A two-component model of hadron production applied to spectra

from 5 TeV and 13 TeV - collisions at the large hadron collider

Abstract

The ALICE collaboration at the large hadron collider (LHC) recently reported high-statistics spectrum data from 5 TeV and 13 TeV - collisions. Particle data for each energy were partitioned into event classes based on the total yields within two disjoint pseudorapidity intervals denoted by acronyms V0M and SPD. For each energy the spectra resulting from the two selection methods were then compared to a minimum-bias INEL average over the entire event population. The nominal goal was determination of the role of jets in high-multiplicity - collisions and especially the jet contribution to the low- parts of spectra. A related motivation was response to recent claims of “collective” behavior and other nominal indicators of quark-gluon plasma (QGP) formation in small collision systems. In the present study a two-component (soft + hard) model (TCM) of hadron production in - collisions is applied to the ALICE spectrum data. As in previous TCM studies of a variety of A-B collision systems the jet and nonjet contributions to - spectra are accurately separated over the entire acceptance. Distinction is maintained among spectrum normalizations, jet contributions to spectra and systematic biases resulting from V0M and SPD event selection. The statistical significance of data-model differences is established. The effect of spherocity (azimuthal asymmetry measure nominally sensitive to jet production) on ensemble-mean vs event multiplicity is investigated and found to have little relation to jet production. The general results of the TCM analysis are as expected from a conventional QCD description of jet production in - collisions.

pacs:

12.38.Qk, 13.87.Fh, 25.75.Ag, 25.75.Bh, 25.75.Ld, 25.75.NqI Introduction

Claims of quark-gluon plasma (QGP) formation in Au-Au collisions at the relativistic heavy ion collider (RHIC) and subsequently in Pb-Pb collisions at the large hadron collider (LHC) were based on certain data features initially seen as unique to more-central A-A collisions and not appearing in small asymmetric A-B control systems such as -Au or -Pb where QCD theory suggested that QGP formation should be unlikely. However, in recent years similar features have been observed in LHC data for -Pb collisions and high-charge-multiplicity - collisions and have been interpreted as evidence for QGP formation in small collision systems ppcms ; dusling . But the recent LHC results could also be interpreted to indicate that data features conventionally associated with QGP formation may result from unexceptional QCD processes.

The ALICE collaboration recently published a comprehensive high-statistics study of spectra from 5 TeV and 13 TeV - collisions alicenewspec . The analysis employs two methods to sort collision events into ten multiplicity classes each and application of spherocity , a measure of the azimuthal nonuniformity of distributed , to estimate the “jettiness” of events. Several methods are applied to determine variation of spectrum shape with charge multiplicity, event-selection method and spherocity.

The study reported in Ref. alicenewspec is motivated in part by claimed observation in - and -Pb collisions of evidence for radial and elliptic flow (“collectivity”) aliflows1 ; aliflows2 as well as strangeness enhancement alistrange similar to that observed in more-central - collisions and attributed there to QGP formation. Observation of such effects in low-density systems occupying small space-time volumes runs counter to initial theoretical expectations concerning QGP formation. The study seeks to understand hadron production associated with jets in relation to soft particle production: “The aim of this study is to investigate the importance of jets in high-multiplicity pp collisions and their contribution to charged-particle production at low .”

The phenomenology of high-energy - collision data serves as an essential reference for high-energy - and - collisions, specifically regarding claims of novel physical mechanisms such as QGP formation perfect or possible manifestations of hydrodynamic flows even in small collision systems ppflow ; moreppflow . One can formulate a set of critical questions addressed to available - data: (a) What is the evidence for or against azimuthally symmetric radial flow, and for or against elliptic flow and “higher harmonics” as manifestations of azimuthal asymmetry? (b) Are nominally flow-related azimuthal features certainly disjoint from jet production? (c) Are jet contributions to spectra significantly modified by a dense medium (i.e. QGP)? (d) Does the charge-multiplicity () dependence of certain data features reflect the onset of such a medium with increasing particle density? If the QGP scenario is valid then systematic behavior of various data features should be synchronized with emergence of a common underlying dense medium. Are comprehensive data trends consistent with such expected synchronization?

A two-component (soft + hard) model (TCM) of hadron production near mid-rapidity in A-B collisions was initially derived from the charge-multiplicity dependence of spectra from 200 GeV - collisions ppprd . The dependence of yields, spectra and two-particle correlations has played a key role in establishing (a) the nature of hadron production mechanisms in - collisions and (b) that the TCM hard component of spectra is quantitatively consistent with predictions based on event-wise reconstructed jets fragevo ; jetspec ; jetspec2 . The question of recently-claimed collectivity or flows in small (- and -) systems has been addressed in terms of the resolved TCM soft and hard components and evidence (or not) for radial flow in differential studies of spectra hardspec ; ppquad ; ppbpid .

Reference alicetomspec reported previous TCM analysis of 13 TeV - spectra that serves as a precursor to the present study (see App. A). Then-available spectrum data alicespec were presented only as ratios to minimum-bias spectra and only for a limited range. The present study extends those results utilizing both 5 TeV and 13 TeV data. Spectra for the two energies and for two methods of event selection, V0M and SPD, are decomposed into soft and hard components for ten event multiplicity classes each. Spectrum biases resulting from event selection methods are evaluated and compared. The quality of the TCM description is determined via data-model differences (not ratios) compared to statistical uncertainties (Z-scores) as a significance test. A TCM for ensemble-mean or is defined and applied to vs data from Ref. alicenewspec . Evolution of the () trend with spherocity is examined in detail – especially the relation of to dijet production. An ironic result emerges.

The TCM serves as an accurate reference for A-B collision systems that is not derived from fits to individual spectra. The TCM is required to describe diverse data formats applied to a broad array of collision systems self-consistently. It precisely separates jet and nonjet data contributions, greatly facilitating and simplifying data interpretation. Data-TCM deviations may reveal systematic data biases as in the present study or identify new physics beyond conventional models as in Ref. ppquad .

This article is arranged as follows: Section II summarizes - spectrum data, methods and conclusions reported in Ref. alicenewspec . Section III describes the TCM for - spectra. Section IV summarizes selection biases resulting from two event-selection criteria and their evolution with event multiplicity . Section V reviews some spectrum shape measures. Section VI describes the TCM for ensemble and reviews results from Ref. alicenewspec for evolution of () trends with varying spherocity . Section VII discusses systematic uncertainties. Sections VIII and IX present discussion and summary.

II 5 and 13 TV - spectrum data

Reference alicenewspec reports spectra from 5 and 13 TeV - collisions for two event selection methods (V0M and SPD) and for ten charge-multiplicity classes each. For each energy the same minimum-bias (INEL ) event ensemble is effectively sorted into multiplicity classes in two ways. The acceptance is GeV/c. The angular acceptance is on azimuth and on pseudorapidity. The total event numbers are 105 and 60 million for 5 and 13 TeV respectively. The basic spectra are further analyzed via several methods. As noted, the stated main goal of the study is to understand the role of jets in high-multiplicity - collisions.

II.1 Motivation and strategy

The context presented for the spectrum analysis reported in Ref. alicenewspec is claimed observation at the LHC of collectivity – i.e. radial aliflows1 ; aliceppbpid and anisotropic (e.g. elliptic, higher harmonic) aliflows2 flows – and strangeness enhancement alistrange in - and -Pb collisions whereas those phenomena had been designated as indicators of QGP formation only in high-density - collision systems. A variety of models based on hydrodynamics, string percolation, multiparton interactions or fragmentation of saturated gluon states are “…able to describe…qualitatively well…some features of data.” However, concerns have been expressed about interpretations of data from small collision systems in terms of QGP formation without a more-rigorous examination of data and models thoughts .

It is asserted that a spectrum “carries information of the dynamics of soft and hard interactions.” Reference is made to three intervals: GeV/c is said to be “quantitatively well described by perturbative QCD (pQCD) calculations.”111A pQCD (i.e. jet) description is quantitatively consistent with the - spectrum hard component down to 0.5 GeV/c fragevo . Below that limit one must “resort to phenomenological QCD inspired models [i.e. Monte Carlo models].” Novel effects claimed for - and -Pb collisions are said to appear in GeV/c and GeV/c. Reference alicenewspec asserts that “The present paper reports a novel multi-differential analysis aimed at understanding charged-particle production associated to partonic scatterings with large momentum transfer and their possible correlations with soft particle production.” In essence, Ref. alicenewspec poses the question: what is the jet contribution to hadron spectra at low ?

II.2 - spectrum data

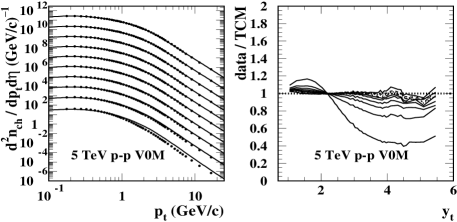

Figures 1 and 2 show spectra (points) for 5 TeV and 13 TeV respectively. Panels (a) and (c) show spectra for sorting criteria V0M and SPD respectively multiplied by successive powers of ten from lowest to highest multiplicity in a conventional log-log plot format. The solid curves represent the TCM described in Sec. III. The TCM is not derived from fits to individual spectra. Panels (b) and (d) show data/model ratios based on the TCM. Line types for the four highest- classes vary as solid, dashed, dotted and dash-dotted. That convention is applied consistently in what follows unless explicitly noted. In those ratios certain “noise” components appear as common to multiple spectra. It is possible that those features arise from efficiency corrections generated by a Monte Carlo simulation with a more-limited number of events. Power-law fits to spectra above 6 GeV/c are used to infer a power-law exponent which is observed to decrease in magnitude with increasing (but see Sec. V.1). Note that spectra as plotted in Ref. alicenewspec and Figs. 1 and 2 (a,c) below are in the form whereas corresponding to as defined in Eq. (III.1) includes an additional factor in its denominator.

II.3 Ensemble-mean vs and spherocity

Spectra are also sorted according to spherocity or [see Eq. (14)], said to be a measure of the “jettiness” of the event-wise azimuth distribution, where or 100% is associated with near-isotropic events. For ten classes of spherocity ensemble-mean vs multiplicity trends for 13 TeV data are evaluated. Event multiplicity classes are defined within (i.e. SPD selection). Reference alicenewspec states: “Since the goal of the present study is to separate jet events from isotropic ones, we study different spherocity classes for a given multiplicity value.” “…the most jet-like and [most] isotropic events will be referred to as 0-10% and 90-100% spherocity classes, respectively.”

II.4 Summary and conclusions

The abstract of Ref. alicenewspec asserts that spectra exhibit little energy dependence (between 5 and 13 TeV), and the high- tails of spectra increase faster than linearly with event multiplicity . Regarding the spherocity study “For low- (high-) spherocity events, corresponding to jet-like (isotropic) events, the average is higher (smaller) than that measured in INEL pp collisions.”

Although it is reported that ensemble-mean increases with decreasing spherocity (expected to indicate increased jettiness) the observed shape of vs doesn’t change significantly with spherocity (contradicting the expectation, see Sec. VI.3). Spherocity results are said to “illustrate the difficulties for the [Monte Carlo] models to describe different observables once they are differentially analyzed as a function of several variables.”

The summary states that “For a fixed center-of-mass energy, particle production above GeV/c exhibits a remarkable multiplicity dependence. Namely, for transverse momenta below 0.5 GeV/c, the ratio of the multiplicity dependent spectra to those for INEL pp collisions is rather constant, and for higher momenta, it shows a significant dependence. The behavior observed for each of the two multiplicity estimators are consistent within the interval defined by the V0M multiplicity estimator, which gives a reach of . For the highest V0M multiplicity class, the ratio increases going from GeV/c up to GeV/c, then for higher , it shows a smaller increase.” Those qualitative observations contrast with highly differential and quantitative TCM results from the present study as presented below in Secs. III - VI.

III - spectrum TCM

The spectrum TCM, first reported for 200 GeV - collisions in Ref. ppprd , is basically consistent with the TCM first reported in Ref. pancheri in response to UA1 “minijets” from the CERN SS. The TCM provides an accurate description of yields, spectra and two-particle correlations for A-B collision systems based on linear superposition of - or parton-parton collisions. In general, the TCM serves as a predictive reference for any collision system. Deviations from the TCM then provide systematic and quantitative information on details of collision mechanisms. In this section the spectrum TCM is reviewed and then applied to 5 TeV and 13 TeV spectra for two event selection methods from Ref. alicenewspec .

III.1 spectrum TCM for unidentified hadrons

The or spectrum TCM is by definition the sum of soft and hard components with details inferred from data (e.g. Ref. ppprd ). For - collisions

where is an event-class index and factorization of the dependences on and is a central feature of the spectrum TCM inferred from 200 GeV - spectrum data in Ref. ppprd . The motivation for transverse rapidity (applied to hadron species ) is explained in Sec. III.2. The integral of Eq. (III.1) is , a sum of soft and hard charge densities. and are unit-normal model functions independent of . The centrally-important relation with is inferred from - spectrum data ppprd ; ppquad ; alicetomspec . is then obtained from measured as the root of the quadratic equation with determined by an energy trend derived from - spectrum data covering a large energy interval alicetomspec . It is important to distinguish TCM model elements from spectrum data soft and hard components. It is useful to recall that values 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 are approximately equivalent to values 0.15, 0.5, 1.4, 3.8 and 10 GeV/c.

III.2 spectrum TCM model functions

The - spectrum soft component is most efficiently described on transverse mass whereas the spectrum hard component is most efficiently described on transverse rapidity . The spectrum TCM thus requires a heterogeneous set of variables for its simplest definition. The components can be easily transformed from one variable to the other by Jacobian factors defined below.

Given spectrum data in the form of Eq. (III.1) the unit-normal spectrum soft-component model is defined as the asymptotic limit of data spectra normalized in the form as goes to zero. Hard components of data spectra are then defined as complementary to soft components, with the explicit form

| (2) |

directly comparable with TCM model function .

The data soft component for a specific hadron species is typically well described by a Lévy distribution on . The unit-integral soft-component model is

| (3) |

where is the transverse mass-energy for hadron species with mass , is the Lévy exponent, is the slope parameter and coefficient is determined by the unit-normal condition. Model parameters for several species of identified hadrons have been inferred from 5 TeV -Pb spectrum data as described in Ref. ppbpid . A soft-component model function for unidentified hadrons can be defined as the weighted sum

| (4) |

where the weights for charged hadrons follow . In the present context model function should not be confused with spherocity introduced in Ref. alicenewspec .

The unit-normal hard-component model is a Gaussian on (as explained below) with exponential (on ) or power-law (on ) tail for larger

where the transition from Gaussian to exponential on is determined by slope matching fragevo . The tail density on varies approximately as power law . Coefficient is determined by the unit-normal condition. Model parameters are derived as described in App. A except as noted in the main text.

All spectra are plotted vs pion rapidity with pion mass assumed. The motivation is comparison of spectrum hard components demonstrated to arise from a common underlying jet spectrum on fragevo , in which case serves simply as a logarithmic measure of hadron with well-defined zero. in Eq. (4) is transformed to via the Jacobian factor to form for unidentified hadrons. in Eq. (III.2) is always defined on as noted. In general, plotting spectra on a logarithmic rapidity variable provides improved access to important spectrum structure in the low- interval where the majority of jet fragments appear.

III.3 - spectrum data

Figures 1 and 2 (a,c) show the general relation between the TCM (solid) and ALICE data (points). The TCM is not the result of fits to individual spectra. The curves actually represent predictions derived from a self-consistent description of - spectra covering the energy interval 17 GeV to 13 TeV (Ref. alicetomspec and App. A). The data/TCM ratios in (b,d) provide important information on biases resulting from V0M and SPD event sorting methods.

The TCM format of Figs. 3 and 4 then provides a more-differential decomposition of spectrum data into soft and hard components. Panels (a,c) show full data spectra (thin solid) in the normalized form defined above that are directly comparable with soft-component model (bold dashed). Below 0.5 GeV/c () the data curves closely follow the model. The same model is used for both event-selection methods.

Panels (b,d) show inferred data hard components defined by Eq. (2) (thin, several line styles) compared to TCM hard-component model (bold dashed). Deviations from below appear in every - collision system (e.g. 200 GeV as reported in Ref. ppprd ). The horizontal dotted lines provide a check on proper normalization of hard-component model The data hard component for the lowest multiplicity class is not shown because there is in effect very little jet contribution to those events due to strong selection bias. Note that full spectra in panels (a,c) for the lowest class are approximately consistent with . The same model is used for both event-selection methods.

Although Ref. alicenewspec states that - spectra show “little energy dependence” both soft and hard components exhibit significant energy dependence as previously reported in Ref. alicetomspec . The TCM parameters (soft-component exponent) and (hard-component exponent) vary systematically with . The variation is apparent as shifts of and intercepts on (at plot lower bounds) to larger values with increasing energy. The former may be related to increasing depth of the longitudinal splitting cascade on proton momentum fraction with increasing energy alicetomspec , and the latter is certainly related to expected evolution of the underlying jet spectrum with increasing - collision energy jetspec2 .

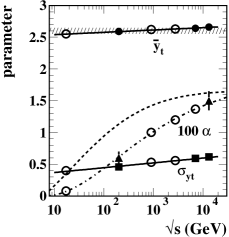

III.4 Spectrum TCM parameter summary

Table 1 presents TCM parameters for 5 TeV and 13 TeV - collisions. Entries are grouped as soft-component parameters , hard-component parameters , hard/soft ratio parameter and NSD (non-single-diffractive) soft density . For unidentified hadrons soft component may be approximated by Eq.(3) for pions only with parameters as in Table 1. Slope parameter MeV is held fixed for all cases consistent with data. Its value is determined within a low- interval where the hard component is negligible. For the present analysis Eq. (3) was evaluated separately for pions, kaons and protons with , 200 and 210 MeV respectively. Those expressions were then combined to form via Eq. (4) with , 0.12 and 0.06 respectively. For each energy the same exponent was applied to three hadron species. Lévy exponent values and hard-component values are as reported in Table 1.

values are derived from the universal NSD trend inferred from spectrum and yield data. values are derived from the TCM relation . The NSD values can be compared with and 7.60 for 5 and 13 TeV INEL events from Ref. alicenewspec [above its Eq. (1)]. The 13 TeV number contrasts with in its Fig. 5 (center panel). Appendix A describes previous TCM analysis of 13 TeV - spectrum data from Ref. alicespec .

| (TeV) | T(̇MeV) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.0 | 145 | 8.5 | 2.63 | 0.58 | 4.0 | 1.45 | 5.0 | 5.3 |

| 13.0 | 145 | 7.8 | 2.66 | 0.60 | 3.8 | 1.70 | 5.8 | 6.3 |

It should be noted that the values for 5 TeV and 13 TeV in Table 1 are 0.0145 and 0.0170 whereas Table 2 includes values reported in Ref. alicetomspec for alpha as 0.013 and 0.015. The earlier values were based on limited 13 TeV - spectrum data from Ref. alicespec . The updated values better accommodate the much more complete spectrum data reported in Ref. alicenewspec . The % increase in values is compatible with estimated uncertainties in Fig. 16 (left) of Ref. alicetomspec but also favors a prediction of the trend based on measured - jet cross sections and fragmentation functions (dashed curve in that panel).

IV spectrum biases and evolution

V0M and SPD event-selection methods bias event structure (e.g. spectra) in different ways. Biases are examined here relative to a TCM reference. The TCM for - collisions assumes linear superposition of parton-parton interactions consistent with basic QCD (e.g. published jet measurements). The TCM is not fitted to individual spectra; it serves as a fixed reference for comparison of biases from different event-selection methods.

IV.1 Spectrum ratios vs

In its Figs. 2 and 3 Ref. alicenewspec presents ratios of spectra for ten classes to those for minimum-bias INEL ensemble averages for each of two event selection criteria. It is noted that “While at low ( GeV/c) the ratios exhibit a modest dependence, for GeV/c they strongly depend on multiplicity and .” It is possible to arrive at more-detailed quantitative conclusions using TCM-based techniques first reported in Ref. ppprd .

Figure 5 shows spectra from 13 TeV - collisions for V0M (left) and SPD (right) event classes and for data from Ref. alicenewspec (solid) and corresponding TCM (dashed). The various spectra are in ratio to the TCM spectra for class 5 where 1-10 goes from higher to lower . The spectra have first been normalized by the corresponding soft-component density as they appear in Fig. 4 (a,c).

The corresponding Figs. 2 and 3 in Ref. alicenewspec show ratios of spectra to a single minimum-bias INEL reference spectrum. As such the spectrum ratios include three sources of systematic variation: (a) mean event multiplicity varying from class to class, (b) varying jet contribution relative to charge multiplicity and (c) bias effects that are of major interest. It is then essentially impossible to sort out what cause produces which effect.

Figure 5 removes variation due to mean event multiplicity, but strong variation of jet contributions relative to total yield is still confused with bias effects. As a consequence of that plotting format, below = 2 (0.5 GeV/c) spectra nearly coincide as a result of the chosen normalization and are nearly constant on , qualitatively consistent with the observation in Ref. alicenewspec (modulo distortions from selection bias discussed in the next subsection). Above that point the ratios vary strongly with and , also qualitatively consistent with Ref. alicenewspec . However, such variation is to be expected given that jet production varies approximately quadratically with .

Close examination of the left panel reveals that the data spectrum for the highest V0M class corresponds to the TCM (dashed) within statistics. Then with decreasing spectra are suppressed relative to the TCM at higher but are enhanced at lower , the enhancement mode moving to lower . Correlated suppression and enhancement lead to trends in Fig. 12 where spectrum integrals adhere to the TCM trend for all event classes even as the spectrum hard components are significantly modified in shape with decreasing .

IV.2 V0M and SPD biases relative to the TCM

Event sorting or selection in Ref. alicenewspec is based on different angular acceptances denoted by acronym. SPD denotes tracklets (two hits plus vertex) within , the same angular acceptance as for the spectra. V0M denotes a “forward estimator” with combined acceptances and that is said to “minimize the possible autocorrelations introduced by the use of the mid-pseudorapidity estimator.” The term “autocorrelations” is here misused. The autocorrelation function (special case of cross-correlation function) is an established statistical method for analyzing time series autocorr . A better term is selection bias wherein event selection is based on the same particle sample (e.g. mid-rapidity hadrons) as the object of study (mid-rapidity spectra).

Figure 6 shows data/TCM ratios for 13 TeV - collisions and for V0M (left) and SPD (right) event classes. In contrast to Fig. 5 the systematic variation of jet yield relative to total yield is largely canceled in the data/TCM ratio. The same TCM reference is used for both selection methods. What remains is the bias effects of interest. The 5 TeV results are similar. The two methods bias spectra substantially but in apparently different ways. V0M for smaller multiplicities suppresses spectra at higher but produces complementary enhancement at lower . SPD for smaller multiplicities also suppresses higher and enhances lower , but for greater there is apparently strong enhancement for higher whereas V0M produces no significant corresponding effect. However, spectrum ratios exaggerate structure at higher while concealing important structure at lower alicetomspec . For example, compare these results with data-model differences in ratio to statistical errors (Z-scores) in Fig. 8.

As can be seen in Figs. 3 and 4 (b,d) the physical process biased by event selection is jet production represented by the TCM spectrum hard component. The TCM hard-component reference has fixed exponent corresponding to power-law exponent . The constant trend for the data/TCM ratio above = 4 in Fig. 6 (left) is consistent with or independent of , whereas the result in Fig. 6 (right) is consistent with strong decrease of those parameters with increasing . See Figs. 9 (right) and 17 (left). The different forms of spectrum bias relating to V0M and SPD as indicated by Fig. 6 can thus be understood in terms of jet production.

Minimum-bias jet production near midrapidity arises from three processes: (a) separate parton splitting cascades within projectile protons resulting from inelastic scattering, (b) occasional large-angle scattering of cascade (participant) partons and (c) fragmentation of scattered participant partons to dijets. A proton splitting cascade (event-wise parton distribution function or PDF) is sensitive to initial conditions and fluctuates strongly from event to event gosta . Likewise, the fragment distribution within a jet (also a splitting cascade) fluctuates strongly from jet to jet. The biases indicated in Fig. 6 result from sorting the same minimum-bias INEL event population according to two different criteria.

Since V0M selection is derived from particle yields at higher outside the acceptance for spectra it cannot significantly bias the jet formation process itself since most jets, near the lower bound of the jet spectrum, are derived from low- partons appearing near midrapidity within a longitudinal cascade. However, V0M selection for low may influence the underlying jet spectrum resulting from the event-wise PDF, i.e. softening the jet spectrum. The result is a shift of the data hard component to lower without changing its shape, consistent with Fig. 6 (left).

Since SPD selection is based on particle yields within the same acceptance as for spectra it relates primarily to low- partons and low-energy jets. It cannot significantly bias the event-wise PDF at larger (or ) but can strongly bias the parton scattering and fragmentation process near midrapidity. Figure 6 (right) suggests that whereas lower SPD values produce a bias similar to V0M (softened jet spectrum), for higher SPD values the effective jet spectrum and mean fragmentation function are biased to harder distributions leading to evolution of the hard-component tail. The manifestation in the data/TCM ratio seems dramatic but a very small fraction of all particles is actually involved. Figures 3, 4 and 8 provide a more transparent picture of hard-component biases arising from V0M and SPD event selection.

The role of fluctuations warrants further consideration. It would be informative to have a 2D plot of event density on SPD vs V0M. Given the jet production scenario described above one may conjecture qualitatively that for large V0M yields (and hence event-wise PDF) the SPD event multiplicity and especially jet contribution is free to fluctuate strongly over a large range whereas the multiplicity mean value for fixed V0M remains modest as observed. In contrast, for large SPD yields the largest jet fluctuations are singled out, V0M is pinned to its highest value (V0M fluctuations are thus limited) and the multiplicity mean value for fixed SPD is large as observed. In Fig. 8 the most significant bias structure (the bipolar excursion on ) has maximum amplitude for the lowest values of V0M and SPD. The trend is consistent with a biased underlying jet spectrum (via the event-wise PDF).

IV.3 Significance of data-model differences

Data/model spectrum ratios may exaggerate deviations at higher compared to deviations at lower . A more transparent representation is based on statistical-significance measures. The Z-score zscore compares data-model differences to their statistical uncertainties

| (6) |

where is an observation (e.g. spectrum data), is an expectation (e.g. predictions derived from a model) and is the statistical uncertainty of the observation.

Figure 7 shows statistical errors (solid) accompanying published VOM and SPD spectrum data for 5 and 13 TeV - collisions which exhibit step-like structures. If used to process data within ratios those structures are injected into the result. Smooth approximations (dashed) are introduced to represent statistical errors without step-like structures. The approximated error curves are used for data-model comparisons below.

Figure 8 shows data-TCM differences in ratio to statistical uncertainties for 5 TeV (left) and 13 TeV (right) - collisions and for V0M (upper) and SPD (lower) event selection. Such Z-score results can be contrasted with data/TCM ratios as in Fig. 6. Whereas in the ratio format biases for V0M and SPD appear quite different, the Z-scores in Fig. 8 reveal the statistical significance of data-model deviations. Despite noticeable differences at higher the most significant bias effects are similar. The bias amplitude in terms of Z-scores seems to track with fraction of total cross section rather than with .

V spectrum shape measures

Reference alicenewspec analyzed the evolution of spectrum shapes with varying charge multiplicity in two ways: (a) power-law model fits to spectra to infer trends for power-law exponent and (b) variation of integrated yields within three intervals compared to a minimum-bias reference as a function of . This section considers such shape-measure results in the context of the TCM.

V.1 Power-law fits to high- intervals

Reference alicenewspec fitted a power-law function to 13 TeV - spectra above 6 GeV/c () to estimate exponents vs for V0M and SPD events. A related result can be obtained without curve fitting via a logarithmic derivative applied directly to data hard components as in Figs. 3 and 4 (b,d) or :

| (7) | |||

If [high- tail of ] then . is a rough estimate, but is established by direct comparison of results from Eq. (7) (upper and lower) for the same spectra. Power-law exponent invoked by Ref. alicenewspec should not be confused with TCM Lévy exponent for soft component .

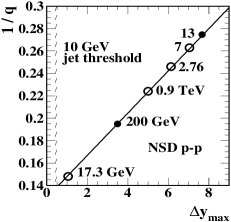

Figure 9 (left) shows logarithmic derivatives vs (thin solid) for eight classes of 13 TeV V0M - collisions. The bold dashed curve results from applying the same technique to TCM hard-component model . Horizontal dotted lines represent values expected for 5 (upper) and 13 (lower) TeV - collisions from TCM energy trends related to Ref. alicetomspec (see Table 1). The crossed solid lines for and remind that while the mode of the hard component on is near 2.65 (where the upper line of Eq. (7) would pass through zero) the mode on is near GeV/c ( where the lower line of Eq. (7) would pass through zero). See Fig. 20 (right) and associated text.

In this data format the spike artifacts common to all spectrum classes are most evident since differential measures are sensitive to short-wavelength structure. As noted, it may be that those artifacts arise from efficiency corrections derived from Monte Carlo data with more-limited statistics than the spectrum data themselves.

Figure 9 (right) shows exponents vs for three spectrum data types. The values are in each case averages over the ten highest- data points ( or GeV/c) in the left panel. That limit is lower than the fit interval GeV/c applied in Ref. alicenewspec . However, the V0M results in the left panel indicate that the exponent trend is approximately constant down to , and the added points provide more-stable values. The values for highest and lowest multiplicity classes are not plotted because of excessive noise in the log-derivative results. The V0M data trends on are approximately constant, with values close to 5.60 (13 TeV) and 5.80 (5 TeV). The dotted lines correspond to TCM 3.8 for 13 TeV and 4.0 for 5 TeV related to Ref. alicetomspec (see Table 1). The SPD data trend varies strongly, decreasing (i.e. to harder spectra) with increasing . Those trends are consistent with spectrum data trends in Figs. 1 and 2 (b,d) showing deviations from fixed TCM references. The solid curve for 13 TeV SPD data is derived from Eq. (17) with . The 5 TeV SPD data are more scattered than other data trends and are thus omitted to improve visual access to the 13 TeV SPD trend relevant to Fig. 5 of Ref. alicenewspec .

In its summary Ref. alicenewspec concludes “…within uncertainties, the functional form of as a function of is the same for the two multiplicity estimators [V0M and SPD] used in this analysis. Moreover, is found to decrease with .” The results in Fig. 9 contradict that conclusion: The power-law trend is dramatically different for V0M and SPD, and does not decrease with charge density for V0M event selection. The contrast between V0M and SPD event selection is most evident in Fig. 6. In the left panel the effective exponent at high relative to the fixed TCM value is itself fixed (the ratio is approximately constant above = 4). The right panel shows dramatic variation of the effective SPD exponent from high (soft) to low (hard) with increasing .

V.2 Spectrum response to selection bias

Figures 4 and 6 of Ref. alicenewspec deal with other manifestations of selection bias in spectrum structure. Figure 6 compares yields integrated within three specific intervals for ten multiplicity classes in ratio to yields in the same intervals from the INEL minimum-bias class. The resulting data trends are compared to a linear trend corresponding to no change in spectrum shape with . Figure 4 compares V0M and SPD spectra for nearly-equal charge densities . Ratio SPD/V0M drops to 0.85 near 4 GeV/c for both 5 and 13 TeV spectra. What follows is an effort to understand systematics details and provide a physical interpretation.

Figure 10 (left) shows integrated yields for three intervals from spectra for ten classes of SPD and V0M events in ratio to yields in the same intervals (points) from a 13 TeV TCM spectrum defined on data values with as for INEL events in Ref. alicenewspec . The solid lines are TCM references resulting from the same method applied to TCM spectra defined “on a continuum” (i.e. on 100 equal-spaced points extending down to = 0). Soft and hard TCM model functions do not vary with . The different slopes of the TCM lines result only from the different fractions of soft and hard components in each interval. The log-log plot format ensures that suppression at smaller is as visible as enhancement at larger . The effects of selection bias are indicated by deviations of data from the TCM trends, not from the dotted line (that assumes no change in jet production). As for Fig. 5 above or Figs. 2 and 3 in Ref. alicenewspec distinction should be maintained between variations due to generic jet trends and bias effects relative to those variations.

Several features are apparent. For V0M events points for different at higher approximately coincide, consistent with Fig. 6 (left) where the ratios for higher are nearly flat on . In contrast, higher- points for SPD vary strongly with interval , consistent with Fig. 6 (right). For lowest classes there is strong suppression below the TCM references for both V0M and SPD, also consistent with spectrum ratios in Fig. 6, but suppression for V0M is significantly greater than for SPD.

Figure 10 (right) shows 13 TeV data/TCM spectrum ratios (dashed) for class II V0M/TCM and class VII SPD/TCM, data/data ratio SPD/V0M (solid) that appears in Fig. 4 of Ref. alicenewspec and the corresponding ratio of TCM spectra (dash-dotted). Commenting on the SPD/V0M spectrum ratio in its Fig. 4 (identical to the solid curve here) Ref. alicenewspec states that “For transverse momenta within 0.5-3 GeV/c the spectra [sic] for the [V0M] multiplicity class II is harder than that for the [SPD] multiplicity class VII′.” However, the 5% difference in for V0M (20.5) and SPD (19.5) plays a significant role as indicated by the TCM ratio (dash-dotted). Since TCM model functions and are fixed, charge density determines the TCM spectrum shape. The TCM ratio demonstrates the effect of the V0M vs SPD multiplicity difference: at least half of the SPD/V0M ratio deviation from unity arises from the difference in . Absent detailed comparisons with a model the term “harder” may mean a modified jet fragment distribution or simply more or less jet production according to .

One should also note that class VII is comparatively low for SPD whereas class II is relatively high for V0M. Given the trends in Fig. 8 (b,d) one should then expect a substantial difference in bias for the two cases, as observed. Concerning the short-wavelength structure, the peaks near 5 GeV/c in the data/TCM ratios certainly correspond to the bipolar structure near in Fig. 9 (left) that is common to all classes and therefore most probably results from the inefficiency correction. That structure then cancels in the SPD/V0M data ratio even though the spectra are from quite different event classes.

V.3 Spectrum running integrals

In Sec. IV of Ref. ppprd running integrals of spectra were the basis for discovery of the two-component structure of 200 GeV - spectra without a priori assumptions. It was observed that spectra normalized not with total charge density but with a “soft component” defined as the root of with coincided below ( GeV/c) within data uncertainties and that the endpoints of spectrum running integrals also followed a trend consistent with the above quadratic equation. The same approach is applied here to 13 TeV - spectrum data. One purpose is demonstration that the spectrum TCM is required by - data for any energy, is not imposed a priori.

Figure 11 shows running integrals of spectra for ten classes of 13 TeV - collisions each for V0M (left) and SPD (right) event selection criteria derived from data (solid) and TCM (dashed) spectra. Spectra are normalized by inferred from reported in Ref. alicenewspec using the quadratic equation defined above with for 13 TeV, 12% higher than reported in Ref. alicetomspec . The uncorrected spectrum running integrals are then defined as

| (8) |

Note that a factor in the integrand is required in order to be consistent with the definition of in Eq. (III.1). Running integrals on data values within the ALICE acceptance can be simply corrected for incomplete acceptance. The correction is addition of estimated corresponding to GeV/c (see Fig. 14, left and related text).

The corrected data running integrals can be expressed in TCM form on as

| (9) |

As in Ref. ppprd the corrected data running integrals coincide below ( GeV/c) within data uncertainties then separate and achieve saturation above ( GeV/c). Running integral (bold dotted) of TCM soft component is defined as the limit of data running integrals as where . The functional form of given by Eqs. (3) and (4) is then observed to generate the required limiting form of within data uncertainties. saturates at 1 by definition. The same form is used for V0M and SPD data.

The data trends in Fig. 11 demonstrate the following: (a) The shape of data soft component does not vary significantly with , is consistent with . (b) The complementary data hard components are consistent with an erf function as running integral, demonstrating that data spectrum hard components are similarly-shaped peaked distributions with mode near = 2.7 ( GeV/c) as demonstrated in Ref. ppprd . It is then of interest to examine the trend of the data running-integral endpoints for TCM consistency.

Figure 12 shows running-integral endpoints vs for 5 TeV (left) and 13 TeV (right) derived from data spectra for V0M (solid dots) and SPD (open circles) event selection. The result for uncorrected spectra is . The inefficiency correction is then for the TCM defined on SPD values (dashed lines) as noted.

Those results demonstrate experimentally the precise quadratic relation between hard and soft data components: (a) All spectra coincide precisely for GeV/c given normalization via as computed from measured and (b) corrected-running-integral endpoints fall along straight-line loci (dotted lines) with . The endpoint trends in turn accurately indicate the fractional contribution of jet fragments to total spectra. For the highest multiplicity classes and 33% of hadrons are jet fragments.

In terms of TCM model functions, spectrum data demonstrate that one spectrum component scales linearly with at lower and that a second component scales quadratically with at higher . The structures of the data components vary little with . Running integrals provide a less-sensitive way to probe spectrum details compared to Figs. 3 and 4. However, there are no assumptions about spectrum structure, per Ref. ppprd . It is notable that the straight-line trends in Fig. 12 are followed down to the lowest event multiplicities although the data hard components are substantially biased there. The present study demonstrates that the spectrum TCM, with its quadratic relation between soft and hard components, is necessary to describe 13 TeV spectra (modulo biases described and interpreted in Sec. IV).

VI - ensemble systematics

Ensemble-mean data are inferred from hadron spectra via integration. The values in Ref. alicenewspec are obtained by integrating over GeV/c. Accurate values corresponding to ideal spectrum data could be obtained by extrapolating data spectra with a reliable spectrum model. Values obtained with unextrapolated spectra may be strongly biased, and correct interpretation of biased experimental values may be difficult. This section demonstrates how to relate a TCM reference to biased values obtained from spectrum data. The resulting bias is here estimated and corrected.

Reference alicempt reported a comprehensive analysis of data vs event multiplicity for -, -Pb and Pb-Pb collision systems. The strong increase of with for - collisions was there interpreted in terms of color reconnection as modeled within the PYTHIA Monte Carlo. The data trends were said to “pose a challenge to most of the existing models.” A TCM analysis of the same data was presented in Ref. alicetommpt . The observed vs trends were found to be consistent with the jet (hard component) contribution to hadron production in all cases.

Reference alicenewspec introduces spherocity measure intended to select more- or less-“jetty” events according to its value. Variation of jet production in a given event sample is expected to bias the vs trend. It is noted that as decreases increases, possibly due to an increased jet contribution to spectra as anticipated. In addition to biases resulting from incomplete acceptance and from V0M and SPD event selection methods, biases from event selection via spherocity are considered.

VI.1 Ensemble TCM for - collisions

The TCM for ensemble-mean data from - collisions is summarized. It is assumed that due to incomplete acceptance (lower bound GeV/c) only a fraction of the spectrum soft component is accepted. It is also evident that for such a low cutoff value the entire spectrum hard component is accepted. The values obtained from TCM model functions as defined by Table 1 are as follows: For models defined on the continuum () the mean values are GeV/c and GeV/c. For models defined on spectrum data values the mean values are GeV/c (corresponding to ) and GeV/c.

The TCM for charge densities averaged over some angular acceptance (1.6 for as in Ref. alicenewspec ) is

where is the - ratio of hard-component to soft-component yields ppprd and is defined in Ref. alicetomspec . is an uncorrected charge density corresponding to incomplete acceptance with .

The TCM for extensive ensemble-mean total integrated within some angular acceptance and from - collisions for given can be expressed as

The conventional intensive ratio of extensive quantities

| (12) |

(assuming tommpt )222Because of the additional factor in the effect of the low- cutoff is minimal and . in effect partially cancels dijet manifestations represented by ratio that may be of considerable interest. The alternative ratio

preserves the simplicity of Eq. (VI.1) and provides a convenient basis for testing the TCM hypothesis precisely.

VI.2 Spherocity event selection

Reference alicenewspec studies ensemble trends vs spherocity

| (14) |

where is a unit vector varied to minimize . Limit 0% would result for a single vector. Limit 100% would result for an infinite number of vectors uniformly distributed on azimuth with equal magnitudes, in which case the quantity in parenthesis becomes = . Events are sorted into ten spherocity classes with the intent to identify events based on the particle fraction arising from jets, i.e. the event “jettiness.”

VI.3 ALICE ensemble results

Figure 13 (left) shows uncorrected (biased) ensemble values vs (thin solid) from 13 TeV - collisions for ten classes of spherocity . According to Ref. alicenewspec uncorrected is determined within acceptance GeV/c but is corrected by extrapolation to zero. The bold dash-dotted curve is a simple unweighted average of those spectra. As a result of the incomplete acceptance the values are biased upward as for in Eq. (12) with . The method of event selection on is based on appearing in angular acceptance (i.e. SPD). The solid dots and open circles are values obtained from TCM spectra defined on a “continuum” (100 points equally spaced on ) for V0M and SPD which are then unbiased (). The dashed curves are TCM trends for 5 and 13 TeV described by Eq. (12) with and hard component GeV/c fixed. The open squares are the TCM defined on SPD data values and integrated without extrapolation (i.e. are biased). The open triangles are from 13 TeV SPD spectra reported in Ref. alicenewspec also integrated without extrapolation (biased). The bias for uncorrected data is about 0.1 GeV/c (open squares vs upper dashed curve), consistent with Fig. 14 (left).

Figure 13 (right) shows the same data and curves (with the exception of spherocity-related curves, see Fig. 15) in the form of Eq. (VI.1). The TCM trends follow straight-line loci whose slopes are determined by the spectrum jet contribution, controlled in this case by parameter . The TCM defined on data points (open squares) and 13 TeV data SPD values (open triangles) have been corrected according to Eq. (VI.1) with in Eq. (VI.1) (see below). The dashed lines are Eq. (VI.1) with GeV/c and GeV/c as described in Sec. VI.1.

Figure 14 (left) shows the consequence of an incomplete acceptance for calculation of per Ref. tommpt . The solid curve is the running integral of that determines the inefficiency parameter as a function of spectrum lower bound , the fraction of that survives the cut. The lowest hatched band indicates soft component GeV/c determined from TCM fixed spectrum soft-component with no cutoff. (dashed) is the biased soft component resulting from the cutoff. For cutoff GeV/c in Ref. alicenewspec (as in the previous paragraph) and GeV/c, i.e. about 0.1 GeV/c higher than the unbiased value. The right panel is explained below.

Figure 15 (left) shows vs data trends in Fig. 13 (left) as they vary with spherocity (thin solid), the unweighted ensemble average (bold dash-dotted) and the TCM on 13 TeV SPD data values (open squares) transformed according to Eq. (VI.1) with that can be compared with Fig. 13 (right). The open triangles are 13 TeV SPD data values treated the same. In this plotting format it is evident that for most data spectra the primary variation with spherocity is soft-component mean (-axis intercepts in this plot) since the jet contribution (i.e. ), determining slopes in this format, shows little variation with . The upper dotted line is consistent with TCM GeV/c and GeV/c. The lower dotted line with GeV/c and is consistent with the lowest curve for .

Figure 14 (right) shows empirically-determined biased soft-component values for the individual trends in Fig. 15 (left). The estimated values are simply described by the power-law expression GeV/c (straight line) over the entire range. The hatched band denotes the unbiased soft-component mean GeV/c. The bias in this instance is not due to a cutoff (which has been corrected), is instead the result of the imposed condition. The two points above the hatched band thus do not “cause” the two elevated trends in Fig. 15 (right).

Figure 15 (right) shows inferred from data in the left panel via Eq. (VI.1) (second line) with taken from Fig. 14 (right) for each spherocity class. The value 1.39 GeV/c (hatched band) is just the corresponding to the 13 TeV TCM hard-component in Sec. III.2. The adopted criterion for determining values in Fig. 14 (right) is a requirement that trends be as level as possible above , consistent with a constant trend in Eq. (VI.1) reflecting the TCM. The horizontal dotted lines are the dotted lines at left transformed to obtain according to Eq. (VI.1).

Deviations from the TCM reference in Fig. 15 (right) could in general carry significant new information about collision dynamics. However, the data mainly indicate that while jet production increases about 30-fold over the interval it continues to follow the observed trend precisely no matter what the value of .

The comparison between V0M and SPD values indicates that the SPD hard component mean is biased down by almost 0.1 GeV/c independent of . The effect is evident in Fig. 6 in that the data trend on for higher and for V0M is flat (i.e. agreeing with the TCM) whereas for SPD the hard component is shifted down on (hence the tilt). Thus, for large SPD the high- tail is hardened while the main part of the hard component is softened. Trends for higher (thin solid) agree with the basic SPD data. Only the lowest two values show significant hardening of the hard component.

Information carried by spectra sorted by thus has three contributions: (a) bias of as in Fig. 14 (right) indicates bias of the spectrum soft component in response to imposition of an azimuthal (a)symmetry condition via , (b) bias of the spectrum hard component in the form of strong modification of the hard-component shape with low condition as in Fig. 8 resulting in lower independent of , and differently for V0M and SPD, and (c) minor modification of the jet contribution to varying with as in Fig. 15 (right). Note that for the SPD data used in the study the absolute jet production increases (relative to NSD - collisions) by 30-fold because of the variation (see Fig. 7 of Ref. alicenewspec ) while the largest effect of variation on the jet-related hard component is less than 10% (see Fig. 15, right).

VI.4 ALICE ensemble summary

Results in this section suggest several conclusions: (a) The basic -related data in Fig. 13 (left) (thin solid) are strongly biased by the incomplete acceptance (i.e. lower bound ). The TCM results in the same panel illustrate the consequence of determining by integration down to zero . In contrast, integrating TCM spectra on data values (open squares, with cutoff) is close to (but not equal to) integrating spectra from Ref. alicenewspec without extrapolation (open triangles).

(b) The bias can be removed via Eq. (VI.1) as shown in Fig. 13 (right). The biased TCM data in the left panel (open squares) are then in good agreement with unbiased TCM data in the right panel. The bias correction relies on estimating efficiency based on a TCM soft-component model that provides good data descriptions down to 0.15 GeV/c as demonstrated in Sec. III.3.

(c) The conventional ratio format of Eq. (12) and Fig. 13 (left) mixes two distinct physical mechanisms and is therefore difficult to interpret. Aside from bias corrections the data format corresponding to Eq. (VI.1) and Fig. 13 (right) provides a clear distinction between data soft and hard components, especially some differential features of the isolated jet contribution .

(d) Even with complete acceptance the data spectra from Ref. alicenewspec are still strongly biased by the event selection methods, both SPD and V0M, as illustrated by comparison with fixed (not fitted) TCM spectra in Sec. II.2 (ratios in right panels). With demand for lower , spectra for any are increasingly softened leading to decreased relative to the TMC trend in Fig. 13 (left) (compare open squares and open triangles) and Fig. 15 (left, note the strong drop-off near and below the NSD value). The effect is most apparent in Fig. 15 (right) because corresponds to slopes in the left panel.

(e) Event selection via spherocity was intended primarily to bias jet production alicenewspec . Data indicate that instead biases the spectrum soft component as evident from the nearly-linear trends in Fig. 15 (left) where the slopes (jet contribution) vary little while the -axis intercepts (soft component) vary strongly according to a simple power-law trend shown in Fig. 14 (right). The origin of the bias is simple to identify. Large values of favor uniform azimuth distributions of nearly-equal values. That condition then biases against higher- contributions to the soft component which reduces . Strong bias of would occur even in the absence of jets. The inferred soft-component power-law trend in Fig. 14 (right) is consistent for all values of . Figure 15 (right) shows that if bias of is corrected there is significant bias of beyond what is evident in Figs. 1 and 2 (b,d), but the bias magnitude is small compared to variation of jet production with .

(f) Just as for spectra, the TCM provides a basic reference for understanding ensemble-mean trends. The TCM is not fitted to individual data sets or collision systems. It is, in effect, a global representation of a large data volume including yields, spectra and two-particle correlations from multiple A-B collision systems over a broad range of collision energies. Deviations of properly-corrected particle data from the TCM then reveal differential details of the information carried by those data.

These conclusions can be compared with those reported in Ref. alicenewspec . In the introduction appears “The aim of this study is to investigate the importance of jets in high-multiplicity pp collisions and their contribution to charged-particle production at low .” The contribution of jets to hadron spectra at lower in - collisions has been established in a series of papers over fifteen years ppprd ; eeprd ; fragevo ; hardspec ; anomalous ; jetspec ; jetspec2 , none of which is cited in Ref. alicenewspec . The Ref. alicenewspec abstract states “Within uncertainties, the functional form of is not affected by the spherocity selection,” but that statement conflicts with actual data properties as revealed in Fig. 15 (right). bias relating to the jet contribution to spectra is small compared to that for soft component . Imposition of an condition on spectra does result in systematic bias of the jet-related spectrum hard component which is detected only by means of a highly differential analysis technique based on the TCM. As spectra and ensemble data are presented in Ref. alicenewspec that information is inaccessible.

VII Systematic uncertainties

Estimation of data systematic uncertainties typically addresses the reliability of numerical values resulting from physical measurements. In addition to inevitable statistical fluctuations the reliability of instrument calibrations and resulting data corrections is estimated. That approach is adequate if the interpretation of numerical values is unambiguous. In the present case where data volumes of 60M or 105M events are the basis for analysis systematic errors may dwarf statistical errors, making their correct estimation all that more important.

In this analysis the two-component model, a formal procedure with elements inferred from lower-energy - spectrum data, is used to separate two disjoint contributions to measured 13 TeV - spectra. For the analysis of systematic uncertainties in this study both the accuracy of the separation and physical interpretation of the results are in question. This section addresses the following questions: (a) What is the overall accuracy of the TCM for - spectrum data descriptions? (b) What is the significance and physical interpretation of selection-bias trends relative to the TCM? (c) What is the accuracy and interpretation of spectrum parametrizations related to jets? (d) What is the effect of spherocity as a basis for jet preference and the physical interpretation of results?

VII.1 Overall accuracy of the TCM per Sec. III

Based on Figs. 6 and 8 it might be argued that the TCM shows highly significant deviations from - spectrum data and is therefore a poor model. But the TCM is a predictive reference based on a broad survey of yield, spectrum and correlation data ppprd ; ppquad ; alicetomspec ; anomalous ; ppbpid ; jetspec2 ; fragevo suggesting that the concept of systematic uncertainty should be reconsidered. How should the TCM be required to describe data and how well does it do that? Do significant data-model deviations reveal a faulty model or unexpected information carried by particle data?

In the present study the TCM is applied as a fixed reference to a minimum-bias ensemble of - spectra sorted into multiplicity classes via two methods. The fixed TCM then provides highly differential information on resulting spectrum bias. If the TCM were fitted to individual spectra the bias trends would then be represented by varying fit parameters whose physical interpretation might be difficult. By examining resulting data deviations from a fixed model in relation to statistical errors as in Fig. 8 a likely physical interpretation may be possible that was not intuitively obvious beforehand.

The fixed TCM thus provides a valuable reference that is highly constrained by the requirement to describe - spectra for all energies from 17 GeV to 13 TeV via simple systematic variation of model parameters and agreement with predictions based on jet data as illustrated in App. A. The model parameters that appear in Table 1 are those appearing in Table 2 with the following exceptions: The values for used in the present study are 4.0 and 3.8 respectively for 5 and 13 TeV whereas the values in Table 2 are 3.85 and 3.65. The values for used in the present study are 0.58 and 0.60 respectively for 5 and 13 TeV whereas the values in Table 2 are 0.58 and 0.615. Those changes arise because the 13 TeV spectrum data employed in Ref. alicetomspec were in effect SPD data. In the present study it was decided to favor V0M data with the TCM. The motivation is evident in Fig. 9 (right). The values for estimated in the present study are 0.0145 and 0.0170 whereas the values in Table 2 are 0.013 and 0.015 based on the earlier 13 TeV data with its limited reach (maximum vs 54 for SPD in the later study) and 1M total events vs 60M for the later study. With those changes the TCM provides a good description of V0M data for the six highest classes as demonstrated in Fig. 8. Deviations for lower classes carry important new information about biases as noted.

The TCM may be further parametrized to describe trends of spectrum data in detail as illustrated in App. A. The dependence of 13 TeV SPD spectra can then be described within data uncertainties mainly by accommodating hard-component trends. The soft component exhibits no significant dependence in its shape. Within the TCM context variation of hard-component parameters with may then be physically interpreted in terms of mean jet characteristics altered due to selection bias.

VII.2 Bias trends and “fit” quality per Sec. IV

For the Ref. alicenewspec analysis three issues are important for data interpretation: (a) spectrum normalization for each class, (b) the jet contribution to spectra for each class and (c) selection bias for each class and each event selection method. Without a well-defined reference model it is difficult to distinguish among those issues.

Figure 16 (left) shows Fig. 10 (right) repeated for further consideration. The dashed curves for V0M/TCM and SPD/TCM spectrum ratios are those in Fig. 2 (b) and (d) for event classes II (V0M) and VII (SPD), each with . The data spectrum ratio SPD/V0M (solid) is consistent with the lower panel of Fig. 4 in Ref. alicenewspec . The statistical noise artifact common to V0M and SPD spectra (dashed curves) cancels in ratio as an example of common-mode noise rejection. As noted in Sec. V.2 the SPD/V0M trend is interpreted by Ref. alicenewspec to indicate that the V0M spectrum is “harder” than the SPD spectrum. However, comparison of the corresponding TCM reference spectra (dash-dotted) indicates that most of the deviation from unity is simply due to the difference in charge density for the two event classes.

The data-model comparisons of Fig. 8 illustrate the statistical significance of the data-model deviations. It is useful to compare the “fit” quality of the TCM compared to V0M and SPD data spectra, although the TCM is not fitted to individual spectra. The quality of the data description for a given model can be estimated by the reduced statistic

where are observations, are model predictions and is the number of degrees of freedom – the number of observations less the number of model parameters. In the present context a comparable model quality measure is approximated by the second line based on Z-scores as defined in Eq. (6). Since the TCM is not fitted to individual spectra and the resulting statistic is not compared to a probability distribution the second form is applied.

Figure 16 (right) shows values [second line of Eq. (VII.2)] for each curve in Fig. 8. Note that is ordinarily employed as a measure of goodness of fit but in the present case is a measure of the amount of new information carried by data relative to the TCM reference. The V0M and SPD trends are separately equivalent when comparing 5 TeV and 13 TeV data. Both event selection types happen to approximate power-law trends on .

The vertical dotted line at locates class II of V0M (20.5) and class VII of SPD (19.5) events for 13 TeV. There is a factor 5 difference between values. However, the difference would be much greater if not for the structures in Fig. 16 (left) that are common to all spectra as noted in connection with Fig. 9 (left). Without that noise the higher classes of V0M events are approximately statistically consistent with the TCM.

VII.3 Power-law fits: data vs TCM per Sec. V

This refers to Fig. 5 of Ref. alicenewspec vs Fig. 9 of the present study and the substantial differences in the two results. One result arises from a power-law fit to a limited interval; the other result is obtained with a log-derivative applied to spectrum data over a larger interval. The latter data are averaged over an interval chosen based on differential data in Fig. 9 (left) that directly indicates what interval can be approximated by a power law.

Numerically, the power-law model fits result in variation for V0M from 6.0 down to 5.7 and for SPD from 6.2 down to 4.9 whereas the log-derivative produces a fixed value 5.6 for V0M and variation from 5.7 down to 5.2 for SPD. The fixed log-derivative results for V0M are consistent with data/TCM ratios in Fig. 2 (d): i.e. no significant deviation from the TCM hard-component shape above = 4. The same conclusion can be inferred from Fig. 4 (b). The varying results for SPD are consistent with Eq. (17) for in App. A. Note that plotting estimates of rather than leads to a simple linear trend as in Fig. 17 (left) indicating that the effective high- “width” of the spectrum hard component (i.e. ) increases linearly with SPD yield, an informative result.

It is unfortunate that relatively large artifacts appear in the data as sources of systematic uncertainty, as in Fig. 9 (left). The statistical power of 60 million 13 TeV events is thereby degraded, and in the case of the log-derivative requires rejecting the lowest and highest classes. Nevertheless, the consistency of both V0M and SPD exponent data with their respective smooth trends is indicative of the power of the log-derivative method.

VII.4 Ensemble per Sec. VI

Although Ref. alicenewspec estimates systematic uncertainties for ensemble (quoted as 1-2%) the substantial bias from incomplete acceptance is not discussed. It is stated that “The efficiency correction [to ]…is found to be %”, and “The effect of track cuts on was found to be…of the order of 1%.” The only mention of the low- cutoff is “This [primary particle composition] uncertainty takes into account the extrapolation of the spectra to low ….” It is further stated that “The transverse momentum spectra…are fully corrected…[emphasis added].” As demonstrated in Sec. VI.3 the cutoff bias to is about 0.1 GeV/c corresponding to 10-20% of the data values, compared to ALICE estimated systematic uncertainties as noted above.

Given that the total excursion of uncorrected in Fig. 13 (left) is about 65% of the soft-component value 0.48 GeV/c, interpretation of uncorrected data is problematic. The nominal goal of the ALICE spectrum study is determination of jet contributions to spectra, and data are essential for achieving that goal. But one can contrast Fig. 13 (left), where interpretation of the data is quite uncertain, with Fig. 13 (right) where separation of jet and non-jet contributions is accurately achieved.

Another important uncertainty relating to data interpretation is the consequence of event selection based on spherocity . It is expected that low spherocity will prefer “jetty” events and high spherocity will prefer “isotropic” events. The structure of Fig. 13 (left) obscures how the vs trend relates to jets whereas the corrected structure of Fig. 13 (right) brings clarity. Given that clarification the simplicity of Fig. 15 (left) leads to the correct interpretation of “…within uncertainties the overall shape of the [ vs ] correlation…is not spherocity-dependent.” The correct interpretation is that while jet production varies approximately quadratically with , and jet production for SPD events increases -fold relative to NSD -, spherocity has almost no effect on the jet contribution to spectra,

VIII Discussion

In its introduction Ref. alicenewspec asserts that a spectrum “carries information of the dynamics of soft and hard interactions.” As noted “The aim of [Ref. alicenewspec ] is to investigate the importance of jets in high-multiplicity pp collisions and their contribution to charged-particle production at low .” It is proposed to “disentangle the energy and multiplicity dependence” of spectra.” The TCM has been applied to - spectra over three orders of magnitude of - collision energy, and after fifteen years of development arguably extracts all available information from spectra ppprd ; alicetomspec ; ppbpid . The energy and multiplicity dependences of spectra are indeed factorizable, but the energy dependence requires a large energy interval to identify systematic variations accurately; the interval 5 to 13 TeV is too small to do so alicetomspec ; jetspec2 . Given those observations it is instructive to consider certain comments within Ref. alicenewspec relative to TCM results.

VIII.1 Spectrum evolution with

This topic mainly concerns Figs. 2 and 3 of Ref. alicenewspec which present ratios of spectra for different classes, two energies and two event selection criteria to minimum-bias INEL spectra. It is noted that “the features of the spectra…are qualitatively the same for both energies” and only the 13 TeV result is further discussed. That strategy can be compared with “disentangle the energy and multiplicity dependence.” If two things are “qualitatively the same” then they are quantitatively dissimilar, i.e. the difference is information carried by spectra.

Commenting on Figs. 2 and 3 “The [spectrum] ratios to the INEL distribution exhibit two distinct behavior [sic].” In brief, at lower the spectrum ratios exhibit small dependence, but above 0.5 GeV/c the ratios are strongly dependent on and . Referring to Fig. 2 is the comment “…the spectra become harder as the multiplicity increases, which contributes to the increase of the average transverse momentum with multiplicity.” But the seemingly dramatic spectrum “hardening” in Fig. 2 does not dominate () trends where the central issue is dijet production as a function of described comprehensively via the TCM alicetommpt ; tommpt . The term “hardening” is ambiguous between increased jet number with and possible bias of jet fragment distributions fragevo .

In abstract and main text is the statement “The high- ( GeV/c) yields of charged particles increase faster than the charged-particle multiplicity, while the increase is smaller [i.e. less rapid than ] when we consider lower- particles.” In relation to its Fig. 6 describing charge integrals within specific intervals Ref. alicenewspec observes “Despite the large uncertainties, it is clear the data show a non-linear [i.e. faster than ] increase.” But the TCM has provided an accurate quantitative picture of such trends for fifteen years as noted above. The low- part of spectra ( GeV/c or ) increases , i.e. slower than , whereas the higher- part of spectra (i.e. GeV/c or ) increases precisely , i.e. approximately quadratically with . Again as noted, a characteristic aspect of certain observations in Ref. alicenewspec is confusion among several issues: (a) spectrum normalization (or not), (b) jet production vs , and (c) various selection-bias effects.

VIII.2 Manifestations of jets in spectra

Given a primary goal of Ref. alicenewspec – determination of the jet contribution to particle production at lower – it is difficult to find any responding result in the paper. Regarding spectra in relation to pQCD “…the high- ( GeV/c) particle production is quantitatively well described by perturbative QCD (pQCD) calculations….” But no experimental evidence is presented relating jet contributions at higher , or jet production in general, to hadron production at lower . In contrast, the TCM quantitatively isolates minimum-bias jet contributions to hadron production over the entire acceptance as in Sec. III.3, and spectrum hard components have been quantitatively related to pQCD via measured jet energy spectra and fragmentation functions fragevo ; jetspec2 .

Reference alicenewspec does acknowledge information derived from model fits to spectra: “Commonly, the particle production is characterized by quantities like integrated yields or any fit parameter of the curve extracted from fits to the data, for example, the so-called inverse slope parameter []…” and then emphasizes power-law exponent as relating to jet production. For description of spectra at higher “the natural choice is fitting a power-law function…to the invariant yield [ spectrum?] and studying the multiplicity dependence of the exponent () extracted from the fit.” One conclusion – “the results [the trend] using the two multiplicity estimators [V0M and SPD] are consistent within the overlapping multiplicity interval” – is problematic as argued below.

A mechanism for dependence of exponent is conjectured as follows: “In PYTHIA 8, it has been shown that the number of high- jets increases with event multiplicity.” In fact, the exact multiplicity dependence of jet production in inelastic - collisions is reported in Ref. jetspec2 based on event-wise-reconstructed jet measurements, not a Monte Carlo. The conjecture continues: “…based on PYTHIA 8 studies, the reduction of the power-law exponent [n] with increasing multiplicity [] can be attributed to an increasing number of high- jets.” But for V0M event selection in Fig. 9 (right) the exponent trend on is consistent with a constant (13 TeV) or even slight increase (5 TeV). The same jet population is accessible to either selection criterion and jet number is strictly dependent on as demonstrated by Fig. 12. All that differs is the spectrum bias at high induced by the selection method. Such arguments confuse basic QCD jet production (with its well-established systematics) and manifestations of event selection bias.

The dijet production rate for NSD - collisions can be predicted from measured jet cross sections, and such predictions can be compared quantitatively with jet contributions to spectra and two-particle correlations identified by their unique dependence (e.g. as represented by the TCM) fragevo . For 200 GeV NSD collisions 3% of events include a dijet per unit of eta ppprd . For TeV NSD collisions 15% of events include a dijet per unit of eta jetspec2 , where the quoted percentages are . For a typical range of - charge densities the dijet yield should increase by factor 100 due to the observed trend . 13 TeV - collisions with SPD should include 11 dijets per unit pseudorapidity on average. “Jets” here assumes a minimum-bias jet spectrum wherein most jets appear near 3 GeV (the effective jet spectrum mode).

VIII.3 Selection biases and QCD

The same minimum-bias INEL event ensemble is partitioned into ten multiplicity classes according to two selection criteria – V0M and SPD. The V0M or “forward [on ] multiplicity estimator” is said to “minimize the possible autocorrelations induced by the use of the midpseudorapidity estimator.” The statement suggests that the V0M criterion should produce substantially less bias. “The comparison of results obtained with these [V0M and SPD] estimators allows to understand potential biases from measuring the multiplicity and distributions in overlapping regions.” As with statements about jet contributions to lower it is difficult to find within Ref. alicenewspec any such understanding. In fact “bias” as in that sentence does not appear again in the paper.

For spectrum data plotted as ratios, as in Figs. 1 and 2 (b,d), selection bias from V0M and SPD criteria appear quite different. However, the apparent large high- bias for SPD involves a tiny fraction of all particles and even a small fraction of jet fragments. When the two criteria are compared based on significance as in Fig. 8 the SPD high- bias does not dominate the structure. Ironically, V0M bias is at least as significant as SPD bias and the dependence is similar, contradicting the expectation that “autocorrelations” are minimized by disjoint intervals.

Particle production and QCD dynamics must be strongly correlated between V0M and SPD acceptances. Hadron production at midrapidity depends in part on a parton splitting cascade within each projectile proton that also contributes hadrons at larger . Thus, fluctuations in V0M must be strongly correlated with fluctuations in SPD, albeit SPD has additional contributions from parton scattering and fragmentation to jets. Figure 8 reveals that fluctuations correlated between V0M and SPD are statistically dominant, whereas fluctuations in low-energy jet formation play a less-significant role.

VIII.4 Ensemble vs spherocity

As part of a strategy to identify jet contributions at lower Ref. alicenewspec introduces spherocity (effectively an azimuthal asymmetry measure): “The present paper reports a novel multi-differential analysis aimed at understanding charged-particle production associated to partonic scatterings with large momentum transfer and their possible correlations with soft particle production.” But most of the jet-related hard component arises from lower-energy partons jetspec2 ; fragevo , and most fragments from any jet appear at low eeprd . “Transverse spherocity…has been proven to be a valuable tool to discriminate between jet-like and isotropic events….” That statement is based on material presented in Ref. ortizspher which is a study of various event-shape measures applied to PYTHIA simulations. It is not clear from that study what spherocity contributes to understanding real - collisions.