General solution for the vacuum electromagnetic field in the surroundings of a rotating star.

1 Abstract

Many recent observations of pulsars and magnetars can be interpreted in terms of neutron stars (NS) with multipole electromagnetic fields. As a first approximation, we investigate the multipole magnetic and electric fields in the environment of a rotating star when this environment is deprived of plasma. We compute a multipole expansion of the electromagnetic field in vacuum for a given magnetic field on the conducting surface of the rotating star. Then, we consider a few consequences of multipole fields of pulsars. We provide an explicit form of the solution. For each spherical harmonic of the magnetic field, the expansion contains a finite number of terms. A multipole magnetic field can provide an explanation for the stable sub-structures of pulses, and they offer a solution to the problem of current closure in pulsar magnetospheres. This computation generalises the widely used model of a rotating star in vacuum with a dipole field. It can be especially useful as a first approximation to the electromagnetic environment of a compact star, for instance a neutron star, with an arbitrarily magnetic field.

2 Introduction

Dipole magnetic fields have two important properties that contribute to their success in the modelling of a pulsar magnetosphere: dipole fields dominate higher order multipole fields at large distances from the neutron star, and they are computationally simpler. Mostly based on the consideration of spin-up lines in the diagram, Arons (1993) showed that low-altitude magnetic fields of pulsars are dominated by their dipole component, the non-dipole component not exceeding 40% of the dipole field. However, several observations tend to show that multipole magnetic fields cannot be neglected in every pulsar.

Gotthelf et al. (2013) measured period derivatives for the pulsar PSR J0821-4300 . It is a central compact object (CCO) in a supernova remnant. They found exceptionally weak dipole magnetic field components for a young neutron star, about G. Antipodal surface hot spots with different temperatures and areas were deduced from the X-ray spectrum and pulse profiles. Such non-uniform surface temperature appears to require strong crustal magnetic fields, probably toroidal or quadrupolar components much stronger than the external dipole.

The pulsar J2144-3933, with a period of 8.51 s, is beyond the death-line in the diagram and according to standard emission models. The pulsar should not emit radio-waves. Death-line models strongly depend on magnetic field lines curvatures. For a given surface magnetic dipole field strength, pulsars with strong multipolar field components have a highly curved field near the stellar surface that might permit the radio emission of the pulsar J2144-3933 (Young et al. 1999). Indeed, Harding & Muslimov (2011) has shown that a simply offset dipole field can increase the pair-cascade efficiency, and lower the death-line in the diagram.

Multi-wavelength observations of intermittent radio emissions from rotation-powered pulsars beyond the pair-cascade death line, of the pulse profile of the magnetar SGR 1900+14 after its 1998 August 27 giant flare and of the X-ray spectral features of PSR J0821-4300 and SGR 0418+5729, suggest that the magnetic fields of non-accreting neutron stars are not purely dipolar and may contain higher order multipoles (Mastrano et al. 2013).

Güver et al. (2011) analysed upper bound on the spin-down rate and the high signal-to-noise ratio XMM-Newton spectra of the soft gamma-ray repeater SGR 0418+5729. They found a low surface magnetic field in comparison to other magnetars: G. In connection to the spin-down limits, this implies a significantly multipole structure of the magnetic field.

Most attempts to model the pulses profiles of pulsars are based on dipole magnetic fields. But some features of these profiles resist the models. Let us consider, for instance, the brightest pulsar A of the two pulsars binary system PSR J0737-3039. The radio pulse profiles of PSR J0737-3039A consist of two peaks shown in Fig. 1 (Kramer & Stairs 2008). Geometrical models have been produced with best-fit one and two pole models (Ferdman et al. 2013), two Poles Caustics (TPC), Outer Gap (OG) (Guillemot et al. 2013) and a retarded vacuum dipole polar cap (Perera et al. 2014). With these models, one can reconstruct the main angles defining the orbital plane, rotation axis and magnetic inclination of the pulsar, as well as the general shape of the pulses. For instance Ferdman et al. (2013) could reconstruct a Gaussian fit, and Perera et al. (2014) considered pulse width at four intensity levels. All these models involve a dipole magnetic field. They found that the two peaks are more likely to be associated with the two poles. But the peaks (especially the less intense one) show sub-structures that do not enter into their models. The sub-structures (a spiky plateau above the 75% intensity level before the main maximum, and a plateau at the 10 % level after the main maximum) occupy a significant proportion of the total phase angle. It is quite possible that these sub-structures are associated with multipole components of the electromagnetic environment of the neutron star.

Another example can be seen in the gamma rays profile of the Vela pulsar revealed by the Fermi-LAT telescope (Abdo et al. 2009) displayed in Fig. 2. Again, this profile contains large sub-structures. It also exhibits shorter sub-structures, which are visible in the enlarged insets. Here again, multipole components might be a cause of pulses sub-structures.

As recalled by Perera et al. (2014), in general, pulsar magnetosphere models are constructed at the following two limits: (a) a vacuum limit (Deutsch 1955), and (b) a force-free magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) limit with a plasma-filled magnetosphere (Spitkovsky 2006). However, a true magnetosphere operates between these two limits. We could expect that the MHD solutions are more realistic, but Harding & Muslimov (2011) found that the rotating dipole magnetosphere in vacuum, in many cases, provides better fits to observed gamma rays pulse profiles than the force-free magnetosphere. This is for instance what they found for Vela. This shows that the vacuum magnetosphere is still a useful approximation in pulsar physics.

Considering this general remark and the possible relevance of multipole electromagnetic fields to pulsar models, we present an analytically exact model of the vacuum magnetosphere where the neutron star magnetic field is expanded in multipole components.

Suitable boundary conditions are taken into account for an oblique rotator with a conducting surface. This algorithm allows us to describe electromagnetic fields with quantum numbers as high as (). This algorithm is a generalisation of the one described by Deutsch (1955) for a simple magnetic dipole ().

In section 3, we present the method of resolution of the Maxwell equations and their boundary conditions. In the section 4, we present the parallel solutions () for any value of . Section 5 contains the general solution of the Maxwell equation with the required boundary conditions for given quantum numbers . The numbers correspond to the perpendicular case, i.e. where the axis of the mutipole is orthogonal to the axis of the neutron star. Thanks to the linearity of the Maxwell equation, the general solution is a linear combination of the perpendicular and parallel solutions. The matching conditions are applied in section 6. Details of the analytical calculations are presented in appendices A-B.

After this derivation, two applications of multipoles are suggested. The first concerns the problem of the pulsar current closure, and the second concerns the pulse profile of pulsars such as PSR J0737-3039A and Vela.

3 Methods

Vectors are expanded in spherical coordinates of axis parallel to the angular velocity vector of the neutron star.

Following Bonazzola et al. (2007) let us define the components of the magnetic field as the usual radial component , and two scalar fields, and , such that

| (1) |

The magnetic fields, and and , are also related through the relations

| (2) | |||||

The magnetic field associated with , noted is transverse/toroidal (i.e. ) as well as the electric derived from , noted (i.e. ), defining the poloidal electromagnetic field. The magnetic and electric field , around a magnetised spinning star , can be considered the sum of the poloidal field (, ) and a toroidal field (, ),

| (3) |

The vector and must be solutions of the Maxwell equations in the vacuum

| (4) |

The Maxwell equations (4) expressed in term of and of the coefficients and become

| (5) | |||||

| (6) | |||||

| (7) |

where

| (8) | |||||

is the angular Laplacian. When it is time dependent, the electric field is deduced from and through the Faraday equation and the relations

| (9) | |||||

After separation of the variables, it is found that the angular solution of Eqs. 5-6 can be expanded in spherical harmonic functions , where are the associated Legendre functions. The scalars , , , are the spherical coordinates the axis being the star spin axis.

Two cases must be treated separately, depending on . When , the solution is axially symmetric, and not time dependent. The parts depending on in Eqs. (5-7) are simple differential equations with elementary solutions. When , the solution is time dependent, and the parts of Eqs. 5-7 that depend on can be converted into Bessel equations of the normalised variable .

We solve the and solutions separately. The solution is derived from and has a finite radial magnetic component given by Eq. (5). This equation is solved directly (see the following sections). Then, using the divergence of the magnetic field

| (10) |

and the fact that with a angular dependence , we find . Then, from Eq. (3),

| (11) |

The magnetic field is derived from . The field is found directly by resolution of Eq. (6).

The computation of the electric field is different in the cases and , which is detailed in sections 4 and 5. The outgoing solution of the Maxwell Eqs.(4) must also satisfy the boundary conditions (BC)

| (12) |

at the surface of the star, where is the unit vector orthogonal to the surface of the star, and is the radial vector connecting the centre of the star to the point of interest on its surface.

Let be the radius of the spherical neutron star (NS). Inside of the NS , the magnetic field is generated by internal currents. Let be the component of the spectral decomposition of . The electric field inside the NS is

| (13) |

The matching conditions are (See Eq.(12))

| (14) |

and

| (15) |

where is the field in the vacuum.

4 Axially symmetric solutions and their matching conditions

In this section, we compute the multipole electromagnetic field around a rotating neutron star satisfying axially symmetric BC In terms of spherical harmonics, they correspond to . When , there is a finite solution derived from Eq. (6), but the curl of this magnetic field is finite too. This means that there is either a time varying electric field, or an electric current density. Because , a time varying electric field is discarded. Since we are looking for a vacuum solution, a current density is discarded too. Therefore, only a electromagnetic field is retained in the axially symmetric case .

Following the method exposed in section 3, it is found that the components of the vacuum magnetic field are:

| (16) |

where and is the Legendre polynomial of order . If the interior of the rotating star is a perfect conductor, the internal electric field vanishes in the co-rotating frame. Consequently, the electric field in the inertial frame is and

| (17) |

The value of , and at the surface of the star determine the boundary condition for the external field. Outside the star ( ), the electric field must be the gradient of an harmonic potential (No charge in the vacuum, steady magnetic field)

| (18) |

and its component must match the components inside the star:

| (19) |

This imposes a series of constraints on the coefficients . The relation

| (20) |

is deduced from the derivative of Eq. 8.914.2 in Gradshteyn et al. (2007) and the differential equation defining the Legendre functions (Eq. 8.820, same reference). Equation (20) is used to deduce the values of the coefficients from Eq. (19). Finally,

| (21) |

We have added in and the effect of a possible global electric charge of the NS.

5 The non-axially symmetric solutions

The solutions corresponding to magnetic fields with an inclination over the axis correspond to . They are developed in this section.

The solution includes a magnetic field with a finite radial component . The solution of Eq. (5) is

| (22) |

where , is the light velocity,* , and is the associated Legendre polynomial of order . The function is the spherical Hankel function

| (23) |

where is the Bessel function of semi-integer order and

| (24) |

and are constant numbers. Because the solutions involving are associated with an incoming wave, we do not keep them, and for simplicity, we use the notation for .

6 Matching conditions for the non-axially symmetric solutions

Let be the component of the internal field at the surface of the star. Taking into account the elementary expression of the external magnetic field given by Eq.(26) , the matching conditions described by Eq.(14) determine the coefficient in Eq.(26). We have

| (30) |

where . Note that the above B.C. is not sufficient to determine the magnetic field uniquely: in fact, an arbitrary toroidal component defined by can be added to the poloidal component in a such a way that the electric counterpart allows us to satisfy the boundary conditions

This equation reads

| (31) | |||

The details of its resolution are given in Appendix A. Only two coefficients remain in the right-hand side of Eq. (31); they are

| (32) |

and

| (33) |

where the coefficient is defined in Eq. (44). Finally, the and component of the total electric field are:

The electric field computed above, satisfies the boundary condition =0. It is shown in section B that they also fit the boundary condition given by Eq.(14)

For , we obtain the result given in Deutsch (1955).

7 A pulsar that extracts electrons from one pole and protons from the other

With dipole pulsar magnetosphere, the open field lines above the two opposite poles present vertical electric fields and Goldreich-Julian currents of the same sign. Therefore, the particles that are extracted from the two poles of the neutron star have the same electric charge. With pulsar dipole magnetosphere model ending with a wind, there is a continuous flux of emitted particles, and it is necessary to close the currents, otherwise the neutron star would accumulate electric charges. Charge accumulation cannot be indefinite, and it is generally assumed that the wind particles (of both positive and negative charges) come from pair creations. The pairs need a continuous flux of primary particles, however, and the question of charge neutrality, i.e. current closure, remains with the primary particles.

Static pulsar electrospheres (Pétri et al. 2002b) are models that do not involve charge circulation. Unfortunately, they do not create a wind either, and they are not expected to radiate. Aligned electrospheres have a dome of charged particles of one sign above each pole, and an equatorial belt of particles of the opposite sign. In that configuration, a dicotron instability can develop. The dicotron effect tends to modulate the shape of the equatorial belt, and it can expel some of its particles (Pétri et al. 2002a). Then, particles of the two signs can be ejected from the neutron star, and this solves the problem of charge neutrality and current closure.

In the present section, we present an alternative to electrospheres and dicotron instability that solves the charge neutrality problem. It consists of a neutron star with a multipole magnetic field. For simplicity, we consider only an aligned dipole and a quadrupole component.

We have

| (36) |

| (37) |

where characterises the quadrupole component amplitude.

The radial electric field is

where and is an integration constant depending on the total charge of the star.

In what follows, we consider a dynamical process: the electrons are extracted and accelerated from the north pole () and at time , .

Electrons are accelerated above the star surface and they create electron-positron pairs. The vacuum electric field is then progressively screened by the pairs. If the protons remain attached in the vicinity of the star, the magnetosphere charges as long as the electrons are extracted and accelerated. Then, the total electric charge of the star increases. Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of the radial electric field at the two poles. It is shown that if increases (beware of signs, the normalised charge decreases) the radial electric fields on the north pole is less negative, and those on the south pole becomes more positive. Provided that , a finite range of values of (highlighted by a grey rectangle) allows for radial electric fields of opposite signs at the opposite poles.

Fig. 4 shows a numerical example of superimposed and aligned dipole and quadrupole fields. The only finite multipole components are characterised by the coefficients (here purely real) -1, and -2.5 and the total electric charge is C. The electromagnetic field is computed on a spherical grid extending from the star surface to a distance of 716.2 star radii (15 light cylinder radii). The figure only represents the area very close to the star, where the quadrupole component is noticeable. The magnetic field has the intensity T on the surface, and the dipole angle with the rotation axis is null. The period of rotation of the star is 10 ms, which corresponds to a rotation frequency 628 s-1 and to a light cylinder radius m. We can see (colour code) the radial electric field on the left-hand side as well as magnetic field lines. Because of the quadrupole component, the radial electric field does not have the same value on the two poles. Its high negative value on the north pole is appropriate for the acceleration of electrons out of the star. On the north pole, the positive electric field can accelerate positive ions.

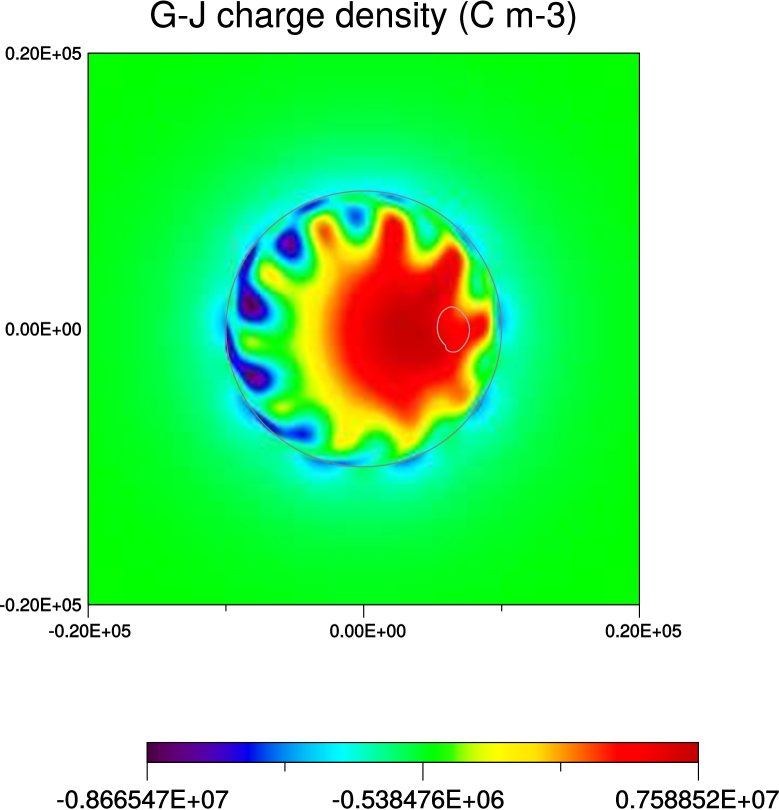

In comparison to (not shown on a figure), the radial electric field amplitude with is reduced (but still negative) in the north pole and more positive in the south pole, where protons can be accelerated. Then, the ability of the proton to create pairs is increased, while those of the electron to create pairs remain high. When pairs are created above the two opposite poles, a stationary regime is attained where both electrons and protons are extracted from the star, the total charge reaches an asymptotic value , and the pulsar can be active. Of course, in this regime, and especially if the NS surface is hot, the Goldreich-Julian density is an important marker of primary charge extraction. We can see on Fig. 5 that the Goldreich-Julian density also has opposite signs at opposite poles ( is the rotational velocity).

Of course, above the pair creation fronts, the electromagnetic field cannot correspond to the vacuum model derived in this paper. But this model is useful below the pair creation front, where the flux of primary particles is not expected to induce currents that could significantly change the magnetic field topology.

With this example, we do not argue that multipole fields are the most common solution to the pulsar current closure problem, but they represent at least one possibility.

At the opposite limit to vacuum approximation, the force-free equations of a magnetosphere were solved in a way that resolves the current system closure. This was done in 2D for an axially symmetric pulsar magnetosphere (Contopoulos et al. 1999; Gruzinov 2005, 2007) and for a 3D dissipative force-free magnetosphere where the magnetic axis is not necessarily aligned with the rotation axis (Spitkovsky 2006; Kalapotharakos & Contopoulos 2009). Those models are based on a dipole magnetic field at the NS surface. The current closes through an equatorial current sheet where the current is opposite to that carried in the open field lines regions. Since force-free equations do not include the plasma transport equations (no explicit equation of density and momentum, for instance), the force-free models do not say much about the nature of the particles that carry currents. It is generally argued that the equatorial return current is carried by electrons that were launched in open field line regions, as well as by positrons moving to the opposite direction, which result from pair creation cascades initiated by primary accelerated electrons.

At a large distance from the NS, a vacuum solution associated with a multipolar electromagnetic field is not different from that associated with a dipole field. This probably holds with a plasma filled magnetosphere. Force-free magnetosphere associated with a surface multipole field might be very analogous to those with dipole fields at distances larger than a fraction of the light-cylinder radius, but the current sheet could be different near the star. As we will see in the next section, this can affect the pulse shape.

8 Pulse shape

In the standard model of the magnetosphere, the strong electric field at the surface of the star extract and accelerate electrons from the crust at relativistic energy. The current density is where is the Goldreich-Julian density. Those primary electrons follow the lines of the magnetic field radiate high-energy rays via curvature radiation, and the gamma rays produce electron positron pair via the magnetic field , if is strong enough, or by rays and crust thermal background -ray mechanism. Electron positron pairs are supposed to generate the observed radio high energy emission. The main consequence of this mechanism is that the observed pulse shapes depends strongly on the Goldreich-Julian density at the surface of the star.

As mentioned in the introduction, the most often invoked heuristic models to explain pulse shapes are the polar cap model, the slot gap and caustics models, and the outer gap model. In most of these models, a critical area where determines the pulse shape is the curve drawn on the NS surface that corresponds to the feet of the last open field lines. Figure 6 shows at the NS surface at the feet of the last open magnetic field lines for a dipole field with an inclination deg. Its variations are very simple, symmetric, with a single maximum and a single minimum. Multipole components are now added to this dipole field. Their coefficients are displayed in Table 1. The Goldreich-Julian density on the NS surface is displayed in Fig. 7. We can see the inclined dipole structure and the superimposition of smaller scale structures with a significant azimuthal modulation. The line corresponding to the feet of the last open field lines is displayed (for the northern hemisphere). The values of are displayed in Fig. 8 as a function of the abscissa along the line. We can see that it is more complex than the dipole profile in Fig. 6. The curve has secondary extrema and it shows a higher range of values. Without entering into the detail of pulse shape theories (it is not the topics of the present paper), we can expect that the multipole field can be associated with irregular pulse shapes like those displayed in Figs. 1 and 2.

| 1 | 0 | 0.766E+00 0.000E+00, |

| 1 | 1 | 0.643E+00 0.000E+00, |

| 11 | 9 | 0.255E-24 -0.126E-23, |

| 11 | 10 | 0.456E-24 -0.120E-23, |

| 12 | 7 | 0.594E-27 -0.246E-27, |

| 12 | 8 | 0.128E-26 -0.630E-26, |

| 12 | 9 | 0.128E-26 -0.630E-26, |

| 12 | 10 | 0.600E-26 -0.230E-26, |

9 Conclusion

We have developed an analytical formalism allowing us the most general solution for an electromagnetic field in vacuum fulfilling the boundary conditions on the surface of a rotating magnetised star. This solution, based on an expansion on spherical harmonics is the linear combination of two types of contributions : axially symmetric fields (azimuthal number ) given by Eqs. Eq. (16, 21), and non-axially symmetric fields () given by Eq. (6, 6).

Of course, NS are well known to extract plasma in their immediate vicinity, therefore this solution cannot be used as is. Nevertheless, we showed in section 7 that the presence of a quadrupole component of the magnetic field can solve the problem of the current closure in the pulsar magnetosphere. As suggested in section 8, this formalism can also be useful in modelling the observed pulse shapes in pulsars emission.

This solution can be used as a benchmark for codes solving the electromagnetic field equations in the surrounding of a rotating magnetised star.

Pétri (2013) has built numerical solutions of the electromagnetic field surrounding a star with a dipole field in the context of general relativity. Our model does not include gravitational effects, but it is possible that a numerical solution can be developed as well. The present solution can be used as a test when strong gravitational effects are neglected.

Moreover, the vacuum electromagnetic solution can be the first step in an iterative process to find more suitable pulsar models, where a plasma is (numerically) progressively introduced into the NS environment.

Appendix A Derivation of the coefficients

The coefficients are computed by taking the proprieties of the associated Legendre functions into account. We obtain: (Eq. 8.733,1 in Gradshteyn et al. 2007)

| (39) |

or equivalently

| (40) |

By using the expression (Eq.(8.731,2) in Gradshteyn et al. (2007))

| (41) |

and Eq.(40) reads

| (42) |

By replacing the above value of in Eq.(31) we obtain

| (43) |

where

| (44) |

By multiplying both sides of Eq.(43) by , after the integration on between and , and on between and , with Eq.(42) and the orthogonality properties of the associated Legendre functions ,

| (45) |

only two coefficients survive,we obtain Eq. (32). Equation 33 is derived in an analogous way.

Appendix B Proof that the last boundary condition is fulfilled

We obtained a solution that fulfils the condition . Does it fit the last condition imposed by the boundary condition ? From Eqs. 26-5, this requirement is equivalent to

| (46) |

When the coefficients and are expressed using Eqs. 32 and 33, the requirement becomes

Considering the derivative of Eq. (42) relatively to , the condition becomes

| (47) |

By definition, the Lagrange polynomials are the solutions of the differential equation

| (48) |

With , this differential equation results in the nullity of the expression in Eq. (47). This proves that the boundary condition is fulfilled, and that the electromagnetic field derived in section 6 is a consistent solution of the problem.

References

- Abdo et al. (2009) Abdo, A. A., Ackermann, M., Atwood, W. B., et al. 2009, ApJ, 696, 1084

- Arons (1993) Arons, J. 1993, ApJ, 408, 160

- Bonazzola et al. (2007) Bonazzola, S., Villain, L., & Bejger, M. 2007, Classical and Quantum Gravity, 24, 221

- Contopoulos et al. (1999) Contopoulos, I., Kazanas, D., & Fendt, C. 1999, Astrophysical Journal, 511, 351

- Deutsch (1955) Deutsch, A. J. 1955, Annales d’Astrophysique, 18, 1

- Ferdman et al. (2013) Ferdman, R. D., Stairs, I. H., Kramer, M., et al. 2013, ApJ, 767, 85

- Gotthelf et al. (2013) Gotthelf, E. V., Halpern, J. P., & Alford, J. 2013, Astrophysical Journal, 765, 58

- Gradshteyn et al. (2007) Gradshteyn, I. S., Ryzhik, I. M., Jeffrey, A., & Zwillinger, D. 2007, Table of Integrals, Series, and Products (Academic Press)

- Gruzinov (2005) Gruzinov, A. 2005, Physical Review Letters, 94, 021101

- Gruzinov (2007) Gruzinov, A. 2007, ApJL, 667, L69

- Guillemot et al. (2013) Guillemot, L., Kramer, M., Johnson, T. J., et al. 2013, Astrophysical Journal, 768, 169

- Güver et al. (2011) Güver, T., Göǧüş, E., & Özel, F. 2011, MNRAS, 418, 2773

- Harding & Muslimov (2011) Harding, A. K. & Muslimov, A. G. 2011, Astrophysical Journal Letters, 726, L10

- Kalapotharakos & Contopoulos (2009) Kalapotharakos, C. & Contopoulos, I. 2009, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 496, 495

- Kramer & Stairs (2008) Kramer, M. & Stairs, I. H. 2008, ARAA, 46, 541

- Mastrano et al. (2013) Mastrano, A., Lasky, P. D., & Melatos, A. 2013, MNRAS, 434, 1658

- Perera et al. (2014) Perera, B. B. P., Kim, C., McLaughlin, M. A., et al. 2014, ApJ, 787, 51

- Pétri (2013) Pétri, J. 2013, MNRAS, 433, 986

- Pétri et al. (2002a) Pétri, J., Heyvaerts, J., & Bonazzola, S. 2002a, A&A, 387, 520

- Pétri et al. (2002b) Pétri, J., Heyvaerts, J., & Bonazzola, S. 2002b, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 384, 414

- Spitkovsky (2006) Spitkovsky, A. 2006, ApJL, 648, L51

- Young et al. (1999) Young, M. D., Manchester, R. N., & Johnston, S. 1999, Nature, 400, 848