GraphPrompt: Unifying Pre-Training and Downstream Tasks

for Graph Neural Networks

Abstract.

Graphs can model complex relationships between objects, enabling a myriad of Web applications such as online page/article classification and social recommendation. While graph neural networks (GNNs) have emerged as a powerful tool for graph representation learning, in an end-to-end supervised setting, their performance heavily relies on a large amount of task-specific supervision. To reduce labeling requirement, the “pre-train, fine-tune” and “pre-train, prompt” paradigms have become increasingly common. In particular, prompting is a popular alternative to fine-tuning in natural language processing, which is designed to narrow the gap between pre-training and downstream objectives in a task-specific manner. However, existing study of prompting on graphs is still limited, lacking a universal treatment to appeal to different downstream tasks. In this paper, we propose GraphPrompt, a novel pre-training and prompting framework on graphs. GraphPrompt not only unifies pre-training and downstream tasks into a common task template, but also employs a learnable prompt to assist a downstream task in locating the most relevant knowledge from the pre-trained model in a task-specific manner. Finally, we conduct extensive experiments on five public datasets to evaluate and analyze GraphPrompt.

†Corresponding authors.

1. Introduction

The ubiquitous Web is becoming the ultimate data repository, capable of linking a broad spectrum of objects to form gigantic and complex graphs. The prevalence of graph data enables a series of downstream tasks for Web applications, ranging from online page/article classification to friend recommendation in social networks. Modern approaches for graph analysis generally resort to graph representation learning including graph embedding and graph neural networks (GNNs). Earlier graph embedding approaches (Perozzi et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2015; Grover and Leskovec, 2016) usually embed nodes on the graph into a low-dimensional space, in which the structural information such as the proximity between nodes can be captured (Cai et al., 2018). More recently, GNNs (Kipf and Welling, 2017; Hamilton et al., 2017; Veličković et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019) have emerged as the state of the art for graph representation learning. Their key idea boils down to a message-passing framework, in which each node derives its representation by receiving and aggregating messages from its neighboring nodes recursively (Wu et al., 2020).

Graph pre-training. Typically, GNNs work in an end-to-end manner, and their performance depends heavily on the availability of large-scale, task-specific labeled data as supervision. This supervised paradigm presents two problems. First, task-specific supervision is often difficult or costly to obtain. Second, to deal with a new task, the weights of GNN models need to be retrained from scratch, even if the task is on the same graph. To address these issues, pre-training GNNs (Hu et al., 2020a, b; Qiu et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2021) has become increasingly popular, inspired by pre-training techniques in language and vision applications (Dong et al., 2019; Bao et al., 2022). The pre-training of GNNs leverages self-supervised learning on more readily available label-free graphs (i.e., graphs without task-specific labels), and learns intrinsic graph properties that intend to be general across tasks and graphs in a domain. In other words, the pre-training extracts a task-agnostic prior, and can be used to initialize model weights for a new task. Subsequently, the initial weights can be quickly updated through a lightweight fine-tuning step on a smaller number of task-specific labels.

However, the “pre-train, fine-tune” paradigm suffers from the problem of inconsistent objectives between pre-training and downstream tasks, resulting in suboptimal performance (Liu et al., 2021d). On one hand, the pre-training step aims to preserve various intrinsic graph properties such as node/edge features (Hu et al., 2020b, a), node connectivity/links (Hamilton et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2020a; Lu et al., 2021), and local/global patterns (Qiu et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2020b; Lu et al., 2021). On the other hand, the fine-tuning step aims to reduce the task loss, i.e., to fit the ground truth of the downstream task. The discrepancy between the two steps can be quite large. For example, pre-training may focus on learning the connectivity pattern between two nodes (i.e., related to link prediction), whereas fine-tuning could be dealing with a node or graph property (i.e., node classification or graph classification task).

Prior work. To narrow the gap between pre-training and downstream tasks, prompting (Brown et al., 2020) has first been proposed for language models, which is a natural language instruction designed for a specific downstream task to “prompt out” the semantic relevance between the task and the language model. Meanwhile, the parameters of the pre-trained language model are frozen without any fine-tuning, as the prompt can “pull” the task toward the pre-trained model. Thus, prompting is also more efficient than fine-tuning, especially when the pre-trained model is huge. Recently, prompting has also been introduced to graph pre-training in the GPPT approach (Sun et al., 2022). While the pioneering work has proposed a sophisticated design of pre-training and prompting, it can only be employed for the node classification task, lacking a universal treatment that appeals to different downstream tasks such as both node classification and graph classification.

Research problem and challenges. To address the divergence between graph pre-training and various downstream tasks, in this paper we investigate the design of pre-training and prompting for graph neural networks. In particular, we aim for a unified design that can suit different downstream tasks flexibly. This problem is non-trivial due to the following two challenges.

Firstly, to enable effective knowledge transfer from the pre-training to a downstream task, it is desirable that the pre-training step preserves graph properties that are compatible with the given task. However, since different downstream tasks often have different objectives, how do we unify pre-training with various downstream tasks on graphs, so that a single pre-trained model can universally support different tasks? That is, we try to convert the pre-training task and downstream tasks to follow the same “template”. Using pre-trained language models as an analogy, both their pre-training and downstream tasks can be formulated as masked language modeling.

Secondly, under the unification framework, it is still important to identify the distinction between different downstream tasks, in order to attain task-specific optima. For pre-trained language models, prompts in the form of natural language tokens or learnable word vectors have been designed to give different hints to different tasks, but it is less apparent what form prompts on graphs should take. Hence, how do we design prompts on graphs, so that they can guide different downstream tasks to effectively make use of the pre-trained model?

Present work. To address these challenges, we propose a novel graph pre-training and prompting framework, called GraphPrompt, aiming to unify the pre-training and downstream tasks for GNNs. Drawing inspiration from the prompting strategy for pre-trained language models, GraphPrompt capitalizes on a unified template to define the objectives for both pre-training and downstream tasks, thus bridging their gap. We further equip GraphPrompt with task-specific learnable prompts, which guides the downstream task to exploit relevant knowledge from the pre-trained GNN model. The unified approach endows GraphPrompt with the ability of working on limited supervision such as few-shot learning tasks.

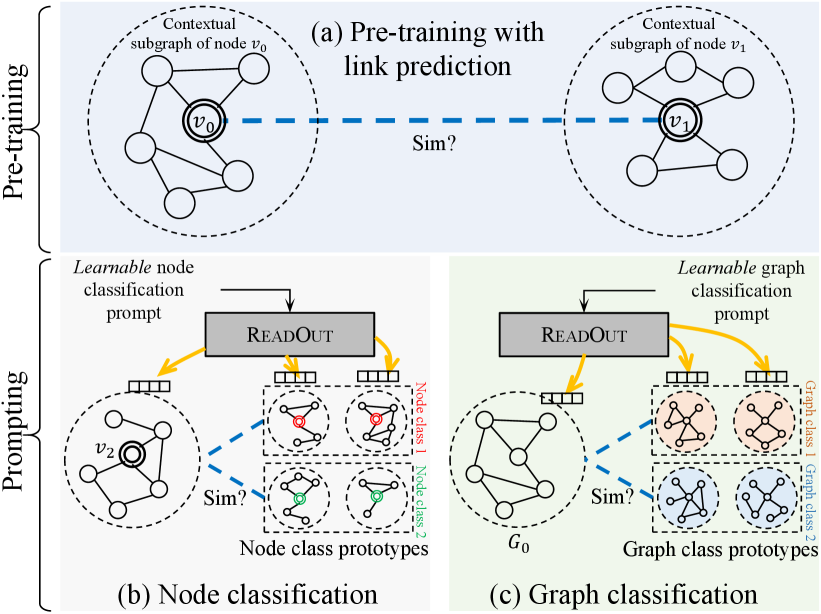

More specifically, to address the first challenge of unification, we focus on graph topology, which is a key enabler of graph models. In particular, subgraph is a universal structure that can be leveraged for both node- and graph-level tasks. At the node level, the information of a node can be enriched and represented by its contextual subgraph, i.e., a subgraph where the node resides in (Zhang and Chen, 2018; Huang and Zitnik, 2020); at the graph level, the information of a graph is naturally represented by the maximum subgraph (i.e., the graph itself). Consequently, we unify both the node- and graph-level tasks, whether in pre-training or downstream, into the same template: the similarity calculation of (sub)graph111As a graph is a subgraph of itself, we may simply use subgraph to refer to a graph too. representations. In this work, we adopt link prediction as the self-supervised pre-training task, given that links are readily available in any graph without additional annotation cost. Meanwhile, we focus on the popular node classification and graph classification as downstream tasks, which are node- and graph-level tasks, respectively. All these tasks can be cast as instances of learning subgraph similarity. On one hand, the link prediction task in pre-training boils down to the similarity between the contextual subgraphs of two nodes, as shown in Fig. 1(a). On the other hand, the downstream node or graph classification task boils down to the similarity between the target instance (a node’s contextual subgraph or the whole graph, resp.) and the class prototypical subgraphs constructed from labeled data, as illustrated in Figs. 1(b) and (c). The unified template bridges the gap between the pre-training and different downstream tasks.

Toward the second challenge, we distinguish different downstream tasks by way of the ReadOut operation on subgraphs. The ReadOut operation is essentially an aggregation function to fuse node representations in the subgraph into a single subgraph representation. For instance, sum pooling, which sums the representations of all nodes in the subgraph, is a practical and popular scheme for ReadOut. However, different downstream tasks can benefit from different aggregation schemes for their ReadOut. In particular, node classification tends to focus on features that can contribute to the representation of the target node, while graph classification tends to focus on features associated with the graph class. Motivated by such differences, we propose a novel task-specific learnable prompt to guide the ReadOut operation of each downstream task with an appropriate aggregation scheme. As shown in Fig. 1, the learnable prompt serves as the parameters of the ReadOut operation of downstream tasks, and thus enables different aggregation functions on the subgraphs of different tasks. Hence, GraphPrompt not only unifies the pre-training and downstream tasks into the same template based on subgraph similarity, but also recognizes the differences between various downstream tasks to guide task-specific objectives.

Contributions. To summarize, our contributions are three-fold. (1) We recognize the gap between graph pre-training and downstream tasks, and propose a unification framework GraphPrompt based on subgraph similarity for both pre-training and downstream tasks, including both node and graph classification tasks. (2) We propose a novel prompting strategy for GraphPrompt, hinging on a learnable prompt to actively guide downstream tasks using task-specific aggregation in ReadOut, in order to drive the downstream tasks to exploit the pre-trained model in a task-specific manner. (3) We conduct extensive experiments on five public datasets, and the results demonstrate the superior performance of GraphPrompt in comparison to the state-of-the-art approaches.

2. Related Work

Graph representation learning. The rise of graph representation learning, including earlier graph embedding (Perozzi et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2015; Grover and Leskovec, 2016) and recent GNNs (Kipf and Welling, 2017; Hamilton et al., 2017; Veličković et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019), opens up great opportunities for various downstream tasks at node and graph levels. Note that learning graph-level representations requires an additional ReadOut operation which summarizes the global information of a graph by aggregating node representations through a flat (Duvenaud et al., 2015; Gilmer et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019) or hierarchical (Gao and Ji, 2019; Lee et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2019; Ying et al., 2018) pooling algorithm. We refer the readers to two comprehensive surveys (Cai et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2020) for more details.

Graph pre-training. Inspired by the application of pre-training models in language (Dong et al., 2019; Beltagy et al., 2019) and vision (Lu et al., 2019; Bao et al., 2022) domains, graph pre-training (Xia et al., 2022) emerges as a powerful paradigm that leverages self-supervision on label-free graphs to learn intrinsic graph properties. While the pre-training learns a task-agnostic prior, a relatively light-weight fine-tuning step is further employed to update the pre-trained weights to fit a given downstream task. Different pre-training approaches design different self-supervised tasks based on various graph properties such as node features (Hu et al., 2020b, a), links (Kipf and Welling, 2016; Hamilton et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2020a; Lu et al., 2021), local or global patterns (Qiu et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2020b; Lu et al., 2021), local-global consistency (Velickovic et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020a; Peng et al., 2020; Hassani and Khasahmadi, 2020), and their combinations (You et al., 2020, 2021; Suresh et al., 2021).

However, the above approaches do not consider the gap between pre-training and downstream objectives, which limits their generalization ability to handle different tasks. Some recent studies recognize the importance of narrowing this gap. L2P-GNN (Lu et al., 2021) capitalizes on meta-learning (Finn et al., 2017) to simulate the fine-tuning step during pre-training. However, since the downstream tasks can still differ from the simulation task, the problem is not fundamentally addressed. In other fields, as an alternative to fine-tuning, researchers turn to prompting (Brown et al., 2020), in which a task-specific prompt is used to cue the downstream tasks. Prompts can be either handcrafted (Brown et al., 2020) or learnable (Liu et al., 2021e; Lester et al., 2021). On graph data, the study of prompting is still limited. One recent work called GPPT (Sun et al., 2022) capitalizes on a sophisticated design of learnable prompts on graphs, but it only works with node classification, lacking a unification effort to accommodate other downstream tasks like graph classification. Besides, there is a model also named as GraphPrompt (Zhang et al., 2021), but it considers an NLP task (biomedical entity normalization) on text data, where graph is only auxiliary. It employs the standard text prompt unified by masked language modeling, assisted by a relational graph to generate text templates, which is distinct from our work.

Comparison to other settings. Our few-shot setting is different from other paradigms that also deal with label scarcity, including semi-supervised learning (Kipf and Welling, 2017) and meta-learning (Finn et al., 2017). In particular, semi-supervised learning cannot cope with novel classes not seen in training, while meta-learning requires a large volume of labeled data in their base classes for a meta-training phase, before they can handle few-shot tasks in testing.

3. Preliminaries

In this section, we give the problem definition and introduce the background of GNNs.

3.1. Problem Definition

Graph. A graph can be defined as , where is the set of nodes and is the set of edges. We also assume an input feature matrix of the nodes, , is available. Let denote the feature vector of node . In addition, we denote a set of graphs as .

Problem. In this paper, we investigate the problem of graph pre-training and prompting. For the downstream tasks, we consider the popular node classification and graph classification tasks. For node classification on a graph , let be the set of node classes with denoting the class label of node . For graph classification on a set of graphs , let be the set of graph labels with denoting the class label of graph .

In particular, the downstream tasks are given limited supervision in a few-shot setting: for each class in the two tasks, only labeled samples (i.e., nodes or graphs) are provided, known as -shot classification.

3.2. Graph Neural Networks

The success of GNNs boils down to the message-passing mechanism (Wu et al., 2020), in which each node receives and aggregates messages (i.e., features or embeddings) from its neighboring nodes to generate its own representation. This operation of neighborhood aggregation can be stacked in multiple layers to enable recursive message passing. Formally, in the -th GNN layer, the embedding of node , denoted by , is calculated based on the embeddings in the previous layer, as follows.

| (1) |

where is the set of neighboring nodes of , is the learnable GNN parameters in layer . is the neighborhood aggregation function and can take various forms, ranging from the simple mean pooling (Kipf and Welling, 2017; Hamilton et al., 2017) to advanced neural networks such as neural attention (Veličković et al., 2018) or multi-layer perceptrons (Xu et al., 2019). Note that in the first layer, the input node embedding can be initialized as the node features in . The total learnable GNN parameters can be denoted as . For brevity, we simply denote the output node representations of the last layer as .

4. Proposed Approach

In this section, we present our proposed approach GraphPrompt.

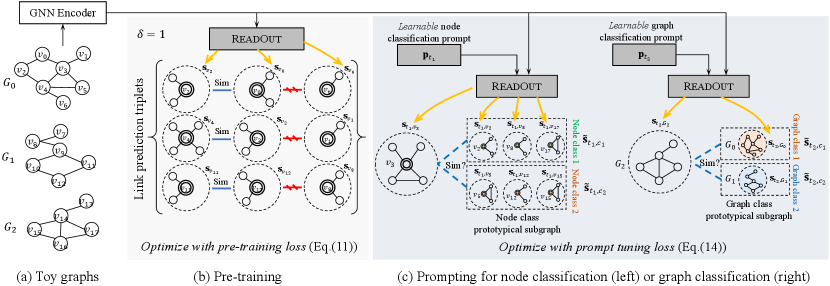

4.1. Unification Framework

We first introduce the overall framework of GraphPrompt in Fig. 2. Our framework is deployed on a set of label-free graphs shown in Fig. 2(a), for pre-training in Fig. 2(b). The pre-training adopts a link prediction task, which is self-supervised without requiring extra annotation. Afterward, in Fig. 2(c), we capitalize on a learnable prompt to guide each downstream task, namely, node classification or graph classification, for task-specific exploitation of the pre-trained model. In the following, we explain how the framework supports a unified view of pre-training and downstream tasks.

Instances as subgraphs. The key to the unification of pre-training and downstream tasks lies in finding a common template for the tasks. The task-specific prompt can then be further fused with the template of each downstream task, to distinguish the varying characteristics of different tasks.

In comparison to other fields such as visual and language processing, graph learning is uniquely characterized by the exploitation of graph topology. In particular, subgraph is a universal structure capable of expressing both node- and graph-level instances. On one hand, at the node level, every node resides in a local neighborhood, which in turn contextualizes the node (Liu et al., 2020, 2021a, 2021c). The local neighborhood of a node on a graph is usually defined by a contextual subgraph , where its set of nodes and edges are respectively given by

| (2) | ||||

| (3) |

where gives the shortest distance between nodes and on the graph , and is a predetermined threshold. That is, consists of nodes within hops from the node , and the edges between those nodes. Thus, the contextual subgraph embodies not only the self-information of the node , but also rich contextual information to complement the self-information (Zhang and Chen, 2018; Huang and Zitnik, 2020). On the other hand, at the graph level, the maximum subgraph of a graph , denoted , is the graph itself, i.e., . The maximum subgraph spontaneously embodies all information of . In summary, subgraphs can be used to represent both node- and graph-level instances: Given an instance which can either be a node or a graph (e.g., or ), the subgraph offers a unified access to the information associated with .

Unified task template. Based on the above subgraph definitions for both node- and graph-level instances, we are ready to unify different tasks to follow a common template. Specifically, the link prediction task in pre-training and the downstream node and graph classification tasks can all be redefined as subgraph similarity learning. Let be the vector representation of the subgraph , and be the cosine similarity function. As illustrated in Figs. 2(b) and (c), the three tasks can be mapped to the computation of subgraph similarity, which is formalized below.

-

•

Link prediction: This is a node-level task. Given a graph and a triplet of nodes such that and , we shall have

(4) Intuitively, the contextual subgraph of shall be more similar to that of a node linked to than that of another unlinked node.

-

•

Node classification: This is also a node-level task. Consider a graph with a set of node classes , and a set of labeled nodes where and is the corresponding label of . As we adopt a -shot setting, there are exactly pairs of for every class . For each class , further define a node class prototypical subgraph represented by a vector , given by

(5) Note that the class prototypical subgraph is a “virtual” subgraph with a latent representation in the same embedding space as the node contextual subgraphs. Basically, it is constructed as the mean representation of the contextual subgraphs of labeled nodes in a given class. Then, given a node not in the labeled set , its class label shall be

(6) Intuitively, a node shall belong to the class whose prototypical subgraph is the most similar to the node’s contextual subgraph.

-

•

Graph classification: This is a graph-level task. Consider a set of graphs with a set of graph classes , and a set of labeled graphs where and is the corresponding label of . In the -shot setting, there are exactly pairs of for every class . Similar to node classification, for each class , we define a graph class prototypical subgraph, also represented by the mean embedding vector of the (sub)graphs in :

(7) Then, given a graph not in the labeled set , its class label shall be

(8) Intuitively, a graph shall belong to the class whose prototypical subgraph is the most similar to itself. ∎

It is worth noting that node and graph classification can be further condensed into a single set of notations. Let be an annotated instance of graph data, i.e., is either a node or a graph, and is the class label of among the set of classes . Then,

| (9) |

Finally, to materialize the common task template, we discuss how to learn the subgraph embedding vector for the subgraph . Given node representations generated by a GNN (see Sect. 3.2), a standard approach of computing is to employ a ReadOut operation that aggregates the representations of nodes in the subgraph . That is,

| (10) |

The choice of the aggregation scheme for ReadOut is flexible, including sum pooling and more advanced techniques (Ying et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019). In our implementation, we simply use sum pooling.

In summary, the unification framework is enabled by the common task template of subgraph similarity learning, which lays the foundation of our pre-training and prompting strategies as we will introduce in the following parts.

4.2. Pre-Training Phase

As discussed earlier, our pre-training phase employs the link prediction task. Using link prediction/generation is a popular and natural way (Hamilton et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2020a; Hwang et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2021), as a vast number of links are readily available on large-scale graph data without extra annotation. In other words, the link prediction objective can be optimized on label-free graphs, such as those shown in Fig. 2(a), in a self-supervised manner.

Based on the common template defined in Sect. 4.1, the link prediction task is anchored on the similarity of the contextual subgraphs of two candidate nodes. Generally, the subgraphs of two positive (i.e., linked) candidates shall be more similar than those of negative (i.e., non-linked) candidates, as illustrated in Fig. 2(b). Subsequently, the pre-trained prior on subgraph similarity can be naturally transferred to node classification downstream, which shares a similar intuition: the subgraphs of nodes in the same class shall be more similar than those of nodes from different classes. On the other hand, the prior can also support graph classification downstream, as graph similarity is consistent with subgraph similarity not only in letter (as a graph is technically always a subgraph of itself), but also in spirit. The “spirit” here refers to the tendency that graphs sharing similar subgraphs are likely to be similar themselves, which means graph similarity can be translated into the similarity of the containing subgraphs (Shervashidze et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2018; Togninalli et al., 2019).

Formally, given a node on graph , we randomly sample one positive node from ’s neighbors, and a negative node from the graph that does not link to , forming a triplet . Our objective is to increase the similarity between the contextual subgraphs and , while decreasing that between and . More generally, on a set of label-free graphs , we sample a number of triplets from each graph to construct an overall training set . Then, we define the following pre-training loss.

| (11) |

where is a temperature hyperparameter to control the shape of the output distribution. Note that the loss is parameterized by , which represents the GNN model weights.

The output of the pre-training phase is the optimal model parameters . can be used to initialize the GNN weights for downstream tasks, thus enabling the transfer of prior knowledge downstream.

4.3. Prompting for Downstream Tasks

The unification of pre-training and downstream tasks enables more effective knowledge transfer as the tasks in the two phases are made more compatible by following a common template. However, it is still important to distinguish different downstream tasks, in order to capture task individuality and achieve task-specific optimum.

To cope with this challenge, we propose a novel task-specific learnable prompt on graphs, inspired by prompting in natural language processing (Brown et al., 2020). In language contexts, a prompt is initially a handcrafted instruction to guide the downstream task, which provides task-specific cues to extract relevant prior knowledge through a unified task template (typically, pre-training and downstream tasks are all mapped to masked language modeling). More recently, learnable prompts (Liu et al., 2021e; Lester et al., 2021) have been proposed as an alternative to handcrafted prompts, to alleviate the high engineering cost of the latter.

Prompt design. Nevertheless, our proposal is distinctive from language-based prompting for two reasons. Firstly, we have a different task template from masked language modeling. Secondly, since our prompts are designed for graph structures, they are more abstract and cannot take the form of language-based instructions. Thus, they are virtually impossible to be handcrafted. Instead, they should be topology related to align with the core of graph learning. In particular, under the same task template of subgraph similarity learning, the ReadOut operation (used to generate the subgraph representation) can be “prompted” differently for different downstream tasks. Intuitively, different tasks can benefit from different aggregation schemes for their ReadOut. For instance, node classification pays more attention to features that are topically more relevant to the target node. In contrast, graph classification tends to focus on features that are correlated to the graph class. Moreover, the important features may also vary given different sets of instances or classes in a task.

Formally, let denote a learnable prompt vector for a downstream task , as shown in Fig. 2(c). The prompt-assisted ReadOut operation on a subgraph for task is

| (12) |

where is the task -specific subgraph representation, and denotes the element-wise multiplication. That is, we perform a feature weighted summation of the node representations from the subgraph, where the prompt vector is a dimension-wise reweighting in order to extract the most relevant prior knowledge for the task .

Note that other prompt designs are also possible. For example, we could consider a learnable prompt matrix , which applies a linear transformation to the node representations:

| (13) |

More complex prompts such as an attention layer is another alternative. However, one of the main motivation of prompting instead of fine-tuning is to reduce reliance on labeled data. In few-shot settings, given very limited supervision, prompts with fewer parameters are preferred to mitigate the risk of overfitting. Hence, the feature weighting scheme in Eq. (12) is adopted for our prompting as the prompt is a single vector of the same length as the node representation, which is typically a small number (e.g., 128).

Prompt tuning. To optimize the learnable prompt, also known as prompt tuning, we formulate the loss based on the common template of subgraph similarity, using the prompt-assisted task-specific subgraph representations.

Formally, consider a task with a labeled training set , where is an instance (i.e., a node or a graph), and is the class label of among the set of classes . The loss for prompt tuning is defined as

| (14) |

where the class prototypical subgraph for class is represented by , which is also generated by the prompt-assisted, task-specific ReadOut.

Note that, the prompt tuning loss is only parameterized by the learnable prompt vector , without the GNN weights. Instead, the pre-trained GNN weights are frozen for downstream tasks, as no fine-tuning is necessary. This significantly decreases the number of parameters to be updated downstream, thus not only improving the computational efficiency of task learning and inference, but also reducing the reliance on labeled data.

5. Experiments

In this section, we conduct extensive experiments including node classification and graph classification as downstream tasks on five benchmark datasets to evaluate the proposed GraphPrompt.

5.1. Experimental Setup

Datasets. We employ five benchmark datasets for evaluation. (1) Flickr (Wen et al., 2021) is an image sharing network. (2) PROTEINS (Borgwardt et al., 2005) is a collection of protein graphs which include the amino acid sequence, conformation, structure, and features such as active sites of the proteins. (3) COX2 (Rossi and Ahmed, [n. d.]) is a dataset of molecular structures including 467 cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. (4) ENZYMES (Wang et al., 2022) is a dataset of 600 enzymes collected from the BRENDA enzyme database. (5) BZR (Rossi and Ahmed, [n. d.]) is a collection of 405 ligands for benzodiazepine receptor.

We summarize these datasets in Table 1, and present further details in Appendix B. Note that the “Task” column indicates the type of downstream task performed on each dataset: “N” for node classification and “G” for graph classification.

| Graphs | Graph classes | Avg. nodes | Avg. edges | Node features | Node classes | Task (N/G) | |

| Flickr | 1 | - | 89,250 | 899,756 | 500 | 7 | N |

| PROTEINS | 1,113 | 2 | 39.06 | 72.82 | 1 | 3 | N, G |

| COX2 | 467 | 2 | 41.22 | 43.45 | 3 | - | G |

| ENZYMES | 600 | 6 | 32.63 | 62.14 | 18 | 3 | N, G |

| BZR | 405 | 2 | 35.75 | 38.36 | 3 | - | G |

Baselines. We evaluate GraphPrompt against the state-of-the-art approaches from three main categories, as follows. (1) End-to-end graph neural networks: GCN (Kipf and Welling, 2017), GraphSAGE (Hamilton et al., 2017), GAT (Veličković et al., 2018) and GIN (Xu et al., 2019). They capitalize on the key operation of neighborhood aggregation to recursively aggregate messages from the neighbors, and work in an end-to-end manner. (2) Graph pre-training models: DGI (Velickovic et al., 2019), InfoGraph (Sun et al., 2020b), and GraphCL (You et al., 2020). They work in the “pre-train, fine-tune” paradigm. In particular, they pre-train the GNN models to preserve the intrinsic graph properties, and fine-tune the pre-trained weights on downstream tasks to fit task labels. (3) Graph prompt models: GPPT (Sun et al., 2022). GPPT utilizes a link prediction task for pre-training, and resorts to a learnable prompt for the node classification task, which is mapped to a link prediction task.

Note that other few-shot learning methods on graphs, such as Meta-GNN (Zhou et al., 2019) and RALE (Liu et al., 2021b), adopt a meta-learning paradigm (Finn et al., 2017). Thus, they cannot be used in our setting, as they require labeled data in their base classes for the meta-training phase. In our approach, only label-free graphs are utilized for pre-training.

Settings and parameters. To evaluate the goal of our GraphPrompt in realizing a unified design that can suit different downstream tasks flexibly, we consider two typical types of downstream tasks, i.e., node classification and graph classification. In particular, for the datasets which are suitable for both of these two tasks, i.e., PROTEINS and ENZYMES, we only pre-train the GNN model once on each dataset, and utilize the same pre-trained model for the two downstream tasks with their task-specific prompting.

The downstream tasks follow a -shot classification setting. For each type of downstream task, we construct a series of -shot classification tasks. The details of task construction will be elaborated later when reporting the results in Sect. 5.2. For task evaluation, as the -shot tasks are balanced classification, we employ accuracy as the evaluation metric following earlier work (Wang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021b).

For all the baselines, based on the authors’ code and default settings, we further tune their hyper-parameters to optimize their performance. We present more implementation details of the baselines and our GraphPrompt in Appendix D.

5.2. Performance Evaluation

As discussed, we perform two types of downstream task different from the link prediction task in pre-training, namely, node classification and graph classification in few-shot settings. We first evaluate on a fixed-shot setting, and then vary the shot numbers to see the performance trend.

Few-shot node classification. We conduct this node-level task on three datasets, i.e., Flickr, PROTEINS, and ENZYMES. Following a typical -shot setup (Zhou et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021b), we generate a series of few-shot tasks for model training and validation. In particular, for PROTEINS and ENZYMES, on each graph we randomly generate ten 1-shot node classification tasks (i.e., in each task, we randomly sample 1 node per class) for training and validation, respectively. Each training task is paired with a validation task, and the remaining nodes not sampled by the pair of training and validation tasks will be used for testing. For Flickr, as it contains a large number of very sparse node features, selecting very few shots for training may result in inferior performance for all the methods. Therefore, we randomly generate ten 50-shot node classifcation tasks, for training and validation, respectively. On Flickr, 50 shots are still considered few, accounting for less than 0.06% of all nodes on the graph.

Table 2 illustrates the results of few-shot node classification. We have the following observations. First, our proposed GraphPrompt outperforms all the baselines across the three datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness of GraphPrompt in transferring knowledge from the pre-training to downstream tasks. In particular, by virtue of the unification framework and prompt-based task-specific aggregation in ReadOut function, GraphPrompt is able to narrow the gap between pre-training and downstream tasks, and guide the downstream tasks to exploit the pre-trained model in a task-specific manner. Second, compared to graph pre-training models, end-to-end GNN models can sometimes achieve comparable or even better performance. This implies that the discrepancy between the pre-training and downstream tasks in these pre-training approaches obstructs the knowledge transfer from the former to the latter. In such a case, even with sophisticated pre-training, they cannot effectively promote the performance of downstream tasks. Third, the graph prompt model GPPT is only comparable to or even worse than the other baselines, despite also using prompts. A potential reason is that GPPT requires much more learnable parameters in their prompts than ours, which may not work well given very few shots (e.g., 1-shot).

Few-shot graph classification. We further conduct few-shot graph classification on four datasets, i.e., PROTEINS, COX2, ENZYMES, and BZR. For each dataset, we randomly generate 100 5-shot classification tasks for training and validation, following a similar process for node classification tasks.

We illustrate the results of few-shot graph classification in Table 3, and have the following observations. First, our proposed GraphPrompt significantly outperforms the baselines on these four datasets. This again demonstrates the necessity of unification for pre-training and downstream tasks, and the effectiveness of prompt-assisted task-specific aggregation for ReadOut. Second, as both node and graph classification tasks share the same pre-trained model on PROTEINS and ENZYMES, the superior performance of GraphPrompt on both types of task further demonstrates that, the gap between different tasks is well addressed by virtue of our unification framework. Third, the graph pre-training models generally achieve better performance than the end-to-end GNN models. This is because both InfoGraph and GraphCL capitalize on graph-level tasks for pre-training, which are naturally closer to the downstream graph classification.

All tabular results are in percent, with best bolded and runner-up underlined.

Methods

Flickr

PROTEINS

ENZYMES

50-shot

1-shot

1-shot

GCN

9.22 9.49

59.60 12.44

61.49 12.87

GraphSAGE

13.52 11.28

59.12 12.14

61.81 13.19

GAT

16.02 12.72

58.14 12.05

60.77 13.21

GIN

10.18 5.41

60.53 12.19

63.81 11.28

DGI

17.71 1.09

54.92 18.46

63.33 18.13

GraphCL

18.37 1.72

52.00 15.83

58.73 16.47

GPPT

18.95 1.92

50.83 16.56

53.79 17.46

GraphPrompt

20.21 11.52

63.03 12.14

67.04 11.48

| Methods | PROTEINS | COX2 | ENZYMES | BZR |

| 5-shot | 5-shot | 5-shot | 5-shot | |

| GCN | 54.87 11.20 | 51.37 11.06 | 20.37 5.24 | 56.16 11.07 |

| GraphSAGE | 52.99 10.57 | 52.87 11.46 | 18.31 6.22 | 57.23 10.95 |

| GAT | 48.78 18.46 | 51.20 27.93 | 15.90 4.13 | 53.19 20.61 |

| GIN | 58.17 8.58 | 51.89 8.71 | 20.34 5.01 | 57.45 10.54 |

| InfoGraph | 54.12 8.20 | 54.04 9.45 | 20.90 3.32 | 57.57 9.93 |

| GraphCL | 56.38 7.24 | 55.40 12.04 | 28.11 4.00 | 59.22 7.42 |

| GraphPrompt | 64.42 4.37 | 59.21 6.82 | 31.45 4.32 | 61.63 7.68 |

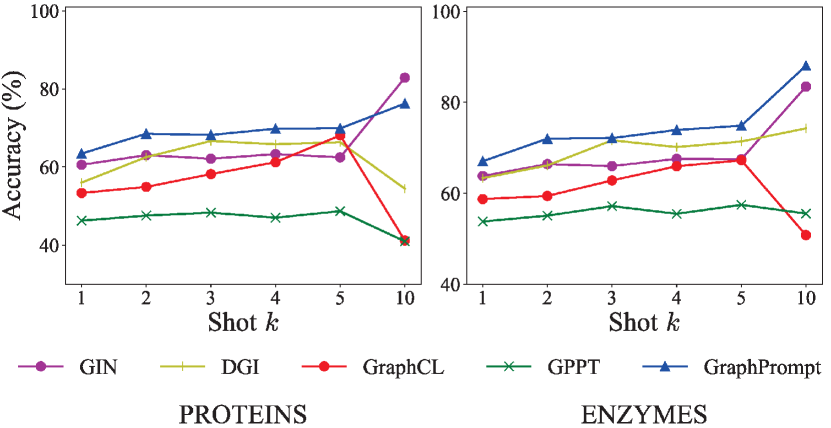

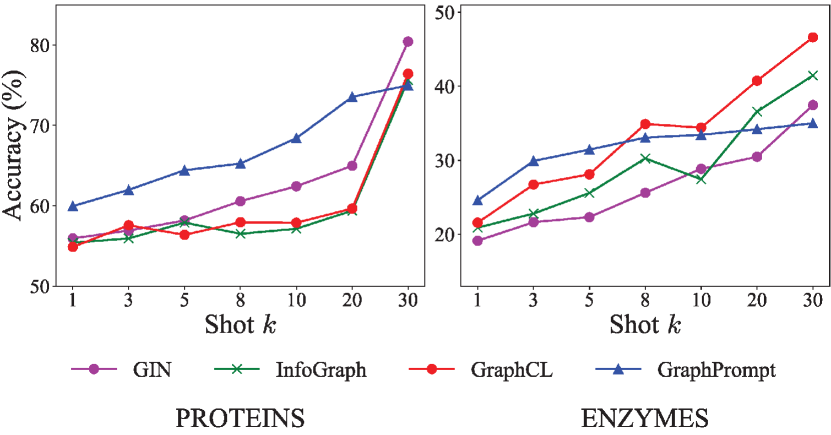

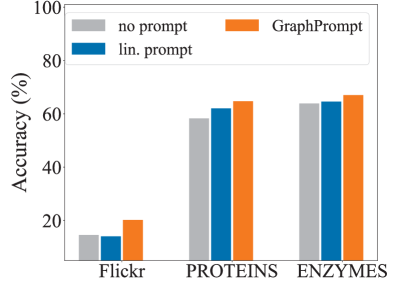

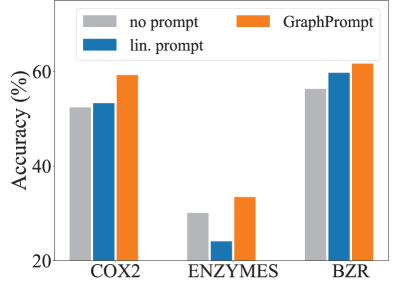

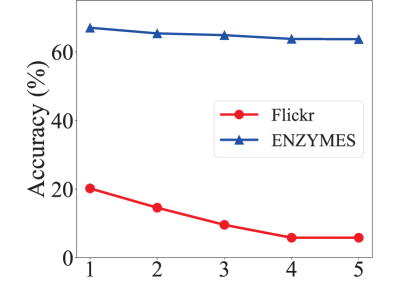

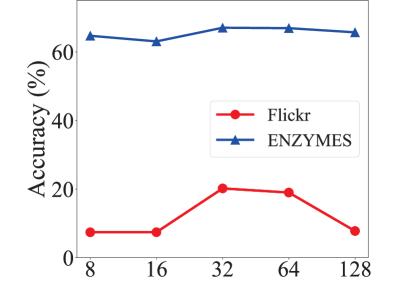

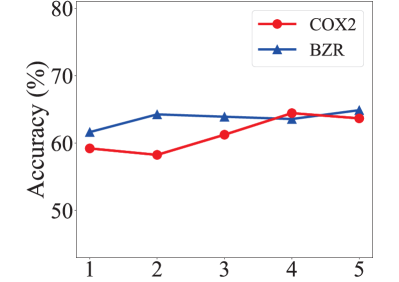

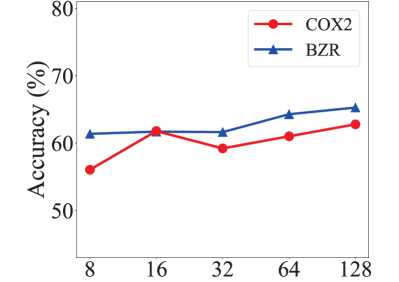

Performance with different shots. We study the impact of number of shots on the PROTEINS and ENZYMES datasets. For node classification, we vary the number of shots between 1 and 10, and compare with several competitive baselines (i.e., GIN, DGI, GraphCL, and GPPT) in Fig. 3. For few-shot graph classification, we vary the number of shots between 1 and 30, and compare with competitive baselines (i.e., GIN, InfoGraph, and GraphCL) in Fig. 4. The task settings are identical to those stated earlier.

In general, our proposed GraphPrompt consistently outperforms the baselines especially with lower shots. For node classification, as the number of nodes in each graph is relatively small, 10 shots per class might be sufficient for semi-supervised node classification. Nevertheless, GraphPrompt is competitive even with 10 shots. For graph classification, GraphPrompt can be surpassed by some baselines when given more shots (e.g., 20 or more), especially on ENZYMES. On this dataset, 30 shots per class implies 30% of the 600 graphs are used for training, which is not our target scenario.

5.3. Model Analysis

We further analyse several aspects of our model. Due to space constraint, we only report the ablation and parameter efficiency study, and leave the rest to Appendix E.

Ablation study. To evaluate the contribution of each component, we conduct an ablation study by comparing GraphPrompt with different prompting strategies: (1) no prompt: for downstream tasks, we remove the prompt vector, and conduct classification by employing a classifier on the subgraph representations obtained by a direct sum-based ReadOut. (2) lin. prompt: we replace the prompt vector with a linear transformation matrix in Eq. (13).

We conduct the ablation study on three datasets for node classification (Flickr, PROTEINS, and ENZYMES) and graph classification (COX2, ENZYMES, and BZR), respectively, and illustrate the comparison in Fig. 5. We have the following observations. (1) Without the prompt vector, no prompt usually performs the worst among the variants, showing the necessity of prompting the ReadOut operation differently for different downstream tasks. (2) Converting the prompt vector into a linear transformation matrix also hurts the performance, as the matrix involves more parameters thus increasing the reliance on labeled data.

Parameter efficiency. We also compare the number of parameters that needs to be updated in a downstream node classification task for a few representative models, as well as their number of floating point operations (FLOPs), in Table 4.

In particular, as GIN works in an end-to-end manner, it is obvious that it involves the largest number of parameters for updating. For GPPT, it requires a separate learnable vector for each class as its representation, and an attention module to weigh the neighbors for aggregation in the structure token generation. Therefore, GPPT needs to update more parameters than GraphPrompt, which is one factor that impairs its performance in downstream tasks. For our proposed GraphPrompt, it not only outperforms the baselines GIN and GPPT as we have seen earlier, but also requires the least parameters and FLOPs for downstream tasks. For illustration, in addition to prompt tuning, if we also fine-tune the pre-trained weights instead of freezing them (denoted GraphPrompt+ft), there will be significantly more parameters to update.

| Methods | Flickr | PROTEINS | ENZYMES | |||

| Params | FLOPs | Params | FLOPs | Params | FLOPs | |

| GIN | 22,183 | 240,100 | 5,730 | 12,380 | 6,280 | 11,030 |

| GPPT | 4,096 | 4,582 | 1,536 | 1,659 | 1,536 | 1,659 |

| GraphPrompt | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| GraphPrompt-ft | 21,600 | 235,200 | 6,176 | 13,440 | 6,176 | 10,944 |

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we studied the research problem of prompting on graphs and proposed GraphPrompt, in order to overcome the limitations of graph neural networks in the supervised or “pre-train, fine-tune” paradigms. In particular, to narrow the gap between pre-training and downstream objectives on graphs, we introduced a unification framework by mapping different tasks to a common task template. Moreover, to distinguish task individuality and achieve task-specific optima, we proposed a learnable task-specific prompt vector that guides each downstream task to make full of the pre-trained model. Finally, we conduct extensive experiments on five public datasets, and show that GraphPrompt significantly outperforms various state-of-the-art baselines.

Acknowledgments

This research / project is supported by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Academic Research Fund Tier 2 (MOE-T2EP20122-0041). Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Ministry of Education, Singapore.

References

- (1)

- Bao et al. (2022) Hangbo Bao, Li Dong, Songhao Piao, and Furu Wei. 2022. BEiT: BERT Pre-Training of Image Transformers. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Beltagy et al. (2019) Iz Beltagy, Kyle Lo, and Arman Cohan. 2019. SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text. In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing. 3615–3620.

- Borgwardt et al. (2005) Karsten M Borgwardt, Cheng Soon Ong, Stefan Schönauer, SVN Vishwanathan, Alex J Smola, and Hans-Peter Kriegel. 2005. Protein function prediction via graph kernels. Bioinformatics 21, suppl_1 (2005), i47–i56.

- Brown et al. (2020) Tom Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared D Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, et al. 2020. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020), 1877–1901.

- Cai et al. (2018) Hongyun Cai, Vincent W Zheng, and Kevin Chen-Chuan Chang. 2018. A comprehensive survey of graph embedding: Problems, techniques, and applications. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 30, 9 (2018), 1616–1637.

- Chen et al. (2020) Deli Chen, Yankai Lin, Wei Li, Peng Li, Jie Zhou, and Xu Sun. 2020. Measuring and relieving the over-smoothing problem for graph neural networks from the topological view. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 3438–3445.

- Dong et al. (2019) Li Dong, Nan Yang, Wenhui Wang, Furu Wei, Xiaodong Liu, Yu Wang, Jianfeng Gao, Ming Zhou, and Hsiao-Wuen Hon. 2019. Unified language model pre-training for natural language understanding and generation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (2019).

- Duvenaud et al. (2015) David K Duvenaud, Dougal Maclaurin, Jorge Iparraguirre, Rafael Bombarell, Timothy Hirzel, Alán Aspuru-Guzik, and Ryan P Adams. 2015. Convolutional networks on graphs for learning molecular fingerprints. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28 (2015).

- Finn et al. (2017) Chelsea Finn, Pieter Abbeel, and Sergey Levine. 2017. Model-agnostic meta-learning for fast adaptation of deep networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning. 1126–1135.

- Gao and Ji (2019) Hongyang Gao and Shuiwang Ji. 2019. Graph u-nets. In International Conference on Machine Learning. 2083–2092.

- Gilmer et al. (2017) Justin Gilmer, Samuel S Schoenholz, Patrick F Riley, Oriol Vinyals, and George E Dahl. 2017. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. In International Conference on Machine Learning. 1263–1272.

- Grover and Leskovec (2016) Aditya Grover and Jure Leskovec. 2016. node2vec: Scalable feature learning for networks. In ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 855–864.

- Hamilton et al. (2017) Will Hamilton, Zhitao Ying, and Jure Leskovec. 2017. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017), 1025–1035.

- Hassani and Khasahmadi (2020) Kaveh Hassani and Amir Hosein Khasahmadi. 2020. Contrastive multi-view representation learning on graphs. In International Conference on Machine Learning. 4116–4126.

- Hu et al. (2020b) Weihua Hu, Bowen Liu, Joseph Gomes, Marinka Zitnik, Percy Liang, Vijay Pande, and Jure Leskovec. 2020b. Strategies for Pre-training Graph Neural Networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Hu et al. (2020a) Ziniu Hu, Yuxiao Dong, Kuansan Wang, Kai-Wei Chang, and Yizhou Sun. 2020a. GPT-GNN: Generative pre-training of graph neural networks. In ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 1857–1867.

- Huang and Zitnik (2020) Kexin Huang and Marinka Zitnik. 2020. Graph meta learning via local subgraphs. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020), 5862–5874.

- Hwang et al. (2020) Dasol Hwang, Jinyoung Park, Sunyoung Kwon, KyungMin Kim, Jung-Woo Ha, and Hyunwoo J Kim. 2020. Self-supervised auxiliary learning with meta-paths for heterogeneous graphs. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020), 10294–10305.

- Kipf and Welling (2016) Thomas N Kipf and Max Welling. 2016. Variational graph auto-encoders. In Bayesian Deep Learning Workshop.

- Kipf and Welling (2017) Thomas N Kipf and Max Welling. 2017. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Lee et al. (2019) Junhyun Lee, Inyeop Lee, and Jaewoo Kang. 2019. Self-attention graph pooling. In International Conference on Machine Learning. 3734–3743.

- Lester et al. (2021) Brian Lester, Rami Al-Rfou, and Noah Constant. 2021. The Power of Scale for Parameter-Efficient Prompt Tuning. In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. 3045–3059.

- Liu et al. (2021d) Pengfei Liu, Weizhe Yuan, Jinlan Fu, Zhengbao Jiang, Hiroaki Hayashi, and Graham Neubig. 2021d. Pre-train, prompt, and predict: A systematic survey of prompting methods in natural language processing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.13586 (2021).

- Liu et al. (2021e) Xiao Liu, Yanan Zheng, Zhengxiao Du, Ming Ding, Yujie Qian, Zhilin Yang, and Jie Tang. 2021e. GPT understands, too. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.10385 (2021).

- Liu et al. (2021a) Zemin Liu, Yuan Fang, Chenghao Liu, and Steven C.H. Hoi. 2021a. Node-wise Localization of Graph Neural Networks. In International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 1520–1526.

- Liu et al. (2021b) Zemin Liu, Yuan Fang, Chenghao Liu, and Steven CH Hoi. 2021b. Relative and absolute location embedding for few-shot node classification on graph. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 4267–4275.

- Liu et al. (2021c) Zemin Liu, Trung-Kien Nguyen, and Yuan Fang. 2021c. Tail-GNN: Tail-Node Graph Neural Networks. In ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 1109–1119.

- Liu et al. (2020) Zemin Liu, Wentao Zhang, Yuan Fang, Xinming Zhang, and Steven C. H. Hoi. 2020. Towards Locality-Aware Meta-Learning of Tail Node Embeddings on Networks. In Conference on Information and Knowledge Management. 975–984.

- Lu et al. (2019) Jiasen Lu, Dhruv Batra, Devi Parikh, and Stefan Lee. 2019. ViLBERT: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolinguistic representations for vision-and-language tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (2019).

- Lu et al. (2021) Yuanfu Lu, Xunqiang Jiang, Yuan Fang, and Chuan Shi. 2021. Learning to pre-train graph neural networks. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 4276–4284.

- Ma et al. (2019) Yao Ma, Suhang Wang, Charu C Aggarwal, and Jiliang Tang. 2019. Graph convolutional networks with eigenpooling. In ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 723–731.

- Peng et al. (2020) Zhen Peng, Wenbing Huang, Minnan Luo, Qinghua Zheng, Yu Rong, Tingyang Xu, and Junzhou Huang. 2020. Graph representation learning via graphical mutual information maximization. In The Web Conference. 259–270.

- Perozzi et al. (2014) Bryan Perozzi, Rami Al-Rfou, and Steven Skiena. 2014. DeepWalk: Online learning of social representations. In ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 701–710.

- Qiu et al. (2020) Jiezhong Qiu, Qibin Chen, Yuxiao Dong, Jing Zhang, Hongxia Yang, Ming Ding, Kuansan Wang, and Jie Tang. 2020. GCC: Graph contrastive coding for graph neural network pre-training. In ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 1150–1160.

- Rossi and Ahmed ([n. d.]) Ryan A. Rossi and Nesreen K. Ahmed. [n. d.]. The Network Data Repository with Interactive Graph Analytics and Visualization. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 4292–4293.

- Shervashidze et al. (2011) Nino Shervashidze, Pascal Schweitzer, Erik Jan Van Leeuwen, Kurt Mehlhorn, and Karsten M Borgwardt. 2011. Weisfeiler-lehman graph kernels. Journal of Machine Learning Research 12, 9 (2011).

- Sun et al. (2020a) Fan-Yun Sun, Jordan Hoffman, Vikas Verma, and Jian Tang. 2020a. InfoGraph: Unsupervised and Semi-supervised Graph-Level Representation Learning via Mutual Information Maximization. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Sun et al. (2020b) Fan-Yun Sun, Jordan Hoffmann, Vikas Verma, and Jian Tang. 2020b. InfoGraph: Unsupervised and semi-supervised graph-level representation learning via mutual information maximization. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Sun et al. (2022) Mingchen Sun, Kaixiong Zhou, Xin He, Ying Wang, and Xin Wang. 2022. GPPT: Graph Pre-training and Prompt Tuning to Generalize Graph Neural Networks. In ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 1717–1727.

- Suresh et al. (2021) Susheel Suresh, Pan Li, Cong Hao, and Jennifer Neville. 2021. Adversarial graph augmentation to improve graph contrastive learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (2021), 15920–15933.

- Tang et al. (2015) Jian Tang, Meng Qu, Mingzhe Wang, Ming Zhang, Jun Yan, and Qiaozhu Mei. 2015. LINE: Large-scale information network embedding. In The Web Conference. 1067–1077.

- Togninalli et al. (2019) Matteo Togninalli, Elisabetta Ghisu, Felipe Llinares-López, Bastian Rieck, and Karsten Borgwardt. 2019. Wasserstein weisfeiler-lehman graph kernels. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (2019).

- Veličković et al. (2018) Petar Veličković, Guillem Cucurull, Arantxa Casanova, Adriana Romero, Pietro Lio, and Yoshua Bengio. 2018. Graph attention networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Velickovic et al. (2019) Petar Velickovic, William Fedus, William L Hamilton, Pietro Liò, Yoshua Bengio, and R Devon Hjelm. 2019. Deep Graph Infomax. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Wang et al. (2020) Ning Wang, Minnan Luo, Kaize Ding, Lingling Zhang, Jundong Li, and Qinghua Zheng. 2020. Graph few-shot learning with attribute matching. In ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management. 1545–1554.

- Wang et al. (2022) Song Wang, Yushun Dong, Xiao Huang, Chen Chen, and Jundong Li. 2022. FAITH: Few-Shot Graph Classification with Hierarchical Task Graphs. In International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

- Wen et al. (2021) Zhihao Wen, Yuan Fang, and Zemin Liu. 2021. Meta-inductive node classification across graphs. In International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. 1219–1228.

- Wu et al. (2020) Zonghan Wu, Shirui Pan, Fengwen Chen, Guodong Long, Chengqi Zhang, and S Yu Philip. 2020. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 32, 1 (2020), 4–24.

- Xia et al. (2022) Jun Xia, Yanqiao Zhu, Yuanqi Du, and Stan Z Li. 2022. A survey of pretraining on graphs: Taxonomy, methods, and applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.07893 (2022).

- Xu et al. (2019) Keyulu Xu, Weihua Hu, Jure Leskovec, and Stefanie Jegelka. 2019. How powerful are graph neural networks?. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Ying et al. (2018) Zhitao Ying, Jiaxuan You, Christopher Morris, Xiang Ren, Will Hamilton, and Jure Leskovec. 2018. Hierarchical graph representation learning with differentiable pooling. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 31 (2018), 4805–4815.

- You et al. (2021) Yuning You, Tianlong Chen, Yang Shen, and Zhangyang Wang. 2021. Graph contrastive learning automated. In International Conference on Machine Learning. 12121–12132.

- You et al. (2020) Yuning You, Tianlong Chen, Yongduo Sui, Ting Chen, Zhangyang Wang, and Yang Shen. 2020. Graph contrastive learning with augmentations. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020), 5812–5823.

- Zhang et al. (2021) Jiayou Zhang, Zhirui Wang, Shizhuo Zhang, Megh Manoj Bhalerao, Yucong Liu, Dawei Zhu, and Sheng Wang. 2021. GraphPrompt: Biomedical Entity Normalization Using Graph-based Prompt Templates. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.03002 (2021).

- Zhang and Chen (2018) Muhan Zhang and Yixin Chen. 2018. Link prediction based on graph neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 31 (2018).

- Zhang et al. (2018) Muhan Zhang, Zhicheng Cui, Marion Neumann, and Yixin Chen. 2018. An end-to-end deep learning architecture for graph classification. In AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, Vol. 32.

- Zhou et al. (2019) Fan Zhou, Chengtai Cao, Kunpeng Zhang, Goce Trajcevski, Ting Zhong, and Ji Geng. 2019. Meta-GNN: On few-shot node classification in graph meta-learning. In ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management. 2357–2360.

Appendices

A. Algorithm and Complexity Analysis

Algorithm. We present the algorithm for prompt design and tuning of GraphPrompt in Alg. 1. In line 1, we initialize the prompt vector and the objective . In lines 2-3, we obtain the node embeddings of input graphs based on the pre-trained GNN. In lines 5-13, we accumulate the loss for the given tuning samples. In particular, in lines 5-6, we design the prompt for the specific task . In lines 7-8, we calculate the subgraph representation for each class prototype. Then, in lines 9-13, we calculate and accumulate the loss and get the overall objective. Finally, in line 14 we optimize the prompt vector by minimizing the objective .

Complexity analysis. For a node , with average degree , GNN layers, hops for subgraph extraction, hidden dimensions, the complexity of GNN-based embedding calculation is , and the complexity of subgraph extraction is . Thus, the embedding calculation of ’s subgraph with ReadOut is , where are small constants. Furthermore, if some neighborhood sampling (Hamilton et al., 2017) is adopted during GNN aggregation, is a relatively small constant too.

B. Further Descriptions of Datasets

We provide further details of the datasets.

(1) Flickr (Wen et al., 2021) is an image sharing network, which is collected by SNAP222https://snap.stanford.edu/data/. In particular, each node is an image, and there exists an edge between two images if they share some common properties, such as commented by the same user, or from the same location. Each image belongs to one of the 7 categories.

(2) PROTEINS (Borgwardt et al., 2005) is a collection of protein graphs which include the amino acid sequence, conformation, structure, and features such as active sites of the proteins. The nodes represent the secondary structures, and each edge depicts the neighboring relation in the amino-acid sequence or in 3D space. The nodes belong to three categories, and the graphs belong to two classes.

(3) COX2 (Rossi and Ahmed, [n. d.]) is a dataset of molecular structures including 467 cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, in which each node is an atom, and each edge represents the chemical bond between atoms, such as single, double, triple or aromatic. All the molecules belong to two categories.

(4) ENZYMES (Wang et al., 2022) is a dataset of 600 enzymes collected from the BRENDA enzyme database. These enzymes are labeled into 6 categories according to their top-level EC enzyme.

(5) BZR (Rossi and Ahmed, [n. d.]) is a collection of 405 ligands for benzodiazepine receptor, in which each ligand is represented by a graph. All these ligands belong to 2 categories.

Note that we conduct node classification on Flickr, PROTEINS and ENZYMES, since their node labels generally appear on all the graphs, which is suitable for the setting of few-shot node classification on each graph. Note that, we only choose the graphs which consist of more than 50 nodes for the downstream node classification, to ensure there exist sufficient labeled nodes for testing. Additionally, graph classification is conducted on PROTEINS, COX2, ENXYMES and BZR. We use the given node features in the cited datasets to initialize input feature vectors, without additional processing.

C. Further Descriptions of Baselines

In this section, we present more details for the baselines, which are chosen from three main categories.

(1) End-to-end graph neural networks.

-

•

GCN (Kipf and Welling, 2017): GCN resorts to mean-pooling based neighborhood aggregation to receive messages from the neighboring nodes for node representation learning in an end-to-end manner.

-

•

GraphSage (Hamilton et al., 2017): GraphSAGE has a similar neighborhood aggregation mechanism with GCN, while it focuses more on the information from the node itself.

-

•

GAT (Veličković et al., 2018) : GAT also depends on neighborhood aggregation for node representation learning in an end-to-end manner, while it can assign different weights to neighbors to reweigh their contributions.

-

•

GIN (Xu et al., 2019): GIN employs a sum-based aggregator to replace the mean-pooling method in GCN, which is more powerful in expressing the graph structures.

(2) Graph pre-training models.

-

•

DGI (Velickovic et al., 2019): DGI capitalizes on a self-supervised method for pre-training, which is based on the concept of mutual information (MI). It maximizes the MI between the local augmented instances and the global representation.

-

•

InfoGraph (Sun et al., 2020b): InfoGraph learns a graph-level representation, which maximizes the MI between the graph-level representation and substructure representations at various scales.

-

•

GraphCL (You et al., 2020): GraphCL applies different graph augmentations to exploit the structural information on the graphs, and aims to maximize the agreement between different augmentations for graph pre-training.

(3) Graph prompt models.

-

•

GPPT (Sun et al., 2022). GPPT pre-trains a GNN model based on the link prediction task, and employs a learnable prompt to reformulate the downstream node classification task into the same format as link prediction.

D. Further Implementation Details

For baseline GCN (Kipf and Welling, 2017), we employ a 3-layer architecture, and set the hidden dimension as 32. For GraphSAGE (Hamilton et al., 2017), we utilize the mean aggregator, and employ a 3-layer architecture. The hidden dimension is also set to 32. For GAT (Veličković et al., 2018), we employ a 2-layer architecture and set the hidden dimension as 32. Besides, we apply 4 attention heads in the first GAT layer. Similarly, for GIN (Xu et al., 2019), we also employ a 3-layer architecture and set the hidden dimension as 32. For the pre-training and prompting approaches, we use the backbones in their original paper. Specifically, for DGI (Velickovic et al., 2019), we use a 1-layer GCN as the backbone, and set the hidden dimension as 512. Besides, we utilize PReLU as the activation function. For InfoGraph (Sun et al., 2020b), we use a 3-layer GIN as the backbone, and set its hidden dimension as 32. For GraphCL (You et al., 2020), we also employ a 3-layer GIN as its backbone, and set the hidden dimension as 32. In particular, we choose the augmentations of node dropping and subgraph, with a default augmentation ratio of 0.2. For GPPT (Sun et al., 2022), we utilize a 2-layer GraphSAGE as its backbone, set its hidden dimension as 128, and utilize the mean aggregator. For our proposed GraphPrompt, we employ a 3-layer GIN as the backbone, and set the hidden dimensions as 32. In addition, we set to construct 1-hop subgraphs for the nodes.

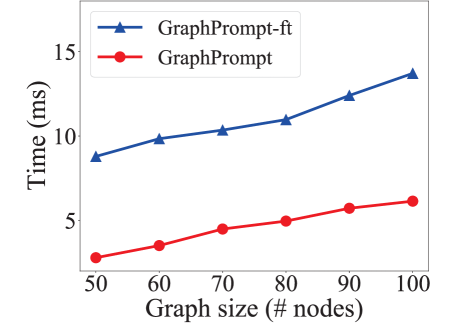

E. Further Experimental Results

Scalability study. We investigate the scalability of GraphPrompt on the dataset PROTEINS for graph classification. We divide the graphs into six groups based on their size (i.e., number of nodes). The size of graphs in each group is approximately 50, 60, , 100 nodes. We sample 10 graphs from each group, and record the prompt tuning time on the 10 graphs in each epoch. The results are presented in Fig. 6. Note that we also report the tuning time for GraphPrompt-ft, a variant of GraphPrompt, which fine-tunes all the parameters including the pre-trained GNN weights. We first observe that the tuning time of our GraphPrompt increases linearly as the graph size increases, demonstrating the scalability of GraphPrompt on larger graphs. In addition, compared to GraphPrompt, GraphPrompt-ft needs more tuning time, showing the inefficiency of the fine-tuning paradigm.

Parameter sensitivity. We evaluate the sensitivity of two important hyperparameters in GraphPrompt, and show the impact in Figs. 7 and 8 for node classification and graph classification, respectively.

For the number of hops () in subgraph construction, the performance on node classification gradually decreases as the number of hops increases. This is because a larger subgraph tends to bring in irrelevant information for the target node, and may suffer from the over-smoothing issue (Chen et al., 2020). On the other hand, for graph classification, the number of hops only affects the pre-training stage as the whole graph is used in downstream classification. In this case, the number of hops does not show a clear trend, implying less impact on graph classification since both small and large subgraphs are helpful in capturing substructure information at different scales.

For the hidden dimension, a smaller dimension is better for node classification, such as 32 and 64. For graph classification, a slightly larger dimension might be better, such as 64 and 128. Overall, 32 or 64 appears to be robust for both node and graph classification.

F. Data Ethics Statement

To evaluate the efficacy of this work, we conducted experiments which only use publicly available datasets, namely, Flickr333https://snap.stanford.edu/data/web-flickr.html, PROTEINS, COX2, ENZYMES and BZR444https://chrsmrrs.github.io/datasets/, in accordance to their usage terms and conditions if any. We further declare that no personally identifiable information was used, and no human or animal subject was involved in this research.