Identification of Pre-flare Processes and Their Possible Role in Driving a Large-scale Flux Rope Eruption with Complex M-class Flare in the Active Region NOAA 12371

keywords:

Active Regions, Magnetic Fields; Flares, Dynamics, Pre-Flare Phenomena, Relation to Magnetic Field; Magnetic fields, Models; X-Ray Bursts, Association with Flares1 Introduction

intro Solar flares belong to the most spectacular phenomena occurring in the solar system. During a flare, catastrophic energy release of the order as high as 1027–1032 erg occurs in the solar atmosphere within tens of minutes. The released energy manifests its signatures in the entire electromagnetic spectrum in the form of heat and particle acceleration (see reviews by Fletcher et al., 2011; Benz, 2017). Major flares are often associated with large-scale eruption of plasma from the solar corona known as coronal mass ejection (CME). Earth-directed CMEs are known to cause geomagnetic storms and other hazardous effects at the near-Earth environment. The precise understanding of the magnetic configuration of the flare producing active regions (ARs) during the pre-flare phase and its role in triggering the large-scale eruptions are among the most critical topics studied in the solar physics community (see e.g., Mitra and Joshi, 2019).

The “standard flare model”, also known as CSHKP model (Carmichael, 1964; Sturrock, 1966; Hirayama, 1974; Kopp and Pneuman, 1976), recognizes the presence of magnetic flux rope (MFR) in the AR corona as the prerequisite for the initiation of eruptive flares. An MFR is recognised as sets of magnetic field lines which are twisted around its central axis more than once (Gibson and Fan, 2006). These complex structures are believed to be formed as a result of flux cancellation over the polarity inversion line (PIL) through photospheric shearing and converging motions (van Ballegooijen and Martens, 1989); however, the exact mechanism for flux rope formation is still unclear and debatable. Observationally, MFRs have been identified in the form of different solar features, such as, filaments, prominences, filament channels, hot coronal channels, and coronal sigmoids. Filaments are threadlike structures which are observed as dark long narrow features in the chromospheric images of the Sun (Zirin, 1988; Martin, 1998). When these structures are observed over the limb, they appear brighter than the background sky and are called prominences (Tandberg-Hanssen, 1995; Parenti, 2014). Filament channels are voids without plages or chromospheric fine structures such as spicules or fibrils etc. (Martres and Michard, 1966; Gaizauskas et al., 1997). These are long, narrow, extended structures situated over the PIL where filaments or prominences are formed (Engvold, 1997).

While filaments and filament channels are observed in the absorption lines of choromospheric images, sigmoids and hot channels are observed in the emission line features of the solar corona. Sigmoids are “S” (or inverted “S”) shaped structures that are observed in the soft X-ray (SXR) and the extreme ultra-violet (EUV) images of the Sun (Rust and Kumar, 1996; Manoharan et al., 1996). Hot channels are coherent structures observed in the high temperature pass-band EUV images of the solar corona (Zhang, Cheng, and Ding, 2012; Cheng et al., 2013). These are often found in association with coronal sigmoids (see e.g., Cheng et al., 2014a; Joshi et al., 2017; Mitra et al., 2018). Their frequent co-existence with filaments confirms that filaments and hot channels are different observational manifestations of MFRs lying in the chromospheric and coronal heights, respectively (Cheng et al., 2014b). However, the most important feature of hot channels and coronal sigmoids is their frequent association with CMEs which has been suggested by several case studies and statistical surveys (see e.g., Nindos et al., 2015).

The temporal evolution of a typical eruptive flare can be summarized in three phases: pre-flare/precursor phase, impulsive phase, and gradual phase. While the processes occurring during the impulsive and gradual phases are broadly explained by the CSHKP model (Shibata, 1996), the pre-flare phase is still ill-understood. Pre-flare activities are considered to be important in order to understand the physical conditions that lead to flares and associated eruptions (see e.g., Fárník, Hudson, and Watanabe, 1996; Chifor et al., 2006; Joshi et al., 2011). Although, it is well understood that a significant fraction of all the major flares are associated with pre-flare events, the causal relation between them requires investigation in detail through multi-wavelength case studies. Thanks to the high resolution and high cadence observations of the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA; Lemen et al., 2012) and the Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI; Schou et al., 2012) on board the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO; Pesnell, Thompson, and Chamberlin, 2012), in the recent years, there has been a progress in understanding the short lived pre-flare events and precursor emission.

In this article we present a detailed multi-wavelength analysis of the pre-flare processes associated with a dual-peak M-class flare on 21 June 2015. The reported events occurred in the AR NOAA 12371 which was among the prominent ARs of the solar cycle 24. The M-class flares produced by this AR on 21 and 22 June 2015 have been subjected to a number of studies (see e.g., Manoharan et al., 2016; Cheng and Ding, 2016; Jing et al., 2017; Vemareddy, 2017; Piersanti et al., 2017; Bi et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018; Kuroda et al., 2018; Joshi et al., 2018; Gopalswamy et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019). Our rigorous analysis aims towards providing clear understanding of the pre-flare energy release processes and the role of the pre-flare activity in triggering the flux rope eruption during the complex M-class flare that displayed characteristics of a long duration event (LDE) of energy release. Section \irefdata provides a detailed account of the observational data and analysis techniques used in this article. In Section \irefar, we discuss the evolution of the AR NOAA 12371 in detail. The results obtained on the basis of multi-wavelength analysis and photospheric measurements are discussed in Section \irefobs. Non-linear force free field (NLFFF) extrapolation results and evolution of magnetic free energy in the AR are provided in Section \irefsec_nlfff. We discuss and interpret our results in Section \irefdiscus.

2 Observational Data and Methods

data Solar observation in EUV wavelengths were obtained from the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA; Lemen et al., 2012) on board the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO; Pesnell, Thompson, and Chamberlin, 2012). Among the seven EUV filters of AIA (94 Å, 131 Å, 171 Å, 193 Å, 211 Å, 304 Å, and 335 Å), we have focussed on the 40964096 pixel full-disk solar images in the 94 and 304 Å channels at a spatial resolution of 6 pixel-1 and temporal cadence of 12 s.

For studying the photospheric structures and their evolution, we have used intensity and magnetogram images taken by the Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI; Schou et al., 2012) on board SDO. HMI produces full-disk line of sight (LOS) intensity (continuum) and magnetogram images of 40964096 pixels at a spatial resolution of 5 pixel-1 and 45 s temporal cadence while the vector magnetograms are produced with a temporal cadence of 720 s.

Coronal magnetic field extrapolation has been carried out by employing the optimization based non-linear force free field (NLFFF) extrapolation method developed by Wiegelmann and Inhester (2010); Wiegelmann et al. (2012), using photospheric vector magnetograms from the “hmi.sharp_cea_720s” series of HMI/SDO at a spatial resolution of 0 pixel-1 as boundary conditions. Extrapolations have been done in a Cartesian volume of 474226226 pixels which translates to a physical volume with dimensions 344164164 Mm. Using NLFFF extrapolation results, we calculated the squashing factor (Q) in the extrapolation-volume by employing the code introduced by Liu et al. (2016). For visualizing the extrapolated coronal field lines, we have used Visualization and Analysis Platform for Ocean, Atmosphere, and Solar Researchers (VAPOR; Clyne et al., 2007) software.

X-ray observation during the flare was provided by the Reuven Ramaty High Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI; Lin et al., 2002). RHESSI observed the full Sun with an unprecedented spatial resolution (as fine as ) and energy resolution (1–5 keV) in the energy range 3 keV–17 MeV. For imaging of the X-ray sources using RHESSI observation, we have used the CLEAN algorithm (Hurford et al., 2002) with the natural weighting scheme for front detector segments 2–9 (excluding 7).

3 Magnetic Structure of the Active Region NOAA 12371

ar

3.1 Morphology and Build-up of Magnetic Complexity

morp The AR NOAA 12371 appeared on the eastern limb of the Sun during the last hours of 15 June 2015 as a moderately complex -type sunspot. Flaring activity from the AR was noted to start from 16 June 2015. Interestingly, despite producing numerous B and C class flares alongside few M-class ones, it did not produce any X-class flare. By 18 June 2015, it gradually became a more complex -type sunspot (Figure \irefar_eva) and produced its first M-class flare on the same day. The AR evolved into the most complex -type (Figure \irefar_evb) on the next day, i.e. 19 June 2015. The highest flaring activity from the AR was observed during 20–22 June 2015. In this duration, it produced 3 M-class flares along with many C and B-class flares. The AR started to decay after 22 June 2015. In Table \ireftable1, we summarise various evolutionary aspects of NOAA 12371 during its disk passage during 18–25 June 2015 which are collected from the NOAA Solar Region Summary (SRS) reports111see https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/products/solar-region-summary.. The magnetic configuration of the AR reduced to -type on 25 June 2015 (Figure \irefar_evh) and even further to -type on 29 June 2015 just before it went on to the far side of the Sun from the western limb. During its lifetime on the visible hemisphere of the Sun, it produced a total of 5 M-class flares which are also listed in Table \ireftable1. Notably, the AR produced the largest flare of class M7.9 on 25 June 2015 when it had entered into the declining phase. However, in terms of space weather manifestations, the most interesting eruptive flare from the AR occurred on 21 June 2015. This event followed the characteristics of a long duration flare with peak GOES flux reaching a level of M2.6 and a fast CME222see https://cdaw.gsfc.nasa.gov/CME_list/index.html. with linear speed of 1366 km s-1.

| Sr. | Date | Heliographic | AR | Area (Millionth | GOES flare class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | co-ordinates | configuration | of hemisphere) | (peak time (UT)) | |

| 1 | 2015 June 18 | N12E53 | 520 | M3.0 (17:36) | |

| 2 | 2015 June 19 | N12E39 | 810 | — | |

| 3 | 2015 June 20 | N13E27 | 1020 | M1.0 (06:48) | |

| 4 | 2015 June 21 | N13E14 | 1120 | M2.6 (02:36) | |

| 5 | 2015 June 22 | N13W00 | 1180 | M6.5 (18:23) | |

| 6 | 2015 June 23 | N13W13 | 1070 | — | |

| 7 | 2015 June 24 | N12W28 | 950 | — | |

| 8 | 2015 June 25 | N11W40 | 740 | M7.9 (08:16) |

3.2 Evolution of Photospheric Magnetic Flux

pfmg To have a comprehensive understanding of the photospheric magnetic activities during the prolonged phase of energy build up and subsequent flaring activity on 21 June 2015, we have thoroughly examined large as well as small-scale changes in the LOS magnetograms. During this period, the AR was consisted of two major sunspot groups (Figure \irefar_phota). A comparison of the white light image of the AR with a co-temporal magnetogram (cf. Figures \irefar_phota and b) reveals that almost all of the leading sunspot group of the AR was consisted of negative polarity while the trailing sunspot group was of mixed polarities forming -type configuration. In this manner, the overall photospheric configuration of magnetic polarities of the AR made it a sunspot region.

In Figure \irefhmi_lightcurve, we plot the evolution of the LOS magnetic flux through the whole AR as well as only from the trailing sunspot region from 20 June 2015 12:00 UT to 21 June 2015 05:00 UT. The trailing sunspot group has been shown within the box in Figure \irefhmi_lightcurvea. Notably, the eruptive flare under investigation was triggered from this region. The evolution of the trailing sunspot group of the AR can be inferred by comparing Figures \irefhmi_lightcurveb1 and \irefhmi_lightcurveb2 which present enlarged view of the selected region at two different times. The area marked by dashed circles shows rapidly evolving magnetic elements and moving magnetic features (MMFs) which are discussed in the next subsection. From Figure \irefhmi_lightcurvec, we readily find that both the positive and negative flux from the AR increased during 13:30 UT–23:00 UT on 20 June 2015 and thereafter decreased till the onset of the flare at 01:05 UT on 21 June 2015. Based on the flux variations, we have divided the whole interval in two phases: “phase 1”; when the active region displayed flux enhancement in both the polarities, and “phase 2”; when flux of both polarities decayed. Evolution of magnetic flux in the trailing sunspot group, (i.e. the flaring region) displayed similar variation as the entire AR (Figure \irefhmi_lightcurved). In phase 1, flux of both polarities increased; however, increase of positive flux was more than that of negative flux. Flux of both polarities decayed at similar rate during phase 2. To have an understanding of flaring activity in the AR, we have plotted the variation of GOES SXR flux along with AIA 94 Å light curve from 20 June 2015 12:00 UT to 21 June 2015 05:00 UT in Figure \irefhmi_lightcurvee. We find that, during the selected interval, there was no appreciable enhancement of SXR and EUV fluxes prior to the onset of the M-class flare on 21 June 2015 at 01:05 UT.

3.3 Sunspot Rotation and Moving Magnetic Features

The AR NOAA 12371 underwent significant morphological changes prior to the reported flare which include MMFs, emerging/cancelling flux elements, and sunspot rotation. To highlight these features, we have identified two sub-regions in the AR with most prominent photospheric changes which are marked by the red and blue coloured boxes in Figure \irefar_photb. The leading sunspot group of the AR (inside the red box in Figure \irefar_photb) was associated with a very interesting display of morphological evolution (see the animation associated with Figure \irefar_phot). We note that, the extension of the leading sunspot group along the east-west direction increased from 55′′ at 20 June 2015 12:00 UT to 65′′ prior to the onset of the flare. During the same time, the north-south extension of the leading sunspot group decreased from 40′′ to 35′′ (cf. Figures \irefmag_rota and f). Further, a small circular element of negative polarity (indicated by the blue arrows in Figure \irefmag_rot) exhibited continuous motion along the southern boundary of the leading sunspot group. The diagonal expansion of the region alongside the motions of the small patch suggest “clockwise rotation” of the overall leading sunspot group. We also identify a distinct patch of small magnetic region (indicated by the red arrows in Figure \irefmag_rot) which, after initially exhibiting constant converging motion toward the major sunspot, merged with it during the final hours of 20 June 2015 (Figure \irefmag_rote).

In Figure \irefmag_mov, we show the evolution of the region inside the blue box (Figure \irefar_photb) where we have indicated two particular features by red and green arrows. The red arrows indicate a striking MMF element of negative polarity which also shows significant morphological changes (see animation with Figure \irefar_phot). The green arrows mark persistent cancellation of a positive flux element as the negative MMF moves toward north-west direction.

4 Multi-wavelength Observations of the Eruptive Flare

obs

4.1 Overview of the Event

overview The temporal evolution of the M-class flare on 21 June 2015 is depicted by the flux variation in the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) 1–8 Å and 0.5–4 Å channels which are plotted between 21 June 2015 00:00 UT and 05:00 UT in Figure \ireflightcurvea. The GOES profiles suggest that the eruptive flare evolved in two phases. According to the GOES 1–8 Å time profile, the event started at 01:20 UT while the peaks of the two subsequent episodes of energy release were recorded at 01:42 and 02:36 UT during which the flux rose to the levels of M2.1 and M2.6, respectively. Further, the flare was associated with two brief pre-flare flux enhancements at 01:05 and 01:14 UT (indicated by the dashed and dotted lines, respectively, in Figure \ireflightcurve). Profile of GOES 0.5–4 Å channel clearly shows that, while the flux enhancement during the first pre-flare peak was quite impulsive and short-lived, it was relatively gradual during the second pre-flare peak. Based on the temporal and spatial characteristics (discussed in the next subsection) of the episodic pre-flare enhancements, we refer them as SXR precursors.

In Figure \ireflightcurveb, we display the intensity variation of AIA (E)UV channels on 21 June 2015 from 00:00 UT to 05:00 UT. We note that, none of the AIA intensity profiles exhibited enhancement during the first GOES precursor while a subtle enhancement was observed during the second precursor in the AIA 304 and 171 Å channels (cf. the dashed and dotted lines in Figure \ireflightcurvea and b). Intensity in all the AIA channels, except the 94 Å channel, displayed a sharp peak at 01:36 UT (indicated by the solid line in Figure \ireflightcurveb) while the second peak in these AIA channels was rather gradual. The intensity variation in the AIA 94 Å channel diverged from other AIA channels in the timing and extended duration of the peaks. Interestingly, the AIA 94 Å channel displayed three distinct peaks, first and second ones of which were consistent with the GOES M2.1 and the GOES M2.6 peaks, respectively. The highest of the three AIA 94 Å peaks occurred during the gradual phase of the M-class flare. The flare moved into the gradual phase after 03:00 UT in all the AIA (E)UV and GOES SXR channels.

4.2 Two-phase Flare Emission and Flux Rope Eruption

flare In Figure \ireffl94, we plot a series of AIA 94 Å images displaying the AR NOAA 12371 during different phases of the M-class flare. We readily observe the presence of a prominent hot channel at the core of the AR during the pre-flare phase (indicated by the yellow arrow in Figure \ireffl94b). Comparison of the location of the hot channel with the HMI LOS magnetogram contours in Figure \ireffl94a confirms that the hot channel was lying over the PIL in the trailing sunspot of the AR. After 00:52 UT, we observed a localized yet prominent brightening from a location near to the hot channel (indicated by the red arrow in Figure \ireffl94b). We note that, hard X-ray (HXR) emission of energies up to 25 keV originated from this location of pre-flare EUV brightenings. The examination of series of AIA 94 Å images suggest that the brightness of this localized region initially increased up to 01:05 UT and then decreased till 01:10 UT before increasing again. These pre-flare episodic brightenings observed in AIA 94 Å images are exactly co-temporal with the GOES SXR precursors observed at 01:05 UT and 01:14 UT (cf. Figure \ireflightcurvea). A very interesting phenomena was observed around 01:28 UT in terms of anti-clockwise motion of brightness depicting a narrow semicircular path from the northern end of the region of precursor brightening to the northern leg of the hot channel. This moving flash in indicated by the red arrows in Figures \ireffl94c and d. The flare entered into the impulsive rise phase by 01:20 UT as the hot channel got activated. During this time, we noted HXR emission of energies up to 25 keV predominantly from the northern part of the hot channel. The progression of brightness from the adjacent precursor region to the northern leg of the hot channel was immediately followed by eruption of the hot channel, i.e. the eruption was triggered. In Figure \ireffl94d, we indicate the direction of the hot channel eruption by the blue arrows. The eruption phase was followed by formation of post flare arcade in the trailing sunspot (Figures \ireffl94e and f) which are associated with HXR emission of energies up to 25 keV. A second phase of the eruption was observed between 01:53 UT and 02:05 UT followed by further restructuring of the AR loops at even larger scales, as inferred from the formation of large post flare arcade connecting the trailing sunspot with the leading sunspot. The large post-flare arcade was associated with strong diffused emission till 02:40 UT (Figure \ireffl94g) when the flare reached its second peak. The active region did not show any significant morphological change afterwards till the end of our studied period except the brightness of the large post flare arcade slowly reduced as the flare had moved into the gradual phase (Figures \ireffl94h, i). The above observations led Joshi et al. (2018) to conclude that two distinct phases of magnetic reconnection occurred successively at two separate locations and heights of the AR corona in the wake of single, large hot channel eruption. Based on the temporal and spatial proximity of the two distinct energy release phases along with spectral characteristics of emission, Lee et al. (2018) has termed the two-phases of energy release as the signature of a “composite flare” triggered by the flux rope eruption.

To have a further clarification on the triggering of the hot channel eruption, we selected three slits and computed time-slice diagrams along them (Figure \ireftriggering). These time-slice diagrams can be effectively used to observe the time evolution of plasma eruption and brightness progression along the selected slits (see also the animation associated with Figure \ireftriggering). From Figure \ireftriggeringb, we find that the motion of brightness (apparent signatures of slipping reconnection) from the precursor location started at 01:26 UT. We have highlighted the motion of the brightness in Figure \ireftriggeringb by a dotted curve. The estimated time of the arrival of the brightness at the T2 point is indicated by the dashed vertical line in Figures \ireftriggeringb–c. From Figures \ireftriggeringc and d, it becomes evident that the eruption started immediately after the progression of brightness reached the core of the AR, i.e. the eruption was triggered by the processes linked with the moving brightness.

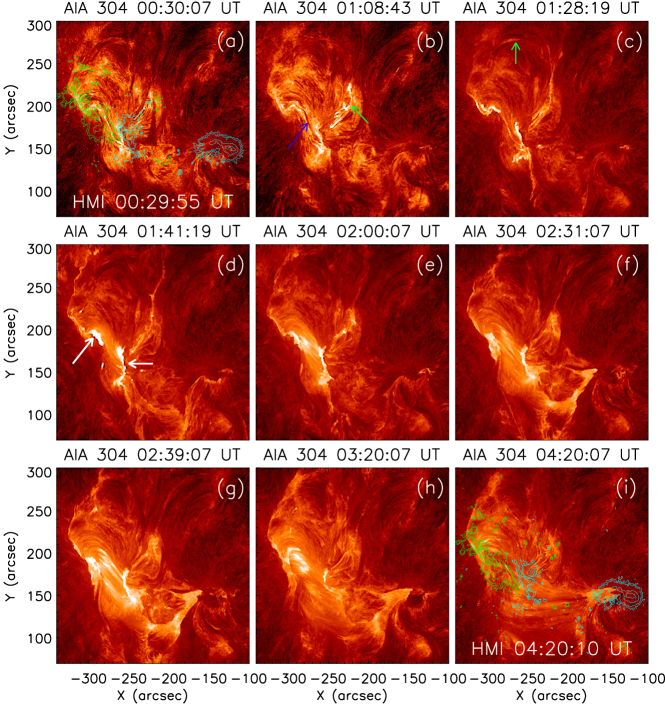

In Figure \ireffl304, we display a series of AIA 304 Å channel showing the evolution of the AR during the M-class flare. A filament (marked by the blue arrow in Figure \ireffl304b) was observed to lie along the PIL in the trailing sunspot region (cf. Figure \ireffl304b with HMI LOS contours in Figure \ireffl304a) which is co-spatial with the location of the hot channel observed in the AIA 94 Å channel images (cf. Figures \ireffl304b and \ireffl94b). The adjacent precursor activity was observed in the AIA 304 Å images also (Figure \ireffl304b and c). During the impulsive phase of the M-class flare, a clear set of flare ribbons formed in the trailing sunspot region (indicated by the arrows in Figure \ireffl304d). As expected from the standard flare scenario, the separation between the two ribbons increased, albeit rather slowly, with time and a dense post flare arcade was eventually formed connecting the two ribbons (Figures \ireffl304d–h).

4.3 Small-scale Pre-eruption Processes

preflare From AIA EUV images (Figures \ireffl94 and \ireffl304) it is clearly understood that the earliest flare brightening occurred at the west of the pre-existing hot channel, (i.e. MFR) which evolved with time but remained within a localized region. As discussed earlier, we identify this brightening as GOES SXR precursor (see Figure \ireflightcurvea). This was followed by the activation and eruption of the hot channel as a sequence of activities. We recall that this region region of precursor brightening was associated with rapidly evolving dispersed magnetic field of positive and negative polarities in which MMFs were observed besides emergence and cancellation of magnetic flux (Figure \irefmag_mov). The precursor activities and its relation to the small-scale magnetic field changes are further analysed in Figure \irefact. In Figure \irefacta, we highlight the region of precursor brightening over the HMI magnetogram by the box and show co-temporal overplots of the AIA 94 Å images with the magnetograms in Figures \irefactb1–b3. We identify several instances of flux emergence and cancellation of both polarities which are indicated by the arrows of different colors and the boxes in Figures \irefactb1–b3. In Figure \irefactc, we show the evolution of LOS magnetic flux from the region shown within the box in Figure \irefacta on 21 June 2015 from 00:00 UT till the onset of the impulsive phase of the flare at 01:20 UT. We find that magnetic flux of both positive and negative polarities exhibited episodic increase and decrease from the region, further implying significant small-scale flux variations. Notably, the overall trend of positive flux in this region displayed a slow decay while the negative flux increased initially up to 00:25 UT and decayed gradually thereafter.

4.4 Morphology and Evolution of Photospheric Longitudinal Current

ph_curr_fe Electric current density on the photosphere, being a direct consequence of flux emergence and decay as well as photospheric motions, is expected to provide important insights toward understanding the onset of flares. The longitudinal component of current density () on the photosphere can be calculated from horizontal components of magnetic field ( and ) using the Ampere’s law (Tan et al., 2006; Kontogiannis et al., 2017):

| (1) |

From current density (), we derive current () by multiplying with the area of one pixel, i.e. 13.141010 m2. In Figure \irefj_var, we plot the temporal evolution of average for the overall active region (Figure \irefj_varb) as well as the location of precursor brightening (Figure \irefj_varc). From the spatial distribution of prior to the hot channel activation (Figure \irefj_vara), we find large concentration of positive and negative currents along the narrow strip delineated by the PIL with the maximum and minimum values of in the active region being 2.091010 A and -2.241010 A, respectively. It is noteworthy that the region displaying precursor brightenings in the corona and underlying MMFs in the photosphere exhibited a complex distribution of . We have indicated this region in the box in Figure \irefj_vara and identify this as the triggering region. We find that in the overall AR, both positive and negative currents experienced a slow variation. Both the positive and negative components of slowly increased during the pre-flare phase of the flare and decreased once the flare onset took place.

In Figure \irefj_img, we show the evolution of the spatial distribution of in the triggering region of the AR (within the box in Figure \irefj_vara). For convenience, we have plotted GOES SXR light curves in Figure \irefj_imga where the timings of the Figures \irefj_imgb–g are indicated by the vertical lines. We find that, in the triggering location, small-scale regions of both positive and negative were mostly distributed randomly. However, an interesting structure of the shape “A” formed by was very clear in the region during the pre-flare phase (outlined by pink-black dashed lines in Figure \irefj_imgb). In the “A” shaped distribution, the left arm was completely made of negative while the right arm was consisted of the positive in the northern part and negative in the southern part. The connecting part of the arms in the “A” was consisted of positive . During the SXR precursor enhancement, in the northern tip of the structure (outlined by the oval shape in Figures \irefj_imgb–g), of opposite polarities became very close to each other (Figures \irefj_imgb and c) which may be ideal for dissipation of current in the form of magnetic reconnection. As Figures \irefj_imgd–g suggest, with the evolution of the flare, strength of at the tip of the “A” significantly decreased and the left arm of the “A” became fragmented (see region inside the box in Figures \irefj_imgb–g). We spotted another interesting feature from Figures \irefj_imgb–g in the form of appearance and decay of a positive current region which we indicate by the black arrows.

5 Non-linear Force Free Field Extrapolation Results

sec_nlfff

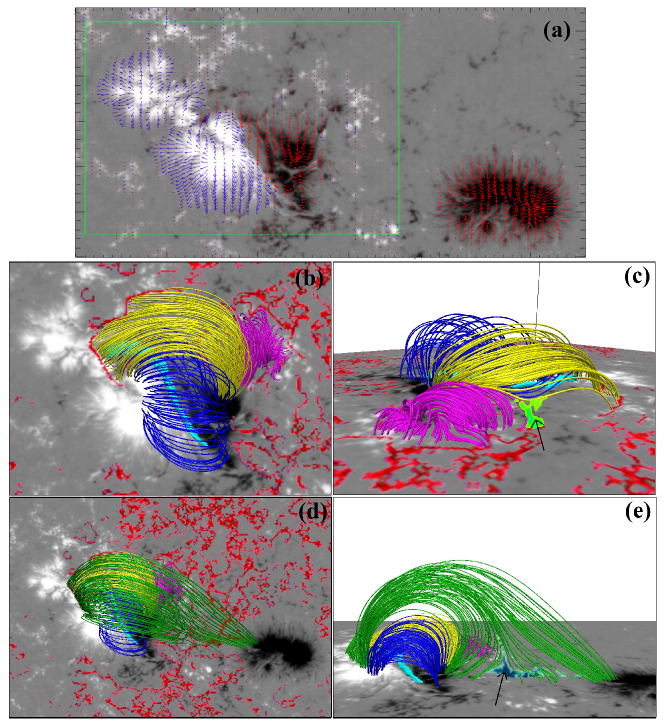

5.1 Modelled Coronal Magnetic Configuration

sec_extrp In order to understand the coronal connectivities between the photospheric magnetic polarities of the AR, we performed a non-linear force free field (NLFFF) extrapolation. For the purpose, we selected an HMI magnetogram at 01:00 UT on 21 June 2015 which represents the photospheric configuration prior to the onset of eruption (Figure \irefnlfffa). In Figures \irefnlfffb and c, we display different sets of NLFFF lines associated with the trailing sunspot group, from top and side views, respectively. The NLFFF extrapolation results readily suggest the presence of an extended flux rope (shown by sky-coloured lines) over the PIL which was enveloped by a set of low coronal closed loops (shown by blue lines) connecting the opposite polarity regions of the trailing sunspot group. Importantly, the modelled flux rope is situated at the same location where the hot coronal channel was identified in the AIA images (cf. Figure \irefnlfffb and \ireffl94a). The coronal configuration associated with the precursor brightening region is displayed by the pink lines in Figure \irefnlfff. Further, we identified a set of closed field lines (shown by the yellow lines) connecting the opposite polarity regions in the trailing sunspot group, a part of which are situated at a very close proximity to the pink lines (see Figure \irefnlfffc). Notably, the anti-clockwise motion of the brightness from the precursor location, clearly revealed by the time-slice diagram shown in Figure \ireftriggeringa, matches reasonably well with the footpoints of the yellow lines. We also note that, a few of the yellow and pink lines displayed a drastic change in the field-line linkage. In literature, such structures are termed as quasi-separatrix layers (QSLs) and are characterised by high squashing factor (Q; see, Priest and Démoulin, 1995). The Q value of this region is found to be higher than 109 (shown by the neon-green coloured patch and the black arrow in Figure \irefnlfffc).

To have a further insight of the anti-clockwise motion of the brightening prior to the eruption of the hot channel, we show the photospheric regions with a Q value greater than 107 by red colour in Figures \irefnlfffb–e. We find that, the footpoints of the yellow lines perfectly match with regions of high Q values (Figure \irefnlfffc) which implies that the anti-clockwise motion of brightness from the precursor location was a slipping reconnection (see e.g., Démoulin et al., 1997; Craig and Effenberger, 2014; Janvier et al., 2016).

In Figures \irefnlfffd and e, we display the coronal connectvities in the whole AR from top and side views, respectively. We note the presence of large coronal loops that connected the positive regions of the trailing sunspot group to the leading negative sunspot group (shown by green lines in Figure \irefnlfffd–e). Also, a part of the green lines originating at the positive polarity region were connected with the adjacent negative polarity region of the same sunspot group. These two sets of green lines constituted a second QSL (log(Q)8) which we have indicated by a black arrow and the blue coloured patch in Figure \irefnlfffd. The observations of spatial progression of brightness within the same region (Figures \ireffl94f–g, \ireffl304f–h and animation associated with Figure \ireflightcurve) are consistent with the scenario of slipping reconnection. Interestingly, the same region of high Q value was associated with a large-scale slipping reconnection event during the M-class flare on 22 June 2015 (Jing et al., 2017) which implies that the large-scale magnetic structure associated with the active region remained preserved on the next day despite the eruption of a halo CME on 21 June 2015.

5.2 Evolution of Magnetic Free Energy

sec_fe The magnetic free energy () associated with an AR is important in order to understand the energy budget of the flares originated from that AR. can be estimated by the formula:

| (2) |

where and are non-potential energy and potential energy, respectively. We have calculated magnetic energy stored in the active region NOAA 12371 by employing the magnetic virial theorem (Klimchuk, Canfield, and Rhoads, 1992). According to this theorem, the magnetic energy stored in a coronal force-free magnetic field is given by the surface integral at the photospheric boundary involving the three vector magnetic field components, i.e.

| (3) |

where , , and are the -, -, and -components of the photospheric magnetic field, respectively. We obtained the 3 components of photospheric magnetic field from the vector magnetograms of the “hmi.sharp_cea_720s” series. The magnetograms were then pre-processed as described in Wiegelmann, Inhester, and Sakurai (2006). We plot the evolution of the free magnetic energy stored in the AR NOAA 12371 normalised by the corresponding potential energy in Figure \irefimfea during the most active phase of AR 12371 (20-22 June, 2015). For reference, we have plotted GOES 1–8 Å SXR flux for the whole duration in Figure \irefimfeb. In this duration, the AR produced 3 M-class flares: class M1.0 on 20 June, class M2.6 on 21 June and class M6.5 on 22 June (see Table \ireftable1). From Figure \irefimfea, we find that prior to the M2.6 and M6.5 class flares, magnetic free energy in the AR 12371 was over 80% of the corresponding potential energy. After both the flares, free energy decreased and reached local minima at 57% and 65% of the corresponding potential energies, respectively. Interestingly, we did not find any significant decrease in magnetic free energy during and after the M-class flare on 20 June, neither free energy increased prior to the flare.

6 Discussion

discus We present a multi-wavelength analysis of the flux rope eruption on 21 June 2015 from the active region NOAA 12371 with a particular emphasis on its triggering mechanism. The automated catalogue of GOES flares333see https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/products/solar-and-geophysical-activity-summary. has enrolled two flares on 21 June 2015. However, from the evolution of the active region from the hot channel to the formation of large post-flare arcade during the two GOES peaks, we can convincingly call the GOES flaring events as flux rope eruption, i.e. a dual-peaked long duration event.

The temporal evolution of the GOES SXR flux suggests that the flare was associated with two-stage precursor emission. Comparison of GOES SXR fluxes with AIA observations confirms that both the episodes of the subtle flux enhancements prior to the flare were caused by localised brightenings in a nearby region situated to the west of the hot channel (Figures \ireffl94, \ireffl304, and \irefact). These localised brightenings indicate energy release at small-scale within the same active region that can provide potential trigger for eruption by destabilizing a stable MFR (Fárník, Hudson, and Watanabe, 1996; Fárník and Savy, 1998; Warren and Warshall, 2001; Fárník et al., 2003; Sterling and Moore, 2005; Fárník et al., 2003; Chifor et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Joshi et al., 2011, 2016, 2017; Woods et al., 2017; Dhara et al., 2017; Woods et al., 2018; Hernandez-Perez et al., 2019; Mitra and Joshi, 2019). Based on the location of small-scale energy release compared to main flaring event, pre-flare events can be categorized in three classes: co-spatial, adjacent/overlapping, and distant (Fárník, Hudson, and Watanabe, 1996; Fárník and Savy, 1998); the present case being an example of adjacent pre-flare activity. Further, the temporal and spatial evolution of the event suggests that pre-flare emission essentially acted as the precursor to the main eruption.

An important aspect of this study is to investigate the origin of the pre-flare activities and their spatial relation with the eruption of the MFR. NLFFF extrapolation results (Figure \irefnlfff) suggests that the triggering region, (i.e. the region of precursor activity) was associated with coronal magnetic loops with high shear (pink lines in Figure \irefnlfff). Zhang (1995) demonstrated that sheared magnetic field leads to the formation of electric current on the photosphere which can be accompanied by flares. Tan et al. (2006) investigated evolution of photospheric current during two flares of classes M1.0 and M8.7 occurring from two different ARs. Although, both the ARs were subjected to rapid flux emergence, the two flares differed significantly in the evolution of photospheric longitudinal current. Their analysis revealed that for the M1.0 flare, the longitudinal electric current density dropped rapidly; while it increased for the case of the M8.7 flare. They concluded rapid emergence of current carrying flux to be responsible for the increasing longitudinal current during the M8.7 flare while their explanation for the decrease of electric current for the M1.0 flare the was dissipation of magnetic free energy in the solar atmosphere. Our analysis suggests that in the triggering location, a few localized regions with high values of vertical component of photospheric electric current with opposite polarities were situated very close to each other (Figure \irefj_img). During the GOES pre-flare peaks, one particular set of regions with opposite polarity longitudinal current became adjacent to each other (within the oval in Figures \irefj_imgb, c) suggesting that the initial reconnection most likely occurred from this location. Once the reconnection began, it induced further reconnection events in the nearby stressed magnetic field lines of the region resulting in the enhancement of plasma temperature. These reconnection events most likely induced a slipping reconnection in the yellow field lines (Figure \irefnlfff) carrying energy from the precursor location to the northern leg of the hot channel leading to its destabilisation. The entire mechanism suggested here is analogous to the domino effect that involve a sequence of destabilising processes that eventually cause a large-scale eruption (Zuccarello, F. et al., 2009).

The AR experienced significant flux emergence for 10 hrs and cancellation thereafter for 2 hrs prior to the onset of the flare (Figures \irefhmi_lightcurvec and d). However, GOES SXR and AIA EUV light curves suggests absence of flaring activity in the AR during this prolonged period (cf. Figures \irefhmi_lightcurvec, d and e) which signifies continuous storage of magnetic energy into the flaring environment without significant dissipation by reconnection events. Therefore, the emergence of magnetic flux in the trailing sunspot region and the subsequent phase of its decay prior to the onset of the flare possibly resulted in the build up of the MFR along the PIL. This is supportive of the flux cancellation model proposed by van Ballegooijen and Martens (1989) which states that flux cancellation at the PIL of a sheared magnetic arcade leads to the formation of MFRs. The build up of the MFR over the PIL in the trailing sunspot group of AR 12371 prior to the M-class flare on 21 June 2015 was observationally inferred by continuous brightening up of the hot channel as observed in AIA 94 Å channel images (Figure \ireffl94a–c). Our analysis suggests that the hot channel continued to acquire the magnetic field and stress in response to the flux cancellation for an elongated period of time during the pre-flare phase. As a result, the MFR had already reached to a meta-stable state prior to the onset of the flare which allowed immediate eruption of it once triggered by the slipping reconnection. This type triggering can be explained by the “tether-weakening” model proposed by Moore and Roumeliotis (1992). According to this model, a meta-stable flux rope can be triggered by activities occurring adjacent to it, i.e. off the main PIL (see e.g., Sterling, Harra, and Moore, 2007; Yang and Chen, 2019).

It is very interesting to note that, the flare originated from the same AR on the next day, (i.e. 22 June 2015) proceeded with the formation and eruption of a hot channel from the trailing sunspot group (see Cheng and Ding, 2016; Wang et al., 2017; Awasthi et al., 2018), similar to the AIA observations of the M-class flare on 21 June, being investigated here. Also, in both the cases, the flux rope eruptions resulted into halo CMEs. However, the underlying flux rope structure of the hot channel bore differences between the events of 21 June and 22 June. By employing NLFFF extrapolation technique, Awasthi et al. (2018) observed multiple braided flux ropes with different degrees of coherency over the PIL during the pre-flare phase, which were separated in height. They also found evidence of small-scale reconnection events among the different flux rope branches which resulted into further braiding among the flux rope threads. While Awasthi et al. (2018) found the internal structure of the MFR on 22 June 2015 to be complex braided magnetic field, our result suggests coherent twisted field as the structure of the MFR. Further, there seems to have differences in the time-sequence and activities associated with the early stages of the MFR activation. Using high resolution observations of the precursor phase of the M6.5 flare on 22 June 2015 from the 1.6-m New Solar Telescope, Wang et al. (2017) found two episodes of small-scale precursor brightening at the magnetic channel prior to the large-scale eruption of the MFR. Based on these observations, they concluded that low-atmospheric small-scale energy release events possibly triggered the eruption which supports the model proposed by Kusano et al. (2012).

During the build up of the flux rope in the trailing sunspot prior to the M-class flare on 21 June, magnetic free energy stored in the AR increased significantly for a period of 5 hours which drastically reduced during the flare (Figure \irefimfe). The M-class flare occurring on the next day from the same AR was subjected to similar type of magnetic energy evolution. These results clearly refer to a direct correlation between accumulation of free energy in the AR and build up of MFR with excess free energy in the form of their twisted (or, braided) magnetic structures.

In summary, the AR NOAA 12371 went through an elaborate phase of flux enhancement followed by a duration of significant flux cancellation which led to build up of an MFR along the PIL in the trailing sunspot group. The AR was associated with highly dynamical features including photospheric motions (i.e. MMFs) and rotation which led to formation of localized regions of high photospheric current densities. Two well identified precursor events preceded the flux rope activation. The precursor region, spatially separated from the location of the MFR, exhibited strong photospheric longitudinal currents of opposite polarities in very close proximity and was connected directly to the MFR through magnetic loops. More importantly, we found evidence for slipping reconnection from the precursor region to the flux rope activation site which eventually destabilised the quasi-evolving MFR, resulting a halo CME and M-class flaring activities. Our study especially addresses the build-up phase of the MFR and the role of precursor activities toward driving the eruption. In future, we aim to study the slipping reconnection in the context of physical processes during the pre-flare and early flare evolution.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the SDO and RHESSI teams for their open data policy. SDO is NASA’s mission under the Living With a Star (LWS) program. RHESSI was the sixth mission in the SMall EXplorer (SMEX) program of NASA. The authors are also thankful to Dr. Thomas Wiegelmann for providing the NLFFF code. AP acknowledges partial support of NASA grant 80NSSC17K0016 and NSF award AGS-1650854. We also acknowledge the constructive

comments and useful suggestions of the anonymous referee, which improved the presentation and scientific content of the article.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Awasthi et al. (2018) Awasthi, A.K., Liu, R., Wang, H., Wang, Y., Shen, C.: 2018, Pre-eruptive magnetic reconnection within a multi-flux-rope system in the solar corona. ApJ 857(2), 124. DOI. ADS.

- Benz (2017) Benz, A.O.: 2017, Flare observations. Living Reviews in Solar Physics 14, 2. DOI. ADS.

- Bi et al. (2017) Bi, Y., Yang, J., Jiang, Y., Hong, J., Xu, Z., Qu, Z., Ji, K.: 2017, The photospheric vortex flows during a solar flare. ApJ 849(2), L35. DOI. ADS.

- Carmichael (1964) Carmichael, H.: 1964, A process for flares. NASA Special Publication 50, 451. ADS.

- Cheng and Ding (2016) Cheng, X., Ding, M.D.: 2016, Spectroscopic diagnostics of solar magnetic flux ropes using Iron forbidden line. ApJ 823(1), L4. DOI. ADS.

- Cheng et al. (2013) Cheng, X., Zhang, J., Ding, M.D., Liu, Y., Poomvises, W.: 2013, The driver of coronal mass ejections in the low corona: A flux rope. ApJ 763, 43. DOI. ADS.

- Cheng et al. (2014a) Cheng, X., Ding, M.D., Zhang, J., Sun, X.D., Guo, Y., Wang, Y.M., Kliem, B., Deng, Y.Y.: 2014a, Formation of a double-decker magnetic flux rope in the sigmoidal solar active region 11520. ApJ 789(2), 93. DOI. ADS.

- Cheng et al. (2014b) Cheng, X., Ding, M.D., Zhang, J., Srivastava, A.K., Guo, Y., Chen, P.F., Sun, J.Q.: 2014b, On the relationship between a hot-channel-like solar magnetic flux rope and its embedded prominence. ApJ 789, L35. DOI. ADS.

- Chifor et al. (2006) Chifor, C., Mason, H.E., Tripathi, D., Isobe, H., Asai, A.: 2006, The early phases of a solar prominence eruption and associated flare: a multi-wavelength analysis. A&A 458, 965. DOI. ADS.

- Chifor et al. (2007) Chifor, C., Tripathi, D., Mason, H.E., Dennis, B.R.: 2007, X-ray precursors to flares and filament eruptions. A&A 472, 967. DOI. ADS.

- Clyne et al. (2007) Clyne, J., Mininni, P., Norton, A., Rast, M.: 2007, Interactive desktop analysis of high resolution simulations: application to turbulent plume dynamics and current sheet formation. New Journal of Physics 9(8), 301. http://stacks.iop.org/1367-2630/9/i=8/a=301.

- Craig and Effenberger (2014) Craig, I.J.D., Effenberger, F.: 2014, Current singularities at quasi-separatrix layers and three-dimensional magnetic nulls. ApJ 795(2), 129. DOI. ADS.

- Démoulin et al. (1997) Démoulin, P., Bagala, L.G., Mandrini, C.H., Henoux, J.C., Rovira, M.G.: 1997, Quasi-separatrix layers in solar flares. II. Observed magnetic configurations. A&A 325, 305. ADS.

- Dhara et al. (2017) Dhara, S.K., Belur, R., Kumar, P., Banyal, R.K., Mathew, S.K., Joshi, B.: 2017, Trigger of successive filament eruptions observed by sdo and stereo. Sol. Phys. 292(10), 145. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-017-1158-4.

- Engvold (1997) Engvold, O.: 1997, In: Mouradian, Z., Stavinschi, M. (eds.) Filament Channels in the Corona, Springer, Dordrecht, 125. ISBN 978-94-011-5492-5. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-5492-5˙22.

- Fárník and Savy (1998) Fárník, F., Savy, S.K.: 1998, Soft X-ray pre-flare emission studied in Yohkoh-SXT images. Sol. Phys. 183, 339. DOI. ADS.

- Fárník, Hudson, and Watanabe (1996) Fárník, F., Hudson, H., Watanabe, T.: 1996, Spatial relations between preflares and flares. Sol. Phys. 165, 169. DOI. ADS.

- Fárník et al. (2003) Fárník, F., Hudson, H.S., Karlický, M., Kosugi, T.: 2003, X-ray and radio observations of the activation stages of an X-class solar flare. A&A 399, 1159. DOI. ADS.

- Fletcher et al. (2011) Fletcher, L., Dennis, B.R., Hudson, H.S., Krucker, S., Phillips, K., Veronig, A., Battaglia, M., Bone, L., Caspi, A., Chen, Q., Gallagher, P., Grigis, P.T., Ji, H., Liu, W., Milligan, R.O., Temmer, M.: 2011, An observational overview of solar flares. Space Sci. Rev. 159, 19. DOI. ADS.

- Gaizauskas et al. (1997) Gaizauskas, V., Zirker, J.B., Sweetland, C., Kovacs, A.: 1997, Formation of a solar filament channel. ApJ 479(1), 448. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1086%2F512788.

- Gibson and Fan (2006) Gibson, S.E., Fan, Y.: 2006, Coronal prominence structure and dynamics: A magnetic flux rope interpretation. Journal of Geophysical Research (Space Physics) 111, A12103. DOI. ADS.

- Gopalswamy et al. (2018) Gopalswamy, N., Mäkelä, P., Akiyama, S., Yashiro, S., Xie, H., Thakur, N.: 2018, Sun-to-earth propagation of the 2015 June 21 coronal mass ejection revealed by optical, EUV, and radio observations. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 179, 225. DOI. ADS.

- Hernandez-Perez et al. (2019) Hernandez-Perez, A., Su, Y., Veronig, A.M., Thalmann, J., Gömöry, P., Joshi, B.: 2019, Pre-eruption processes: heating, particle acceleration, and the formation of a hot channel before the 2012 October 20 M9.0 limb flare. ApJ 874, 122. DOI. ADS.

- Hirayama (1974) Hirayama, T.: 1974, Theoretical model of flares and prominences. Sol. Phys. 34(2), 323. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00153671.

- Hurford et al. (2002) Hurford, G.J., Schmahl, E.J., Schwartz, R.A., Conway, A.J., Aschwanden, M.J., Csillaghy, A., Dennis, B.R., Johns-Krull, C., Krucker, S., Lin, R.P., McTiernan, J., Metcalf, T.R., Sato, J., Smith, D.M.: 2002, The RHESSI imaging concept. Sol. Phys. 210(1), 61. DOI. ADS.

- Janvier et al. (2016) Janvier, M., Savcheva, A., Pariat, E., Tassev, S., Millholland, S., Bommier, V., McCauley, P., McKillop, S., Dougan, F.: 2016, Evolution of flare ribbons, electric currents, and quasi-separatrix layers during an X-class flare. A&A 591, A141. DOI. ADS.

- Jing et al. (2017) Jing, J., Liu, R., Cheung, M.C.M., Lee, J., Xu, Y., Liu, C., Zhu, C., Wang, H.: 2017, Witnessing a large-scale slipping magnetic reconnection along a dimming channel during a solar flare. ApJ 842(2), L18. DOI. ADS.

- Joshi et al. (2011) Joshi, B., Veronig, A.M., Lee, J., Bong, S.-C., Tiwari, S.K., Cho, K.-S.: 2011, Pre-flare activity and magnetic reconnection during the evolutionary stages of energy release in a solar eruptive flare. ApJ 743, 195. DOI. ADS.

- Joshi et al. (2016) Joshi, B., Kushwaha, U., Veronig, A.M., Cho, K.-S.: 2016, Pre-flare coronal jet and evolutionary phases of a solar eruptive prominence associated with the M1.8 flare: SDO and RHESSI observations. ApJ 832, 130. DOI. ADS.

- Joshi et al. (2017) Joshi, B., Kushwaha, U., Veronig, A.M., Dhara, S.K., Shanmugaraju, A., Moon, Y.-J.: 2017, Formation and eruption of a flux rope from the sigmoid active region NOAA 11719 and associated M6.5 flare: a multi-wavelength study. ApJ 834, 42. DOI. ADS.

- Joshi et al. (2018) Joshi, B., Ibrahim, M.S., Shanmugaraju, A., Chakrabarty, D.: 2018, A major geoeffective CME from NOAA 12371: initiation, CME-CME interactions, and interplanetary consequences. Sol. Phys. 293, 107. DOI. ADS.

- Kim et al. (2008) Kim, S., Moon, Y.-J., Kim, Y.-H., Park, Y.-D., Kim, K.-S., Choe, G.S., Kim, K.-H.: 2008, Preflare eruption triggered by a tether-cutting process. ApJ 683(1), 510. DOI. ADS.

- Klimchuk, Canfield, and Rhoads (1992) Klimchuk, J.A., Canfield, R.C., Rhoads, J.E.: 1992, The practical application of the magnetic virial theorem. ApJ 385, 327. DOI. ADS.

- Kontogiannis et al. (2017) Kontogiannis, I., Georgoulis, M.K., Park, S.-H., Guerra, J.A.: 2017, Non-neutralized electric currents in solar active regions and flare productivity. Sol. Phys. 292(11), 159. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-017-1185-1.

- Kopp and Pneuman (1976) Kopp, R.A., Pneuman, G.W.: 1976, Magnetic reconnection in the corona and the loop prominence phenomenon. Sol. Phys. 50, 85. DOI. ADS.

- Kuroda et al. (2018) Kuroda, N., Gary, D.E., Wang, H., Fleishman, G.D., Nita, G.M., Jing, J.: 2018, Three-dimensional forward-fit modeling of the hard X-ray and microwave emissions of the 2015 June 22 M6.5 flare. ApJ 852(1), 32. DOI. ADS.

- Kusano et al. (2012) Kusano, K., Bamba, Y., Yamamoto, T.T., Iida, Y., Toriumi, S., Asai, A.: 2012, Magnetic field structures triggering solar flares and coronal mass ejections. ApJ 760(1), 31. DOI. ADS.

- Lee et al. (2017) Lee, J., White, S.M., Jing, J., Liu, C., Masuda, S., Chae, J.: 2017, Thermal and nonthermal emissions of a composite flare derived from NoRH and SDO observations. ApJ 850(2), 124. DOI. ADS.

- Lee et al. (2018) Lee, J., White, S.M., Liu, C., Kliem, B., Masuda, S.: 2018, Magnetic structure of a composite solar microwave burst. ApJ 856(1), 70. DOI. ADS.

- Lemen et al. (2012) Lemen, J.R., Title, A.M., Akin, D.J., Boerner, P.F., Chou, C., Drake, J.F., Duncan, D.W., Edwards, C.G., Friedlaender, F.M., Heyman, G.F., Hurlburt, N.E., Katz, N.L., Kushner, G.D., Levay, M., Lindgren, R.W., Mathur, D.P., McFeaters, E.L., Mitchell, S., Rehse, R.A., Schrijver, C.J., Springer, L.A., Stern, R.A., Tarbell, T.D., Wuelser, J.-P., Wolfson, C.J., Yanari, C., Bookbinder, J.A., Cheimets, P.N., Caldwell, D., Deluca, E.E., Gates, R., Golub, L., Park, S., Podgorski, W.A., Bush, R.I., Scherrer, P.H., Gummin, M.A., Smith, P., Auker, G., Jerram, P., Pool, P., Soufli, R., Windt, D.L., Beardsley, S., Clapp, M., Lang, J., Waltham, N.: 2012, The Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) on the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). Sol. Phys. 275, 17. DOI. ADS.

- Lin et al. (2002) Lin, R.P., Dennis, B.R., Hurford, G.J., Smith, D.M., Zehnder, A., Harvey, P.R., Curtis, D.W., Pankow, D., Turin, P., Bester, M., Csillaghy, A., Lewis, M., Madden, N., van Beek, H.F., Appleby, M., Raudorf, T., McTiernan, J., Ramaty, R., Schmahl, E., Schwartz, R., Krucker, S., Abiad, R., Quinn, T., Berg, P., Hashii, M., Sterling, R., Jackson, R., Pratt, R., Campbell, R.D., Malone, D., Landis, D., Barrington-Leigh, C.P., Slassi-Sennou, S., Cork, C., Clark, D., Amato, D., Orwig, L., Boyle, R., Banks, I.S., Shirey, K., Tolbert, A.K., Zarro, D., Snow, F., Thomsen, K., Henneck, R., McHedlishvili, A., Ming, P., Fivian, M., Jordan, J., Wanner, R., Crubb, J., Preble, J., Matranga, M., Benz, A., Hudson, H., Canfield, R.C., Holman, G.D., Crannell, C., Kosugi, T., Emslie, A.G., Vilmer, N., Brown, J.C., Johns-Krull, C., Aschwanden, M., Metcalf, T., Conway, A.: 2002, The Reuven Ramaty High-Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI). Sol. Phys. 210, 3. DOI. ADS.

- Liu et al. (2016) Liu, R., Kliem, B., Titov, V.S., Chen, J., Wang, Y., Wang, H., Liu, C., Xu, Y., Wiegelmann, T.: 2016, Structure, stability, and evolution of magnetic flux ropes from the perspective of magnetic twist. ApJ 818(2), 148. DOI. ADS.

- Liu et al. (2019) Liu, R., Wang, Y., Lee, J., Shen, C.: 2019, Impacts of EUV wavefronts on coronal structures in homologous coronal mass ejections. ApJ 870(1), 15. DOI. ADS.

- Liu et al. (2009) Liu, W., Wang, T.-J., Dennis, B.R., Holman, G.D.: 2009, Episoidic x-ray emmision accompanying the activation of an eruptive prominence: evidence of episoidic magnetic reconnection. ApJ 698(1), 632. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1088%2F0004-637x%2F698%2F1%2F632.

- Manoharan et al. (1996) Manoharan, P.K., van Driel-Gesztelyi, L., Pick, M., Démoulin, P.: 1996, Evidence for large-scale solar magnetic reconnection from radio and X-ray measurements. ApJ 468, L73. DOI. ADS.

- Manoharan et al. (2016) Manoharan, P.K., Maia, D., Johri, A., Induja, M.S.: 2016, Interplanetary consequences of coronal mass ejection events occurred during 18-25 June 2015. In: Dorotovic, I., Fischer, C.E., Temmer, M. (eds.) Coimbra Solar Physics Meeting: Ground-based Solar Observations in the Space Instrumentation Era, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series 504, 59. ADS.

- Martin (1998) Martin, S.F.: 1998, Conditions for the formation and maintenance of filaments (Invited Review). Sol. Phys. 182(1), 107. DOI. ADS.

- Martres and Michard (1966) Martres, M., Michard, R.: 1966, Soru-iscovici. Ann. Astrophys 29, 249.

- Mitra and Joshi (2019) Mitra, P.K., Joshi, B.: 2019, Preflare processes, flux rope activation, large-scale eruption, and associated X-class flare from the active region NOAA 11875. ApJ 884(1), 46. DOI. ADS.

- Mitra et al. (2018) Mitra, P.K., Joshi, B., Prasad, A., Veronig, A.M., Bhattacharyya, R.: 2018, Successive flux rope eruptions from -sunspots region of noaa 12673 and associated x-class eruptive flares on 2017 september 6. ApJ 869(1), 69.

- Moore and Roumeliotis (1992) Moore, R.L., Roumeliotis, G.: 1992, Triggering of eruptive flares - destabilization of the preflare magnetic field configuration. In: Svestka, Z., Jackson, B.V., Machado, M.E. (eds.) IAU Colloq. 133: Eruptive Solar Flares, Lecture Notes in Physics, Berlin Springer Verlag 399, 69. DOI. ADS.

- Nindos et al. (2015) Nindos, A., Patsourakos, S., Vourlidas, A., Tagikas, C.: 2015, How common are hot magnetic flux ropes in the low solar corona? a statistical study of euv observations. ApJ 808(2), 117. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1088%2F0004-637x%2F808%2F2%2F117.

- Parenti (2014) Parenti, S.: 2014, Solar prominences: observations. Living Reviews in Solar Physics 11(1), 1. DOI. https://doi.org/10.12942/lrsp-2014-1.

- Pesnell, Thompson, and Chamberlin (2012) Pesnell, W.D., Thompson, B.J., Chamberlin, P.C.: 2012, The Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). Sol. Phys. 275(1), 3. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-011-9841-3.

- Piersanti et al. (2017) Piersanti, M., Alberti, T., Bemporad, A., Berrilli, F., Bruno, R., Capparelli, V., Carbone, V., Cesaroni, C., Consolini, G., Cristaldi, A., Del Corpo, A., Del Moro, D., Di Matteo, S., Ermolli, I., Fineschi, S., Giannattasio, F., Giorgi, F., Giovannelli, L., Guglielmino, S.L., Laurenza, M., Lepreti, F., Marcucci, M.F., Martucci, M., Mergè, M., Pezzopane, M., Pietropaolo, E., Romano, P., Sparvoli, R., Spogli, L., Stangalini, M., Vecchio, A., Vellante, M., Villante, U., Zuccarello, F., Heilig, B., Reda, J., Lichtenberger, J.: 2017, Comprehensive analysis of the geoeffective solar event of 21 June 2015: effects on the magnetosphere, plasmasphere, and ionosphere systems. Sol. Phys. 292(11), 169. DOI. ADS.

- Priest and Démoulin (1995) Priest, E.R., Démoulin, P.: 1995, Three-dimensional magnetic reconnection without null points: 1. basic theory of magnetic flipping. Journal of Geophysical Research (Space Physics) 100(A12), 23443. DOI. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/95JA02740.

- Rust and Kumar (1996) Rust, D.M., Kumar, A.: 1996, Evidence for helically kinked magnetic flux ropes in solar eruptions. ApJ 464, L199. DOI. ADS.

- Schou et al. (2012) Schou, J., Scherrer, P.H., Bush, R.I., Wachter, R., Couvidat, S., Rabello-Soares, M.C., Bogart, R.S., Hoeksema, J.T., Liu, Y., Duvall, T.L., Akin, D.J., Allard, B.A., Miles, J.W., Rairden, R., Shine, R.A., Tarbell, T.D., Title, A.M., Wolfson, C.J., Elmore, D.F., Norton, A.A., Tomczyk, S.: 2012, Design and ground calibration of the Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI) instrument on the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). Sol. Phys. 275, 229. DOI. ADS.

- Shibata (1996) Shibata, K.: 1996, New observational facts about solar flares from YOHKOH studies - evidence of magnetic reconnection and a unified model of flares. Advances in Space Research 17(4-5), 9. DOI. ADS.

- Sterling and Moore (2005) Sterling, A.C., Moore, R.L.: 2005, Slow-rise and fast-rise phases of an erupting solar filament, and flare emission onset. ApJ 630(2), 1148. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1086%2F432044.

- Sterling, Harra, and Moore (2007) Sterling, A.C., Harra, L.K., Moore, R.L.: 2007, New evidence for the role of emerging flux in a solar filament’s slow rise preceding its CME-producing fast eruption. ApJ 669(2), 1359. DOI. ADS.

- Sturrock (1966) Sturrock, P.A.: 1966, Model of the high-energy phase of solar flares. Nature 211, 695. DOI. ADS.

- Tan et al. (2006) Tan, B., Ji, H., Huang, G., Zhou, T., Song, Q., Huang, Y.: 2006, Evolution of electric currents associated with two m-class flares. Sol. Phys. 239(1), 137. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-006-0120-7.

- Tandberg-Hanssen (1995) Tandberg-Hanssen, E.: 1995, Physical Parameters of the Prominence Plasma, Springer, Dordrecht, 81. ISBN 978-94-017-3396-0. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-3396-0˙3.

- van Ballegooijen and Martens (1989) van Ballegooijen, A.A., Martens, P.C.H.: 1989, Formation and eruption of solar prominences. ApJ 343, 971. DOI. ADS.

- Vemareddy (2017) Vemareddy, P.: 2017, Successive homologous coronal mass ejections driven by shearing and converging motions in solar active region NOAA 12371. ApJ 845(1), 59. DOI. ADS.

- Wang et al. (2017) Wang, H., Liu, C., Ahn, K., Xu, Y., Jing, J., Deng, N., Huang, N., Liu, R., Kusano, K., Fleishman, G.D., Gary, D.E., Cao, W.: 2017, High-resolution observations of flare precursors in the low solar atmosphere. Nature Astronomy 1, 0085. DOI. ADS.

- Wang et al. (2018) Wang, J., Liu, C., Deng, N., Wang, H.: 2018, Evolution of photospheric flow and magnetic fields associated with the 2015 June 22 M6.5 flare. ApJ 853(2), 143. DOI. ADS.

- Warren and Warshall (2001) Warren, H.P., Warshall, A.D.: 2001, Ultraviolet flare ribbon brightenings and the onset of hard x-ray emission. ApJ 560(1), L87. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1086%2F324060.

- Wiegelmann and Inhester (2010) Wiegelmann, T., Inhester, B.: 2010, How to deal with measurement errors and lacking data in nonlinear force-free coronal magnetic field modelling? A&A 516, A107. DOI. ADS.

- Wiegelmann, Inhester, and Sakurai (2006) Wiegelmann, T., Inhester, B., Sakurai, T.: 2006, Preprocessing of vector magnetograph data for a nonlinear force-free magnetic field reconstruction. Sol. Phys. 233(2), 215. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11207-006-2092-z.

- Wiegelmann et al. (2012) Wiegelmann, T., Thalmann, J.K., Inhester, B., Tadesse, T., Sun, X., Hoeksema, J.T.: 2012, How should one optimize nonlinear force-free coronal magnetic field extrapolations from SDO/HMI vector magnetograms? Sol. Phys. 281, 37. DOI. ADS.

- Woods et al. (2017) Woods, M.M., Harra, L.K., Matthews, S.A., Mackay, D.H., Dacie, S., Long, D.M.: 2017, Observations and modelling of the pre-flare period of the 29 March 2014 X1 flare. Sol. Phys. 292(2), 38. DOI. ADS.

- Woods et al. (2018) Woods, M.M., Inoue, S., Harra, L.K., Matthews, S.A., Kusano, K., Kalmoni, N.M.E.: 2018, The triggering of the 2014 March 29 filament eruption. ApJ 860(2), 163. DOI. ADS.

- Yang and Chen (2019) Yang, B., Chen, H.: 2019, Filament eruption and its reformation caused by emerging magnetic flux. ApJ 874(1), 96. DOI. ADS.

- Zhang (1995) Zhang, H.: 1995, Formation of magnetic shear and an electric current system in an emerging flux region. A&A 304, 541. ADS.

- Zhang, Cheng, and Ding (2012) Zhang, J., Cheng, X., Ding, M.-D.: 2012, Observation of an evolving magnetic flux rope before and during a solar eruption. Nature Communications 3, 747. DOI. ADS.

- Zirin (1988) Zirin, H.: 1988, Astrophysics of the sun. ADS.

- Zuccarello, F. et al. (2009) Zuccarello, F., Romano, P., Farnik, F., Karlicky, M., Contarino, L., Battiato, V., Guglielmino, S. L., Comparato, M., Ugarte-Urra, I.: 2009, The X17.2 flare occurred in NOAA 10486: an example of filament destabilization caused by a domino effect. A&A 493(2), 629. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:200809887.