Furstenberg set problem and exceptional set estimate in prime fields: dimension two implies higher dimensions

Abstract.

We study Furstenberg set problem, and exceptional set estimate for Marstrand’s orthogonal projection in prime fields for all dimensions. We define the Furstenberg index and the Marstrand index .

It is shown that the two-dimensional result for Furstenberg set problem implies all higher dimensional results.

Key words and phrases:

Furstenberg problem2020 Mathematics Subject Classification:

28A75, 28A781. Introduction

We study the Furstenberg set problem, as well as the exceptional set estimate in prime fields. The main novelty of this paper is that we prove, for these two problems, the two-dimensional result implies all higher dimensional results. In common sense, high dimensional version is harder than low dimensional version. For example, a closely related problem—Kakeya conjecture is known for dimension two but wide open for dimension bigger than two. Hence, it is surprising that for these two problems in prime fields, all higher dimensional results can be deduced from the two dimensional result.

1.1. Background

We first introduce the two problems—Furstenberg set problem and exceptional set estimate in Euclidean space.

1.1.1. Furstenberg set problem

The Furstenberg set problem was originally considered by Wolff [16] in . Fix . We say is a -set in , if is of the form

where is a set of lines with and for each there exists with . ( will always mean Hausdorff dimension.) Furstenberg set problem asks about the optimal lower bound on the Hausdorff dimension of -sets, i.e.,

Recently, Ren and Wang [15] resolved the Furstenberg set problem by proving

| (1) |

For more reference and the history on this problem, we refer to [15], [13].

Furstenberg set problem was also considered in higher dimensions, see for example [5], [1], [7]. It can be formulated similarly as follows.

Fix integers . Fix . We say is a -set in , if is of the form

where is a set of -planes with and for each there exists with . Furstenberg set problem in for -planes asks to compute

The Furstenberg set problems in higher dimensions remains wide open.

1.1.2. Exceptional set estimate

Next, we introduce the problem of exceptional set estimate. We first introduce this problem over . The projection theory dates back to Marstrand [8], who showed that if is a Borel set in , then the projection of onto almost every one-dimensional subspace has Hausdorff dimension . This was generalized to by Mattila [9] who showed that if is a Borel set in , then the projection of onto almost every -dimensional subspace has Hausdorff dimension .

One can consider a refined version of the Marstrand’s projection problem, which is known as the exceptional set estimate.

For , we use to denote the orthogonal projection. For and , we define the exceptional set

The exceptional set estimate is about finding optimal upper bound of (in terms of ), i.e.,

In , D. Oberlin [10] conjectured that for and with , one has the following exceptional set estimate

| (2) |

This conjecture was proved by Ren and Wang in [15].

1.2. The problems in prime fields

In the rest of the paper, we only look at prime fields. Let be a prime and be the prime field with elements. Throughout the paper, means for some large constant (independent of ). means both and . means for a large constant (independent of ). means both and .

1.2.1. Furstenberg set problem

Definition 1 (-set).

Fix integers , and numbers , . Let . We say is a -Furstenberg set (over ), if is a subset of of form

Here, is a set of -planes with ; for each , is a subset of with .

Remark 2.

We remark that are important parameters, while is not. Since is not an important parameter, from now on, we will drop from notation and simply call -set as -set, thinking of as a constant in .

We make the following definition.

Definition 3.

We say is admissible, if are integers and , .

The Furstenberg set problem can be formulated as:

Question 1.

Suppose is admissible. Find the largest , so that

| (3) |

holds for any .

The in the above inequality is actually . We just view as fixed parameters, so we simplify it to . The crucial point is that the implicit constant in or throughout this paper never depends on , but can depend on any other fixed parameters. We are interested in the behaviour as goes to infinity, so the goal is to find the index for fixed .

We see the problem consists of two parts: for fixed ,

-

(1)

(Lower bound) show for any -set , we have ;

-

(2)

(Upper bound) show the existence of a -set , such that .

Based on the Ren-Wang’s result (1), it is reasonable to make the conjecture in .

Conjecture 4.

Fix . Then for any -set over , we have

for any .

Remark 5.

It is crucial to use prime field . Otherwise, the conjecture fails. Consider the problem in , where is the square of a prime. We choose the set of lines , so and hence . For each line in , define , so and hence . One can calculate . However, .

Usually, people believe the problem in finite field is easier than in Euclidean space. However, Conjecture 4 remains open, while Euclidean version have been resolved.

In the paper, we explicitly find the function . The definition for is tricky, so we postpone it later in Definition 11. The following are main results.

Theorem 6 (Upper bound).

Suppose is admissible. Then for any prime , there exits a -set over , such that

Theorem 7 (Lower bound).

1.2.2. Exceptional set estimate

We also study the exceptional set estimate in prime fields in all dimensions. We show that the two-dimensional result for Furstenberg set problem implies all higher dimensional results for exceptional set estimates.

To define the projection in , we first consider an equivalent definition of projection in .

Recall is the orthogonal projection. For , we also define the map

as . We see that is the unique -plane in that is parallel to and passes through . It is not hard to see that and are the same things. This motivates the definition of projections in . We will still use the notations for (which have been used for in previous subsection). This will not cause any confusion.

Definition 8 (Exceptional set).

For , define

as .

Suppose . Let . We define

(We remark that also depends on , but for simplicity, we drop from the notation.)

We explicitly find the function , whose definition is tricky and therefore postponed to Definition 14. We state the following results.

Theorem 9 (Lower bound).

Fix , and . Then for large enough, there exists with , such that

| (4) |

Theorem 10 (Upper bound).

Assume Conjecture 4 holds. Fix , and . If is large enough, then for any with , we have

| (5) |

for any .

1.3. Strategy of the proof

The proof of Theorem 6 and Theorem 9 is by constructing examples. The proof of Theorem 7 and Theorem 10 is by a sequence of pigeonholing arguments and induction on both and . We explain the idea of the proof of Theorem 7.

We consider the case . Suppose for any -set , we have . The goal is to prove for any -set , . We will carefully analyze the structure of and find subsets of which are -set. Then we use the estimate for those -sets.

Write , where with and with . Project to , and partition according to their images. For each , define to be the set of those whose image under the projection is . We may assume all the lines in are not parallel to (by throwing away a small portion of ). We obtain the partition

By pigeonholing, we can find so that are comparable for all . Moreover, denoting , , we may assume .

Next, we look at

This is a -set in . By hypothesis, we have

We write

By pigeonholing on , we may assume there is a subset so that are comparable for . Moreover, denoting , , we may assume

Also, we may assume are the same for all by doing another pigeonholing on . We can also assume a strong condition on : . But we do not expand the discussion here.

It turns out that the worst scenario for is when

This will be made precise in the latter sections, so we do not expand the discussion here.

Now, we have

Note that is a -set. Hence

The problem boils down to the following linear programming problem: suppose

| (6) |

Show that

The proof of the last inequality will be done by brutal force.

1.4. Structure of the paper

In Section 2, we define and prove some fundamental lemmas. In Section 3, we prove Theorem 6. In Section 4 and 5, we prove Theorem 7. In Section 6, we prove Theorem 9. In Section 7 and 8, we prove Theorem 10.

Acknowledgement. The author would like to thank Larry Guth, Bochen Liu, Hong Wang and Shukun Wu for some helpful communications.

2. Preliminary

2.1. Definition of and

Definition 11 (Furstenberg index).

Suppose is admissible, we define as follows.

(a) If , define

| (7) |

(b) If , write where . If also , define

| (8) |

If we are not in Case (a) and (b), then and , we write

| (9) |

where , , , .

(c) If , define

| (10) |

(d) If , define

| (11) |

Remark 12.

Through this definition, we can calculate for . One sees that Conjecture 4 is equivalent to saying that .

The following is a construction of -set, which provides evidence on why Conjecture 4 should be reasonable.

Proposition 13.

For , there exists a -set such that

| (12) |

For . there exists a -set such that

| (13) |

Proof.

When , we construct as follows. If , choose to be a set of lines passing through and . Then . If , we choose points on , and for each , we choose lines through that are not parallel to . If the line is through , then we let . We see that is a -set with cardinality . (Here, should actually be the integer , but we still write it as for simplicity, thinking of it as an integer. Same convention applies in the whole paper.)

Consider the case when . There are three terms in the “min” on the RHS of (13). We note that: when , minimum achieves at ; when , minimum achieves at ; when , minimum achieves at .

-

(1)

If is a -set, then .

-

(2)

Choose to be a set of lines that are not parallel to the line . Let . Then is a -set with . Therefore, .

-

(3)

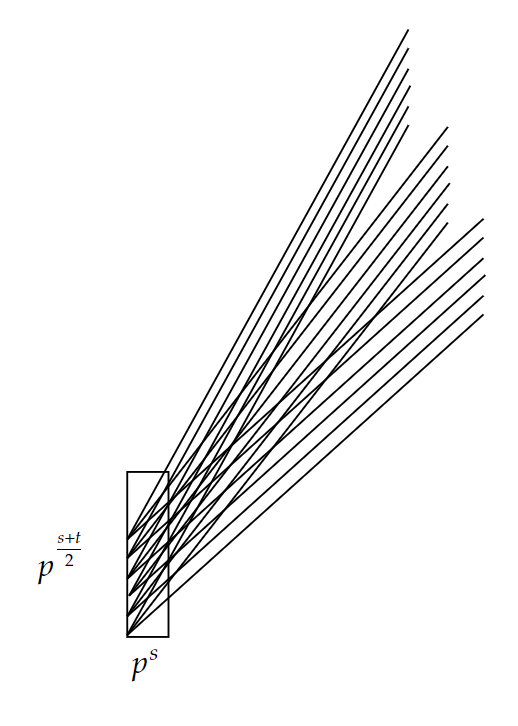

It remains to consider the case when . This example is of Szemerédi-Trotter type. The heuristic is shown in Figure 1, where we have directions and for each direction, there are lines. We also have a rectangle of size . The rectangle intersects each line at points, which is defined to be . We also see is contained in the rectangle. Therefore, .

Let . Here, we view as elements in , and hence as a line in . For each , let . We see that is contained in . Therefore, .

∎

Next, we define the index for Marstrand’s orthogonal projection.

Definition 14 (Marstrand index).

Let be integers. Let . We make the following definition for . We write where and . For convenience, we call such expression of canonical.

Type 1: If , define

| (14) |

Type 2: If , and , define

| (15) |

Type 3: If , and , define

| (16) |

Type 4: If , define

| (17) |

Remark 15.

corresponds to the case when exceptional set is empty. We remark that in the Euclidean setting, the empty set is assumed to have dimension , in order to satisfy a Fubini-type heuristic .

One can check, when ,

| (18) |

We discuss a construction of exceptional set.

Proposition 16.

Let , . Then for large enough, there exists with , such that

Proof.

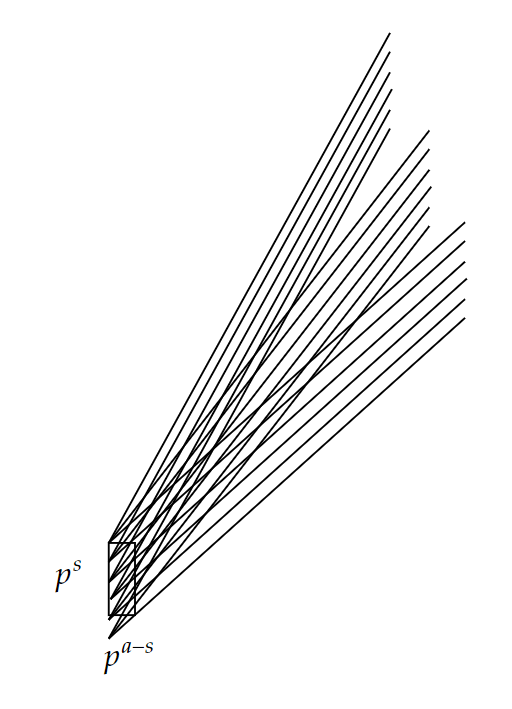

The heuristic is shown in Figure 2. Our set is the lattice points in the rectangle of size . For any slope , we are able to find lines with slope to cover . Hence, this slope- direction belongs to the exceptional set.

Consider the set . For , we use to denote the line . We claim that for each ,

Note that if and , then , which means there exists such that . Hence, . This means .

We see that , and has cardinality . ∎

2.2. Useful lemmas

We prove several useful lemmas, which will be used in the later proof. We suggest the reader to skip this part in the first reading.

Lemma 17.

Suppose is the set of -dimensional subspaces in , is the set of -planes in . We have:

-

(1)

;

-

(2)

;

-

(3)

Fix integers with . Let . Then .

Proof.

(1) and (2) are fundamental. We prove (3). is a -plane means intersects transversely. (3) agrees with the intuition in , since generic intersect transversely. Noting (2), we see that it suffices to prove

| (19) |

for . The proof of (19) is as follows. Choose a -plane in . There are choices for . If , then . We have choices for such that . The two estimates give (19). ∎

Lemma 18.

Let , be integers satisfying and . If , then

Proof.

By definition

The latter set is

It suffices to show for ,

| (20) |

On the one hand, the LHS is

| (21) |

On the other hand, for fixed , we have

| (22) |

One can check . has cardinality

| (23) |

In the last line, we use . Therefore,

Lemma 19.

Suppose is admissible, then

Proof.

It is easy to check , so we just need to check . We check four cases as in Definition 11.

(a) If , this is true by definition.

(b) If , write If , then

(d) In the final case, we have

To show it is is equivalent to show

This is true since and . ∎

Lemma 20.

Suppose is admissible, . Then

Proof.

This is equivalent to showing that for fixed , the map is Lipschitz with Lipschitz constant . We sketch the proof. First, it is not hard to show is continuous. Since is piecewise defined, we check each formula of . We see the derivative on is . ∎

is continuous in , but not in . Nevertheless, we can still say something about .

Lemma 21.

is locally left-Lipschitz in . In other words, if we write (), we have

for any .

Proof.

We just note that is defined piecewise for in left-open intervals of form where . Moreover, is Lipschitz in each of these left-open intervals. ∎

The next results are for the Marstrand index.

Lemma 22.

Each pair satisfying belongs to exactly one of the four types in Definition 14.

Proof.

To show this, we just need to prove for a fixed , the ranges of determined by four cases form a partition of . Type 1 corresponds to . Type 4 corresponds to . Note that , so we just need to show the ranges of determined by Type 2 and Type 3 from a partition of . Since the ranges of determined by Type2 and Type 3 are disjoint, we just need to show

We first show “. Suppose satisfies the condition in Type 2. We want to show , which is equivalent to . This is true since and . Suppose satisfies condition in Type 3. Again, we want to show . This is true since and .

Next, we show “”. Suppose . implies

implies

If , then . Hence, satisfies the condition in Type 2. If , then . Hence, satisfies the condition in Type 3. ∎

Lemma 23.

For and that are in the domain of and , we have

Proof.

Let be the canonical expression. We just check four types as in Definition 14.

Type 1: If , then

Type 4: If , then we have .

Type 2: Suppose is of Type 2.

If .

If , then . So, is of Type 3. We have the same estimate:

Note that the integer part is reduced to , so we can keep doing the iteration.

Type 3: This is similar to Type 2, so we just omit the proof.

∎

Lemma 24.

Proof.

The proof is simply by checking when is of Type 2 or Type 3. ∎

We also show two easy results about exceptional set estimate.

Lemma 25.

Recall Definition 14. Suppose we are in Type 1: . Then there exists with , such that

Proof.

We just choose to be any set with cardinality . One can check by definition that . ∎

Lemma 26.

Recall Definition 14. Suppose we are in Type 4: . Then for any with , we have

Proof.

If , then

a contradiction! Therefore, . ∎

3. Furstenberg set problem: upper bound

In this section, we prove Theorem 6. In other words, we will construct a -set , such that

3.1. Two special cases

To get familiar with , we discuss two special cases: ; .

When , we can morally view as . Therefore, a -set is of form

Estimating the size of is known as the “union of -planes problem”. It has been resolved in finite fields by R. Oberlin [11]. The Euclidean version was resolved by the author in [3].

When , this is the Furstenberg set problem for lines. To construct a -set

with size as small as possible, we hope the lines in are compressed in low dimensional space. Write , where is an integer and . Since , we can make contained in . Therefore, our goal becomes to construct a small -set. The trick is to take Cartesian product of a -set with . Let be a -set and has the form

We will construct a -set based on . Let be the projection onto the first two coordinates. Define to be the set of lines in such that is a line in . Then, . If , then . We define . We see that , so

is a -set. Also, since , we have

By checking Definition 11, one exactly sees that

3.2. Proof of Theorem 6

For admissible , we will construct a -set

such that

Case (a):

If , we choose to be -planes pass through the origin , and . Then . Here, means .

If , we choose points in . For each such point , we choose -planes that pass through , and require the -planes to be transverse to . We obtain -planes which is . If pass through , we set . We see that .

Case (b):

We write , where . The construction is similar to Case (a). We choose many -planes that contain . This is doable since

Let be these -planes. Fix with . For each , let . We see that .

Case (c):

We write

| (24) |

where , , , . We remark that here we allow , though we assumed in the canonical expression. Allowing will produce the example in Case (d).

We write . Note that fraction of -planes intersect at a -plane. Heuristically speaking, to make as small as possible, we would like to be a subset of . For simplicity, we write as , thinking of it as a subspace of . This will not cause any ambiguity.

Note that for each , the cardinality of

is . We just need to find with , and for each , to find with , such that

| (25) |

If this is done, then we let be those -planes that contain some , and if . We see that , and hence is a -set. Also, we have the upper bound

It suffices to find a -set such that (25) holds. Note that and . We will construct the -planes so that they lie in . It suffices to find a -set such that (25) holds.

Next, we define which is a subset of . And for each , define . We see that , . We also see that is contained in , and hence

Finally, we define . For each , consider the -plane . Let be the projection (naturally defined). We let be the set of -planes contained in such that . Note that fraction of the -planes in lie in , so .

We define (actually this is a disjoint union). For , define . We see that , and . Hence, is a -set. Since , we have

The construction is done.

Case (d)

We still use (24), but the range of is . Note the worst case is when . What we need to do is, for

| (26) |

construct a -set such that

The trick is to still use the construction in Case (c), with replaced by and replaced by . Therefore, we can construct a -set such that

4. Furstenberg set problem: Lower bound I

To get more familiar with the problem, we first prove two special cases of Theorem 7: ; .

Proposition 27.

If is a -set, then

Proof.

Suppose . Note that each can lie in at most different . We have

Hence, . Also, trivially, . ∎

Proposition 28.

If is a -set, then

Proof.

By the definition of -set, . ∎

In this section, we prove Theorem 7 for . The proof is by induction on . The goal of this section is to prove the following result.

Proposition 29.

Let and . Suppose for admissible , we know

| (27) |

for any . Then for admissible , we have

| (28) |

for any .

We first prove the following lemma.

Lemma 30.

Assume (27) holds. Suppose is admissible. Then for any -set , there exist numbers , such that

| (29) |

and

| (30) |

and

| (31) |

Proof.

We will do several steps of pigeonholing, which lead to the parameters .

By the definition of -set, we write

where with , and with .

The strategy is to find a subset of , and a subset of for each , still denoted by , , so that the new satisfy certain uniformity. This is done by a sequence of pigeonhole arguments.

By properly choosing the coordinate, we can assume fraction of the -planes in are not parallel to . Throwing away some , we can just assume all the -planes in are not parallel to .

Now, we partition according to . Since each is not parallel to and the ambient space is , must intersect at a -plane. For each , we define to be the set of such that is parallel to . We obtain a partition

First pigeonholing. We assume there exists with such that for each , . Here, are dyadic numbers and

| (32) |

(Recall means .) We still use to denote . And we see that

Second pigeonholing. By properly choosing the coordinate and throw away fraction of in , we can assume each in satisfies . Denote . If and , then is a line. We denote it by . Note that is not parallel to the first coordinate in .

For a fixed , we do a Fubini-type argument. Write

Noting that , by pigeonholing, we find a subset , so that , and for each , . Here, are dyadic numbers and satisfy

By throwing away some horizontal slices of , we can assume

For the new , we still have

For convenience, given and , we denote

is called the horizontal -slice. (Note that there is no confusion, since uniquely determines .) Thus, we have

| (33) |

Third pigeonholing. For each , we can find dyadic numbers so that fraction of in satisfy .

Fourth pigeonholing. There exist dyadic numbers such that fraction of in satisfy and .

We summarize what we have done so far. We can redefine , and , so that and the following uniformity holds.

For and each ,

| (34) |

with and for each , .

Fix a . We want to estimate . This is some sort of Furstenberg set in two-dimensional space. Also, an important preperty is that each is not parallel to the first coordinate. We will exploit some “quasi-product” structure of this set.

Lemma 31.

Assume Conjecture 4 holds. Suppose is a -set. Also, we assume each is not parallel to . Then there exist dyadic numbers such that

and

for any . Also, contains a subset of form

where with , and with .

Proof.

For , define . By pigeonholing on horizontal slices of , we can find so that for all , have comparable cardinality. We may denote for two dyadic numbers . We can also assume . Hence, assuming Conjecture 4, we have

However, we still need the condition . This is handled by the following trick. We will conduct an algorithm to find a sequence , and disjoint subsets of . To start with, let . By pigeonholing, we can find , such that , for each , and

Suppose we have defined for . If , then we define

Since each is not parallel to , we see that is still a -set. By the same pigeonholing, we find , so that , for each , and

If , then we stop and let .

The algorithm will stop in finite steps. Denote . Let be dyadic numbers so that , . For each , let be a subset of with . This is doable, since if . One can check

This is proved in the following way. Suppose , then

Also, one can check

∎

Return back to (which lie in ). Recall and . We see that is a -set, for any . Here, .

By Lemma 31, there exist dyadic numbers , so that contains a subset of form

Here, with ; and with . We also have

By pigeonholing on again, we can throw away some so that the cardinality of is still , and assume there exist such that

and

By Lemma 20,

Finally, we are about to estimate the lower bound of the cardinality of This is not the original one, but the one after pigeonholing. Recall (34), we have

| (35) |

We define

Then is contained in the -plane .

If , then

Recall that

We have

The reader can check, for fixed , lies in .

Now we see that

We want to estimate the lower bound of the right hand side. Intuitively, one can imagine the worst case is when are morally the same for all ; otherwise we may translate them to the same -th coordinate so that their union becomes smaller. For example, if we have sets (). Then is the smallest when all the are the same.

Let us return to the estimate of

There are two lower bounds. The first lower bound is obtained from a fixed . We have

For the second lower bound, we will estimate on each -slice. We define the -slice of by

We will see that is some sort of -set. Define

We note two bounds for :

| (36) |

| (37) |

We used that , , .

We claim that the right hand side is

By pigeonholing, we can find a dyadic number and , so that for and

Hence,

We can estimate

By Lemma 20, we have

∎

The next lemma is a recursive inequality of , which can be used to bound the right hand side of (31).

Lemma 32.

Suppose is admissible. Suppose there exist numbers , such that

| (38) |

and

| (39) |

Then,

| (40) |

Proof of Proposition 29 assuming Lemma 30 and Lemma 32.

Fix , where with . We just need to prove

| (41) |

for any -set . Here, is a large number.

We only need to prove for large enough , since for small we can choose the constant to be large.

Suppose (27) holds. Then in particular, Conjecture 4 also holds. If is a -set, by Lemma 30, there exist numbers , such that

| (42) |

and

| (43) |

and

| (44) |

Here, we used the fact that when is large enough (depending on ), then implies . Also, by our assumption. . Let . .

Since , we can find and , so that , . Now we have

| (45) |

and

| (46) |

and

| (47) |

In the last inequality, we used Lemma 20.

In summary, we finish the proof of

∎

It remains to prove Lemma 32. It can be reduced to the following lemma, with “” in (39) all replaced by “”.

Lemma 33.

Suppose is admissible. Suppose there exist numbers , such that

| (48) |

and

| (49) |

Then,

| (50) |

Proof of Lemma 32 assuming Lemma 33.

For , we can find , so that . It is slightly trickier to modify . Noting that , we can find so that . Now we can apply Lemma 33 to the numbers . We obtain

Since the new numbers are smaller than the old numbers and by using the monotonicity of , we have

∎

It remains to prove Lemma 33.

Proof of Lemma 33.

For convenience, we recall the definition of Furstenberg index in the special case .

(a) If ,

(b) If , write . If also ,

If we are not in Case (a) and (b), then and , we write

where , , .

(c) If ,

(d) If ,

Let us denote

Our goal is to prove

When , then . We want to prove . Trivially, . Also,

Using and , we obtain

When , we have

So we consider and . Write

where , , . In this case,

We just need to show either , or , or .

We first analyze . This is done by discussing the values of .

Case (a): By definition, we have . Since and , we have . We have

Recall . We have

If , then . If , then , by Lemma 20. Therefore, we have

The last inequality is because .

Case (b) We have

Subcase (b.0): In this case, , . We have

The last inequality is because

Subcase (b.1): We have

since .

Subcase (b.2): We have

Since

Subcase (b.3): We have

Case (c): , We write for . Since , we have .

Subcase (c.I): We have . We have

| (51) |

Subsubcase (c.I.1): We have

| (52) |

Subsubsubcase (c.I.1.0): Then . We have

Subsubsubcase (c.I.1.1): We have

Subsubsubcase (c.I.1.2): We have

We also have

Combining together gives

Subsubsubcase (c.I.1.3): We have

SubSubcase (c.I.2): We have

Subsubsubcase (c,I.2.0): Then . We have

Subsubsubcase (c.I.2.1): We have

Here, we used .

Subsubsubcase (c.I.2.2): We have

To prove , it suffices to prove

This is true since .

Subsubsubcase (c.I.2.3):

Subsubcase (c.I.3): We have

Subcase (c.II): We write . We have

The discussion is the same as Subcase (c.I), since we did not use the condition .

Subcase (d): We have

Therefore,

∎

5. Furstenberg set problem: Lower bound II

Proposition 34.

Let and . Suppose for any and admissible , we know

| (53) |

for any . Then for admissible , we know

| (54) |

for any .

We prove the following lemma.

Lemma 35.

Assume (53) holds. Suppose is admissible and . Then for any -set , there exist numbers , such that

| (55) |

and

| (56) |

and

| (57) |

Proof.

We will do several steps of pigeonholing, which lead to the parameters .

By the definition of -set, we write

where with , and with .

The strategy is to find a subset of , and a subset of for each , still denoted by , , so that the new satisfy certain uniformity. This is done by a sequence of pigeonhole arguments.

By properly choosing the coordinate, we can assume fraction of the -planes in are not parallel to the -th axis . Throwing away some , we can just assume all the -planes in are not parallel to with still satisfying . Because of this, we see that for any , the projection of onto , denoted by is a -plane in .

Now, we partition according to . For each , we define to be the set of such that . We obtain a partition

First pigeonholing. We assume there exists with such that for each , . Here, are dyadic numbers and

| (58) |

The upper bound for is because , and . We still use to denote . And we see that

Fix a . We want to estimate . This is some sort of Furstenberg set for -planes in -dimensional space. Also, an important preperty is that each is not parallel to the last coordinate. Therefore, any line parallel to will intersect at a single point. We will exploit some “quasi-product” structure of this set.

Lemma 36.

Assume (53) holds for . Suppose is a -set. Also, we assume each intersects at a single point. Then there exist dyadic numbers such that

and

for any . Also, contains a subset of form

where with , and with .

Proof.

For , define . By pigeonholing on vertical slices of , we can find so that for all , have comparable cardinality. We may denote for two dyadic numbers . We can also assume . Hence, assuming (53) holds for , we have

However, we still need the condition . This is handled by the same trick as in the proof of Lemma 31. We will conduct an algorithm to find a sequence , and disjoint subsets of . To start with, let . By pigeonholing, we can find , such that , for each , and

Suppose we have defined for . If , then we define

Since each intersect (and hence ) at a single point, we see that is still a -set. By the same pigeonholing, we find , so that , for each , and

If , then we stop and let .

The algorithm will stop in finite steps. Denote . Let be dyadic numbers so that , . For each , let be a subset of with . This is doable, since if . One can check

This is proved in the following way. Suppose , then

Also, one can check

∎

Return back to (which lie in ). Recall and . We see that is a -set.

By Lemma 36, there exist dyadic numbers , so that contains a subset of form

Here, with ; and with . We also have

By pigeonholing on again, we can throw away some so that the cardinality of is still , and assume there exist such that

and

By Lemma 20, we have

Finally, we are about to estimate the lower bound of the cardinality of This is not the original one, but the one after pigeonholing. We write

| (59) |

Since , we see that

Since is a -set, by (53), we have

∎

The next lemma is a recursive inequality of , which can be used to bound the right hand side of (57).

Lemma 37.

Suppose is admissible and . Suppose there exist numbers , such that

| (60) |

and

| (61) |

Then,

| (62) |

Proof of Proposition 34 assuming Lemma 35 and Lemma 37.

Fix , where with . We just need to prove

| (63) |

for any -set . Here, is a large number.

We only need to prove for large enough , since for small we can choose the constant to be large.

Suppose (53) holds. If is a -set, by Lemma 35, there exist numbers , such that

| (64) |

and

| (65) |

and

| (66) |

Let which is by assumption. Choose for , so that . Choose , so that . Then satisfy the condition in Lemma 37, we obtain

By monotonicity of , Lemma 20 and Lemma 21, we have

∎

It remains to prove Lemma 37.

Proof of Lemma 37.

When , we have . By Lemma 19, we have

So we consider and . Denote

We have both

| (67) |

and

| (68) |

Write the canonical expression

| (69) |

where , , , . We have

Next, we analyze .

Case (1): We use

Since , we have

Therefore,

Therefore,

Case (2): We write , where . We have

Since , write

with .

Subcase (2.1): We have

Subsubcase (2.1.1): We have the canonical expression for :

Therefore,

Therefore,

We just need to show

To show , it suffices to show , s.t. . We can check:

.

.

.

Subsubcase (2.1.2): We write . We have

Therefore,

We just need to prove

This is not hard to verify by noting .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Subsubcase (2.1.3): We have , so

Therefore,

Also, . We see that since .

Subcase(2.2): Write where so that . We have

Here, the last line is the canonical expression for (see (9)), in which , .

If , then . By the same reasoning as in Subsubcase (2.1.3), we have .

Hence, we can assume We have

Since and , we have . If , then . We only need to consider two cases: .

We have

Subsubcase (2.2.1): When We have

where we used and .

We just need to check

A less obvious case will be . We leave out the verification of other cases.

Subsubcase (2.2.2): When Since , we have

Since , we have . Note that

We just need to prove

This is not hard to verify by noting . A less obvious case is .

∎

6. Exceptional set estimate: lower bound

We prove Theorem 9 in this section. The result in this section has been studied by the author [4] under the Euclidean setting, the statement there is slightly different from this paper. We still provide the details for the finite field setting, though they are essentially the same.

Proof of Theorem 9.

Recall that and was considered in Proposition 16. We denote to be the set constructed there which satisfies , and

Next, we prove for general . Note that Type 1 and Type 4 are easy, so we consider Type 2 and Type 3. Recall the canonical expression as in Definition 14: .

Type 2 We have . For , we only use . We first show the existence of with such that .

Choose , where has cardinality . For simplicity, we just write . We want to find those such that . We note that if satisfies , then , which means . This shows that

By Lemma 18, the right hand side has cardinality .

Type 3, We have . We show the existence of with such that .

We choose , where is such that and . We will use to denote . We use to denote . We use to denote the lines in . Define

It is not hard to see .

Let . We claim that if , then . In other words, satisfies . We first note that by definition , so

Therefore,

We see that may intersect with each other, so we delete a tiny portion from , so that the remaining part are disjoint with each other. Then we have

To make the argument precise, we first apply Lemma 18 to see

To calculate , we apply Lemma 18 again to see

and

Therefore, (when is large enough) and hence

Next we show for . By contradiction, suppose . By definition, satisfies

The first and third conditions imply . Similarly, the second and third conditions imply . Noting that , we have

which has cardinality , contradicting the fourth condition.

We have shown that , which has cardinality

Type 2, The trick is to write . Note that and . We apply the construction in “Type 3, ”, where we only used . We obtain a with such that

Type 3, The trick is to make bigger. We write . One can check and . We apply the construction in Type 2 with . We find with such that

Choosing any subset with , we get

∎

7. Exceptional set estimate: Upper bound I

We prove the following proposition in this section.

Proposition 38.

It is proved by using the following lemma.

Lemma 39.

Assume Conjecture 4 holds. Fix . Let and . Suppose the parameters satisfy and . Let with . Define

Then

Remark 40.

The implicit constant in can be made independent of , since we can apply the lemma to which consists values.

Proof.

The proof of this part is by Furstenberg estimate. As in Definition 14, write

| (71) |

There are four cases.

Type 1: When ,

Type 2: When and ,

Type 3: When and ,

Type 4: When ,

Type 1 is trivial, since is always true. Type 4 is also easy, since in this case we have , and hence . We only need to consider Type 2 and Type 3.

Suppose , we want to show

We write , where , .

For convenience, we define

| (72) |

Then in the case of Type 2 or Type 3.

Note that contains a -Furstenberg set . Since Conjecture 4 holds, by Theorem 7, we have the lower bound:

| (73) |

for any when is big enough depending on . We choose such that

From (73), there are three possible cases.

(1) .

This implies . Our goal is to show , so we just need to show

We also know

which implies

Since and , we have . Therefore, with the condition that , we see that

(2) .

In this case, , which implies

Since and , we get .

Now we want to prove . If this is not true, then by contradiction, we assume

This will imply

which is a contradiction, as .

(3) .

This is equivalent to . We hope to prove

We just need to prove

since .

This is equivalent to

We plug in . Then it suffices to prove

This inequality is equivalent to

This is easy to verify by checking either in case or in case . ∎

Proof of Proposition 38.

We will use the lemma that we just proved. We show that, if with , with , and is big enough, then there exists such that

Since , we have

For each and dyadic number , define

We see that form a partition of the of lines that are parallel to .

We choose , for example, . We will estimate the cardinality of the set for . We write with . By Lemma 39, we have

If we define

then

Summing over dyadic , we have

Therefore, when is large enough. We can find . In other words, there exists , such that for any ,

Now, we do the estimate. We have

Note that

In the last inequality, we are summing over terms and we assume is big enough.

We have

This implies .

∎

8. Exceptional set estimate: Upper bound II

The goal of this section is to prove the following proposition.

Proposition 41.

Let and . Suppose for any and , we have

| (74) |

for any . Then for , we have

for any .

We prove the following lemma.

Lemma 42.

Assume (74) holds. Suppose , , , and . Then for any with , there exist numbers , such that

| (75) |

and

| (76) |

Proof.

We will do several steps of pigeonholing, which lead to the parameters . For convenience, we denote .

By properly choosing the coordinate, we can assume fraction of the -planes in intersect transversely (at a -plane). Since we are going to find upper bound for , we can just assume all the planes in intersect at a -plane.

For each , we define . By pigeonholing, there exits with such that for each , . Here, are dyadic numbers so that

By pigeonholing on for , we can find a dyadic number and so that for any and

Since , we also have .

For each , we consider the slice . We denote . There exists a dyadic number , such that

for many . Here, is because for .

We see that contains a portion of when is large enough depending on . We can use (74) for the quadruple to obtain

By pigeonholing on , we can find such that

for all . And,

Next, we note that

By pigeonholing, there exists such that

We fix this and study the behavior of . Without loss of generality, we can assume . For , then . We see that is of form , where . Since , we have that is not parallel to .

Next, we project everything onto . For , we define

One can also check that .

Define . We see that is a subset of and .

The next important observation is that for any , , one has

This is not hard to verify once writing down the definition.

We can now do the estimate. By definition, for . Therefore,

This means that

Also, note that

By (74) with , we get

(It is crucial that we use instead of on the right hand side.)

Combining with the upper bound of , we get

Let . Since , we have .

Recall and note is decreasing in . By Lemma 23, we have

Therefore, under the new , we have

Next, we want to slightly increase to so that . By the condition , we have when is large enough. We just need to let . Noting and by Lemma 23 again, we have

We still use for . We obtain

∎

Lemma 43.

Suppose , , , and . Suppose there exist numbers , such that

| (77) |

Then

| (78) |

Proof.

Write ; in the canonical expressions. Since , there are only two choices for : or . Since , we have .

Case 1:

By Lemma 24,

Trivially,

Also, by Lemma 24,

It suffices to prove

Just need to note and .

Case 2:

Case 2.1:

Since and , we have . Hence,

Next we estimate . We claim we have

| (79) |

We just consider when . We note . If , then we use Type 3 in Definition 14, which gives the desired formula. If , we use Type 2, which gives , which is the same.

We also have .

When , we just need to prove

which is easy to verify, since and .

When , we just need to prove

Just need to check three scenarios:

(1) , since .

(2) , since .

(3) Their sum .

Case 2.2:

In this case, by Lemma 24,

It suffices to prove

We just use , since .

Case 2.3:

(We use instead of , since when , .)

Since ,

Also, we have

It suffices to prove

(1) , since implies , and .

(2) , since .

(3) , since .

Case 2.4:

When , it suffices to show

This is true by noting and .

When , it suffices to show

(1) , since and .

(2) , since .

(3) , since .

Case 3: The proof is similar to Case 1. By Lemma 24,

Trivially,

Also, by Lemma 24,

It suffices to prove

Just need to note and .

Case 4:

Case 4.1:

Since and , we have . Hence,

Next we estimate . As is Case 2.1,

| (80) |

We also have .

When , we just need to prove

which is easy to verify,since and .

When , we just need to prove

Just need to check three scenarios:

(1) , since .

(2) , since .

(3) , since .

Case 4.2:

In this case,

It suffices to prove

We just use , since .

Case 4.3:

Since ,

Also, we can assume ; otherwise, it .

Also, we have

When , we just need to prove

It is easy to verify .

When , it suffices to prove

(1) , since and .

(2) , since .

(3) , since .

Case 4.4:

We can also assume ; otherwise, it .

When , it suffices to show

This is true by noting and .

When , it suffices to show

(1) , since , .

(2) , since .

(3) , since .

Case 5:

Case 5.1:

In this case, we have

We assume

| (81) |

otherwise this is .

We also have . We just need to prove

Check three scenarios:

(1) , since and (since ).

(2) , since .

(3) , since .

Case 5.2:

In this case, by discussing or , we have

It suffices to prove

(1) , since .

(2) , since .

(3) , since .

Case 5.3:

There is nothing to do.

Case 5.4:

We assume

| (82) |

otherwise this is

It suffices to show

(1) , since and .

(2) , since .

(3) , since . ∎

References

- [1] D. Dabrowski, T. Orponen, and M. Villa. Integrability of orthogonal projections, and applications to Furstenberg sets. Advances in Mathematics, 407:108567, 2022.

- [2] K. J. Falconer. Hausdorff dimension and the exceptional set of projections. Mathematika, 29(1):109–115, 1982.

- [3] S. Gan. Hausdorff dimension of unions of -planes. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14544, 2023.

- [4] S. Gan. Exceptional set estimate through Brascamp-Lieb inequality. International Mathematics Research Notices, 2024(9):7944–7971, 2024.

- [5] K. Héra, T. Keleti, and A. Máthé. Hausdorff dimension of unions of affine subspaces and of Furstenberg-type sets. Journal of Fractal Geometry, 6(3):263–284, 2019.

- [6] R. Kaufman. On Hausdorff dimension of projections. Mathematika, 15(2):153–155, 1968.

- [7] L. Li and B. Liu. Orthogonal projection, dual furstenberg problem, and discretized sum-product. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.15784, 2024.

- [8] J. M. Marstrand. Some fundamental geometrical properties of plane sets of fractional dimensions. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 3(1):257–302, 1954.

- [9] P. Mattila. Hausdorff dimension, orthogonal projections and intersections with planes. Annales Fennici Mathematici, 1(2):227–244, 1975.

- [10] D. M. Oberlin. Restricted Radon transforms and projections of planar sets. Canadian Mathematical Bulletin, 55(4):815–820, 2012.

- [11] R. Oberlin. Unions of lines in . Mathematika, 62(3):738–752, 2016.

- [12] T. Orponen and P. Shmerkin. On the Hausdorff dimension of Furstenberg sets and orthogonal projections in the plane. Duke Mathematical Journal, 172(18):3559–3632, 2023.

- [13] T. Orponen and P. Shmerkin. Projections, Furstenberg sets, and the sum-product problem. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.10199, 2023.

- [14] Y. Peres and W. Schlag. Smoothness of projections, Bernoulli convolutions, and the dimension of exceptions. Duke Mathematical Journal, 2000.

- [15] K. Ren and H. Wang. Furstenberg sets estimate in the plane. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.08819, 2023.

- [16] T. Wolff. Recent work connected with the Kakeya problem. Prospects in mathematics (Princeton, NJ, 1996), 2(129-162):4, 1999.