.

- Lee et al. [2020] J. G. Lee, E. G. Adelberger, T. S. Cook, S. M. Fleischer, and B. R. Heckel, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 101101 (2020), eprint arXiv:2002.11761.

- Cheng et al. [2006] H.-C. Cheng, M. A. Luty, S. Mukohyama, and J. Thaler, JHEP 05, 076 (2006), eprint hep-th/0603010.

- Kostelecky and Samuel [1989a] V. A. Kostelecky and S. Samuel, Phys. Rev. D 39, 683 (1989a).

- Kostelecky and Samuel [1989b] V. A. Kostelecky and S. Samuel, Phys. Rev. D 40, 1886 (1989b).