Combining Squeezing and Transition Sensitivity Resources for Quantum Metrology by Asymmetric Non-Linear Rabi model

Abstract

Squeezing and transition criticality are two main sensitivity resources for quantum metrology (QM), combination of them may yield an upgraded metrology protocol for higher upper bound of measurement precision (MP). We show that such a combination is feasible in light-matter interactions by a realizable asymmetric non-linear quantum Rabi model (QRM). Indeed, the non-linear coupling possesses a squeezing resource for diverging MP while the non-monotonous degeneracy lifting by the asymmetries induces an additional tunable transition which further enhances the MP by several orders, as demonstrated by the quantum Fisher information. Moreover, the protocol is immune from the problem of diverging preparation time of probe state that may hinder the conventional linear QRM in application of QM. This work establishes a paradigmatic case of combining different sensitivity resources to manipulate QM and maximize MP.

pacs:

Introduction.–The past two decades have witnessed both theoretical Braak2011 ; Solano2011 ; Boite2020 ; Liu2021AQT and experimental progresses Diaz2019RevModPhy ; Kockum2019NRP in light-matter interactionsEckle-Book-Models ; JC-Larson2021 , opening a frontier field for explorations of exotic quantum states and developments of quantum technologies. In particular, light-matter interactions manifest finite-component quantum phase transitions (QPTs) Liu2021AQT ; Ashhab2013 ; Ying2015 ; Hwang2015PRL ; Ying2020-nonlinear-bias ; Ying-2021-AQT ; LiuM2017PRL ; Hwang2016PRL ; Irish2017 ; Ying-gapped-top ; Ying-Stark-top ; Ying-Spin-Winding ; Ying-2018-arxiv ; Ying-JC-winding ; Ying-Topo-JC-nonHermitian ; Ying-Topo-JC-nonHermitian-Fisher ; Ying-gC-by-QFI-2024 ; Grimaudo2022q2QPT ; Grimaudo2023-Entropy ; Zhu2024PRL which have great application potential for critical quantum metrology (QM) with high measurement precision (MP) Garbe2020 ; Garbe2021-Metrology ; Ilias2022-Metrology ; Chu2021-Metrology ; Ying2022-Metrology ; Montenegro2021-Metrology ; Hotter2024-Metrology .

Indeed, amidst the emerging phenomenology LiPengBo-Magnon-PRL-2024 ; Qin-ExpLightMatter-2018 ; Li2020conical ; Batchelor2015 ; ChenQH2012 ; PengJ2021PRL ; PengJie2019 ; PRX-Xie-Anistropy ; Irish-class-quan-corresp ; Irish2014 ; JC-Larson2021 ; WangZJ2020PRL ; Lu-2018-1 ; Ashhab2013 ; Ying2015 ; Hwang2015PRL ; Ying2020-nonlinear-bias ; Ying-2021-AQT ; LiuM2017PRL ; Hwang2016PRL ; Irish2017 ; Ying-gapped-top ; Ying-Stark-top ; Ying-Spin-Winding ; Ying-2018-arxiv ; Ying-JC-winding ; Ying-Topo-JC-nonHermitian ; Ying-Topo-JC-nonHermitian-Fisher ; Ying-gC-by-QFI-2024 ; Grimaudo2022q2QPT ; Grimaudo2023-Entropy ; Zhu2024PRL ; Cong2022Peter ; Eckle-2017JPA ; Ma2020Nonlinear ; Yan2023-AQT ; Lyu24-Multicritical ; Zheng2017 ; ZhengHang2017 ; Padilla2022 ; Yimin2018 ; Wu24-RabiTransition-Exp ; Gao2022Rabi-dimer ; Gao2022Rabi-aniso ; Simone2018 ; FelicettiPRL2020 ; Alushi2023PRX ; LiuGang2023 ; YPWang2023QuanContrMag ; AiQ2023 ; KuangLM2024AQT ; DiBello2024 ; Zhu-PRL-2020 ; Felicetti2015-TwoPhotonProcess ; e-collpase-Garbe-2017 ; Rico2020 ; e-collpase-Duan-2016 ; CongLei2019 ; Felicetti2018-mixed-TPP-SPP ; Boite2016-Photon-Blockade ; Ridolfo2012-Photon-Blockade ; Casanova2018npj ; Braak2019Symmetry finite-component QPTs exhibit exotic properties of criticality and universality Ashhab2013 ; Ying2015 ; Hwang2015PRL ; LiuM2017PRL ; Hwang2016PRL ; Irish2017 ; Ying-2021-AQT ; Ying-Stark-top , multi-criticality Ying2020-nonlinear-bias ; Ying-2021-AQT ; Ying-gapped-top ; Ying-Stark-top ; Ying-2018-arxiv ; Ying-JC-winding ; Zhu2024PRL ; Lyu24-Multicritical ; Wu24-RabiTransition-Exp , compromise of universality and diversity Ying-2021-AQT ; Ying-Stark-top , topological phase transitions with Ying-2021-AQT ; Ying-gapped-top ; Ying-Stark-top and without Ying-gapped-top ; Ying-Stark-top ; Ying-Spin-Winding ; Ying-JC-winding gap closing, spin knot states Ying-Spin-Winding , coexistence of Landau-class and topological-class transitions Ying-2021-AQT ; Ying-Stark-top ; Ying-JC-winding ; Ying-Topo-JC-nonHermitian-Fisher , robust topological feature against non-Hermiticity Ying-Topo-JC-nonHermitian and universal criticality of exceptional points Ying-Topo-JC-nonHermitian-Fisher . In reality, in the contemporary era of ultra-strong coupling Ciuti2005EarlyUSC ; Aji2009EarlyUSC ; Diaz2019RevModPhy ; Kockum2019NRP ; Wallraff2004 ; Gunter2009 ; Niemczyk2010 ; Peropadre2010 ; FornDiaz2017 ; Forn-Diaz2010 ; Scalari2012 ; Xiang2013 ; Yoshihara2017NatPhys ; Kockum2017 ; Ulstrong-JC-2 ; Ulstrong-JC-3-Adam-2019 ; PRX-Xie-Anistropy and deep-strong coupling Yoshihara2017NatPhys ; Bayer2017DeepStrong ; Ulstrong-JC-1 ; DeepStrong-JC-Huang-2024 finite-component QPTs are experimentally accessible Yimin2018 ; Wu24-RabiTransition-Exp ; Chen-2021-NC .

A most promising application of the finite-component QPTs lies in QM Garbe2020 ; Garbe2021-Metrology ; Ilias2022-Metrology ; Chu2021-Metrology ; Ying2022-Metrology ; Montenegro2021-Metrology ; Hotter2024-Metrology , with the advantage of high controllability and free of difficulty of reaching the equilibrium in thermodynamical systems. Without doubt the main goal in QM is to raise MP as much as possible. Generally speaking there are various resources for MP Degen2017-QuantSensing , including squeezing Maccone2020Squeezing ; Lawrie2019Squeezing ; Gietka2023PRL-Squeezing ; Gietka2023PRL2-Squeezing , entanglement Pezze2018entangelment and transition criticality Garbe2020 ; Garbe2021-Metrology ; Ilias2022-Metrology ; Chu2021-Metrology ; Ying2022-Metrology ; Montenegro2021-Metrology ; Hotter2024-Metrology . These resources individually can achieves high MP. One may wonder about the possibility of combining different resources. Another issue concerned in QM is the reduction of preparation time of the probe state (PTPS) Garbe2020 ; Ying2022-Metrology ; Gietka2022-ProbeTime . In fact the PTPS in the linear quantum Rabi model (QRM) is diverging in the low-frequency limit where the QPT occurs Garbe2020 ; Ying2022-Metrology , which may hinder the application for QM in practice. Protocols with higher MP but finite PTPS are more favorable and desirable.

In the present work, rather than in the conventional low-frequency limit we reveal a tunable QPT in the low-tunneling limit. We show that the resource combination for QM can be realized in light-matter interactions by an asymmetric non-linear quantum Rabi model. As demonstrated by the quantum Fisher information (QFI), the non-linear coupling possesses a squeezing resource for diverging MP while the asymmetry competition introduces the additional QPT which raises the MP more by several orders. Favorably, the protocol has finite PTPS due to finite frequency and gap.

Model and asymmetries.–We consider a non-linear QRM

| (1) |

which describes a quadratic coupling between a bosonic mode with frequency , created (annihilated) by (, and a qubit represented by the Pauli matrices . As a comparison the linear QRM rabi1936 ; Rabi-Braak ; Eckle-Book-Models has a coupling in form of . Here the quadratic coupling can be rewritten asYing-2018-arxiv ; Ying2020-nonlinear-bias

| (2) |

with , while the case is called the two-photon QRM Felicetti2018-mixed-TPP-SPP ; Felicetti2015-TwoPhotonProcess ; e-collpase-Garbe-2017 ; Rico2020 ; e-collpase-Duan-2016 ; CongLei2019 and is a Stark-like term Eckle-2017JPA . Although the case is more symmetric with symmetry , the full quadratic form with in (1) is more original in circuit systems Felicetti2018-mixed-TPP-SPP . While the bias is usually responsible for asymmetry Braak2011 ; HiddenSymLi2021 ; HiddenSymBustos2021 ; HiddenSymMangazeev2021 ; Ying-2018-arxiv ; Ying2020-nonlinear-bias , the term introduces a new asymmetry origin to break the symmetry. Another symmetry Ying-2021-AQT ; Ying-JC-winding takes the place in , however it lifts the spin degeneracy imposed by . Such a symmetry variation releases a non-monotonous degeneracy lifting and brings about a first-order-like transition which provides the transition sensitivity resource in addition to the squeezing resource for the combined QM, as we shall address in this work.

For the convenience of further analysis, by transformation with position and momentum , we can rewrite as Irish2014 ; Ying2015 ; Ying-2018-arxiv ; Ying2020-nonlinear-bias where labels the spin in direction. Here is the effective singe-particle Hamiltonian, in the spin-dependent harmonic potential

| (3) |

with effective mass , renormalized frequency and single-particle energy , where

| (4) |

Here , before the spectral collapse point Ying-2018-arxiv ; Ying2020-nonlinear-bias ; Felicetti2018-mixed-TPP-SPP ; Felicetti2015-TwoPhotonProcess ; e-collpase-Garbe-2017 ; Rico2020 ; e-collpase-Duan-2016 ; CongLei2019 . In such a formalism the term plays the role of spin flipping in the spin space or tunneling in the position space Irish2014 ; Ying2015 ; flux-qubit-Mooij-1999 . Hereafter we consider the ground state which has .

Diverging QFI in case.–In QM the MP of experimental estimation on a parameter is bounded by Cramer-Rao-bound , where is the QFI defined as Cramer-Rao-bound ; Taddei2013FisherInfo ; RamsPRX2018

| (5) |

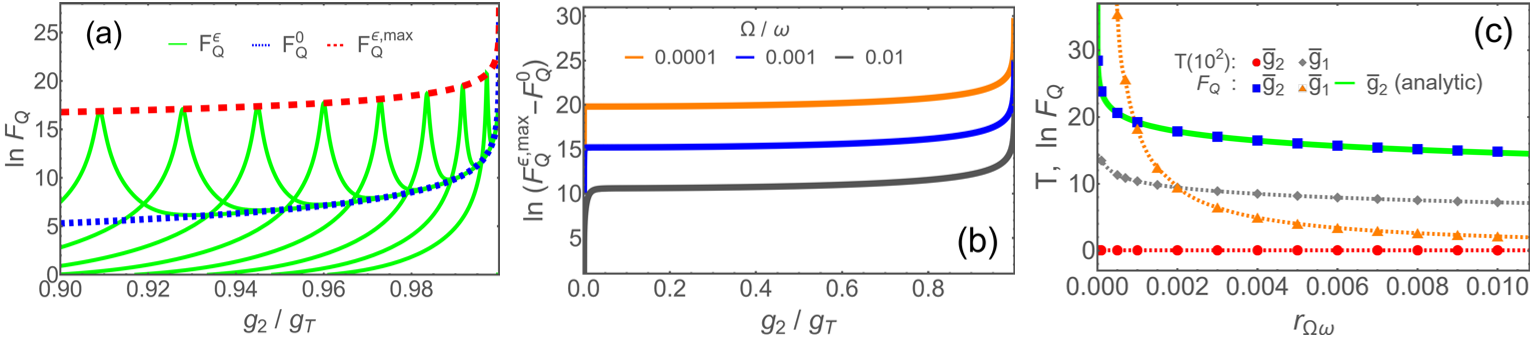

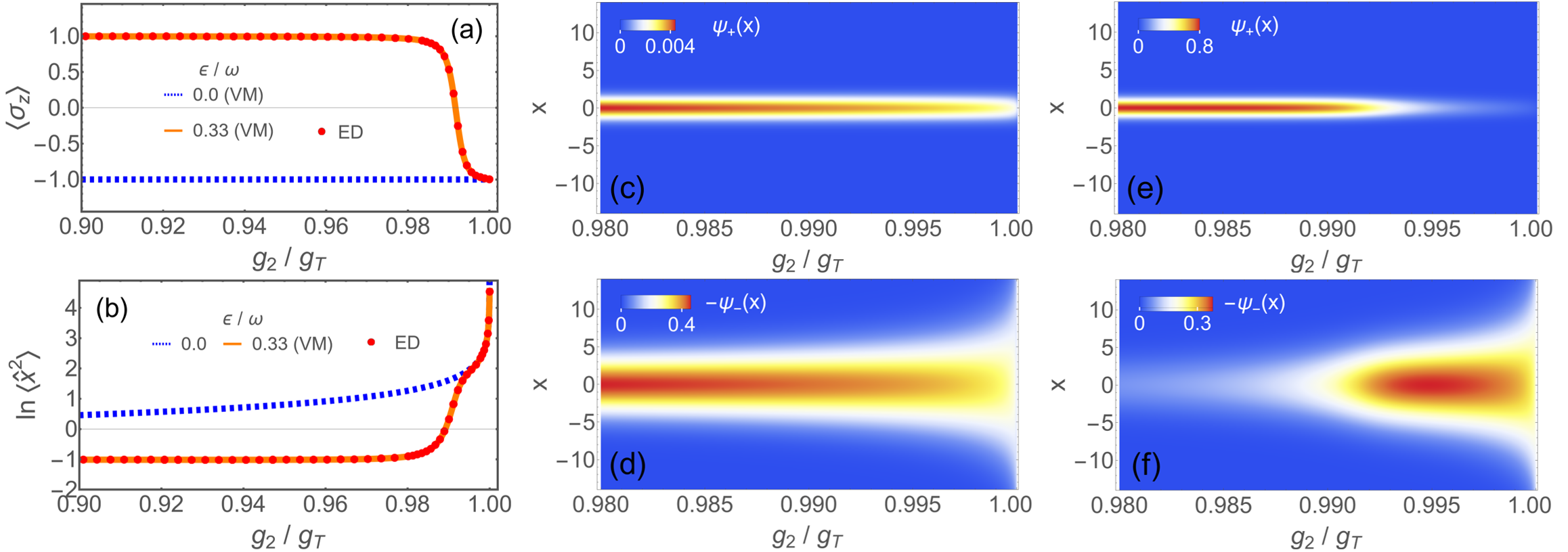

for a pure states . Here ′ denotes the derivative with respect to the parameter . A higher QFI would mean a higher MP for QM. In the absence of the bias, the QFI for the parameter manifests a diverging behavior when approaches , as demonstrated by the dotted line in Fig.1(a). Such a diverging QFI comes from the squeezing effect driven by the frequency renormalization . Indeed, as shown in Fig.2(c) and 2(d) the wave function is narrowing (widening) in the spin-up (spin-down) component, corresponding to an amplitude (phase) squeezing Ref-Squeezing . In particular, such a squeezing effect is divergently strong in as is vanishing in approaching . Note that the single-particle energy in the ground state, , is lower in the spin-down component. Thus has a dominate weight in a low ratio, as indicated by the spin expectation value, , denoted by the dotted line in Fig.2(a). The accelerated squeezing, especially in in the vicinity of , provides sensitivity resource for the diverging QFI.

Upgraded QFI in case.–The QFI can be much enlarged in the presence of the bias. Indeed, as illustrated by Fig.1(a), high peaks (green solid lines) emerge when finite values of bias are introduced. Note that such peak values are higher by several orders than the values in the case (blue dotted line), thus providing a continuously reachable upper bound of QFI values (red dashed line). By tuning to a lower ratio, in finite cases one can gain a larger extra value of the QFI over the already diverging , as shown by Fig.1(b).

Combined squeezing and transition sensitivity resources.–Actually the QFI is also equivalent to the susceptibility of the fidelity whose peak signals a QPT Zhou-FidelityQPT-2008 ; Zanardi-FidelityQPT-2006 ; Gu-FidelityQPT-2010 ; You-FidelityQPT-2007 ; You-FidelityQPT-2015 , as applied to extract the accurate frequency dependence of the second-order-like transition of the linear QRM Ying-gC-by-QFI-2024 . Here for the non-linear QRM the QFI peaks in case also arise from a bias-tuned first-order-like transition, as illustrated by the fast change in (orange solid line) around in Fig.2(a). One can see that the transition indeed adds a boost of property variation (orange solid line) to the original fast changing from the squeezing effect (dotted line) in in Fig.2(b). More essentially in the wave function, the amplitude of decreases quickly while that of grows fast around the transition, as in Figs.2(e) and 2(f), in addition to the wave-packet narrowing and broadening of and . Such a quicker variation in the wave function resulting from both the transition and the squeezing yields a combined sensitivity resource for the enlargements of and upgraded MP.

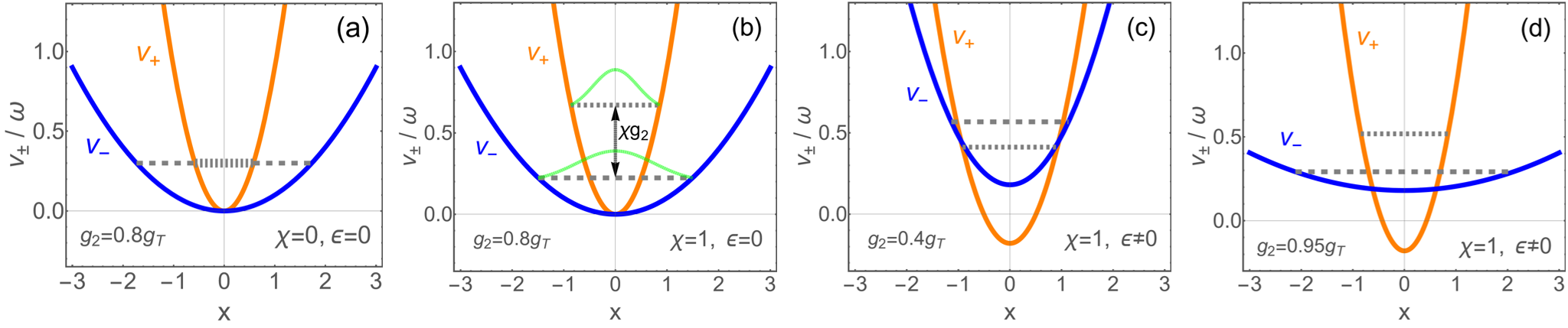

Transition point and optimal bias.–The emerged transition in finite bias can be seen clearly by the formalism in . Firstly we stress that such a coupling-driven transition does not exist in the conventional two-photon QRM ( case) as we have always degenerate single-particle energy in Fig.3(a), due to in such situation, while an added bias only lifts the degeneracy monotonously which cannot bring a transition in coupling variation. In contrast, in case, the degeneracy is already lifted in the absence of bias by the coupling, with , as in Fig.3(b). In the presence of bias, the two energy levels can be reversed in a small , with , as in Fig.3(c), while they can be reversed again in a large , recovering , as in Fig.3(d). The level crossing gives the transition point

| (6) |

at a given bias. Since the transition point has the peak, we can tune the bias, for measurements at a coupling , to the optimal one at which the value reaches the maximum.

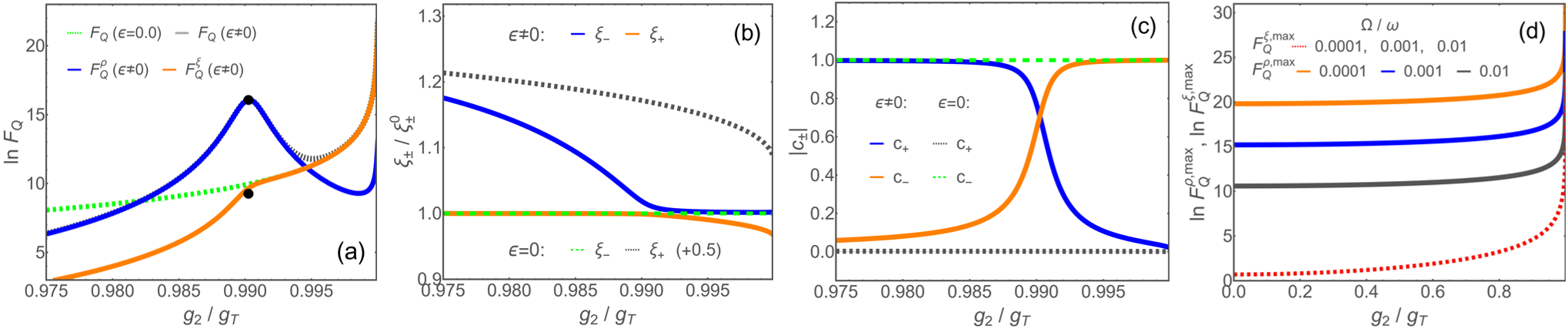

QFI-contribution tracking for two resources.–To have a better view of the contributions of the two sensitivity resources to the QFI, we can assume where is the ground state of harmonic oscillator with frequency renormalization factor as in the variational method of polaron pictureYing2015 . Here and , with and subject to normalization condition . The final is determined by the minimization of the variational energy , where the ground state takes the branch from and , .

Note for a real wave functionYing-gC-by-QFI-2024 , the QFI is simplified to be which finally only contains two parts: where

| (7) |

and . Apparently is the contribution from the squeezing effect, while is the contribution from the wave-packet weight variation in the transition. We find that the mixed term of the two resources, with mixed variation factor , vanishes here as due to the basis normalization . The variation of is illustrated in Fig.4(c), showing a quick change around the transition at the finite bias in contrast to the locally flat behavior at zero bias. The evolution of rescaled by is plotted in Fig.4(b), indicating that the variation of mainly follows the scale of despite of a critical-like behavior before and after for [blue (dark-gray) solid) and [orange (light-gray) solid] respectively. The contributions of [blue (dark-gray) solid] and [orange (light-gray) solid] at the finite bias are tracked in Fig.4(a), we see that maintains basically the same amount of QFI as in case (green dotted) after . There is some discount in regime due to the smaller weight in , which however doesnot affect the upper bound of QFI that is what we need. On the other hand, from Fig.4(a) we see that indeed is responsible for the dramatic increase of the QFI. Since the transition occurs around the degenerate point of the single-particle energy, we can readily obtain in the leading order the two contributions at explicitly as

| (8) | |||||

| (9) |

where and . The analytic results of and agree well with the numerics, as denoted by the black dots in Fig.4(a) [also squares in Fig.1(c)]. We see that one gets a diverging in proximity of universally for small ratios of , while diverging is available overall regime with respect to small ratios of , as shown in Fig.4(d). Around the tunable is larger than as long as , e.g., ( guarantees a larger for ( which actually covers the entire practical regime.

Gap and PTPS.–Another issue concerned in QM is the PTPS, which is inversely proportional to the instantaneous gap as estimated by . The conventional linear QRM has a second-order QPT in the opposite limit Ashhab2013 ; Ying2015 ; Hwang2015PRL ; LiuM2017PRL ; Irish2017 applied for QM Garbe2020 , the PTPS is however diverging Garbe2020 ; Ying2022-Metrology as the exponentially closing gap is overall in order of Ying-2021-AQT ; Ying2022-Metrology . In contrast, for the non-linear model here, the gap has an order of apart from an unclosed minimum gap around and does not overall vanish due to finite and . Such a gap situation guarantees an always finite PTPS. Indeed, as compared in Fig.1(c) with , the PTPS in non-linear case (dots) is only a single digit while it is diverging in linear case (triangles). We have not mentioned that the QFI is also higher by orders, as shown by the squares (non-linear) and diamonds (linear) in Fig.1(c). Thus our non-linear protocol is more favorable in practice than the linear one in applications for QM.

Conclusion.–With the asymmetric non-linear QRM realizable in circuit systems we have explored an upgraded protocol of QM by a combination of squeezing and transition sensitivity resources. The tunable asymmetry-induced transition adds a dramatic increase of QFI over the already-diverging QFI from the squeezing resource, indicating an improvement of MP by orders. In addition, the protocol is immune from the problem of diverging PTPS which exists in the conventional linear QRM in application of QM. We have clarified the mechanism for the improvement and obtained analytic results of the maximum QFI and the optimal bias. Our work establishes a paradigmatic case of combining different sensitivity resources to upgrade QM in light-matter interactions. A broader combination to include entanglement resource by adding more qubits and bosonic modes might be even more advantageous, which can be a further work.

Acknowledgment.–This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 12474358, No. 11974151, and No. 12247101).

References

- (1) D. Braak, Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 100401 (2011).

- (2) E. Solano, Physics 4, 68 (2011).

- (3) See a review of theoretical methods for light-matter interactions in A. Le Boité, Adv. Quantum Technol. 3, 1900140 (2020).

- (4) See a review of quantum phase transitions in light-matter interactions e.g. in J. Liu, M. Liu, Z.-J. Ying, and H.-G. Luo, Adv. Quantum Technol. 4, 2000139 (2021).

- (5) P. Forn-Díaz, L. Lamata, E. Rico, J. Kono, and E. Solano, Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 025005 (2019).

- (6) A. F. Kockum, A. Miranowicz, S. De Liberato, S. Savasta, and F. Nori, Nature Reviews Physics 1, 19 (2019).

- (7) H.-P. Eckle, Models of Quantum Matter (Oxford University, London, 2019)

- (8) J. Larson and T. Mavrogordatos, The Jaynes-Cummings Model and Its Descendants, IOP, London, (2021).

- (9) S. Ashhab, Phys. Rev. A 87, 013826 (2013).

- (10) Z.-J. Ying, M. Liu, H.-G. Luo, H.-Q.Lin, and J. Q. You, Phys. Rev. A 92, 053823 (2015).

- (11) M.-J. Hwang, R. Puebla, and M. B. Plenio, Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 180404 (2015).

- (12) M.-J. Hwang and M. B. Plenio, Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 123602 (2016).

- (13) J. Larson and E. K. Irish, J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 50, 174002 (2017).

- (14) M. Liu, S. Chesi, Z.-J. Ying, X. Chen, H.-G. Luo, and H.-Q. Lin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 220601 (2017).

- (15) Z.-J. Ying, L. Cong, and X.-M. Sun, arXiv:1804.08128, 2018; J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 53, 345301 (2020).

- (16) Z.-J. Ying, Phys. Rev. A 103, 063701 (2021).

- (17) Z.-J. Ying, Adv. Quantum Technol. 5, 2100088 (2022); ibid. 5, 2270013 (2022).

- (18) Z.-J. Ying, Adv. Quantum Technol. 5, 2100165 (2022).

- (19) Z.-J. Ying, Adv. Quantum Technol. 6, 2200068 (2023); ibid. 6, 2370011 (2023).

- (20) Z.-J. Ying, Adv. Quantum Technol. 6, 2200177 (2023); ibid. 6, 2370071 (2023).

- (21) Z.-J. Ying, Phys. Rev. A 109, 053705 (2024).

- (22) Z.-J. Ying, Adv. Quantum Technol. 7, 2400053 (2024); ibid. 7, 2470017 (2024).

- (23) Z.-J. Ying, Adv. Quantum Technol. 7, 2400288 (2024); ibid. 7, 2470029 (2024).

- (24) Z.-J. Ying, W.-L. Wang, and B.-J. Li, Phys. Rev. A 110, 033715 (2024).

- (25) R. Grimaudo, A. S. Magalhães de Castro, A. Messina, E. Solano, and D. Valenti, Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 043602 (2023).

- (26) R. Grimaudo, D. Valenti, A. Sergi, and A. Messina, Entropy 25, 187 (2023).

- (27) G.-L. Zhu, C.-S. Hu, H. Wang, W. Qin, X.-Y. Lü, and F. Nori, Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 193602 (2024).

- (28) L. Garbe, M. Bina, A. Keller, M. G. A. Paris, and S. Felicetti, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 120504 (2020).

- (29) L. Garbe, O. Abah, S. Felicetti, and R. Puebla, Phys. Rev. Research 4, 043061 (2022).

- (30) T. Ilias, D. Yang, S. F. Huelga, M. B. Plenio, PRX Quantum 3, 010354 (2022).

- (31) Z.-J. Ying, S. Felicetti, G. Liu, and D. Braak, Entropy 24, 1015 (2022).

- (32) V. Montenegro, U. Mishra, and A. Bayat, Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 200501 (2021).

- (33) Y. Chu, S. Zhang, B. Yu, and J. Cai, Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 010502 (2021).

- (34) C. Hotter, H. Ritsch, and K. Gietka, Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 060801 (2024).

- (35) D. Braak, Symmetry 11, 1259 (2019).

- (36) Q.-H. Chen, C. Wang, S. He, T. Liu, and K.-L. Wang, Phys. Rev. A 86, 023822 (2012).

- (37) J. Peng, J. Zheng, J. Yu, P. Tang, G. Alvarado Barrios, J. Zhong, E. Solano, F. Albarrán-Arriagada, and L. Lamata, Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 043604 (2021).

- (38) J. Peng, E. Rico, J. Zhong, E. Solano, and I. L. Egusquiza, Phys. Rev. A 100, 063820 (2019).

- (39) Q.-T. Xie, S. Cui, J.-P. Cao, L. Amico, and H. Fan, Phys. Rev. X 4, 021046 (2014).

- (40) E. K. Irish and A. D. Armour, Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 183603 (2022).

- (41) E. K. Irish and J. Gea-Banacloche, Phys. Rev. B 89, 085421 (2014).

- (42) Z.-M. Li, D. Ferri, D. Tilbrook, and M. T. Batchelor, J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 54, 405201 (2021).

- (43) Z. Wang, T. Jaako, P. Kirton, and P. Rabl, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 213601 (2020).

- (44) M. T. Batchelor and H.-Q. Zhou, Phys. Rev. A 91, 053808 (2015).

- (45) W. Qin, A. Miranowicz, P.-B. Li, X.-Y. Lü, J. Q. You, and F. Nori, Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 093601 (2018).

- (46) X.-F. Pan, P.-B. Li, X.-L. Hei, X. Zhang, M. Mochizuki, F.-L. Li, and F. Nori, Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 193601 (2024).

- (47) H. P. Eckle and H. Johannesson, J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 50, 294004 (2017); 56, 345302 (2023).

- (48) Y.-Q. Shi, L. Cong, and H.-P. Eckle, Phys. Rev. A 105, 062450 (2022).

- (49) K. K. W. Ma, Phys. Rev. A 102, 053709 (2020).

- (50) L.-T. Shen, Z.-B. Yang, H.-Z. Wu, and S.-B. Zheng, Phys. Rev. A 95, 013819 (2017).

- (51) Z. Lü, C. Zhao, and H. Zheng, J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 50, 074002 (2017).

- (52) Y. Yan, Z. Lü, L. Chen, and H. Zheng, Adv. Quantum Technol. 6, 2200191 (2023).

- (53) X. Y. Lü, L. L. Zheng, G. L. Zhu, and Y. Wu, Phys. Rev. Applied 9, 064006 (2018).

- (54) D. F. Padilla, H. Pu, G.-J. Cheng, and Y.-Y. Zhang, Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 183602 (2022).

- (55) Y. Wang, W.-L. You, M. Liu, Y.-L. Dong, H.-G. Luo, G. Romero, and J. Q. You, New J. Phys. 20, 053061 (2018).

- (56) G. Lyu, K. Kottmann, M. B. Plenio, and M.-J. Hwang, Phys. Rev. Research 6, 033075 (2024).

- (57) Z. Wu, C. Hu, T. Wang, Y. Chen, Y. Li, L. Zhao, X.-Y. Lü, and X. Peng, Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 173602 (2024).

- (58) S. Cheng, H.-G. Xu, X. Liu, and X.-L. Gao, Physica A 604, 127940 (2022).

- (59) H.-G. Xu, V. Montenegro, X.-L. Gao, J. Jin, and G. D. de Moraes Neto, Phys. Rev. Research 6, 013001 (2024).

- (60) W.-T. He, C.-W. Lu, Y.-X. Yao, H.-Y. Zhu, and Q. Ai, Front. Phys. 18, 31304 (2023).

- (61) J. Zhang, Y.-L. Zhou, Y. Zuo, H. Zhang, P.-X. Chen, H. Jing, and L.-M. Kuang, Adv. Quantum Technol. 7, 2300350 (2024).

- (62) S. Felicetti and A. Le Boité, Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 040404 (2020).

- (63) S. Felicetti, M.-J. Hwang, and A. Le Boité, Phy. Rev. A 98, 053859 (2018).

- (64) U. Alushi, T. Ramos, J. J. García-Ripoll, R. Di Candia, and S. Felicetti, PRX Quantum 4, 030326 (2023).

- (65) G. Liu, W. Xiong, and Z.-J. Ying, Phys. Rev. A 108, 033704 (2023).

- (66) D. Xu, X.-K. Gu, H.-K. Li, Y.-C. Weng, Y.-P. Wang, J. Li, H. Wang, S.-Y. Zhu, and J. Q. You, Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 193603 (2023).

- (67) G. Di Bello, A. Ponticelli, F. Pavan, V. Cataudella, G. De Filippis, A. de Candia, and C. A. Perroni, Commun. Phys. 7, 364 (2024).

- (68) H.-J. Zhu, K. Xu, G.-F. Zhang, and W.-M. Liu, Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 050402 (2020).

- (69) S. Felicetti, J. S. Pedernales, I. L. Egusquiza, G. Romero, L. Lamata, D. Braak, E. Solano, Phys. Rev. A 92, 033817 (2015).

- (70) L. Duan, Y.-F. Xie, D. Braak, Q.-H. Chen, J. Phys. A 49, 464002 (2016).

- (71) L. Garbe, I. L. Egusquiza, E. Solano, C. Ciuti, T. Coudreau, P. Milman, S. Felicetti, Phys. Rev. A 95, 053854 (2017).

- (72) S. Felicetti, D. Z. Rossatto, E. Rico, E. Solano, and P. Forn-Díaz, Phys. Rev. A 97, 013851 (2018).

- (73) L. Cong, X.-M. Sun, M. Liu, Z.-J. Ying, H.-G. Luo, Phys. Rev. A 99, 013815 (2019).

- (74) R. J. Armenta Rico, F. H. Maldonado-Villamizar, and B. M. Rodriguez-Lara, Phys. Rev. A 101, 063825 (2020).

- (75) A. Le Boité, M.-J. Hwang, H. Nha, and M. B. Plenio, Phys. Rev. A 94, 033827 (2016).

- (76) A. Ridolfo, M. Leib, S. Savasta, and M. J. Hartmann, Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 193602 (2012).

- (77) J. Casanova, R. Puebla, H. Moya-Cessa, and M. B. Plenio, npj Quantum Information 4, 47 (2018).

- (78) Z.-L. Xiang, S. Ashhab, J. Q. You, and F. Nori, Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 623 (2013). J. Q. You and F. Nori, Phys. Rev. B 68, 064509, (2003).

- (79) A. Wallraff, D. I. Schuster, A. Blais, L. Frunzio, R.-S. Huang, J. Majer, S. Kumar, S. M. Girvin, and R. J. Schoelkopf, Nature 431, 162 (2004).

- (80) C. Ciuti, G. Bastard, and I. Carusotto, Phys. Rev. B 72, 115303 (2005).

- (81) A. A. Anappara, S. De Liberato, A. Tredicucci, C. Ciuti, G. Biasiol, L. Sorba, and F. Beltram, Phys. Rev. B 79, 201303(R) (2009).

- (82) G. Günter, A. A. Anappara, J. Hees, A. Sell, G. Biasiol, L. Sorba, S. De Liberato, C. Ciuti, A. Tredicucci, A. Leitenstorfer, and R. Huber, Nature 458, 178 (2009).

- (83) P. Forn-Díaz, J. Lisenfeld, D. Marcos, J. J. Garcia-Ripoll, E. Solano, C. J. P. M. Harmans, and J. E. Mooij, Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 237001 (2010).

- (84) T. Niemczyk, F. Deppe, H. Huebl, E. P. Menzel, F. Hocke, M. J. Schwarz, J. J. Garcia-Ripoll, D. Zueco, T. Hümmer, E. Solano, A. Marx, and R. Gross, Nature Phys. 6, 772 (2010).

- (85) B. Peropadre, P. Forn-Díaz, E. Solano, and J. J. García-Ripoll, Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 023601 (2010).

- (86) G. Scalari, C. Maissen, D. Turčinková, D. Hagenmüller, S. De Liberato, C. Ciuti, C. Reichl, D. Schuh, W. Wegscheider, M. Beck, and J. Faist, Science 335, 1323 (2012).

- (87) P. Forn-Díaz, J. J. García-Ripoll, B. Peropadre, J. L. Orgiazzi, M. A. Yurtalan, R. Belyansky, C. M. Wilson, and A. Lupascu, Nat. Phys. 13, 39 (2017).

- (88) X. Gu, A. F. Kockum, A. Miranowicz, Y. X. Liu, and F. Nori, Phys. Rep. 718-719, 1 (2017).

- (89) J.-F. Huang, J.-Q. Liao, and L.-M. Kuang, Phys. Rev. A 101, 043835 (2020).

- (90) A. Stokes and A. Nazir, Nat. Commun. 10, 499 (2019).

- (91) F. Yoshihara, T. Fuse, S. Ashhab, K. Kakuyanagi, S. Saito, and K. Semba, Nat. Phys. 13, 44 (2017).

- (92) A. Bayer, M. Pozimski, S. Schambeck, D. Schuh, R. Huber, D. Bougeard, and C. Lange, Nano Lett. 17, 6340 (2017).

- (93) J. Casanova, G. Romero, I. Lizuain, J. J. García-Ripoll, and E. Solano, Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 263603 (2010).

- (94) C. Liu, and J.-F. Huang, Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 67, 210311 (2024).

- (95) X. Chen, Z. Wu, M. Jiang, X.-Y. Lü, X. Peng, and J. Du, Nat. Commun. 12, 6281 (2021).

- (96) C. L. Degen, F. Reinhard, and P. Cappellaro, Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

- (97) L. Maccone and A. Riccardi, Quantum 4, 292 (2020).

- (98) B. J. Lawrie, P. D. Lett, A. M. Marino, and R. C. Pooser, ACS Photonics 6, 1307 (2019).

- (99) K. Gietka and H. Ritsch, Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 090802 (2023).

- (100) K. Gietka, C. Hotter, and H. Ritsch, Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 223604 (2023).

- (101) L. Pezzè, A. Smerzi, M. K. Oberthaler, R. Schmied, and P. Treutlein, Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 035005 (2018).

- (102) K. Gietka, Phys. Rev. A 105, 042620 (2022).

- (103) D. Braak, Q.H. Chen, M.T. Batchelor, and E. Solano, J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 49, 300301 (2016).

- (104) I. I. Rabi, Phys. Rev. 51, 652 (1937).

- (105) V. V. Mangazeev, M. T. Batchelor, and V. V. Bazhanov, J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 54, 12LT01 (2021).

- (106) Z.-M. Li and M. T. Batchelor, Phys. Rev. A 103, 023719 (2021).

- (107) C. Reyes-Bustos, D. Braak, and M. Wakayama, J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 54, 285202 (2021).

- (108) J. E. Mooij, T. P. Orlando, L. Levitov, L. Tian, and C. H. van der Wal, S. Lloyd, Science 285, 1036 (1999).

- (109) S. L. Braunstein and C. M. Caves, Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3439 (1994).

- (110) M. M. Taddei, B. M. Escher, L. Davidovich, and R. L. de Matos Filho, Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 050402 (2013).

- (111) M. M. Rams, P. Sierant, O. Dutta, P. Horodecki, and J. Zakrzewski, Phys. Rev. X 8, 021022 (2018).

- (112) A. I. Lvovsky, Photonics Volume 1: Fundamentals of Photonics and Physics, pp. 121-164 Edited by D. Andrews, Wiley, West Sussex, United Kingdom, 2015.

- (113) H.-Q. Zhou and J. P. Barjaktarevi, J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 41 412001 (2008).

- (114) S.-J. Gu, Int. J. of Mod. Phys. B 24 4371, (2010).

- (115) W.-L. You, Y.-W. Li, and S.-J. Gu, Phys. Rev. E 76, 022101 (2007).

- (116) W.-L. You and L. He, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 27, 205601 (2015).

- (117) P. Zanardi and N. Paunkovi, Phys. Rev. E 74, 031123 (2006).