Kyoto University, Kyoto, [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3244-6915 JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP20H05793, JP20K19742, JP21H03499 Kyoto University, Kyoto, [email protected] Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan and https://www.math.mi.i.nagoya-u.ac.jp/~otachi/ [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0087-853X JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP18H04091, JP18K11168, JP18K11169, JP20H05793, JP21K11752. \CopyrightKobayashi, Nagano, Otachi \ccsdesc[100]Mathematics of computing Discrete mathematics Combinatorics Combinatorial algorithms \relatedversion \EventEditorsJohn Q. Open and Joan R. Access \EventNoEds2 \EventLongTitle42nd Conference on Very Important Topics (CVIT 2016) \EventShortTitleCVIT 2016 \EventAcronymCVIT \EventYear2016 \EventDateDecember 24–27, 2016 \EventLocationLittle Whinging, United Kingdom \EventLogo \SeriesVolume42 \ArticleNo23

Finding shortest non-separating and non-disconnecting paths

Abstract

For a connected graph and , a non-separating - path is a path between and such that the set of vertices of does not separate , that is, is connected. An - path is non-disconnecting if is connected. The problems of finding shortest non-separating and non-disconnecting paths are both known to be NP-hard. In this paper, we consider the problems from the viewpoint of parameterized complexity. We show that the problem of finding a non-separating - path of length at most is W[1]-hard parameterized by , while the non-disconnecting counterpart is fixed-parameter tractable parameterized by . We also consider the shortest non-separating path problem on several classes of graphs and show that this problem is NP-hard even on bipartite graphs, split graphs, and planar graphs. As for positive results, the shortest non-separating path problem is fixed-parameter tractable parameterized by on planar graphs and polynomial-time solvable on chordal graphs if is the shortest path distance between and .

keywords:

Non-separating path, Parameterized complexity1 Introduction

Lovász’s path removal conjecture states the following claim: There is a function such that for every -connected graph and every pair of vertices and , has a path between and such that is -connected. This claim still remains open, while some spacial cases have been resolved [4, 15, 16, 22]. Tutte [22] proved that , that is, every triconnected graph satisfies that for every pair of vertices, there is a path between them whose removal results a connected graph. Kawarabayashi et al. [15] proved a weaker version of this conjecture: There is a function such that for every -connected graph and every pair of vertices and , has an induced path between and such that is -connected.

As a practical application, let us consider a network represented by an undirected graph , and we would like to build a private channel between a specific pair of nodes and . For some security reasons, the path used in this channel should be dedicated to the pair and , and hence all other connections do not use all nodes and/or edges on this path while keeping their connections. In graph-theoretic terms, the vertices (resp. edges) of the path between and does not form a separator (resp. a cut) of . Tutte’s result [22] indicates that such a path always exists in triconnected graphs, but may not exist in biconnected graphs. In addition to this connectivity constraint, the path between and is preferred to be short due to the cost of building a private channel. Motivated by such a natural application, the following two problems are studied.

Definition 1.1.

Given a connected graph , , and an integer , Shortest Non-Separating Path asks whether there is a path between and in such that the length of is at most and is connected.

Definition 1.2.

Given a connected graph , , and an integer , Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path asks whether there is a path between and in such that the length of is at most and is connected.

We say that a path is non-separating (in ) if is connected and is non-disconnecting (in ) if is connected.

Related work. The shortest path problem in graphs is one of the most fundamental combinatorial optimization problems, which is studied under various settings. Indeed, our problems Shortest Non-Separating Path and Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path can be seen as variants of this problem. From the computational complexity viewpoint, Shortest Non-Separating Path is known to be NP-hard and its optimization version cannot be approximated with factor in polynomial time for unless P NP [23]. Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path is shown to be NP-hard on general graphs and polynomial-time solvable on chordal graphs [18].

Our results. We investigate the parameterized complexity of both problems. We show that Shortest Non-Separating Path is W[1]-hard and Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path is fixed-parameter tractable parameterized by . A crucial observation for the fixed-parameter tractability of Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path is that the set of edges in a non-disconnecting path can be seen as an independent set of a cographic matroid. By applying the representative family of matroids [11], we show that Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path can be solved in time, where is the exponent of the matrix multiplication. We also show that Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path is OR-compositional, that is, there is no polynomial kernelization unless coNP NPpoly. To cope with the intractability of Shortest Non-Separating Path, we consider the problem on planar graphs and show that it is fixed-parameter tractable parameterized by . This result can be generalized to wider classes of graphs which have the diameter-treewidth property [9]. We also consider Shortest Non-Separating Path on several classes of graphs. We can observe that the complexity of Shortest Non-Separating Path is closely related to that of Hamiltonian Cycle (or Hamiltonian Path with specified end vertices). This observation readily proves the NP-completeness of Shortest Non-Separating Path on bipartite graphs, split graphs, and planar graphs. For chordal graphs, we devise a polynomial-time algorithm for Shortest Non-Separating Path for the case where is the shortest path distance between and .

2 Preliminaries

We use standard terminologies and known results in matroid theory and parameterized complexity theory, which are briefly discussed in this section. See [6, 20] for details.

Graphs. Let be a graph. The vertex set and edge set of are denoted by and , respectively. For , the open neighborhood of in is denoted by (i.e., ) and the closed neighborhood of in is denoted by (i.e., ). We extend this notation to sets: and for . For , we denote by the length of a shortest path between and in , where the length of a path is defined to the number of edges in it. We may omit the subscript of from these notations when no confusion arises. For , we write to denote the subgraph of induced by . For notational convenience, we may use instead of . For , we also use to represent the subgraph of consisting all vertices of and all edges in . For vertices and , a path between and is called a - path. A vertex is called a pendant if its degree is exactly .

Matroids and representative sets. Let be a finite set. If satisfies the following axioms, the pair is called a matroid: (1) ; (2) implies for ; and (3) for with , there is such that . Each set in is called an independent set of . From the third axiom of matroids, it is easy to observe that every (inclusion-wise) maximal independent set of have the same cardinality. The rank of is the maximum cardinality of an independent set of . A matroid of rank is linear (or representable) over a field if there is a matrix whose columns are indexed by such that if and only if the set of columns indexed by is linearly independent in .

Let be a graph. A cographic matroid of is a matroid such that is an independent set of if and only if is connected. Every cographic matroid is linear and its representation can be computed in polynomial time [20].

Our algorithmic result for Shortest Non-Disconnected Path is based on representative families due to [11].

Definition 2.1.

Let be a matroid and let be a family of independent sets of . For an integer , we say that is -representative for if the following condition holds: For every of size at most , if there is with such that , then there is with such that .

Theorem 2.2 ([11, 17]).

Given a linear matroid of rank that is represented as a matrix for some field , a family of independent sets of size , and an integer with , there is a deterministic algorithm computing a -representative family of size with

field operations, where is the exponent of the matrix multiplication.

Parameterized complexity. A parameterized problem is a language , where is a finite alphabet. We say that is fixed-parameter tractable (parameterized by ) if there is an algorithm deciding if for given in time , where is a computable function. A kernelization for is a polynomial-time algorithm that given an instance , computes an “equivalent” instance such that (1) if and only if and (2) for some computable function . We call a kernel. If the function is a polynomial, then the kernelization algorithm is called a polynomial kernelization and its output is called a polynomial kernel. An OR-composition is an algorithm that given instances of , computes an instance in time such that (1) if and only if for some and (2) . For a parameterized problem , its unparameterized problem is a language , where is a blank symbol and is an arbitrary symbol.

Theorem 2.3 ([3]).

If a parameterized problem admits an OR-composition and its unparameterized version is NP-complete, then does not have a polynomial kernelization unless coNP NPpoly.

3 Shortest Non-Separating Path

We discuss our complexity and algorithmic results for Shortest Non-Separating Path.

3.1 Hardness on graph classes

We obverse that, in most cases, Shortest Non-Separating Path is NP-hard on classes of graphs for which Hamiltonian Path (with distinguished end vertices) is NP-hard. Let be a graph and be distinct vertices of . We add a pendant vertex adjacent to and denote the resulting graph by . Then, we have the following observation.

For every non-separating path between and in , .

Suppose that for a class of graphs,

-

•

the problem of deciding whether given graph has a Hamiltonian path between specified vertices and in is NP-hard and

-

•

implies .

By Section 3.1, has a non-separating - path if and only if has a Hamiltonian path between and . This implies that the problem of finding a non-separating path between specified vertices is NP-hard on class .

Theorem 3.1.

The problem of deciding if an input graph has a non-separating - path is NP-complete even on planar graphs, bipartite graphs, and split graphs.

The classes of planar graphs and bipartite graphs are closed under the operation of adding a pendant. Recall that a graph is a split graph if the vertex set can be partitioned into a clique and an independent set . Thus, for the class of split graphs, we need the assumption that the pendant added is adjacent to a vertex in .

As the problem trivially belongs to NP, it suffices to show that Hamiltonian Path (with distinguished end vertices) is NP-hard on these classes of graphs111These results for bipartite graphs and planar graphs seem to be folklore but we were not able to find particular references.. For split graphs, it is known that Hamiltonian Path is NP-hard even if the distinguished end vertices are contained in the clique [19]. Let be a graph and let . We add a vertex that is adjacent to every vertex in , that is, and are twins. The resulting graph is denoted by . It is easy to verify that has a Hamiltonian cycle if and only if has a Hamiltonian path between and . The class of bipartite graphs is closed under this operation, that is, is bipartite. For planar graphs, may not be planar in general. However, Hamiltonian Cycle is NP-complete even if the input graph is planar and has a vertex of degree [14]. We apply the above operation to this degree- vertex, and the resulting graph is still planar. As the problem of finding a Hamiltonian cycle is NP-hard even on bipartite graphs [19] and planar graphs [14], Theorem 3.1 follows.

3.2 W[1]-hardness

Next, we show that Shortest Non-Separating Path is W[1]-hard parameterized by . The proof is done by giving a reduction from Multicolored Clique, which is known to be W[1]-complete [10]. In Multicolored Clique, we are given a graph with a partition of and asked to determine whether has a clique such that for each .

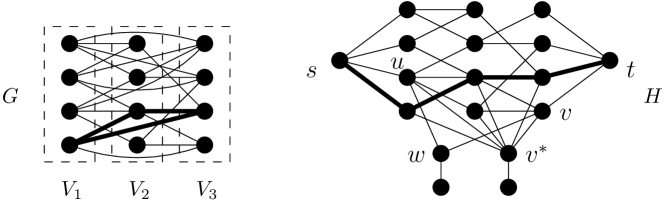

From an instance of Multicolored Clique, we construct an instance of Shortest Non-Separating Path as follows. Without loss of generality, we assume that contains more than vertices. We add two vertices and and edges between and all and between and all . For any pair of and with , we do the following. If , then we remove it. Otherwise, we add a path of length and a pendant vertex that is adjacent to the internal vertex of . Finally, we add a vertex , add an edge between and each original vertex , and add a pendant vertex adjacent to . The constructed graph is denoted by . See Figure 1 for an illustration of the graph .

Lemma 3.2.

There is a clique in such that for if and only if there is a non-separating - path of length at most in .

Proof 3.3.

Suppose first that has a clique with for . Then, is an - path of length in . To see the connectivity of , it suffices to show that every vertex is reachable to in . By the construction of , each vertex in is adjacent to in . Each vertex in is either the internal vertex of for some or the pendant vertex adjacent to . In both cases, at least one of and is not contained in as is a clique in , implying that is reachable to .

Conversely, suppose that has a non-separating - path of length at most in . By the assumption that has more than vertices, there is a vertex of that does not belong to . Observe that does not contain any internal vertex of some as otherwise the pendant vertex adjacent to becomes an isolated vertex by deleting , which implies has at least two connected components. Similarly, does not contain . These facts imply that the internal vertices of belong to , and we have for . Let . We claim that is a clique in . Suppose otherwise. There is a pair of vertices that are not adjacent in . This implies that contains the path . However, as contains both and , the internal vertex of together with its pendant vertex forms a component in , yielding a contradiction that is a non-separating path in .

Thus, we have the following theorem.

Theorem 3.4.

Shortest Non-Separating Path is W[1]-hard parameterized by .

3.3 Graphs with the diameter-treewidth property

By Theorem 3.4, Shortest Non-Separating Path is unlikely to be fixed-parameter tractable on general graphs. To overcome this intractability, we focus on sparse graph classes. We first note that algorithmic meta-theorems for FO Model Checking [12, 13] does not seem to be applied to Shortest Non-Separating Path as we need to care about the connectivity of graphs, while it can be expressed by a formula in MSO logic, which is as follows. The property that vertex set forms a non-separating - path can be expressed as:

where and are formulas in MSO2 that are true if and only if the subgraph induced by is connected and has a Hamiltonian path between and , respectively. We omit the details of these formulas, which can be found in [6] for example222In [6], they give an MSO2 sentence expressing the property of having a Hamiltonian cycle, which can be easily transformed into a formula expressing .. By Courcelle’s theorem [5] and its extension due to Arnborg et al. [1], we can compute a shortest non-separating - path in time, where is the number of vertices and is the treewidth333We do not give the definition of treewidth and (the optimization version of) Courcelle’s theorem. We refer to [6] for details. of . As there is an -time algorithm for computing the treewidth of an input graph [2], we have the following theorem.

Theorem 3.5.

Shortest Non-Separating Path is fixed-parameter tractable parameterized by the treewidth of input graphs.

A class of graphs is minor-closed if every minor of a graph also belongs to . We say that has the diameter-treewidth property if there is a function such that for every , the treewidth of is upper bounded by , where is the diameter of . It is well known that every planar graph has treewidth at most [21]444More precisely, the treewidth of a planar graph is upper bounded by , where is the radius of the graph., which implies that the class of planar graphs has the diameter-treewidth property. This can be generalized to more wider classes of graphs. A graph is called an apex graph if it has a vertex such that removing it makes the graph planar.

Theorem 3.6 ([7, 9]).

Let be a minor-closed class of graphs. Then, has the diameter-treewidth property if and only if it excludes some apex graph.

For that induces a connected subgraph , we denote by the graph obtained from by contracting all edges in and by the vertex corresponding to in . Since is connected, vertex is well-defined.

Lemma 3.7.

Let be a vertex subset such that is connected. Let be an - path in with . Then, is non-separating in if and only if it is non-separating in .

Proof 3.8.

Suppose first that is non-separating in . Let be arbitrary. As is non-separating, there is a - path in . Let be the vertex of such that if and if . Let be the vertex defined analogously. We show that there is a - path in as well. If does not contain any vertex in , it is also a - path in , and hence we are done. Suppose otherwise. Let and be the vertices in that are closest to and , respectively. Note that and can be the end vertices of , that is, may contain and . Let and (resp. ) be the subpath of between and (resp. and ). Then, the sequence of vertices obtained by concatenating after and replacing exactly one occurrence of a vertex in with forms a path between and . Since we choose arbitrarily, there is a path between any pair of vertices in as well. Hence, is non-separating in .

Conversely, suppose that is non-separating in . For , there is a path in . Suppose that neither nor . Then, we can construct a - path in as follows. If , is also a path in and hence we are done. Otherwise, . Let and be the subpaths in containing and , respectively. From and , we have a - path in by connecting them with an arbitrary path in between the end vertices other than and . Note that such a bridging path in always exists since is connected. Moreover, as and , this is also a - path in . Suppose otherwise that either or , say . In this case, we can construct a path between every vertex in and by concatenating and an arbitrary path in between and the end vertex of the subpath other than . Therefore, is non-separating in .

Now, we are ready to state the main result of this subsection.

Theorem 3.9.

Suppose that a minor-closed class of graphs has the diameter-treewidth property. Then, Shortest Non-Separating Path on is fixed-parameter tractable parameterized by .

Proof 3.10.

Let . We first compute . This can be done in linear time. If , then the instance is trivially infeasible. Suppose otherwise that . Let be a component in . By definition, every non-separating - path of length at most does not contain any vertex of . Let be the graph obtained from by contracting all edges in . For each component in , we denote by the vertex of corresponding to (i.e., is the vertex obtained by contracting all edges in ). Then, we have as and every vertex in is adjacent to a vertex in . By Lemma 3.7, has a non-separating - path of length at most if and only if so does . Since is minor-closed, we have and hence the treewidth of is upper bounded by for some function . By Theorem 3.5, we can check whether has a non-separating - path of length at most in time for some function .

3.4 Chordal graphs with

In Section 3.1, we have seen that Shortest Non-Separating Path is NP-complete even on split graphs (and thus on more general chordal graphs as well). To overcome this intractability, we restrict ourselves to finding a non-separating - path of length on chordal graphs.

A graph is choral if it has no cycles of length at least as an induced subgraph. In the following, fix a connected chordal graph .

Lemma 3.11.

Let be a vertex set such that is connected. For , every induced - path in satisfies that .

Proof 3.12.

Suppose to the contrary that an induced - path contains a vertex . Since starts and ends in , it contains a subpath such that and all other vertices in belong to . As and is connected, has an induced - path with all internal vertices belonging to . Since the internal vertices of have no neighbors in , induces a cycle. Both - paths and have length at least as and are not adjacent, and thus the cycle has length at least . This contradicts that is chordal.

For , a set of vertices is called a - separator of if there is no - path in . An inclusion-wise minimal - separator of is called a minimal - separator. A minimal separator of is a minimal - separator for some . Dirac’s well-know characterization [8] of chordal graphs states that a graph is chordal if and only of every minimal separator induces a clique.

Lemma 3.13.

Let be such that . If is an internal vertex of a shortest - path , then is an - separator of .

Proof 3.14.

Let . For , let

and . Let () be the index such that .

Suppose to the contrary that there is an induced - path such that . By Lemma 3.11, holds. Since starts in and ends in , there are indices and with such that consecutively visits a vertex and then a vertex in this order. Since and , at least one of and holds. By symmetry, we assume that .

If , then . In this case, we have and since otherwise admits a shortcut using the subpath . This implies that and . Since , we have and . This implies that , a contradiction

Next we consider the case . Recall that we also have as an assumption. In this case, we have as is not a shortcut for . Assume first that . By symmetry, we may assume that and . Since and , we have , a contradiction. Next assume that . That is, and . Since and is shortest, the vertices , , , , are distinct and form a cycle of length . Observe that since otherwise or is a shortcut. Similarly, . Hence, . Therefore, the possible chords for the cycle are and . In any combination of them, the graph has an induced cycle of length at least .

Let and be defined as in the proof of Lemma 3.13, and let . Note that each is a clique: if , then it is a singleton; otherwise, it is a minimal - separator of the chordal graph . Observe that if for all , then contains a unique shortest - path, and thus the problem is trivial. Otherwise, we define to be the minimum index such that and to be the maximum index such that . Since , we have .

Our algorithm works as follows.

-

1.

If contains a unique shortest - path , then test if is non-separating.

-

2.

Otherwise, find a shortest - path satisfying the following conditions.

-

(a)

does not contain a minimal - separator for and .

-

(b)

does not contain a minimal - separator for and .

-

(a)

Lemma 3.15.

The algorithm is correct.

Proof 3.16.

The first case is trivial. In the following, we prove the correctness of the second case.

First we show that the condition 2a is necessary. Let and . Since and , there is a vertex , where may be itself. Since , it holds that . Hence, and belong to the same connected component of . Since is a clique, . Thus, and belong to the same connected component of . Therefore, does not contain any - separator.

Next we show that the condition 2b is necessary. Let and . As before, it suffices to show that and belong to the same connected component of . By the same reasoning in the previous case, there are vertices and and they belong to the same connected component of . Now, since and , and belong to the same connected component of .

Finally we show that the conditions 2a and 2b together form a sufficient condition for to be non-separating. Assume that a shortest - path satisfies the conditions 2a and 2b. Since and , there is a connected component of that contains at least one vertex of . Now the condition 2a implies that (recall that ), and the condition 2b implies that holds. To complete the proof, it suffices to show that for all . If or , then . Let for some with . Observe that is an internal vertex of a shortest path from the unique vertex to the unique vertex . By Lemma 3.13, is a - separator. Since is connected and have neighbors in , contains a - path . Since is a - separator, contains a vertex such that

Therefore, has a neighbor (i.e., ) in , and thus itself belongs to .

Lemma 3.17.

The algorithm has a polynomial-time implementation.

Proof 3.18.

Since is chordal, each minimal separator of is a clique. Since is a shortest path, the size of a clique in is at most . Therefore, every minimal separator of contained in has size at most . Furthermore, every size- minimal separator is an edge of . This observation gives us the following implementation of the algorithm that clearly runs in polynomial time.

For , let be the set of size- minimal - separators of such that and . It suffices to find a shortest - path such that no element of is a subset of . To forbid the elements of , we just remove the vertices that form the size- separators in . Similarly, to forbid the elements of , we remove the edges corresponding to the size- separators in . Now we find a shortest - path in the resultant graph. If has length , then is a non-separating shortest - path in . Otherwise, does not have such a path.

Theorem 3.19.

There is a polynomial-time algorithm for Shortest Non-Separating Path on chordal graphs, provided that is equal to the shortest path distance between and .

4 Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path

The goal of this section is to establish the fixed-parameter tractability and a conditional lower bound on polynomial kernelizations for Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path.

4.1 Fixed-parameter tractability

Theorem 4.1.

Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path can be solved in time , where is the matrix multiplication exponent and is the number of vertices of the input graph .

To prove this theorem, we give a dynamic programming algorithm with the aid of representative families of cographic matroids. Let be an instance of Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path. For and , we define as the family of all sets of edges satisfying the following two conditions: (1) is the set of edges of an - path of length and (2) is connected. An edge set is legitimate if forms a path and is connected. For a family of edge sets and an edge , we define and as the subfamily of consisting of all legitimate . The following simple recurrence correctly computes .

| and | (1) | ||||

| and | (2) | ||||

| . | (3) |

A straightforward induction proves that if and only if has a non-disconnecting - path of length exactly and hence it suffices to check whether for . However, the running time to evaluate this recurrence is . To reduce the running time of this algorithm, we apply Theorem 2.2 to each . Now, instead of (3), we define

| (3’) |

where is a -representative family of for the cographic matroid defined on . In the following, we abuse the notation of to denote the families of legitimate sets that are computed by the recurrence composed of (1), (2), and (3’).

Lemma 4.2.

Proof 4.3.

It suffices to show that if has a non-disconnecting - path of length . Let be a non-disconnecting path in . For , we let . In the following, we prove, by induction on , a slightly stronger claim that there is a legitimate set such that forms a non-disconnecting - path in for all . As and itself is a non-disconnecting path, we are done for . Suppose that . By the induction hypothesis, there is a legitimate such that forms a non-disconnecting - path in . Let . Since is legitimate, is also legitimate, implying that is nonempty. Let be -representative for and let . As , , and , contains an edge set with and , implying that there is such that forms a non-disconnecting - path in . Thus, the lemma follows.

Lemma 4.4.

The recurrence can be evaluated in time , where is the exponent of the matrix multiplication.

Proof 4.5.

By Theorem 2.2, contains at most sets for and and can be computed in time by dynamic programming.

Thus, Theorem 4.1 follows.

4.2 Kernel lower bound

It is well known that a parameterized problem is fixed-parameter tractable if and only if it admits a kernelization (see [6], for example). By Theorem 4.1, Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path admits a kernelization. A natural step next to this is to explore the existence of polynomial kernelizations for Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path. However, the following theorem conditionally rules out the possibility of polynomial kernelization. To prove this, we first show the following lemma.

Lemma 4.6.

Let be a connected graph. Suppose that has a cut vertex . Let be a component in and let . Then, is connected if and only if is connected.

Proof 4.7.

If is connected, then all the vertices in are reachable from in without passing through any vertex in . Thus, such vertices are reachable from in . Conversely, suppose is connected. Then, every vertex in is reachable from in . Moreover, as does not contain any edge outside , every other vertex is reachable from in as well.

Theorem 4.8.

Unless coNP NPpoly, Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path does not admit a polynomial kernelization (with respect to parameter ).

Proof 4.9.

We give an OR-composition for Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path. Let be instances of Shortest Non-Disconnecting Path. We assume that for , is not a cut vertex in . To justify this assumption, suppose that is a cut vertex in . Let be the component in that contains . By Lemma 4.6, for any - path, it is non-disconnecting in if and only if so is in . Thus, by replacing with , we can assume that is not a cut vertex in .

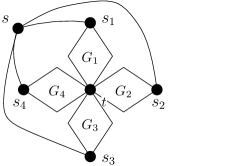

From the disjoint union of , we construct a single instance as follows. We first add a vertex and an edge between and for each . Then, we identify all ’s into a single vertex . See Figure 2 for an illustration.

In the following, we may not distinguish from . Now, we claim that is a yes-instance if and only if is a yes-instance for some .

Consider an arbitrary - path in . Observe that all edges in the path except for that incident to are contained in a single subgraph for some as separates from for . Moreover, the path forms , meaning that the subpath is an - path in . This conversion is reversible: for any - path in , the path obtained from by attaching adjacent to is an - path in . Thus, it suffices to show that for , is a cut of if and only if is a cut of . Since is a cut vertex in , by Lemma 4.6, the claim holds.

References

- [1] Stefan Arnborg, Jens Lagergren, and Detlef Seese. Easy problems for tree-decomposable graphs. J. Algorithms, 12(2):308–340, 1991. doi:10.1016/0196-6774(91)90006-K.

- [2] Hans L. Bodlaender. A linear-time algorithm for finding tree-decompositions of small treewidth. SIAM J. Comput., 25(6):1305–1317, 1996. doi:10.1137/S0097539793251219.

- [3] Hans L. Bodlaender, Rodney G. Downey, Michael R. Fellows, and Danny Hermelin. On problems without polynomial kernels. J. Comput. Syst. Sci., 75(8):423–434, 2009. doi:10.1016/j.jcss.2009.04.001.

- [4] Guantao Chen, Ronald J. Gould, and Xingxing Yu. Graph connectivity after path removal. Comb., 23(2):185–203, 2003. doi:10.1007/s003-0018-z.

- [5] Bruno Courcelle. The Monadic Second-Order Logic of Graphs. I. Recognizable Sets of Finite Graphs. Inf. Comput., 85(1):12–75, 1990.

- [6] Marek Cygan, Fedor V. Fomin, Lukasz Kowalik, Daniel Lokshtanov, Daniel Marx, Marcin Pilipczuk, Michal Pilipczuk, and Saket Saurabh. Parameterized Algorithms. Springer Publishing Company, Incorporated, 1st edition, 2015.

- [7] Erik D. Demaine and Mohammad Taghi Hajiaghayi. Diameter and treewidth in minor-closed graph families, revisited. Algorithmica, 40(3):211–215, 2004. doi:10.1007/s00453-004-1106-1.

- [8] G. A. Dirac. On rigid circuit graphs. Abhandlungen aus dem Mathematischen Seminar der Universität Hamburg, 25:71–76, 1961.

- [9] David Eppstein. Diameter and treewidth in minor-closed graph families. Algorithmica, 27(3):275–291, 2000. doi:10.1007/s004530010020.

- [10] Michael R. Fellows, Danny Hermelin, Frances A. Rosamond, and Stéphane Vialette. On the parameterized complexity of multiple-interval graph problems. Theor. Comput. Sci., 410(1):53–61, 2009. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2008.09.065.

- [11] Fedor V. Fomin, Daniel Lokshtanov, Fahad Panolan, and Saket Saurabh. Efficient computation of representative families with applications in parameterized and exact algorithms. J. ACM, 63(4):29:1–29:60, 2016.

- [12] Martin Grohe and Stephan Kreutzer. Methods for algorithmic meta theorems. In AMS-ASL Joint Special Session, volume 558 of Contemporary Mathematics, pages 181–206. American Mathematical Society, 2009.

- [13] Martin Grohe, Stephan Kreutzer, and Sebastian Siebertz. Deciding first-order properties of nowhere dense graphs. J. ACM, 64(3):17:1–17:32, 2017. doi:10.1145/3051095.

- [14] Alon Itai, Christos H. Papadimitriou, and Jayme Luiz Szwarcfiter. Hamilton paths in grid graphs. SIAM J. Comput., 11(4):676–686, 1982. doi:10.1137/0211056.

- [15] Ken-ichi Kawarabayashi, Orlando Lee, Bruce A. Reed, and Paul Wollan. A weaker version of Lovász’ path removal conjecture. J. Comb. Theory, Ser. B, 98(5):972–979, 2008. doi:10.1016/j.jctb.2007.11.003.

- [16] Matthias Kriesell. Induced paths in 5-connected graphs. J. Graph Theory, 36(1):52–58, 2001. doi:10.1002/1097-0118(200101)36:1<52::AID-JGT5>3.0.CO;2-N.

- [17] Daniel Lokshtanov, Pranabendu Misra, Fahad Panolan, and Saket Saurabh. Deterministic truncation of linear matroids. ACM Trans. Algorithms, 14(2):14:1–14:20, 2018.

- [18] Xiao Mao. Shortest non-separating st-path on chordal graphs. CoRR, abs/2101.03519, 2021. arXiv:2101.03519.

- [19] Haiko Müller. Hamiltonian circuits in chordal bipartite graphs. Discret. Math., 156(1-3):291–298, 1996.

- [20] James G. Oxley. Matroid Theory (Oxford Graduate Texts in Mathematics). Oxford University Press, Inc., USA, 2006.

- [21] Neil Robertson and Paul D. Seymour. Graph minors. III. planar tree-width. J. Comb. Theory, Ser. B, 36(1):49–64, 1984. doi:10.1016/0095-8956(84)90013-3.

- [22] William T. Tutte. How to draw a graph. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, s3-13(1):743–767, 1963. doi:https://doi.org/10.1112/plms/s3-13.1.743.

- [23] Bang Ye Wu and Hung-Chou Chen. The approximability of the minimum border problem. In The 26th Workshop on Combinatorial Mathematics and Computation Theory, 2009.