Absence of superconductivity in electron-doped chromium pnictides ThCrAsN1-xOx

Abstract

Theoretical studies predicted possible superconductivity in electron-doped chromium pnictides isostructural to their iron counterparts. Here, we report the synthesis and characterization of a new ZrCuSiAs-type Cr-based compound ThCrAsN, as well as its oxygen-doped variants. All samples of ThCrAsN1-xOx show metallic conduction, but no superconductivity is observed above 30 mK even though the oxygen substitution reaches 75%. The magnetic structure of ThCrAsN is determined to be G-type antiferromagnetic by magnetization measurements and first-principles calculations jointly. The calculations also indicate that the in-plane Cr–Cr direct interaction of ThCrAsN is robust against the heavy electron doping. The calculated density of states of the orbital occupations of Cr for ThCrAs(N,O) is strongly spin-polarized. Our results suggest the similarities between chromium pnictides and iron-based superconductors shouldn’t be overestimated.

pacs:

I Introduction

Since the discovery of high- superconductivity in Fe-based materials [1], tremendous efforts have been devoted to search for superconductivity in the Fe-free transition-metal systems with the conducting layers isostructural to Fe ( = As or Se) motifs [2, 3]. Among them Cr2As2-layer-based compounds are of particular interest because they exhibit antiferromagnetism with high Neel temperature [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11], even though Cr-based superconductors are scarce due to the robustness of antiferromagnetism [12]. The exploration of superconductivity in Cr2As2-layer-based materials is not only inspired by the breakthrough in Cr-based superconductors in recent years [13, 14, 15, 16, 17], but also supported by the theoretical predictions [18, 19, 20].

Within the framework of the Mott scenario for the transition-metal arsenides [21], the case of Cr2+ is symmetrical to the case of Fe2+ with respect to half-filled configuration (Mn2+). In this context, Fe-based superconductors (FeSCs) are electron-doped systems compared to the Mott-type parent materials. Accordingly, Cr-based compounds are expected to show comparable electronic correlations with possible superconductivity as the hole-doped side to the system, when the fillings is between and [19, 20]. That is to say, electron doping in the configuration is likely to bring about superconductivity in Cr2As2-based materials.

However, it’s not easy to find a proper Cr2As2-based compound to study the electron-doping effect systematically. With regard to LaCrAsO, the solid solubility limits F- substitution for O2- to 20% [4], while H- doping results in the structural transformation [22]. In addition, the replacements of Cr site by Mn and Fe lead to a metal–insulator transition in LaCrAsO and BaCr2As2, respectively [4, 23].

In this work, we report a new chromium pnictide, ThCrAsN, which is isostructural to LaCrAsO. The advantage of Th2N2 layers over La2O2 layers is the high solubility of O2- in N3-, making high electron doping possible [24, 25, 26]. A series of polycrystalline samples of ThCrAsN1-xOx were synthesized, and the actual O2- doping concentration could be as high as 75%. All the ThCrAsN1-xOx samples exhibit metallic electrical conduction. Nevertheless, none of the samples shows superconductivity above 30 mK, against the theoretical predictions. [19, 20] Magnetic measurements and density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicate that ThCrAsN is G-type antiferromagnetic (AFM), the same as other reported Cr2As2-based compounds [4, 23, 7, 6]. And the magnetic structure of the hypothetical end member ThCrAsO, though unavailable, is also a G-type antiferromagnet within the DFT calculations, indicating the robustness of AFM order that hinder the appearance of superconductivity. From our results and analysis, the materials with Cr2As2 layers seem not to be a simple symmetry of FeSCs with respect to half 3 shell filling.

II Methods

Samples preparation. Polycrystalline samples of ThCrAsN1-xOx () were synthesized using powder of Th3N4, Th3As4, ThO2, Cr and CrAs as starting materials. CrAs was prepared with Cr powder (99.99%) and As pieces (99.999%) and at 750∘C in evacuated quartz tubes. ThO2 was heated to 700∘C for 12 h in the furnace to remove absorbed water. Preparation of the thorium metal ingot, Th3N4 powder and Th3As4 powder were described elsewhere [24, 27, 28]. Stoichiometric mixture of the starting materials was ground and cold-pressed into a pellet. The pellet was loaded in an alumina crucible, which was sealed in an evacuated quartz tube. Subsequently, the tube was heated to 1100∘C in a muffle furnace, holding for 50 hours. The final product is dark grey and stable in air.

Powder X-ray Diffraction. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments were carried out at room temperature on a PANalytical X-ray diffractometer with Cu radiation. XRD data were collected in the range with a step of 0.013∘. The FullProf suite was used for the structural refinements [29].

Resistivity and Magnetization Measurements. A standard four-probe method was employed to collect the resistivity data. The data above 2 K were measured using a Quantum Design Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) Dynacool, while the measurements between 30 mK and 0.8 K were performed in a dilution refrigerator. The direct-current (dc) magnetization was measured on a Quantum Design Magnetic Property Measurement System (MPMS3) equipped with the oven option.

First-Principles Calculations. The first-principles calculations were done within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) by using the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) [30]. The experimental crystal structure was used for the calculations. The plane-wave basis energy cutoff was chosen to be 550 eV. A -centered K-mesh was used for the density-of-states (DOS) calculations. The Coulomb- and exchange parameters, and , were introduced by using the GGA+ calculations, where the parameters and are not independent and the difference () is meaningful. We adopted a GGA+ ( = 11 eV) correction on Th- shell to prevent unphysical 5 component at Fermi level [4, 31]. And was chosen at 0 eV for Cr 3.

III RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

III.1 Crystal structure

| Atom | Wyckoff | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.1341(1) | 0.1 | |

| Cr | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.3 | |

| As | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.6673(3) | 0.3 | |

| N | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 | |

| Compounds | ThCrAsN | LaCrAsO [4] | |||

| Lattice parameters | |||||

| (Å) | 4.0290(1) | 4.0412(3) | |||

| (Å) | 8.8522(3) | 8.9863(7) | |||

| (Å3) | 143.70(1) | 146.76(2) | |||

| 2.197 | 2.224 | ||||

| Selected distances | |||||

| (Å) | 1.481(3) | 1.460(2) | |||

| (Å) | 2.338(1) | 2.364(1) | |||

| (Å) | 2.500(2) | 2.494(1) | |||

| (Å) | 2.8489(1) | 2.8576(3) | |||

| Bond angle | |||||

| AsCrAs (∘) | 107.36(10) | 108.26(8) | |||

The XRD patterns of ThCrAsN and its oxygen-doped variants are displayed in Figs. 1(a) and (b). The pattern of ThCrAsN can be indexed well using space group , indicating the successful preparation of the parent compound. Element substitutions of oxygen for nitrogen are carried out, ranging from 10% oxygen to 100% oxygen, and the doping step is equal to 10%. With increasing oxygen concentration, the impurity peaks emerge and become conspicuous. The impurities of Th3As4 (for ), ThO2 (for ), and Cr2As (for ) can be identified, as well as some unknown impurity phase(s) (only for ). However, ThCrAsN1-xOx remains the main phase even though the nominal concentration of oxygen is as high as 80%. Even for the pattern of , the phase of 1111 is conspicuous enough to examine the existence of superconductivity. A simple estimation of the ratio between the 1111 phase and ThO2 is presented in Supplemental Materials (SM) [32]. With regard to the wholly doped sample, i.e. ThCrAsO, no ZrCuSiAs-type phase can be identified. It’s proper to believe ThCrAsO can not be synthesized under the present synthesis conditions.

In Fig. 1(b), two tilted green bars are sketched to show the monotonic shift of the (111) peaks and (200) peaks, suggesting the unit cell of ThCrAsN1-xOx decreases gradually with the increase of oxygen doping. By a least-squares fit for the XRD patterns, the lattice parameters of ThCrAsN1-xOx are determined and plotted as functions of nominal oxygen concentration in Fig. 1(c). Both the -axis and -axis decrease almost linearly with increasing when , as indicated by the green bars on the data points. The dependences of cell parameters on deviate from the green bars gradually when , indicating the real oxygen concentration is lower than the nominal doping , in line with the increasing impurity of ThO2 in panel (b). If we take the slopes of and () as reference, the real oxygen concentration for the sample of ThCrAsN0.1O0.9 is about 0.75, inferred from its cell parameters. It is worth noting that the change of the -axis is about 1.75% from to 0.9, while the -axis only shrinks by 1.13%. That the -axis changes much faster than the -axis is consistent with the enhanced inter-layer coupling by electron doping.

A Rietveld refinement was carried out using the collected XRD data shown in Fig. 1(a). The refinement yields a weighted reliable factor of and a goodness-of-fit of , indicating reliability of the refinement. The resulting crystallographic data were summarized in Table 1, and compared with the selected structural parameters of LaCrAsO. The axial ratio of ThCrAsN is smaller than that of LaCrAsO, implying ThCrAsN bears stronger internal chemical pressure along the -axis. Similar reduction of was also observed in other siblings ThAsN and LaAsO ( = Mn, Fe, Ni, Co) [24, 28, 27, 33]. Other structural parameters of ThCrAsN, such as the height of As from Cr plane and AsCrAs bond angle, are not distinct from those of LaCrAsO, which accounts for their close properties.

III.2 Electrical resistivity

The resistivity data () for ThCrAsN1-xOx are plotted in Fig. 2. As seen in Fig. 2(a), curves show a similar metallic behavior, regardless of the doping concentration. The magnitudes of resistivity are about 1 m cm at room temperature, comparable to that of LaCrAsO [4]. Only the samples of = 0.8 and 0.9 show a slightly higher resistivity due to the increased impurity proportion. Although the measured values of resistivity are affected by the contacts and impurity, the residual resistivity ratios (RRR) for all samples are between 2 and 3. The data below 20 K for 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, and 0.7 are enlarged in the inset of Fig. 2(a) so that the curves differentiate from each other. It’s easily noticed that all curves but approach to constant values at 2 K. To examine the possibility that superconductivity emerges under lower temperatures, we measured (30 mK 0.8 K) of several selected compounds in the dilution refrigerator, which are displayed in Fig. 2(b). However, the data of are almost constant below 0.8 K and show no signs for superconductivity. Hence, superconductivity can’t be induced in ThCrAsN1-xOx even thogh the real electron doping concentration is as high as 0.75 (), against the prediction of a superconductivity phase at [20].

III.3 Magnetic properties

Figure 3(a) shows the curve for the parent compound ThCrAsN under the magnetic field 1 T and there is no difference between zero-field-cooling and field-cooling data. Below 160 K, the susceptibility shows a Curie-Weiss-like tail, which may be caused by trace amount of paramagnetic impurity. Above 160 K, the susceptibility increases with the temperature monotonically and shows a gentle slope around 850 K, suggesting ThCrAsN is an antiferromagnet. The behavior of ThCrAsN is reminiscent of the cases for polycrystalline SrCr2As2, which also shows no Curie-Weiss behavior below 900 K and no clear AFM transition [7]. In addition, LaCrAsO only shows a smooth maximum at K [4]. The behaviors of for these Cr2As2-based materials are considered as the character of a two-dimensional (2D) antiferromagnet, which means that strong 2D AFM correlations may set in well above the ordering temperature () [4]. Since the actual could be notably lower than the maximum in the susceptibility for 2D AFM compounds, here we use the derivative to extract of ThCrAsN, as plotted in the inset [34, 35, 7]. shows an AFM transition peak at about 630 K, indicating of ThCrAsN is fall on same level with most Cr2As2-based materials [7, 23, 36, 4, 37].

for ThCrAsN0.9O0.1 under 1 T is displayed in Fig. 3(b), which is quite akin to that of ThCrAsN. Yet the AFM order wasn’t suppressed by the oxygen doping. As shown in the inset of Fig. 3(b), of ThCrAsN0.9O0.1 is determined to be K from , even higher than the parent. In addition, the susceptibility maximum of ThCrAsN0.9O0.1 appears at higher temperature than ThCrAsN, indicative of stronger 2D correlations. curves for other ThCrAsN1-xOx samples are shown in Fig. S2 in SM [32]. Unfortunately, the susceptibility data for other samples are not informative because of the strong background from the robust magnetic impurities. Nevertheless, we can still draw the conclusion that the susceptibility data show no sign of Meissner effect in ThCrAsN1-xOx.

III.4 Magnetic energies

To determine the magnetic structure of ThCrAsN and its oxygen-doped derivatives, we examined the magnetic energies () for several possible AFM structures by performing DFT calculations. is defined as the energy difference between the spin-polarized state and nonmagnetic state. The selected spin configurations are presented in Fig. 4, as well as the corresponding and Cr spin moments. and Cr spin moments are calculated for both ThCrAsN and ThCrAsO, in spite of the failure of synthesis for the latter.

As shown in Fig. 4(a), all magnetic orders lower the total energy of ThCrAsN, compared to the nonmagnetic state. Among them G-type AFM order is the most stable magnetic structure, yet C-type spin configuration has a pretty close energy. The similar values for G-type and C-type AFM orders demonstrate the interplane spin coupling for ThCrAsN is weak, consistent with the characteristic of 2D AFM order. Note that the calculated of G-type and C-type AFM orders for LaCrAsO are also reported to be close [4]. And the spin structure of LaCrAsO is experimentally determined to be G-type. Based on the comparable behaviors of and results of calculations, it’s plausible to anticipate that ThCrAsN has a G-type order, like LaCrAsO. In addition, the G-type AFM order were found to be the ground state for Cr-based 122-type coumpouds like BaCr2As2, BaCr2P2, SrCr2As2, EuCr2As2, Sr2Cr3As2O2, and Sr2Cr2AsO3 [23, 7, 6, 38, 8, 11], which also supports our speculation of the magnetic structure of ThCrAsN.

To gain a deeper insight into the magnetic ordering of ThCrAsN, we calculate the exchange interactions between the Cr neighbors in light of a simple Heisenberg model [39]. The magnetic energies of C-type, G-type and S-type AFM orderings can be expressed as

| (1) | |||

| (2) | |||

| (3) |

where is the local spin, and refer to the interactions of in-plane nearest-neighbor, in-plane next-nearest-neighbor, out-of-plane nearest-neighbor, respectively. The values of energies for ThCrAsN could be found in the Table S2 in the SM [32]. Solutions of the equations are

| (4) | |||

| (5) | |||

| (6) |

Assuming the Cr spin moment of ThCrAsN is 2.5 (, according to Fig. 4(a)), the resulting interactions are = 187.9 meV, = 62.1 meV, = 0.66 meV, consistent with the stability conditions of G-type AFM order that , , and . The small positive value confirms the AFM coupling between the adjacent Cr2As2 layers is weak, in good agreement with the behavior. The large positive values of and indicate that in-plane Cr–Cr direct interaction is dominant, thus the high Neel temperature and robust G-type AFM order is explicit. We also notice that the calculated energies , , and for ThCrAsN, as well as the Cr moment, are all close to the values for LaCrAsO [4]. Hence the resultant and are almost the same as the interactions for ThCrAsN.

and Cr spin moments of ThCrAsO ( for Cr, one electron more compared to ThCrAsN) with the same magnetic structures as ThCrAsN are shown in Fig. 4(b). The calculation indicates that G-type order is still the ground state of ThCrAsO, although its is significantly lower than ThCrAsN. And the corresponding Cr spin moment is reduced slightly to be 2.43 . That is to say, AFM order of ThCrAsN is to a certain extent suppressed by electron doping. However, the G-type magnetic order remains for the end member ThCrAsO.

Here we would like to point out that and values for LaFeAsO both are about 50 meV/, which are close and conspicuously smaller than the values for ThCrAsN [40]. The competition of exchange interactions in FeSCs lead to the collinear (or bicollinear) AFM order, contrary to the case for ThCrAsN. And the next-nearest-neighbor interaction is generally believed to play an important role in the electron pairing mechanism of FeSCs [41, 42]. The magnetic structures and exchange interactions clearly point to the distinction between Cr2As2-based materials and FeSCs.

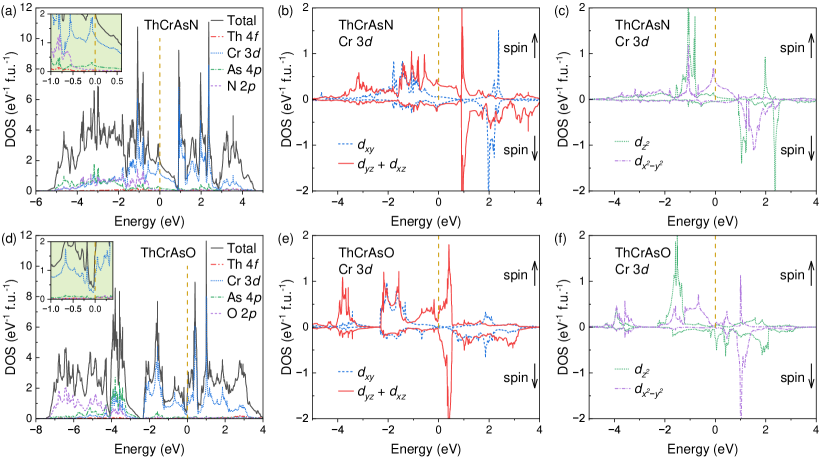

III.5 Density of states

The total density of states (DOS) of G-type AFM ordered ThCrAsN and ThCrAsO are calculated and plotted in Fig. 5, as well as their projected density of states (PDOS) of Cr-3 orbitals. Both ThCrAsN and ThCrAsO show a relatively large DOS at the Fermi energy (), coinciding with the typical metallic behavior of ThCrAsN1-xOx. As shown in Fig. 5(a), the DOS of ThCrAsN around is mainly contributed by Cr-3 and As-4 orbitals. And it is easy to recognize the modest hybridizations between Cr-3 and As-4 in the inset. The hybridizations account for the itinerant magnetism and the reduced Cr-3 magnetic moment of ThCrAsN (theoretically 4 for Cr2+).

DOS of ThCrAsO is shown in Fig. 5(d). DOSs for ThCrAsN and ThCrAsO are largely comparable, and of ThCrAsO shifts to higher position due to its nominal Cr-3 electron configuration. The similarities of DOSs can be seen better in other panels about PDOS of Cr. Cr-3 electrons still dominate the states around of ThCrAsO, but the hybridizations between Cr-3 and As-4 is negligible compared to ThCrAsN.

To compare the PDOS of Cr-3 orbitals for ThCrAsN and ThCrAsO more clearly, we divide the orbitals into two groups and present the curves in Figs. 5(b)(e) (, ) and (c)(f) (, ), respectively. The itinerant magnetism of ThFeAsN and ThFeAsO is confirmed by the broad energy bands. We notice that the orbital occupations of Cr for both ThCrAsN and ThCrAsO are highly spin-polarized, indicating the crystal field splitting energy is small so that Hund’s rule is followed. The high-spin state is also observed for LaCrAsO and LaMnAsO, while the spin polarization for LaFeAsO is much weaker [4, 40]. For ThCrAsN, the PDOS at comes from all five 3 orbitals, and the and contribute substantially. The heavy proportion of orbital means enhanced direct exchange at , consistent with the G-type AFM order that is favored by the nearest Cr–Cr interactions. After the replacement of nitrogen by oxygen, the DOS of and decline sharply, meanwhile the contributions from increase significantly, preceded only by . Whether for ThCrAsN or ThCrAsO, there is a heavy mixing of the and orbitals at , which is deemed detrimental to high- superconductivity in some theoretical work [43].

IV Concluding Remarks

To summarize, we have successfully synthesized a new 1111-type material, ThCrAsN. Then we explored the possibility of superconductivity by electron-doping in ThCrAsN through O2- substitution for N3-. However, ThCrAsN1-xOx shows no sign of superconductivity with the oxygen concentration from 0 to 75%, inconsistent with the theoretical predictions. Magnetic susceptibility of ThCrAsN indicates its AFM ground states with an ordering temperature about 630 K, and DFT calculations imply the most probable spin structure for ThCrAsN and the doped variants is G-type, the same as LaCrAsO and Cr2As2 ( = Sr, Ba, Eu), although further examination of the magnetic structure with powder neutron scattering is still required. The analysis of the exchange interactions between Cr neighbors indicates in-plane direct interaction is dominant, resulting in the robust G-type AFM order of ThCrAs(N,O). Although the superconductivity couldn’t be induced by electron doping in ThCrAsN, the AFM order is moderately suppressed, manifested by the reduced magnetic energy and Cr spin moment of ThCrAsO. In addition, the PDOSs of Cr show that the spin polarization for ThCrAsN and ThCrAsO is strong, which is a major difference from the DOS of LaFeAsO.

Since the pairing mechanism in FeSCs is still under debate, it’s hard to elucidate the reasons for absence of superconductivity in electron-doped ThCrAsN. Nevertheless, the distinctions between Cr2As2-based materials and FeSCs are explicit. In general, high- superconductivity develops after a magnetic ordering is suppressed, suggesting the interplay between superconductivity and magnetism is crucial. G-type AFM order is usually found to be the ground state for Cr2As2-based compounds, which is apparently distinguished from collinear or bicollinear AFM orders for FeSCs. Essentially, the exchange interactions between Cr (or Fe) neighbors shape the magnetic structures and may be related to the superconducting pairing. And the different spin polarizations for FeSCs and Cr-based materials are also not inconsiderable. In addition, the electronic correlations may play an important role as well. In fact, an angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy study shows that BaCr2As2 is much less correlated than BaFe2As2 [44]. The absence of superconductivity in Cr2As2-based materials calls for an indepth theoretical explanation.

Although the comparability of Cr-based compounds and Fe-based counterparts is highlighted in some theoretical works based on the doped-Mott scenario, their similarities shouldn’t be overestimated in respect of our work and other available experiments. Yet the possibility of superconductivity in Cr-based materials is not ruled out. We hope further experiments, like high-pressure measurements and hole doping in the synthesis, will suppress the magnetic ordering and give rise to superconductivity in Cr2As2-based materials.

Acknowledgements.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 12204094 and No. 12050003), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1403202), the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province, China (Grant No. 2021C01002), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20220796), and the open research fund of Key Laboratory of Quantum Materials and Devices (Southeast University), Ministry of Education.References

- Kamihara et al. [2008] Y. Kamihara, T. Watanabe, M. Hirano, and H. Hosono, Iron-based layered superconductor La[O1-xFx]FeAs () with K, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3296 (2008).

- Johrendt et al. [2011] D. Johrendt, H. Hosono, R.-D. Hoffmann, and R. Pöttgen, Structural chemistry of superconducting pnictides and pnictide oxides with layered structures, Z. Kristallogr. 226, 435 (2011).

- Shatruk [2019] M. Shatruk, ThCr2Si2 structure type: The “perovskite” of intermetallics, J. Solid State Chem. 272, 198 (2019).

- Park et al. [2013] S.-W. Park, H. Mizoguchi, K. Kodama, S.-i. Shamoto, T. Otomo, S. Matsuishi, T. Kamiya, and H. Hosono, Magnetic Structure and Electromagnetic Properties of LnCrAsO with a ZrCuSiAs-type Structure (Ln = La, Ce, Pr, and Nd), Inorg. Chem. 52, 13363 (2013).

- Singh et al. [2009] D. J. Singh, A. S. Sefat, M. A. McGuire, B. C. Sales, D. Mandrus, L. H. VanBebber, and V. Keppens, Itinerant antiferromagnetism in : Experimental characterization and electronic structure calculations, Phys. Rev. B 79, 094429 (2009).

- Paramanik et al. [2014] U. B. Paramanik, R. Prasad, C. Geibel, and Z. Hossain, Itinerant and local-moment magnetism in single crystals, Phys. Rev. B 89, 144423 (2014).

- Das et al. [2017] P. Das, N. S. Sangeetha, G. R. Lindemann, T. W. Heitmann, A. Kreyssig, A. I. Goldman, R. J. McQueeney, D. C. Johnston, and D. Vaknin, Itinerant G-type antiferromagnetic order in , Phys. Rev. B 96, 014411 (2017).

- Jiang et al. [2015] H. Jiang, J.-K. Bao, H.-F. Zhai, Z.-T. Tang, Y.-L. Sun, Y. Liu, Z.-C. Wang, H. Bai, Z.-A. Xu, and G.-H. Cao, Physical properties and electronic structure of containing and square-planar lattices, Phys. Rev. B 92, 205107 (2015).

- Pavan Kumar Naik et al. [2021] S. Pavan Kumar Naik, Y. Iwasa, K. Kuramochi, Y. Ichihara, K. Kishio, K. Hongo, R. Maezono, T. Nishio, and H. Ogino, Synthesis, electronic structure, and physical properties of layered oxypnictides Sr2ScCrAsO3 and Ba3Sc2Cr2As2O5, Inorg. Chem. 60, 1930 (2021).

- Ablimit et al. [2017] A. Ablimit, Y.-L. Sun, H. Jiang, J.-K. Bao, H.-F. Zhai, Z.-T. Tang, Y. Liu, Z.-C. Wang, C.-M. Feng, and G.-H. Cao, Synthesis, crystal structure and physical properties of a new oxypnictide Ba2Ti2Cr2As4O containing [Ti2As2O]2- and [Cr2As2]2- layers, J. Alloys Compd. 694, 1149 (2017).

- Lin et al. [2022] Y.-Q. Lin, H. Jiang, H.-X. Li, S.-J. Song, S.-Q. Wu, Z. Ren, and G.-H. Cao, Structural, electronic, and physical properties of a new layered Cr-based oxyarsenide Sr2Cr2AsO3, Materials 15, 802 (2022).

- Chen and Wang [2018] R. Y. Chen and N. L. Wang, Progress in Cr- and Mn-based superconductors: a key issues review, Rep. Prog. Phys. 82, 012503 (2018).

- Wu et al. [2014] W. Wu, J. Cheng, K. Matsubayashi, P. Kong, F. Lin, C. Jin, N. Wang, Y. Uwatoko, and J. Luo, Superconductivity in the vicinity of antiferromagnetic order in CrAs, Nat. Commun. 5, 5508 (2014).

- Bao et al. [2015] J.-K. Bao, J.-Y. Liu, C.-W. Ma, Z.-H. Meng, Z.-T. Tang, Y.-L. Sun, H.-F. Zhai, H. Jiang, H. Bai, C.-M. Feng, Z.-A. Xu, and G.-H. Cao, Superconductivity in Quasi-One-Dimensional with Significant Electron Correlations, Phys. Rev. X 5, 011013 (2015).

- Mu et al. [2017] Q.-G. Mu, B.-B. Ruan, B.-J. Pan, T. Liu, J. Yu, K. Zhao, G.-F. Chen, and Z.-A. Ren, Superconductivity at 5 K in quasi-one-dimensional Cr-based single crystals, Phys. Rev. B 96, 140504(R) (2017).

- Xiang et al. [2019] J.-J. Xiang, Y.-L. Yu, S.-Q. Wu, B.-Z. Li, Y.-T. Shao, Z.-T. Tang, J.-K. Bao, and G.-H. Cao, Superconductivity induced by aging and annealing in , Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 114802 (2019).

- Wu et al. [2019] W. Wu, K. Liu, Y. Li, Z. Yu, D. Wu, Y. Shao, S. Na, G. Li, R. Huang, T. Xiang, and J. Luo, Superconductivity in chromium nitrides Pr3Cr10-xN11 with strong electron correlations, Natl. Sci. Rev. 7, 21 (2019).

- Edelmann et al. [2017] M. Edelmann, G. Sangiovanni, M. Capone, and L. de’ Medici, Chromium analogs of iron-based superconductors, Phys. Rev. B 95, 205118 (2017).

- Pizarro et al. [2017] J. M. Pizarro, M. J. Calderón, J. Liu, M. C. Muñoz, and E. Bascones, Strong correlations and the search for high- superconductivity in chromium pnictides and chalcogenides, Phys. Rev. B 95, 075115 (2017).

- Wang et al. [2017a] W.-S. Wang, M. Gao, Y. Yang, Y.-Y. Xiang, and Q.-H. Wang, Possible superconductivity in the electron-doped chromium pnictide LaOCrAs, Phys. Rev. B 95, 144507 (2017a).

- Ishida and Liebsch [2010] H. Ishida and A. Liebsch, Fermi-liquid, non-Fermi-liquid, and Mott phases in iron pnictides and cuprates, Phys. Rev. B 81, 054513 (2010).

- Park et al. [2017] S.-W. Park, H. Mizoguchi, H. Hiraka, K. Ikeda, T. Otomo, and H. Hosono, Transformation of the chromium coordination environment in LaCrAsO induced by hydride doping: Formation of La2Cr2As2OyHx, Inorg. Chem. 56, 13642 (2017).

- Filsinger et al. [2017] K. A. Filsinger, W. Schnelle, P. Adler, G. H. Fecher, M. Reehuis, A. Hoser, J.-U. Hoffmann, P. Werner, M. Greenblatt, and C. Felser, Antiferromagnetic structure and electronic properties of and , Phys. Rev. B 95, 184414 (2017).

- Wang et al. [2016] C. Wang, Z.-C. Wang, Y.-X. Mei, Y.-K. Li, L. Li, Z.-T. Tang, Y. Liu, P. Zhang, H.-F. Zhai, Z.-A. Xu, and G.-H. Cao, A new ZrCuSiAs-type superconductor: ThFeAsN, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2170 (2016).

- Li et al. [2018] B.-Z. Li, Z.-C. Wang, J.-L. Wang, F.-X. Zhang, D.-Z. Wang, F.-Y. Zhang, Y.-P. Sun, Q. Jing, H.-F. Zhang, S.-G. Tan, Y.-K. Li, C.-M. Feng, Y.-X. Mei, C. Wang, and G.-H. Cao, Peculiar phase diagram with isolated superconducting regions in ThFeAsN1-xOx, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 30, 255602 (2018).

- Shao et al. [2019] Y.-T. Shao, Z.-C. Wang, B.-Z. Li, S.-Q. Wu, J.-F. Wu, Z. Ren, S.-W. Qiu, C. Rao, C. Wang, and G.-H. Cao, BaTh2Fe4As4(N0.7O0.3)2: An iron-based superconductor stabilized by inter-block-layer charge transfer, Sci. China Mater. 62, 1357 (2019).

- Wang et al. [2017b] Z.-C. Wang, Y.-T. Shao, C. Wang, Z. Wang, Z.-A. Xu, and G.-H. Cao, Enhanced superconductivity in ThNiAsN, EPL 118, 57004 (2017b).

- Zhang et al. [2020] F. Zhang, B. Li, Q. Ren, H. Mao, Y. Xia, B. Hu, Z. Liu, Z. Wang, Y. Shao, Z. Feng, S. Tan, Y. Sun, Z. Ren, Q. Jing, B. Liu, H. Luo, J. Ma, Y. Mei, C. Wang, and G.-H. Cao, ThMnPnN (Pn = P, As): Synthesis, structure, and chemical pressure effects, Inorg. Chem. 59, 2937 (2020).

- Rodríguez-Carvajal [1993] J. Rodríguez-Carvajal, Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction, Phys. B: Condens. Matter 192, 55 (1993).

- Kresse and Furthmüller [1996] G. Kresse and J. Furthmüller, Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set, Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

- Ueda et al. [2004] K. Ueda, H. Hosono, and N. Hamada, Energy band structure of LaCuOCh (Ch = S, Se and Te) calculated by the full-potential linearized augmented plane-wave method, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 16, 5179 (2004).

- [32] See the Supplemental Material for X-ray diffraction for ThCrAsN0.9O0.1, crystallographic data of ThFeAsN0.9O0.1 at 300 K, magnetic susceptibility for ThCrAsN1-xOx (), calculated magnetic energies and Cr spin moments for ThCrAsO, and band structures of ThCrAsN and ThCrAsO.

- Wang et al. [2020] J. Wang, F. Jiao, X. Wang, S. Zhu, L. Cai, C. Yang, P. Song, F. Zhang, B. Li, Y. Li, J. Hu, S. Li, Y. Li, S. Tan, Y. Mei, Q. Jing, C. Wang, B. Liu, and D. Qian, The phase transition of ThFe1-xCoxAsN from superconductor to metallic paramagnet, EPL 130, 67003 (2020).

- Fisher [1962] M. E. Fisher, Relation between the specific heat and susceptibility of an antiferromagnet, Philos. Mag. 7, 1731 (1962).

- de Jongh and Miedema [1974] L. de Jongh and A. Miedema, Experiments on simple magnetic model systems, Adv. Phys. 23, 1 (1974).

- Nandi et al. [2016] S. Nandi, Y. Xiao, N. Qureshi, U. B. Paramanik, W. T. Jin, Y. Su, B. Ouladdiaf, Z. Hossain, and T. Brückel, Magnetic structures of the Eu and Cr moments in : Neutron diffraction study, Phys. Rev. B 94, 094411 (2016).

- Liu et al. [2018] J. Liu, J. Wang, J. Sheng, F. Ye, K. M. Taddei, J. A. Fernandez-Baca, W. Luo, G.-A. Sun, Z.-C. Wang, H. Jiang, G.-H. Cao, and W. Bao, Neutron diffraction study on magnetic structures and transitions in , Phys. Rev. B 98, 134416 (2018).

- Jishi et al. [2019] R. A. Jishi, J. P. Rodriguez, T. J. Haugan, and M. A. Susner, Prediction of antiferromagnetism in barium chromium phosphide confirmed after synthesis, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 32, 025502 (2019).

- Johnston et al. [2011] D. C. Johnston, R. J. McQueeney, B. Lake, A. Honecker, M. E. Zhitomirsky, R. Nath, Y. Furukawa, V. P. Antropov, and Y. Singh, Magnetic exchange interactions in : A case study of the -- heisenberg model, Phys. Rev. B 84, 094445 (2011).

- Ma et al. [2008] F. Ma, Z.-Y. Lu, and T. Xiang, Arsenic-bridged antiferromagnetic superexchange interactions in LaFeAsO, Phys. Rev. B 78, 224517 (2008).

- Yu and Li [2012] S.-L. Yu and J.-X. Li, Chiral superconducting phase and chiral spin-density-wave phase in a hubbard model on the kagome lattice, Phys. Rev. B 85, 144402 (2012).

- Hu and Ding [2012] J. Hu and H. Ding, Local antiferromagnetic exchange and collaborative fermi surface as key ingredients of high temperature superconductors, Sci. Rep. 2, 381 (2012).

- Hu et al. [2015] J. Hu, C. Le, and X. Wu, Predicting unconventional high-temperature superconductors in trigonal bipyramidal coordinations, Phys. Rev. X 5, 041012 (2015).

- Richard et al. [2017] P. Richard, A. van Roekeghem, B. Q. Lv, T. Qian, T. K. Kim, M. Hoesch, J.-P. Hu, A. S. Sefat, S. Biermann, and H. Ding, Is symmetrical to with respect to half shell filling?, Phys. Rev. B 95, 184516 (2017).