Evidence for Corotation Origin of Super Metal-Rich Stars in LAMOST-Gaia: Multiple Ridges with a Similar Slope in versus Plane

Abstract

Super metal-rich (SMR) stars in the solar neighborhood are thought to be born in the inner disk and came to present location by radial migration, which is most intense at the co-rotation resonance (CR) of the Galactic bar. In this work, we show evidence for the CR origin of SMR stars in LAMOST-Gaia by detecting six ridges and undulations in the versus space coded by median , following a similar slope of . The slope is predicted by Monario et al.’s model for CR of a large and slow Galactic bar. For the first time, we show the variation of angular momentum with azimuths from to for two outer and broad undulations with negative around following this slope. The wave-like pattern with large amplitude outside CR and a wide peak of the second undulations indicate that minor merger of the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy with the disk might play a role besides the significant impact of CR of the Galactic bar.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the release of the Gaia data, rich structures in the phase-space distribution have been revealed. For instance, multiple ridges displayed in velocity space were found by Gaia Collaboration et al. (2018) and Ramos et al. (2018). Fragkoudi et al. (2019) also reported the ridge of the Hercules moving group, and many features, so-called ”horn” and ”hat”, in the versus coded by mean velocity. The origins of these rich structures is a debate topic with the Hercules moving group as a typical case. It has been suggested that the Hercules moving group, first reported in Dehnen (1999), was formed outside of the bar’s outer Lindblad resonance (OLR) based on a faster bar (Monari et al., 2016). However, Pérez-Villegas et al. (2017) favored for the scenario that orbits trapped at the co-rotation resonance (CR) of a slow bar could produce the Hercules moving group in local velocity space. Based on the Galactic model of Pérez-Villegas et al. (2017), Monari et al. (2019b) proposed that no fewer than six ridges in local action space that can be related to resonances of this slow bar, which induces a wave-like pattern with wavenumber of excitation. However, Friske & Schönrich (2019) explained the ridges in the average Galactocentric radial velocity as a function of angular momentum and azimuth as a wavenumber pattern caused by spiral arms.

Most of the observed structures in the phase-space distribution can be explained by different combinations of non-axisymmetric perturbations, making their modeling degenerate (Hunt et al., 2019). Meanwhile, the relative contribution of the CR and OLR resonances (e.g. for the Hercules moving group) is different between the slow and fast rotation speed of the Galactic bar. The combination of different resonances due to various perturbations make it difficult to discover their origins. Following the ridges as a function of azimuth provides a promising way to disentangle the effect of different resonances. In this respect, Monari et al. (2019a) shows that the Hercules angular momentum changes significantly with azimuth as expected for the CR resonance of a dynamically old large bar. They proposed that such a variation would not happen close to the OLR of a faster bar at least for 2 Gyr after its formation.

In this letter, we investigate the variation of angular momentum () with Galactic azimuth () coded by using SMR stars in the LAMOST-Gaia survey as tracers. Since SMR stars in the solar neighborhood are thought to originate from the inner disk (Kordopatis et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2019, 2003), features related to the CR resonance of the Galactic bar should be easily identified in this special population.

2 Data

SMR stars with and spectral signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) larger than 10 are selected from LAMOST DR7 (Zhao et al., 2006, 2012; Cui et al., 2012; Deng et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2015), which provide radial velocity and updated stellar parameters based on methods in Luo et al. (2015). Then we cross-match this sample with Gaia EDR3 (Gaia Collaboration et al., 2021) to obtain proper motions, and limit stars with errors in proper motions less than 0.05 , and the renormalized unit weight error of (Lindegren et al., 2018). Bayesian distances are from the StarHorse code (Anders et al., 2019) using Gaia EDR3 and stars with relative error less than 10% are adopted. The radial velocity are based on the LAMOST survey, and stars with errors in radial velocity larger than 10 are excluded from the sample.

Galactocentric positions, spatial velocity and orbital parameters (apocentric/pericentric distances, and ) are calculated based on the publicly available code Galpot with the default potential (MilkyWayPotential) provided by McMillan (2017). Note that are calculated with the definition of Equation (3.72) as presented in Binney & Tremaine (2008), while Monari et al. (2019a) adopted an approximate value of . We use the cylindrical coordinate (, , ) with the Sun’s distance from the Galactic centre kpc, the solar peculiar velocity of ( (11.1, 12.24, 7.25) (Schönrich et al., 2010) and the circular speed of (McMillan, 2011). The sample have 214,199 star stars with velocities between and , and the velocity dispersions of (36.1,23.1, 17.3) in (, , ). Their Galactic locations are of kpc, and kpc with peaks at kpc and kpc, respectively.

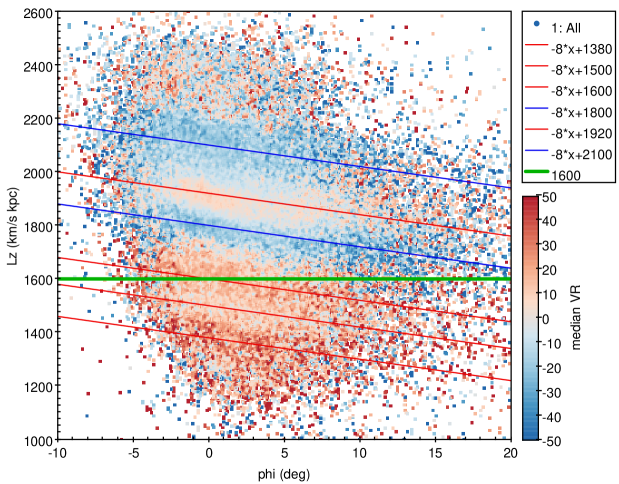

3 The versus plane

Figure 1 shows the versus space coded by median for SMR stars. There are six ridges and undulations, generally following a similar slope of , which is predicted for stars with orbits trapped at CR in the Galactic model of Monari et al. (2019b). The red ridge with positive median following the red line of corresponds to the Hercules moving group in Monari et al. (2019a), and for comparison we plot the green line, which has a zero slope with at , as expected for the OLR in the bar model. Note that the range of mean in Monari et al. (2019a) (their Fig. 2) is of , while the coverage of in median is adopted in our Fig. 1. The uncertainties of the median for these features are of 0.5-1.0 km/s.

Except for the Hercules moving group, two ridges (with intercepts of and kpc) and three undulations (with intercepts of , and kpc) are clearly shown. The similar slope in the versus plane for the six ridges and undulations indicates that the bar’s resonance is not limited within the location of Hercules moving group (), but has significant effect in the solar neighborhood ( ).

Meanwhile, positive median are found for the inner region of , above which median are negative except for a narrow ridge of with median in the order of . This transition may indicates that minor merge event might start to take effect, which significantly increase the variation amplitude and make the undulations wider. Since the slope of persists, we expect that the role of the CR is still significant in the outer region of for SMR stars. Interestingly, Gaia Collaboration et al. (2022) found a somewhat similar velocity distribution with a lower velocity variation (see their Fig. 16), but a change in the sign of velocity (as a function of Galactocentric angle) at a radius of 10 kpc, in phase with the bar angle, is not seen in our SMR sample because only a small fraction of SMR stars in our sample could reach to 10 kpc.

Although the wave-like pattern between the ridges and undulations are found for both the inner and outer regions but the amplitudes and the widths are different. The two blue undulations in the outer region have (negative) median of , while the two ridges in the inner disk have (positive) median around . The width of the outest undulation at is largest, spanning a range of 2.5 kpc from to kpc in term of guiding radius , and the median is the most negative, which indicates extra mechanisms, such as the minor merge of the Sgr dwarf galaxy, may play an important contribution to this undulation.

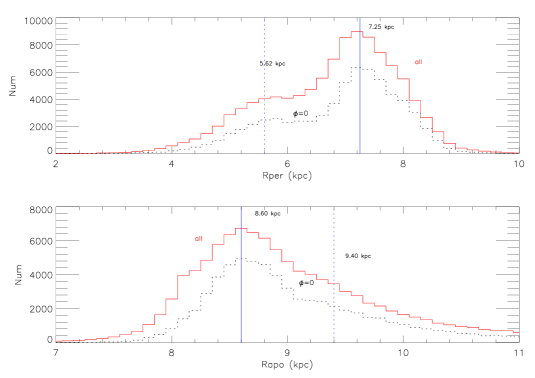

4 The distributions of pericentre and apocentre distances

In order to know how far these SMR stars can reach in the Galactic inner and outer disks, Fig. 2 shows the distribution of pericentre and apocentrc distances for all stars (red solid lines) and stars aligned with the Sun and the Galactic centre (black dash lines). Then we fit the distributions with two gaussian functions for stars at the solar azimuth () and obtain two peaks for pericentre and apocentre distances respectively. The main peak of pericentre distance is at 7.25 kpc and a second peak at 5.62 kpc, while the histogram of apocentre distance shows a main peak at 8.6 kpc and the second peak at 9.4 kpc. It is found that 79% SMR stars excurse within 4 kpc around the location of the Sun at 8.2 kpc. The second peak of pericentre distance at 5.6 kpc is interesting because it is close to the CR position at 6 kpc in Pérez-Villegas et al. (2017) and very close to 5.5 kpc in Bovy et al. (2019) for a slow bar. There are 36% SMR stars with pericentre distance less than 6.5 kpc, and they are significantly affected by the CR of the Galactic bar. Finally, the apocentre distribution has a second peak at 9.4 kpc, which is within the the bar’s OLR at about 10.5 kpc according to Pérez-Villegas et al. (2017).

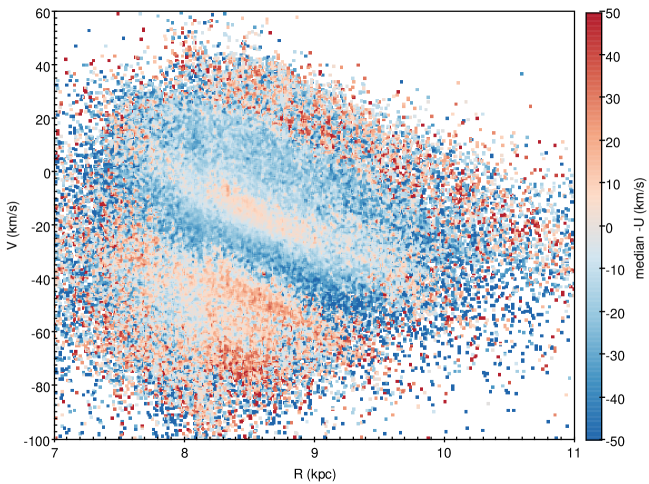

5 Comparison with the Galactic bar model

Based on a realistic model for a slowly rotating large Galactic bar with pattern speed of , Monari et al. (2019b) show no fewer than six ridges in local action space that can be related to resonances with the bar. It is interesting that SMR stars in the present sample do show six ridges and undulations in the versus plane. For direct compariosn, we adopt the Galactic coordinate frame for stellar velocity (U,V,W) and show the diagram coded by median in Fig. 3, which matches their Fig. 6 quite well. Specifically, the ridge at of corresponds to CR (their green line) feature and the undulation at fits the OLR (their red line) feature. The two ridges (at and ) are associated with the 6:1 (pink) and 3:1 (purple) resonances, and one undulation at is related to the 4:1 (blue) resonance.

Note that the two ridges at and in the present work are the same as the strong positive features near and observed in the solar neighborhood by Chiba & Schönrich (2021) based on Gaia DR2 as a result of the bar’s resonance. They also suggested a slow bar with the current pattern speed of , and placed the corotation radius at kpc. Moreover, Chiba et al. (2021) introduced a decelerating bar model, which can reproduce with its corotation resonance the offset and strength of the Hercules stream in the local versus plane and the double-peaked structure of mean in the plane due to the accumulation of orbits near the boundary of the resonance. Further work on the comparison of the model’s result with observation is desire.

In sum, the multiple ridges and undulations found for SMR stars in Fig. 1 can be explained by the bar resonances in the model of Monari et al. (2019b). Their similar slope indicates that these features (even in the OLR region) are affected by the CR of the slow and long bar. But the strong modulations from ridges to undulations and very wide range in the last undulation beyond the CR region suggest that minor merger may also play an role in the Galactic disk.

Finally, we investigate chemical signatures of the six ridges and undulations based on abundances in Li et al. (2022), and there are 42,109 SMR stars with [Mg/Fe] ratios available. There is no difference in [Mg/Fe] among ridges and undulations. Both have a peak at dex, typical for the old bar. Based on the LAMOST middle resolution survey, Zhang et al. (2021) also suggested that SMR stars have slightly enhanced dex. Note that stars from the Sgr dwarf galaxy itself usually have low at , and there is no star with solar metallicity as shown in Fig. 9 of Zhao & Chen (2021). Therefore, these SMR stars in the present work are not from the Sgr dwarf galaxy itself, but the minor merge event of the Sgr dwarf galaxy with the Galactic disk could induce strong modulations of from ridges to undulations, and make the undulation at becomes wider.

6 Conclusions

We have detected, for the first time, six ridges and undulations following a single slope in the versus plane coded by median from a specific population of SMR stars based on LAMOST DR7 and Gaia EDR3. Specifically, the variation of radial velocity with angular momentum and azimuth for the six ridges and undulations is seen with a similar slope of , which is predicted for stars with orbits trapped at the CR of a slow bar in the model of Monari et al. (2019b). The median shifts from positive to negative values at kpc (for , ). This transition may indicate the role of minor merge starts to take effect together with the contribution from the CR of the bar. The most outer undulation around kpc (for , ) has a wide feature (three times larger than ridges), which is probably also related to the minor merge event of the Galactic disk with Sgr dwarf galaxy, but this remains an open question for further study in the future. Moreover, since the major merge event by the Gaia-Sausage-Enceladus galaxy bring its metal-rich component (Zhao & Chen, 2021), and the accreted halo stars with special chemistry (Xing et al., 2019), into the solar neighborhood, it is interesting to probe how major merge events take effect on the existence of these ridges and undulations. Finally, many moving groups exist in the solar neighborhood (Zhao et al., 2009), and it is of high interest to probe if they may leave some imprints in the versus plane coded by median as the Hercules moving group.

Guoshoujing Telescope (the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope, LAMOST) is a National Major Scientific Project has been provided by the National Development and Reform Commission. LAMOST is operated and managed by the National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences. This work has made use of data from the European Space Agency (ESA) mission Gaia (https://www.cosmos.esa.int/gaia), processed by the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC, https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/gaia/dpac/consortium). Funding for the DPAC has been provided by national institutions, in particular the institutions participating in the Gaia Multilateral Agreement.

References

- Anders et al. (2019) Anders, F., Khalatyan, A., Chiappini, C., et al. 2019, A&A, 628, A94, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201935765

- Binney & Tremaine (2008) Binney, J., & Tremaine, S. 2008, Galactic Dynamics: Second Edition

- Bovy et al. (2019) Bovy, J., Leung, H. W., Hunt, J. A. S., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 490, 4740, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stz2891

- Chen et al. (2003) Chen, Y. Q., Zhao, G., Nissen, P. E., Bai, G. S., & Qiu, H. M. 2003, ApJ, 591, 925, doi: 10.1086/375292

- Chen et al. (2019) Chen, Y. Q., Zhao, G., Zhao, J. K., et al. 2019, AJ, 158, 249, doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/ab5283

- Chiba et al. (2021) Chiba, R., Friske, J. K. S., & Schönrich, R. 2021, MNRAS, 500, 4710, doi: 10.1093/mnras/staa3585

- Chiba & Schönrich (2021) Chiba, R., & Schönrich, R. 2021, MNRAS, 505, 2412, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stab1094

- Cui et al. (2012) Cui, X.-Q., Zhao, Y.-H., Chu, Y.-Q., et al. 2012, Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 12, 1197, doi: 10.1088/1674-4527/12/9/003

- Dehnen (1999) Dehnen, W. 1999, ApJ, 524, L35, doi: 10.1086/312299

- Deng et al. (2012) Deng, L.-C., Newberg, H. J., Liu, C., et al. 2012, Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 12, 735, doi: 10.1088/1674-4527/12/7/003

- Fragkoudi et al. (2019) Fragkoudi, F., Katz, D., Trick, W., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 488, 3324, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stz1875

- Friske & Schönrich (2019) Friske, J. K. S., & Schönrich, R. 2019, MNRAS, 490, 5414, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stz2951

- Gaia Collaboration et al. (2021) Gaia Collaboration, Brown, A. G. A., Vallenari, A., et al. 2021, A&A, 649, A1, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202039657

- Gaia Collaboration et al. (2022) Gaia Collaboration, Drimmel, R., Romero-Gomez, M., et al. 2022, arXiv e-prints, arXiv:2206.06207. https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.06207

- Gaia Collaboration et al. (2018) Gaia Collaboration, Katz, D., Antoja, T., et al. 2018, A&A, 616, A11. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201832865

- Hunt et al. (2019) Hunt, J. A. S., Bub, M. W., Bovy, J., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 490, 1026, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stz2667

- Kordopatis et al. (2015) Kordopatis, G., Wyse, R. F. G., Gilmore, G., et al. 2015, A&A, 582, A122, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201526258

- Li et al. (2022) Li, Z., Zhao, G., Chen, Y., Liang, X., & Zhao, J. 2022, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stac1959

- Lindegren et al. (2018) Lindegren, L., Hernández, J., Bombrun, A., et al. 2018, A&A, 616, A2, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201832727

- Liu et al. (2015) Liu, X.-W., Zhao, G., & Hou, J.-L. 2015, Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 15, 1089, doi: 10.1088/1674-4527/15/8/001

- Luo et al. (2015) Luo, A. L., Zhao, Y.-H., Zhao, G., et al. 2015, Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 15, 1095, doi: 10.1088/1674-4527/15/8/002

- McMillan (2011) McMillan, P. J. 2011, MNRAS, 414, 2446, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18564.x

- McMillan (2017) —. 2017, MNRAS, 465, 76, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw2759

- Monari et al. (2016) Monari, G., Famaey, B., & Siebert, A. 2016, MNRAS, 457, 2569, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw171

- Monari et al. (2019a) Monari, G., Famaey, B., Siebert, A., et al. 2019a, A&A, 632, A107, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201936455

- Monari et al. (2019b) Monari, G., Famaey, B., Siebert, A., Wegg, C., & Gerhard, O. 2019b, A&A, 626, A41, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201834820

- Pérez-Villegas et al. (2017) Pérez-Villegas, A., Portail, M., Wegg, C., & Gerhard, O. 2017, ApJ, 840, L2, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aa6c26

- Ramos et al. (2018) Ramos, P., Antoja, T., & Figueras, F. 2018, A&A, 619, A72, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201833494

- Schönrich et al. (2010) Schönrich, R., Binney, J., & Dehnen, W. 2010, MNRAS, 403, 1829, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.16253.x

- Xing et al. (2019) Xing, Q.-F., Zhao, G., Aoki, W., et al. 2019, Nature Astronomy, 3, 631, doi: 10.1038/s41550-019-0764-5

- Zhang et al. (2021) Zhang, H.-P., Chen, Y.-Q., Zhao, G., et al. 2021, Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 21, 153, doi: 10.1088/1674-4527/21/6/153

- Zhao & Chen (2021) Zhao, G., & Chen, Y. 2021, Science China Physics, Mechanics, and Astronomy, 64, 239562, doi: 10.1007/s11433-020-1645-5

- Zhao et al. (2006) Zhao, G., Chen, Y.-Q., Shi, J.-R., et al. 2006, Chinese J. Astron. Astrophys., 6, 265, doi: 10.1088/1009-9271/6/3/01

- Zhao et al. (2012) Zhao, G., Zhao, Y.-H., Chu, Y.-Q., Jing, Y.-P., & Deng, L.-C. 2012, Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 12, 723, doi: 10.1088/1674-4527/12/7/002

- Zhao et al. (2009) Zhao, J., Zhao, G., & Chen, Y. 2009, ApJ, 692, L113, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/692/2/L113