Gender Bias Hidden Behind Chinese Word Embeddings:

The Case of Chinese Adjectives

Abstract

Gender bias in word embeddings gradually becomes a vivid research field in recent years. Most studies in this field aim at measurement and debiasing methods with English as the target language. This paper investigates gender bias in static word embeddings from a unique perspective, Chinese adjectives. By training word representations with different models, the gender bias behind the vectors of adjectives is assessed. Through a comparison between the produced results and a human scored data set, we demonstrate how gender bias encoded in word embeddings differentiates from people’s attitudes.

BIAS STATEMENTThis paper studies gender bias in Chinese adjectives, captured by word embeddings. For each Chinese adjective, a gender bias score is calculated by (Bolukbasi et al., 2016). A positive score represents the Chinese adjective word embeddings is more associated with males, and a negative value refers to the opposite result. In our daily life, we find that gender stereotypes can be conveyed by adjectives. The close association between an adjective and a certain gender could be the accomplice in forming gender stereotypes (Menegatti and Rubini, 2017). If these stereotypes are learned by the adjective word embeddings, they would be propagated to downstream NLP applications; accordingly, the gender stereotypes would be reinforced in users’ mind. For example, the system will tend to use “smart” to describe males because of the existed social stereotype in training data that males are good at mathematics; then, the influence of the stereotype would be spread and increased again. Thus, we want to further investigate the bias encoded by the embeddings and how they are different with what in people’s mind.

1 Introduction

In the deep learning era, a major area of NLP has concerned the representation of words in low-dimensional and continuous vector spaces. People propose different algorithms to achieve such goal, including Word2Vec (Mikolov et al., 2013a), GloVe (Pennington et al., 2014a) and FastText (Bojanowski et al., 2017). Word embeddings play an important role in many NLP tasks, such as machine translation (Qi et al., 2018) and sentiment analysis (Yu et al., 2017). However, several studies point out that word embeddings could capture the gender stereotypes in training data and transmit them to downstream applications (Bolukbasi et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017). The consequence is often unbearable. Take machine translation as an example, if we translate a sentence concerning “nurse” from a language with gender-neutral pronouns to English, a female pronoun might be automatically produced to denote “nurse” (Prates et al., 2019). Undoubtedly, this falls into the trap of the typical gender stereotypes. Therefore, the investigation of gender bias in word embeddings is necessary and accordingly attracts scholars’ attention in recent years (Bolukbasi et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017).

Most previous studies concerning gender bias in word embeddings only take English as the target language. Other languages are only included in several multi-lingual projects. For example, Prates et al. (2019) evaluate the gender bias in machine translation by translating 12 gender neutral languages with the Google Translate API; Lewis and Lupyan (2020) examine whether gender stereotypes could be reflected in the large-scale distributional structure of 25 natural languages. Apart from English, other languages have rarely been the target language in the research under this topic. This paper will take Chinese as the target language, investigating gender bias in word embeddings trained with the model designed for special features of Chinese.

The fact that social stereotypes are conveyed in our language is often neglected by the public. From the commonly used adjectives, we could get a glimpse of the social stereotypes of a certain group of people. These stereotypes would confine us to what we should be in the minds of the public. It has been confirmed that when describing different genders, people will choose divergent groups of adjectives even though such a choice might change with the development of society (Garg et al., 2018). Therefore, this study focuses on the problem of gender stereotypes from the perspective of adjectives. By scoring the gender bias from our trained vectors, we yield a subjective result of the gender preference of a set of adjectives. Through comparing our results with a handcrafted data set of human attitudes towards adjectives(Zhu and Liu, 2020), we find that what is encoded in word embeddings is, to some extent, inconsistent with people’s feelings on the gender preference of these adjectives.

2 Related work

Gender could affect the usage of adjectives (Lakoff, 1973). On the other hand, the attitude of the public towards the social roles of men and women could also be indicated by how adjectives correlates with genders(Zhu and Liu, 2020). In the past decade, an increasing number of studies investigating adjectives and gender stereotypes from various perspectives are proposed and developed. Baker (2013) reveals the stereotype in the description of boys and girls by analyzing adjectives only used for a certain gender with the aid of corpora covering a range of written genres. Research of Bollywood movies (Madaan et al., 2018) finds that different adjectives are chosen when they try to create impressive male and female roles. The significant divergence between the usage of adjectives for describing men and women has also been confirmed by Hoyle et al. (2019), and they also notice the variance is consistent with common stereotypes. Zhu and Liu (2020) trace the change of gender bias in Chinese adjectives based on a handcrafted data set that consists of the gender preference score of adjectives. However, the number of studies focusing on Chinese adjectives and gender bias is still limited.

Gender bias in word embeddings and the corresponding debiasing methods have been a vivid research field in recent years. Bolukbasi et al. (2016) and Caliskan et al. (2017) confirm that word embedding models could precisely capture the social stereotypes concerning people’s careers, such as the relationship in an analogy that Man is to Computer Programmer as Woman is to Homemaker. This bias could even be amplified by embedding models (Zhao et al., 2017). Besides English, other target languages like Swedish (Sahlgren and Olsson, 2019) and Dutch (Wevers, 2019) gradually attract the attention of researchers. Various methods for assessing bias and debiasing are proposed and developed in previous studies. Bolukbasi et al. (2016) firstly measure the gender bias by computing the projection of a word on direction, which has been confirmed strongly correlated with the public judgment of gender stereotypes. Based on this method, they also develop a debiasing method by post-processing the generated word vectors. Zhao et al. (2018) and Zhang et al. (2018) further propose to debias word embeddings in training procedure by changing the loss of GloVe model (Pennington et al., 2014b) and employing an adversarial network, respectively. Despite a large amount of research having been done in this field, to the best of our knowledge, no one has assessed the underlying gender bias behind adjectives, especially those in non-English languages.

To complement the full picture of gender bias encoded in word representation, this paper examines the problem from the perspective of adjectives rather than nouns of occupations that repeatedly appeared in previous studies. Based on the human scoring data set of Zhu and Liu (2020), we investigate the similarities and differences between the automatically captured gender bias in Chinese and people’s judgement.

3 Methodology

To uncover the gender stereotypes conveyed by adjectives, we first preprocess a corpus of online Chinese news and train word embeddings on it with two different models. Then, we calculate the gender bias scores based on the generated two vectors and compare them with the human scoring data set, Adjectives list with Gendered Skewness and Sentiment (AGSS) (Zhu and Liu, 2020).

3.1 Data

News reports are not only the reflection of social consciousness but also the easily collected corpus for many NLP tasks. Therefore, we choose a corpus of Chinese news reports as our training data set. It was collected and released by Sogou Labs, covering 18 themes of news from various Chinese news websites.111http://www.sogou.com/labs/resource/ca.php The details of the corpus are illustrated in Table 1. All texts in the data set are cleaned and preprocessed through the following steps.

-

1.

Extract the news content and change the encoding from gbk to utf-8. All the other information and metadata are removed.

-

2.

Remove the html tag by the regular expression and conduct Chinese word segmentation with jieba,222https://github.com/fxsjy/jieba a widely used Python module.

| Original size | 1.54GB |

| Size after preprocessing | 2.1GB |

| The number of tokens | 375.3M |

| The number of unique words | 100.7k |

3.2 Training and evaluation of word embeddings

The meaning of Chinese words is usually related to the semantic information carried by the characters (Hanzi) that they are comprised of. Figure 1 shows an example: the word “xianjing” means “demure”, which consists of two characters. The first one, “xian”, means refined but usually used for describing a woman; the second character “jing” means silent and quiet. The word inherits and combines the meaning of each character, even the information concerning gender. This feature of Chinese leads to the development of word embedding models in which word vectors are trained with the character-level information. However, no study before has provided any ideas about how the encoding of gender bias information will be affected by training embedding with character-level information. Therefore, we decide to train our vectors with one of such models, namely the character-enhanced word embedding model (CWE) (Chen et al., 2015). In addition to the word vector, this model also trains a vector for Chinese characters.

CWE is developed based on the framework CBOW (Mikolov et al., 2013b). CBOW aims at predicting the target word by understanding the surrounding context words. Practically, its objective is to maximize the average log probability given a word sequence . CWE modifies the way of representing the context words in the algorithm of CBOW, predicting target words by combining character embedding and word embedding. A context word in CWE would be represented as follows,

| (1) |

refers to the word embedding of ; represents the number of characters in ; is the representation of the -th character in . For comparison, we also train vectors on CBOW to show in the influence of character-level information. The Python library Gensim 333https://github.com/RaRe-Technologies/gensim is used for training the representation with CBOW, and the other with CWE is completed by the released code of Chen et al. (2015).444https://github.com/Leonard-Xu/CWE/tree/master/src To make the results comparable, we keep the same hyper-parameters for the two models. Detailed information is recorded in Table 2.

| Window size | 5 |

| Iteration | 5 |

| Dimension | 300 |

| Min_count | 8 |

| Num_threads | 12 |

To ensure the effective of the produced embeddings, we evaluate them by word analogy tasks and the corresponding tools developed by Li et al. (2018). The test data set of the task includes 17813 questions about morphological or semantic relations. 555https://github.com/Embedding/Chinese-Word-Vectors/tree/master/testsets The results are illustrated in table 3. Although the semantic task results are lower than the values given in the paper of Li et al. (2018), we still assume that they are reliable as the size of our training data is only the half of theirs.

| Model | Morphological | Semantic |

|---|---|---|

| Li et al. (2018) | 11.5 | 30.2 |

| CBOW | 11.1 | 23.5 |

| CWE | 19.7 | 24.6 |

3.3 Gender bias measurement and data set

We employ the method of Bolukbasi et al. (2016) to assess gender bias encoded in the trained embeddings. For each adjective, a gender bias score is calculated by based on its vector.666We use the Chinese translation of he and she when conducting experiments. A positive result presents that the word has a closer association with males, while a negative score implies that the word is more associated with females. The higher the absolute value, the more biased the adjective is. 0 means totally neutral.

Adjectives List with Gendered Skewness and Sentiment (AGSS) is a handcrafted data set built by questionnaire in the project of Zhu and Liu (2020). 6 linguists firstly select 466 Chinese adjectives that could describe people, then 116 gender-balanced respondents score these adjectives by questionnaires. The the scale of score 1 to 5 is used to reflect people’s attitude, with 1 being more related to female and 5 more related to male. Table 4 shows some example data from AGSS. Finally, 304 adjectives are scored larger than 3, 153 adjectives get score less than 3, and 9 are believed totally neutral. According to the statistics of AGSS, the adjectives chosen for this data set are more associated with males, so Zhu and Liu (2020) state that AGSS is with gender skewness. To analyze the results, we compare our gender bias scores from word embeddings with the AGSS scores. As they are on different scales, Pearson correlation coefficient is employed here. It could measure the the strength of the linear association between two variables, which returns a value between -1 and 1. indicates strong positive linear correlation, 0 indicates no linear correlation and indicates a strong negative linear correlation.

| Words | Gender skewness in AGSS |

|---|---|

| powerful | 4.44 |

| vuglar | 3.62 |

| selfless | 3.00 |

| cute | 2.26 |

| decorous | 1.59 |

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Gender bias scores from word embeddings

We calculate the gender bias score for the same adjectives with AGSS and conclude the basic statistics in Table 5. More adjectives are categorized into the group close to male. This is identified with what Zhu and Liu (2020) state about AGSS (mentioned in Section 3.3). However, it should be noticed that the average scores of both models result in a negative value. This might suggest that most absolute values of negative gender bias scores are much higher than the positive group.

| CBOW | CWE | |

|---|---|---|

| # pos. score | 283 | 316 |

| # neg. score | 183 | 150 |

| Avg. score | -0.02029 | -0.02945 |

4.2 Correlation between word vectors and AGSS

The Pearson correlation coefficients presented in Table 6 suggest the two categories of data are positively associated. However, the correlation is not that strong with only around 0.5, since the range of Pearson coefficient is from -1 to 1. Besides, the gender bias scores from the word embeddings trained with CWE are more associated with the human scores. This might suggest that the character-level information could help the model capture gender bias more precisely, or we should say such information could contribute to encoding what is in people’s minds.

| CBOW | CWE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0.489 | 0.503 | ||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 |

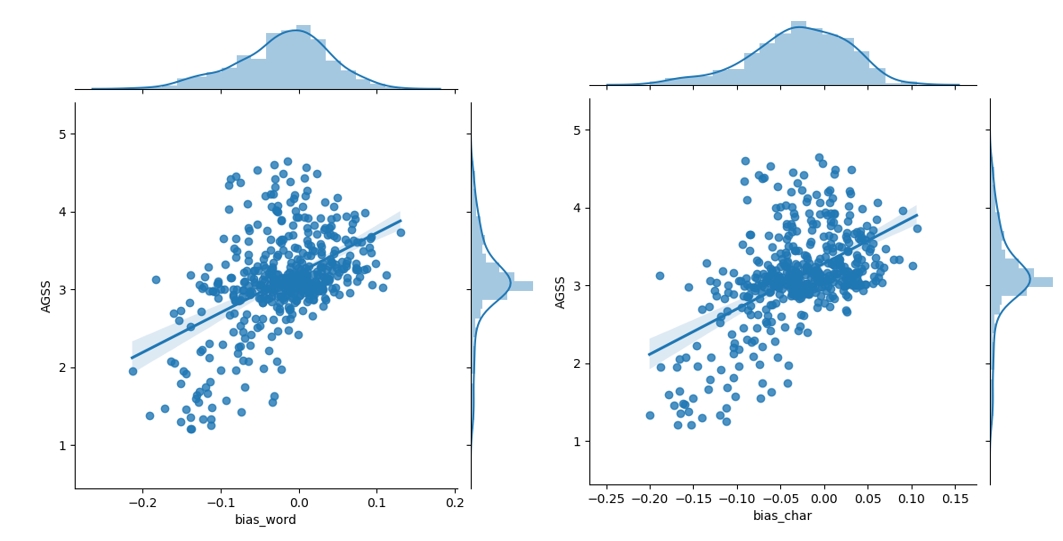

In Figure 2, we can find more details of the correlation between the two categories of data. By comparing the distribution of the two types of scores, we notice that the scores given by people are very concentrated between 2.5 to 3.5, while automatically calculated scores have a wider distribution. This might be caused by different scales, but may also come from people hypocrisy: they spontaneously narrow the extent of gender preference of words when they are asked to score their attitudes. Besides, it is a clear tendency that some words only for males in people’s impression are automatically given a negative score, which means they are more close to women in word vectors. Therefore, we conduct further analysis by separating the data into two groups based on the neutral line in AGSS.

| CBOW | CWE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0.673 | 0.628 | ||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| CBOW | CWE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0.036 | 0.020 | ||

| p-value | 0.543 | 0.724 |

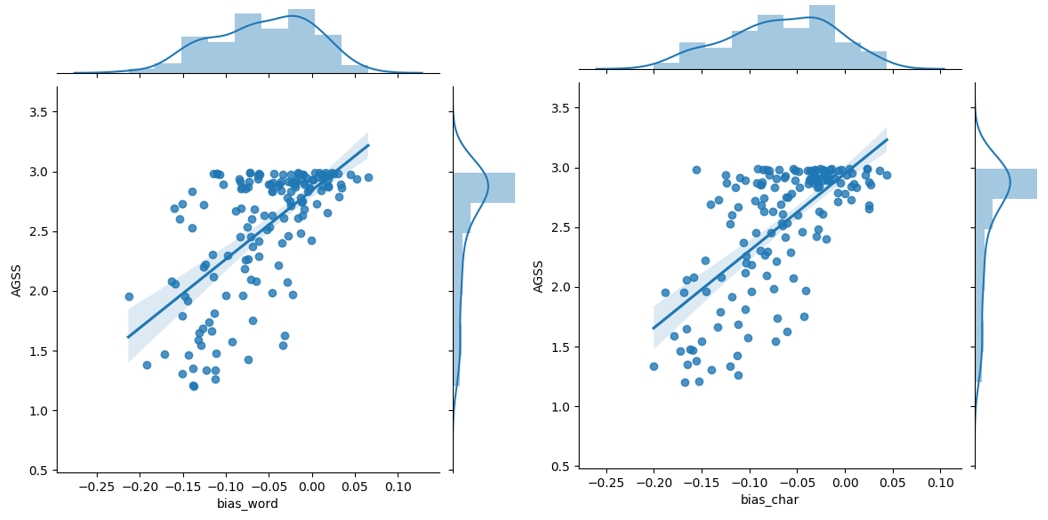

We recalculate the Pearson correlation coefficients for the two group of data, presenting results in Table 7 and Table 8. To give a full picture, separated scatter plots as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 are also included. The increment of coefficients for the group with AGSS scores lower than 3 suggests that most adjectives believed for describing women are closer to females in word vectors as well. What is encoded by word embedding is consistent with people’s impressions of these words. In addition, the correlation for scores from vectors trained with CBOW exceeds the results with the CWE model. This finding might indicate the underlying negative influence of covering character-level information in the word embedding.

However, a substantial divergence appears in the other group. Based on the scatter plot and the Pearson coefficient, some of the adjectives that almost exclusively connect with male in people’s minds could be very neutral according to our word embedding. The coefficients also suggest that the two categories of data do not show linear relations. Additionally, only one-third of the adjectives in this group are closer to males in word embedding, while the others are actually more associated with females. Obviously, what we estimate from embedding disagrees with people’s attitudes. This could be explained by the development of language. The study of Zhu and Liu (2020) proves that some Chinese adjectives for describing men in past time gradually become neutral in written language. Since the language used online develops fast and our training data are online news reports, the word embedding we trained is likely affected by the change. However, the public has not realized such development although they might start to use it in the new way. Therefore, when they are queried about the attitude towards attitudes, they might give an answer based on their outdated knowledge.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we investigate gender bias in Chinese word embeddings from the perspective of adjectives, and compare automatically calculated gender bias score with human attitudes. We elaborately present the differences between gender bias encoded in word vectors and the people’s feeling of the same adjective. For the words that people believe for describing women, the extracted score of gender bias gives an identified results; while for adjectives that should be used for men in people’s mind, our results suggest that these group of words are actually more neutral than the crowd judgement. Additionally, how the word embedding models covering character-level information perform in terms of capturing gender bias in Chinese is also examined.

Acknowledgments

This project grew out of a master course project for the Fall 2020 Uppsala University 5LN714, Language Technology: Research and Development. We would like to thank Sara Stymne and Ali Basirat for some great suggestions and the anonymous reviewers for their excellent feedback.

References

- Baker (2013) Paul Baker. 2013. Will ms ever be as frequent as mr? a corpus-based comparison of gendered terms across four diachronic corpora of british english. Gender and Language, 1(1).

- Bojanowski et al. (2017) Piotr Bojanowski, Edouard Grave, Armand Joulin, and Tomas Mikolov. 2017. Enriching word vectors with subword information. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 5:135–146.

- Bolukbasi et al. (2016) Tolga Bolukbasi, Kai-Wei Chang, James Y Zou, Venkatesh Saligrama, and Adam T Kalai. 2016. Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker? debiasing word embeddings. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 4349–4357.

- Caliskan et al. (2017) Aylin Caliskan, Joanna J Bryson, and Arvind Narayanan. 2017. Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases. Science, 356(6334):183–186.

- Chen et al. (2015) Xinxiong Chen, Lei Xu, Zhiyuan Liu, Maosong Sun, and Huanbo Luan. 2015. Joint learning of character and word embeddings. In Twenty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

- Garg et al. (2018) Nikhil Garg, Londa Schiebinger, Dan Jurafsky, and James Zou. 2018. Word embeddings quantify 100 years of gender and ethnic stereotypes. Proceedings of the National Academy of ences of the United States of America, 115(16):E3635.

- Hoyle et al. (2019) Alexander Miserlis Hoyle, Lawrence Wolf-Sonkin, Hanna Wallach, Isabelle Augenstein, and Ryan Cotterell. 2019. Unsupervised discovery of gendered language through latent-variable modeling. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 1706–1716.

- Lakoff (1973) Robin Lakoff. 1973. Language and woman’s place. Language in society, 2(1):45–79.

- Lewis and Lupyan (2020) Molly Lewis and Gary Lupyan. 2020. Gender stereotypes are reflected in the distributional structure of 25 languages. Nature human behaviour, pages 1–8.

- Li et al. (2018) Shen Li, Zhe Zhao, Renfen Hu, Wensi Li, Tao Liu, and Xiaoyong Du. 2018. Analogical reasoning on Chinese morphological and semantic relations. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), pages 138–143, Melbourne, Australia. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Madaan et al. (2018) Nishtha Madaan, Sameep Mehta, Taneea Agrawaal, Vrinda Malhotra, Aditi Aggarwal, Yatin Gupta, and Mayank Saxena. 2018. Analyze, detect and remove gender stereotyping from bollywood movies. In Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, pages 92–105.

- Menegatti and Rubini (2017) Michela Menegatti and Monica Rubini. 2017. Gender bias and sexism in language. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication.

- Mikolov et al. (2013a) Tomas Mikolov, Kai Chen, Greg Corrado, and Jeffrey Dean. 2013a. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space.

- Mikolov et al. (2013b) Tomas Mikolov, Ilya Sutskever, Kai Chen, Greg S Corrado, and Jeff Dean. 2013b. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 3111–3119.

- Pennington et al. (2014a) Jeffrey Pennington, Richard Socher, and Christopher Manning. 2014a. GloVe: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pages 1532–1543, Doha, Qatar. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Pennington et al. (2014b) Jeffrey Pennington, Richard Socher, and Christopher D Manning. 2014b. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP), pages 1532–1543.

- Prates et al. (2019) Marcelo OR Prates, Pedro H Avelar, and Luís C Lamb. 2019. Assessing gender bias in machine translation: a case study with google translate. Neural Computing and Applications, pages 1–19.

- Qi et al. (2018) Ye Qi, Devendra Sachan, Matthieu Felix, Sarguna Padmanabhan, and Graham Neubig. 2018. When and why are pre-trained word embeddings useful for neural machine translation? In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 2 (Short Papers), pages 529–535, New Orleans, Louisiana. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Sahlgren and Olsson (2019) Magnus Sahlgren and Fredrik Olsson. 2019. Gender bias in pretrained Swedish embeddings. In Proceedings of the 22nd Nordic Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 35–43, Turku, Finland. Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Wevers (2019) Melvin Wevers. 2019. Using word embeddings to examine gender bias in dutch newspapers, 1950-1990. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Computational Approaches to Historical Language Change, pages 92–97.

- Yu et al. (2017) Liang-Chih Yu, Jin Wang, K. Robert Lai, and Xuejie Zhang. 2017. Refining word embeddings for sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 534–539, Copenhagen, Denmark. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Zhang et al. (2018) Brian Hu Zhang, Blake Lemoine, and Margaret Mitchell. 2018. Mitigating unwanted biases with adversarial learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, pages 335–340.

- Zhao et al. (2017) Jieyu Zhao, Tianlu Wang, Mark Yatskar, Vicente Ordonez, and Kai-Wei Chang. 2017. Men also like shopping: Reducing gender bias amplification using corpus-level constraints. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 2979–2989.

- Zhao et al. (2018) Jieyu Zhao, Yichao Zhou, Zeyu Li, Wei Wang, and Kai-Wei Chang. 2018. Learning gender-neutral word embeddings. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 4847–4853.

- Zhu and Liu (2020) Shucheng Zhu and Pengyuan Liu. 2020. Great males and stubborn females: A diachronic study of corpus-based gendered skewness in chinese adjectives. In Proceedings of the 19th Chinese National Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 31–42.